1 THURSDAY MORNING STUDY GROUP FAITH AND LIFE A Group

advertisement

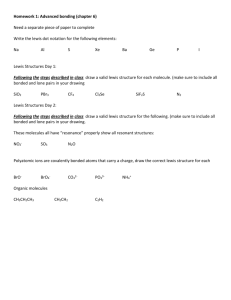

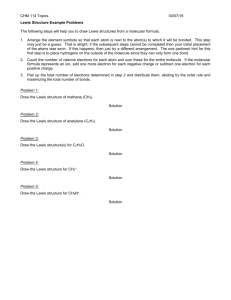

THURSDAY MORNING STUDY GROUP FAITH AND LIFE A Group for In-Depth Learning and Sharing 2014 Section I: Selected Writings of C.S. Lewis Facilitators: John Scruggs / Art Sauer September 4, 2014 Advance reading assignment: Mere Christianity by C.S. Lewis Book 1. Right and Wrong as a Clue to the Meaning of the Universe Chapter 1. The Law of Human Nature Chapter 2. Some Objections Chapter 3. The Reality of the Law Chapter 4. What Lies Behind the Law Chapter 5. We Have Cause to be Uneasy Opening Prayer: Introduction to C.S. Lewis C.S. Lewis is a phenomenon in that, almost fifty years after his death, he remains one of the world’s most popular and best-selling authors. He remains so, not just in one genre but many: children’s literature, science fiction, theology, philosophy, Christian apologetics, autobiography, essays, the novel and poetry. Remarkably all of this output was incidental to his professional career as a highly respected scholar of medieval and Renaissance literature at Oxford and Cambridge. His academic publications are still of considerable importance to students and specialists alike. Lewis’s personal life is part of the phenomenon. Numerous biographies have been written about him. Shadowlands (not authored by Lewis), the story of his late marriage and eventual bereavement, won popular and critical acclaim as a television film, a stage play, a radio-play, and a movie. His most famous children’s book – The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (the first book of the Chronicles of Narnia) – also achieved success as a major motion picture and became one of the top-grossing films of 2005. While Lewis is a phenomenon he is also an anomaly in that, while he has a vast and loyal readership, scholars are sharply divided over the value and significance of his work. This is especially true in theology and religious studies. In evangelical circles Lewis’s reputation is astonishingly high, while many mainstream academic theologians do not consider him a “serious” figure. For example, in 2000 the influential American evangelical magazine Christianity Today put Lewis’s Mere Christianity at the very top of their list as the “best” religious book of the twentieth century. Conversely the comprehensive, multi-author reference work The Modern Theologians: An Introduction to Christian Theology since 1918 published in 2005, viewed by many as an authoritative survey of theological figures and movements during this period, does not even mention Mere Christianity (not even in the chapters on Anglican or 1 evangelical theology). Lewis himself does not even make the index, although he is mentioned once in the text as someone who believed in miracles. Lewis often inspires extreme reactions, both positive and negative, with readers either devoting themselves to him with a passionate and uncritical acceptance that borders on fanatical, or reacting with a loathing and contempt that is scarcely less intense. The positive extreme is largely associated with American evangelicals, and the negative extreme with British atheists. However, his detractors are not all British and those who regard his thought as valuable and interesting can be found across the theological spectrum, including British and North American Anglicans, Roman Catholics and Eastern Orthodox. Accordingly, various schools of Lewis interpretation have developed, each promoting its own version of the man: some more Catholic, some more evangelical, some more conservative, and some more liberal. Lewis is, almost certainly, the most influential religious author of the twentieth century. Whether for good or ill, literally millions of people have had their understanding of Christianity decisively shaped by his writings. Whether one responds positively or negatively, it is Lewis’s vision of the Christian faith that many take as normative and thus either accept or reject. Why has Lewis – a former atheist turned Anglican Christian, a literary scholar without formal theological training or church authority – assumed such a significant role as the interpreter of Christianity for so many? Quite possibly this may have something to do with the way in which Lewis harnessed his imagination, reason, historical knowledge, wit and considerable rhetorical gifts in a sustained effort to communicate the substance of his convictions to as wide an audience as possible. (Excerpted from The Cambridge Companion to C.S. Lewis by Robert MacSwain and Michael Ward) Clive Staples (“Jack”) Lewis: 1898 – 1963 – His Life and Times Clive Staples Lewis was born on November 29, 1898 in Belfast, Ireland and baptized the following year in the Anglican Church of Ireland. His parents – Albert James Lewis and Florence August Hamilton – were well-educated members of the middle class. Their only other child, Lewis’s older brother Warren (1895 – 1973), was to become Lewis’s closest lifelong friend. At a young age, not liking his name, Lewis announced that he was “Jack” and that is what he remained to his family and friends for the rest of his life. Lewis died on November 22, 1963, the day of the John F. Kennedy assassination. Lewis had a happy early childhood, but his mother’s