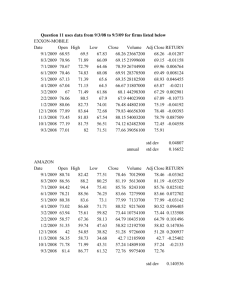

Equity beta - Australian Energy Regulator

advertisement