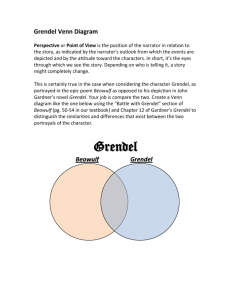

Grendel

advertisement