death from cancer a few months before his tenth birthday had a devastating effect on him: not only did he lose his mother, but this also led to a growing emotional estrangement from his father that was never repaired. He was sent away to boarding school in England less than a month after his mother’s death. It was a horrendous experience for Lewis who also hated his subsequent educational experience at Malvern College (1913 – 1914). In 1911 he became an atheist, although on December 6, 1914 he still accepted the Anglican rite of confirmation in the same church where he had been baptized. After leaving Malvern, Lewis was privately tutored by his father’s former headmaster, William Kirkpatrick a well-known and ruthless teacher of logic. Kirkpatrick wrote to Albert Lewis that Clive Staples could aspire to a career as an author but that he had little chance of succeeding at anything else. Lewis entered University College, Oxford on April 29, 1917. With the First World War well underway, almost immediately arriving at Oxford, Lewis joined the British Army. He travelled to France as a second lieutenant in the 3rd Somerset Light Infantry and arrived at the front line on his nineteenth birthday. On April 15, 1918, in the Battle of Arras, he was seriously wounded by an exploding shell and spent the remainder of the war in a British 2 hospital. Lewis’s school friend Paddy Moore was killed during the war. Lewis had committed to look after his mother and his sister should such a fate befall his friend. Mrs. Moore lived with Lewis as his “mother” for many years thereafter. In January, 1919 he returned to Oxford to continue his formal education. By any standard, C.S. Lewis was a brilliant student. He achieved three consecutive First Class qualifications (degrees): the first two in the Oxford “Greats” course – Classical Honour Moderations (1920) and Literae Humaniores (1922) – and the third in English (1923). “Greats” involved the study of Greek and Latin language and literature, philosophy and ancient history, and thus provided a threefold mental training in precision of language, clarification of concepts and the weighting of historical evidence. He never formally studied theology. Lewis’s first position was teaching philosophy at his own college, but this was only a one-year sabbatical-replacement appointment. In 1925, he was elected to a fellowship in English at Magdalen College, Oxford. Lewis’s first love was English literature and it became his area of professional expertise. He tutored at Magdalen and lectured at Oxford for almost thirty years. In January, 1955 he became the Chair of Medieval and Renaissance Literature at the University of Cambridge, where he remained for the rest of his career. Lewis’s turn to atheism in 1911 was not a passing phase of adolescence, but a sincere, thoughtful and intense rejection of religious belief on moral and intellectual grounds. Lewis’s diaries, letters and earliest writings all testify to the consistency and vigor of his atheism. However, as Lewis recounts in his autobiography Surprised by Joy, his atheistic view of the universe was in constant tension with “an unsatisfied desire [joy] which is itself more desirable than any other satisfaction.” This persistent longing, coupled with his friendship with J.R.R. Tolkien, a devout Roman Catholic, cause Lewis in 1929 to become a theist, but only in abstract, impersonal, idealistic terms. It was not until September, 1931 after a long conversation with Tolkien and another friend, Hugo Dyson, about metaphor and myth that Lewis finally accepted Christianity as what he called “a true myth: a myth working on us in the same way as the other, but with this tremendous difference that it really happened.” During World War Two, Lewis became a champion of orthodox Christianity. He saw his mission as a defender of the faith in a spiritual warfare that was raging in contemporary culture. His “war service” was to fight for what he believed to be the essential nature of Christianity. He traveled to Royal Air Force bases in 1940 and 1941 giving lectures on Christianity to servicemen. BBC Radio broadcasts by Lewis in 1941, 1942 and 1943 discussing Christianity and what Christians believe ultimately where compiled into book form in Mere Christianity. Because he is now so strongly associated with American evangelicalism, it is important to stress Lewis’s essentially Anglo-Irish and Anglican character. Culturally and socially, Lewis was very much the product of his middle-class Ulster childhood, Edwardian Britain, the trenches of the First World War, and the Oxford Greats School. In the preface to Mere Christianity, Lewis says: “There is no mystery about my own religious position. I am a very ordinary layman of the Church of England, not especially “high”, nor especially “low”, nor especially anything else.” Although he eventually adopted some “High Church” practices, such as spiritual direction, confession and frequent communion, Lewis was never a member of the Anglo-Catholic wing of the Church of England, nor of the evangelical or any other “wing.” He remained committed to “mere Christianity”, which he found in the broad Anglican via media, with its attempt to fuse the Catholic and Protestant tendencies of Western Christendom, its long tradition of scholarship and literary expression, and its reluctance to define points of controversy among Christians. 3 According to MacSwain and Ward, Lewis, although theologically traditional, doctrinally orthodox and generally conservative in his interpretation of the Bible, nevertheless accepted some form of cosmic and biological evolution, did not hold to the inerrancy of scripture, and was not committed to a specific theory of atonement. Nor, on the other hand, did he accept papal infallibility, Marian dogmas, or the claims to primacy made by the Roman Catholic Church. These issues for him were not essential to mere Christianity. No synopsis of the life of C.S. Lewis would be complete without mentioning that in 1957, Lewis greatly surprised his friends and colleagues by marrying Joy Davidman, a terminally ill, divorced American, with two young sons, who was also an author, a former Marxist atheist, and an ethnically Jewish convert to Christianity, which is the story told in Shadowlands. (MacSwain and Ward) The Journey to Christianity: From Atheist to Defender of the Faith A loss of faith: The brand of Christianity that Lewis experienced in childhood left a bad taste in his mouth for years. Church became synonymous with all things dry and legalistic. Lewis writes in his autobiography Surprised by Joy that “religious experiences did not occur at all” in his upbringing. The death of Lewis’s mother left him deeply disturbed. At the time, he thought of God as a magician who waved his magic wand the moment anyone asked him to do something. As a result, young Lewis was mystified as to why God didn’t answer his prayers to heal his mother. Although this apparent desertion troubled him, Lewis continued to explore his faith while at boarding school. Although Lewis read the Bible, prayed regularly, and discussed issues of faith with other students his faith gradually withered away. The most dramatic change was influenced by a teacher who became fascinated with spiritualism which turned Lewis’s mind to beliefs far different from Christianity. In addition to the normal struggles of adolescence, Lewis became disillusioned as his prayers seemed to go unanswered. He moved further and further away from Christianity and began ultimately considering himself an atheist, abandoning faith altogether. His stated attitude mirrored that of the Roman philosopher Lucretius: “Had God designed the world, it would not be A world so frail and faulty as we see” The vacuum in Lewis’s life was filled with what he called “northernness,” a fascination with Norse mythology and northern lands. Northernness became Lewis’s surrogate religion, a substitute that was everything Christianity was not for him: passionate, meaningful, joy-giving and imaginative. After his conversion, Lewis looked back and said: “Sometimes I can almost think that I was sent back to the false gods there to acquire some capacity for worship against the day when the true God should recall me to Himself.” The impact of Phantastes by George MacDonald: Lewis’s first step toward Christianity came when he first read the fairy tale for adults, Phantastes by the Scottish minister George MacDonald. The book tells the story of a young man who finds himself on a long journey through a land of fantasy. It is the story of a spiritual quest that is at the core of his life’s work and can only end with the ultimate surrender of the self. Phantastes is an allegory about the spiritual world and spiritual things, but Lewis did not fully comprehend this at the time. Nevertheless, Lewis noted after reading the book that he had “crossed a great frontier.” 4 Later he reflected that the book served: “…to convert, even baptize…my imagination. It did nothing to my intellect nor at the time to my conscience. Their turn came far later with the help of many other books and men.” (See Luke 10:27) Despite the impact of MacDonald’s work, Lewis’s logical mind was dead set against Christianity from his boarding school years until his late twenties. He argued that there was no proof of any religion and believed them all to be myths, much like the Norse myths that he loved. In fact, his earliest works, Spirits in Bondage and Dymer were distinctly pessimistic and antagonistic toward God. The impact of The Everlasting Man by G.K. Chesterton (1926): This work of Christian apologetics, written as a bit of a rebuttal to H.G. Wells’, The Outline of History had a further profound impact on Lewis’s journey toward Christianity. “Jesus was a penniless teacher who wandered about the dusty sun-bit country of Judea, living upon casual gifts of food; yet he is always represented clean, combed and sleek, in spotless raiment, erect, and with something motionless about him as though gliding through the air. This alone has made him unreal and incredible to many people who cannot distinguish the core of the story from the ornamental and unwise additions of the unintelligently devout” (From The Outline of History by H.G. Wells) “The critics of course try to create a different Christ from the one portrayed in the Gospels by picking and choosing whatever they want. …But the main impression one gets from studying the teachings of Christ is that he really did not come to teach. What separates Christianity from other religions is that its central figure does not wish to be known merely as a teacher. He makes the greatest claim of all. Mohammed did not claim to be God. Buddha did not claim to be God. But Christ did claim to be God. The story gets stranger still. All of Christ’s life is a steady pursuit towards the ultimate sacrifice - the Crucifixion.” (The Everlasting Man, lecture by Dale Ahlquist, American Chesterton Society) Although gradually coming to believe that the Christian view of the world was logical and reasonable, Lewis continued trying to dismiss it by saying, “Christianity was very sensible apart from its Christianity.” Accepting the reality of a deity (1929): Lewis began to understand that he, like all of us, had a very stark choice before him: he could believe in God or deny him. Ultimately Lewis found it impossible to consciously deny God’s existence. In 1929, Lewis finally admitted that God was God. In Surprised by Joy Lewis calls himself “the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England.” However, Lewis stopped short of believing in Christianity. While he believed in the reality of a deity, he wanted to go no further. He denied the possibility of any relationship with God, saying: “For I thought he projected us as a dramatist projects his characters, and I could no more ‘meet’ Him, than Hamlet could meet Shakespeare. I didn’t call Him God 5 either; I called Him Spirit. One fights for remaining comforts.” Myth becomes truth, accepting Jesus Christ as Lord and Savior (1931): Lewis’s process of becoming a Christian was finally consummated in 1931. During a long evening with friends J.R.R. Tolkien and Hugo Dyson (both Christians) myths were the topic of discussion. Lewis told his colleagues that he loved myths as stories but dismissed them as having any validity. Myths were simply “lies breathed through silver” according to Lewis. Tolkien disagreed, arguing that myths almost always have a grain of truth in them, although the truth is usually skewed or distorted. The difference between Christianity and other myths asserted Tolkien is that Christianity is a particular myth that just happens to be true – God really did come to earth as a man and died so that those who believed in Him could receive salvation. After this long night of conversation Lewis realized that he was ready to accept the truth of Jesus Christ as Lord and Savior. In Surprised by Joy, he describes his feelings: “I was by now too experienced in literary criticism to regard the Gospels as myths. They had not the mythical taste…If ever a myth had become fact, had been incarnated, it would be just like this. Myths were like it in one way. Histories were like it in another. But nothing was simply like it…This is not ‘a religion’ nor ‘a philosophy.’ It is the summing up and actuality of them all.” Later, during a trip with his brother Warner, he set aside all hesitation and doubt, deciding that he believed in Jesus Christ as the Son of God. The decision was far more than an intellectual one for Lewis. It transformed his whole life as he focused much of his future work and writing on defending or articulating the Christian faith. (Wagner) The “Essential” Lewis Books The Chronicles of Narnia (The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe) (1950) The most popular of The Chronicles of Narnia, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe tells the story of four British children who enter an enchanted world called Narnia through a magic wardrobe. Once there, the children discover that the White Witch has cast an evil spell on Narnia, holding it in endless winter. An allegorical tale of Biblical themes. The Screwtape Letters (1942) The Screwtape Letters follows a senior devil named Screwtape as he instructs a junior devil named Wormwood in the art of temptation. Both are in the civil service of Hell, charged with tempting humans. The book is presented as a collection of letters from Screwtape to Wormwood, giving tips and techniques on how Wormwood can derail the Christian faith of a British man living during the height of World War Two. The Great Divorce (1945) The Great Divorce is a dream fantasy that follows a group of ghosts from Hell who board a bus and visit Heaven. The passengers not only discover how different Heaven looks and feels compared to Hell, but they also get to decide whether they want to stay. The narrator of the story is a passenger on the bus, and all the events that take place are seen through his eyes. 6 Mere Christianity Lewis’s best known Christian apologetics book, Mere Christianity, provides a philosophical but approachable defense of Christianity with an explanation of common Christian beliefs. The book originated as a popular series of broadcast talks given by Lewis on BBC radio during World War Two. These talks were originally published as three separate books (The Case for Christianity, Christian Behavior and Beyond Personality), but they were combined into one book as Mere Christianity a decade later. This is Lewis’s best and clearest rational defense of the Christian faith. Tips for Reading Lewis • Understand that his books are written from the perspective of a “Mere Christian.” Lewis attempts to express those beliefs that are common among all Christians. He aims his focus on “mere” Christianity – the core beliefs that Protestant, Catholic and Orthodox Christians could all embrace without disagreement. • Lewis writes as a layman. While described at times as a theologian, he never formally studied theology. • Lewis combines cold, calculating rationalism with the Christian hope of Heaven. He mixes his logic and realism with the promise claimed by Christianity. To Lewis, faith and reason both point towards identical truth. In The Problem of Pain, he writes “We are afraid of the jeer about ‘pie in the sky,’ and of being told that we are trying to ‘escape’ from the duty of making a happy world here and now into dreams of a happy world elsewhere. But either there is a ‘pie in the sky’ or there is not. If there is not, then Christianity is false, for this doctrine is woven into its whole fabric. If there is, then this truth, like any other, must be faced.” • Keep Lewis’s audience in mind. He wrote for the average person in the mid-20th century, not the 21st century. Lewis was greatly impacted by WWI and WWII. The language of his books reflects this influence. • Remember that while Lewis’s works may be great, they are not Scripture. Lewis was brilliant but, like all of us, could be wrong about things. Mere Christianity - Introduction If one wished to write a defense of the Christian faith, there are several approaches he or she could take. Here are some possibilities: • • • • One could present scientific evidence for the existence of God. One might share his or her personal experience with Christ. One might show Old Testament prophecy and its fulfillment in the New Testament. One might describe all the good the Christian faith has accomplished. 7 C.S. Lewis passes over all of these approaches and builds his case on human behavior. The effectiveness of his approach over those described above is significant, for example: • • • • The presentation begins as a discussion of philosophy, not religion. The notion of God is not addressed until well in the discussion. Lewis relies on logical arguments rather than citing religious writings. He eliminates all worldviews except Christianity. Lewis has arranged Mere Christianity so that there is a natural filter at the end of each book, which requires the reader’s buy-in before proceeding to subsequent ideas. • The filter, or hinge for his arguments at the end of Book 1 is: “Christianity only speaks to a person who realizes that there is a Moral Law, there is a Power behind that Law, he has broken the Law and put himself wrong with that Power.” • The filter or hinge for Book 2 (September 11) is that: “Christ was killed for us, that His death washed out our sins, and that by dying He disabled death itself.” This is what Lewis asserts is Christianity; this is what has to be believed according to Lewis for one to be a Christian. This is mere Christianity. Book 1. Right and Wrong as a Clue to the Meaning of the Universe 1. The Law of Human Nature Lewis argues that we can learn something very important from the things people say when they are arguing: • • • • • How would you like it if someone did the same thing to you? That’s my seat, I was there first. Leave him alone, he isn’t doing you any harm. Why should you cut into line ahead of others? Come on, you promised. Lewis asserts that all such talk is appealing to a standard of behavior that one person expects every other person to know about. He then says the standard responses to such statements usually fall into one of two categories: • • The offender argues that his behavior really doesn’t go against the standard. The offender offers excuses as to why his behavior is exempt from the standard. Lewis believes this demonstrates a very important notion. When people are involved in disputes: • • • • They act like a law or rule of morality is in force. They both are agreed on what is right and wrong. They try to demonstrate that the other is in the wrong. And very importantly, without some agreement on what is right and wrong, there is no sense arguing. 8 This Law or Rule about Right and Wrong has various names: • • • • The Law or Rule of Fair Play The Law of Decent Behavior (Morality) The Law of Nature The Law of Human Nature All individuals are governed by certain laws, with one important distinction: • • Individuals are absolutely bound by physical laws, e.g. gravity Individuals can choose to obey or disobey the Law of (Human) Nature The Law of (Human) Nature was called this because: • • • People thought that everyone knew it and did not need to be taught it. People thought that it was obvious to everyone. Different civilizations in different ages have similar ideas of right and wrong. Whenever individuals or nations say they don’t subscribe to the Law of Nature, they betray their core beliefs by appealing to “fairness” in matters in conduct. (Nazis, terrorists) Thus, Lewis concludes that we are forced to believe in a real Right and Wrong. • • Some people may sometimes be mistaken about the specifics. The Law of Human Nature is not a matter of taste and opinion. Lewis summarizes this chapter by making two points: • • There is a Law of Human Nature or Right and Wrong. (Moral Law) None of us is keeping the law of Human Nature In The Abolition of Man, Lewis presents a compelling argument that until modern times, all peoples regardless of culture or geography believed there were good and bad – appropriate and inappropriate – ways to respond to life. What’s more, all these cultures agreed quite closely on what’s right and what’s not. Lewis isn’t just talking about Christianity or Judaism. Instead, he documents the common ethical code that existed across Greek, Roman, Babylonian, Chinese, Sanskrit, Christian, Jewish, American Indian and Australian aboriginal beliefs. Lewis’s chapter summary makes two important points (1) that humans all over the earth think they ought to behave in a certain way, and (2) that none of them believe they behave that way. Lewis then says, “These two facts are the foundation of all clear thinking about ourselves and the universe we live in.” 2. Some Objections In Chapter 2. Lewis addresses some of the objections to the innate nature of the Moral Law / Law of Human Nature. 9 Herd Instinct: Lewis notes that some people believe the Moral Law is simply our herd instinct and is developed like all of our other instincts. According to Lewis there are several arguments why this can’t be true: • There is a difference between being prompted by instinct and being prompted by the Moral Law. o Being prompted by instinct means having a strong urge to act in a certain way. o Being prompted by the Moral Law involves feeling that one ought to act in a certain way. o The thing which judges between two instincts cannot be either one of them. • When we are most conscious of the Moral Law it usually seems to be telling us to side with the weaker impulse. (help rather than flee). We cannot be acting from instinct when we make an instinct stronger than it is. • There are no impulses which the Moral Law may not sometimes tell us to suppress (patriotism, mother’s love) Lewis argues that the most dangerous thing one can do is to take any one impulse of your own nature and set it up as the thing you ought to follow at all costs. Social Convention: Some people argue that the Moral Law is just a social convention, something that is put into us by education. Lewis argues this can’t be true because: • Some of the things we learn are indeed social custom, like driving on the right side of the road. Some are real truths, like physical laws and mathematical principles. • Moral Law is real truth because: o The moral ideas of one time or one country are very similar to those of other times or countries. o We can judge between the morality of one people or country and another. If no set of moral ideas were truer or better than any other, we would be indifferent between differing ideas of morality. • The standard that measures two things is something different from either. Whenever we begin to compare two different moral ideas, we admit that there is a Real Morality, independent of what people think. • If the Rule of Decent Behavior (Law of Human Nature) meant simply “whatever each nation happens to approve,” there would be no sense in saying that any one nation had been more correct in its approval than any other. To put this concept in popular terms, Lewis is here rebutting the notion of “to each his own.” He argues that concepts of right and wrong cannot be matters of personal taste or opinion. Doing so makes those who feel it is okay to cut in line, break promises, etc. hold opinions and views about doing so that are just as valid as yours. However, if your ideas about what’s true and right are closer to the truth than their ideas, then Lewis argues that there must be some Real 10 Morality for them to be true about. He sums up this concept by looking at it in terms of World War Two and Nazi behavior: “What was the sense in saying that they Nazis were in the wrong unless Right is a real thing which they at bottom knew as well as we did and ought to have practiced? If they had had no notion of what we mean by right, then, though we might still have had to fight them, we could no more have blamed them for that than for the color of their hair.” 3. The Reality of the Law Two points from the Chapter 1 are worth reviewing at this point: • • People are cognizant of the idea of a sort of behavior that they ought to practice. This Law of Human Nature goes by several names including the law of fair play, decency or morality. No one is completely and fully keeping this Law of Human Nature (See Romans 3:23) Lewis then poses the question, what does it mean to break this Law: • • Some might say that breaking the Law only means that people are not perfect. True, but not particularly helpful. What are the consequences of something being imperfect, of its not being what it ought to be? Lewis argues the answer depends on the “something” we are thinking about: • If we are speaking of stones or trees, they are what they are, and it is senseless to say that they ought to have been otherwise. The laws of nature applied to stones and trees only means what nature does. These results are facts strictly governed by physical laws. • However, the Law of Human Nature applied to humans does not mean “what human beings do,” but what they ought to do and do not do. And when we are dealing with humans something else is in play beyond the actual facts. So in the case of humans, Lewis argues, we have the facts (how men and women do behave) and we have something else (how they ought to behave). Lewis then ponders the nature of behavior and what makes behavior good or bad, using the example of losing a seat on a train – one because somebody was there first versus somebody who budged in. • Sometimes the behavior we call bad is not inconvenient to us – it does not necessarily harm us. So we cannot say the behavior we call decent is only that which is truly useful to us. 11 • As for decent behavior in ourselves, it should be obvious, according to Lewis, that we’re not talking about behavior that pays. For example: o Being honest on our taxes when it would be easy to cut corners. o Staying in a dangerous place because we have a duty to do so Some people say that though decent conduct does not mean what pays each particular person at a particular moment, it means what pays the human race as a whole. • • Humans know that you cannot have any real safety or happiness except in a society where everybody plays fair. Because most people understand this, they try to behave decently. Lewis believes this notion really misses the point and is circular reasoning. He concludes by asserting that men and women ought to be unselfish and ought to be fair, period. The Law of Human Nature can then be said to have these characteristics: • • • • It is not simply a fact about human behavior, there is a different kind of reality. It is not a mere fancy – we can’t get rid of the idea. It is not how we would like others to behave for our own convenience. It is a real thing, not something we invented, that is pressing in on us. 4. What Lies Behind the Law How did the universe come to be? Lewis notes that since the beginning of the human race, men have puzzled over what the universe really is and how it came to be there. Lewis asserts two views have been held: • The Materialistic View o Matter and space just happen to exist, and have always existed. No one is sure why. o Matter behaves in certain fixed ways, why this happened is unknown, but is very fortuitous for humans. o Our solar system is another fortuitous happenstance. o Some of the matter on planet Earth came to life. o The living creatures on Earth ultimately developed into humans. • The Religious View o What is behind the universe is more like a mind than it is like anything we know. o It made the universe partly for purposes we don’t know, but partly to produce creatures like itself – with the ability to reason. Lewis asserts that one cannot discover which of the two views concerning what the universe is and how it came to be by science in the ordinary sense. • Science fundamentally works by experiments – by observing how things behave and then by making inferences based upon the observations. 12 • Science cannot answer questions concerning why anything exists at all and whether there is anything behind the things science observes. • If there is “Something Behind,” then it will have to remain altogether unknown to man or else make itself known in a different way. • The statement that “there is any such thing” and the statement that “there is no such thing,” are neither of them statements that science can make. Lewis asserts that there is one thing, and only one thing, in the whole universe which we know more about than we could learn from observation. That one thing is Man. He again asserts that what we know about man is: • • • Men [and women] find themselves under a moral law. Men [and women] did not fabricate the law and they can’t forget it. Men [and women] know they ought to obey this law. So the real question according to Lewis is whether the universe simply happens to be the way it is for no reason or whether there is a power behind it that makes it what it is. That power, if it exists, would not be one of the observed facts but a reality which makes them; no mere observation of facts can reveal it. • • Thus, if there was a controlling power outside the universe, it could not show itself to us as one of the facts inside the universe. The only way in which we could expect it to show itself would be inside ourselves as an influence to get us to behave in a certain way. Lewis uses the illustration of a postman delivering letters to prove his point. He writes that the only letter we are allowed to open is Man (ourselves). When we do, especially that particular person called Myself, we discover (1) that I do not exist on my own, (2) that I am under a law, and (3) somebody or something wants me to behave in a certain way. Lewis warns the reader that he is not within a hundred miles of the God of Christian theology. All we have so far is: • • • Something like a mind is directing the universe – it couldn’t be matter because matter doesn’t give direction. This Something appears in us as a law urging us to do right and making us feel responsible when we do wrong. The fact that we have something in us urging us to “do the right thing” is evidence that the second view of how the universe came to be is correct. (See Romans 1:19-20) 5. We Have Cause to Be Uneasy 13 From the previous chapter Lewis concludes that the existence of the Moral Law would lead us to conclude that somebody or something from beyond the material universe was actually getting at us. Lewis suggests our reaction to this might be twofold: • • Some might feel a certain annoyance. They might rather be left to themselves to do what they “jolly well want.” Others might feel that Lewis had pulled a bait and switch – he started talking about philosophy but then switched to religion. Lewis responds to those who think he has shifted from philosophy to religion by asserting: • Some say, “The world has tried religion and it didn’t work, you cannot turn the clock back.” Lewis argues that when you look at the present [1943] state of the world, it is pretty plain that humanity has made a big mistake. Turning the clock back is a sensible thing to do when one discovers he or she has made a wrong turn. o o o o • We all want progress; especially in the sense of morality, or fairness or decency. Progress means getting nearer to place where we want to be – a return to civility. If one is on the wrong road, progress means turning around and going back to the right road. The one who turns back soonest is the most progressive. There is nothing progressive about being pig-headed and refusing to admit a mistake. Lewis argues that several attributes of his discussion confirm he is still talking philosophy not religion: o o o He has not even gotten to the God of any actual religion and certainly not the God of Christianity. The only conclusion reached is that there is a Somebody or Something behind the Moral Law. Nothing has been argued from the Bible or Churches, we are just trying to see how much we can find out about this somebody on our own. So far Lewis has presented two bits of evidence about the Somebody: • The universe He has made. If this were our only clue, we would have to conclude: o o • That He is a great artist – for the universe is a very beautiful place. That He is quite merciless and no friend Man – for the universe is a very dangerous and terrifying place. The Moral Law which He put in our mind. This is more instructive than the universe. We can conclude from this evidence: o o o That He is intensely interested in right conduct – in fair play, unselfishness, courage, good faith, honesty, and truthfulness. That He is not ‘good’ in the sense of being indulgent, or soft, or sympathetic. There is nothing soft about the Moral Law, it is hard as nails. We have not got so far as a personal God – only as far as a power behind the Moral Law, and more like a mind than anything else. 14 From this evidence, Lewis says we can begin to make some inferences about the Somebody or Something: • If it is a pure impersonal mind, there is no use in asking It to make allowances for us or to let us off for our shortcomings. • If it is an impersonal absolute goodness, it would be foolish to conclude that you do not like Him and therefore were not going to bother with Him. • Here then is the dilemma in which we find ourselves: • o On the one hand we are on His side and really agree with His disapproval of human greed and trickery and exploitation. We know that unless the power behind the world really and unalterably detests that sort of behavior, then He cannot really be good. If the universe is not ruled by an absolute goodness, then all of our efforts are hopeless. o On the other hand, we know that if there does exist an absolute goodness, it must hate much of what we do. And if so, we are making ourselves enemies to that goodness every day so our case is hopeless again. He is our only possible ally, and we have made ourselves His enemies. Goodness is either the great safety or the great danger – according to the way one reacts to it. We have reacted the wrong way. In order to move philosophy to something that will really help with the problem Lewis has laid out, several admissions must be made: • Christianity does not make sense until one has faced the sort of facts Lewis has been addressing. • Christianity tells us to repent and promises forgiveness. It has no appeal to people who do not know they have done anything to repent of and who not feel they need forgiveness. • Christianity only speaks to a person who realizes that there is a Moral Law, there is a Power behind the Law, he has broken the Law and put himself wrong with that Power. (This is the first filter in the book as discussed in the Introduction.) • Christianity offers explanations to our dilemma. It explains how God Himself becomes a man to meet the demands of this law, which we cannot meet. • Christianity in the end is a thing of unspeakable comfort.* Discussion Questions 1. In Mere Christianity, Lewis attempts to describe a bare-bones Christianity without getting into the theological differences between denominations. Does this approach help or hinder you in your search for understanding of Christianity? 15 2. Lewis uses a “First Cause” argument similar to that of St. Augustine to argue for the existence of a supernatural force that existed prior to creation. After establishing that such a force exists, he uses it to develop the concept of God. Does this argument convince you or do you need additional proof? 3. Lewis says that “Christianity tells people to repent and promises them forgiveness.” Is this an appealing argument to you? Are there people that would not be affected by this because they feel no reason to repent? *Source material used throughout this document: Mere Christianity by C.S. Lewis The Cambridge Companion to C.S. Lewis edited by Robert MacSwain and Michael Ward C.S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity Shepherd’s Notes, Holman Reference Mere Christianity: Discussion and Study Guide by Joseph McRae Mellichamp C.S. Lewis and Narnia for Dummies by Richard Wagner 16