Mechanisms of Competitive Exclusion Between Two

advertisement

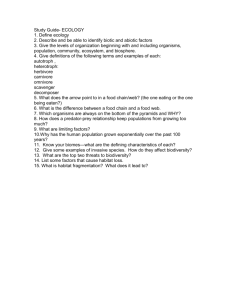

Mechanisms of Competitive Exclusion Between Two Species of Chipmunks Author(s): James H. Brown Source: Ecology, Vol. 52, No. 2 (Mar., 1971), pp. 305-311 Published by: Ecological Society of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1934589 . Accessed: 20/06/2011 15:16 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=esa. . Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. Ecological Society of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Ecology. http://www.jstor.org MECHANISMS EXCLUSION OF COMPETITIVE TWO SPECIES OF CHIPMUNKS' JAMES BETWEEN H. BROWN Department of Zoology, Universityof California, Los Angeles 90024 Abstract. Two species of chipmunks,Eutamias dorsalis and E. umbrinus exclude each other fromcertainelevationson isolatedmountainrangesin the centralGreat Basin. Competitive success is determinedby habitat;dorsalisexcludes umbrinusfromthe sparse pinion-juniper forestsat lower elevationsand umbrinusexcludesdorsalisfromthe denserforestsat higher habitat. altitudes.The two speciesoccur togetheronly in a verynarrowstripof intermediate of the two specieswithinthis overlap zone reObservationof the behaviorand interactions sultedin the followingexplanationfor the mutualexclusion.E. dorsalis,the more aggressive species,chases umbrinusfromthoseareas wherethe treesare so widely and more terrestrial shifts advantageimmediately spaced thatumbrinusmustfleeon the ground.The competitive large and dense that to the more social and arborealumbrinuswhenthe treesare sufficiently In thesehabitatsumbrinusreadilyescapes dorsalisby fleeingthrough theirbranchesinterlock. thetreesover routesthatthe moreaggressivespeciescannotfollow.In such situationsthe agdisadvantageousbecause the more gressivenatureof dorsalisactuallybecomescompetitively social umbrinusis so numerousthatdorsaliswastesa greatdeal of timeand energyon fruitbetweenthe two speciesin aggressivebehaviorapparentlyrepreless chases. The differences sent adaptationsto the densityof cover and food resourcesin their habitats.The main aggresinteraction betweenthesetwo chipmunks(interspecific mechanismsof the competitive sion, the abilityof the subordinatespecies to utilize some featureof the habitatto escape fromthe dominantspecies,and aggressiveneglecton the part of the dominantspecies) may exclusionbetweenhighlymobile animals. in cases of competitive be important frequently Competitiveexclusion has been documented both in the laboratory (Gause 1934, Park 1962, and others) and in the field (Connell 1961, Beauchamp and Ullyott 1932, Hairston 1951, Tanner 1952, Istock 1967, and others). However most of the cases of competitiveexclusion in nature are based upon circumstantial,distributionalevidence, and only Connell (1961) has done extensive experimentalwork in the field and described mechanismsby which exclusion is effected.In his study of the interactions between two species of sessile, intertidalbarnacles, Connell showed that the distributionof one species was limitedto the uppermostregion of the intertidal zone because below that region it was physically crowded out of the limited available space by a second species. This is of particular interestbecause many of the observed cases of competitiveexclusion in nature occur between species of highly mobile vertebrateswhere the mechanismsof exclusion must be very different. The present paper describes the interactionsbetween two species of chipmunks (Eutamias dorsalis and E. umbrinus) which exclude each other from certainaltitudinalranges on numerousisolated mountain peaks in the central Great Basin. Hall (1946) provided excellent distributionalevidence indicating that competitiveexclusion occurred between the two species. The present study was designed to answer the question: How do the species utilize theirhabitats and interactso as to exclude each otherfromall areas but a narrow zone of overlap? 1-Received June1, 1970; acceptedAugust5, 1970. METHODS This study occupied most of two summers, 1968 and 1969. The firstsummerwas spent visitingmany of the mountainrangesin centraland easternNevada where one or both species of chipmunkwere known to occur, in order to confirmHall's (1946) distributional data and become familiarwith the general distributionand ecology of the species. Three weeks (August 5 to 26) of 1968 and most of the summer (July 2 to August 7 and August 21 to September9) of 1969 were spent in the Snake Range where a study area was established on Baker Creek, elevation 2,300 m, 7 miles west of Baker, White Pine County, Nevada. At this study area the microdistribution,habitat utilization,and interspecificinteractions of the chipmunkswere investigatedin detail as describedbelow. Microdistribution.-An area of approximately 1 mile2 (2.6 kM2) which included portions inhabited by each species was censused regularly both summers.All parts of the area were covered at least twice each summer and those places where the ranges of the two species abutted or overlapped were observed much more intensively. Censuses were made by slowly walking through selected areas in the early morning and plotting on a map the location and species of each chipmunkobserved. Interspecific aggression.-Although both species were abundant in the studyarea both summers,indimobile and dispersed that viduals were sufficiently it was impossible to observe a significantnumber of interspecificinteractions among animals in com- JAMES H. BROWN 306 pletely natural circumstances.It was found that an artificialfeedingstation,baited with crushedpeanuts, attracted individuals of both species when it was placed in an area where their altitudinaland habitat ranges overlapped. The feeding station made it possible to observe numerous interspecific -and intraspecificinteractionsbetween chipmunksand to compare the behavior of the two species in identical surroundings.The feeding stationwas maintained from August 9 to 20, 1968, and from July4 to August 7 and August 23 to September 1, 1969. During these periods observations were made 6 days per week from sunrise,when the chipmunksfirstbecame active, until about 0930 hr, when activity began to wane. Occasionally observationswere also made in the late afternoon,but activitywas much less than in the morning and they were not very profitable. The chipmunks rapidly habituated to the presence of the observer,who recorded each visit and aggressive encounter. In 1969 the individuals visitingthe station were trapped, marked with colored plastic discs rivetedthrougheach ear, and released. With the chipmunks individually marked it was possible to determine the total number of individuals visiting the station,the frequencyof visitsby each individual, and the fate of individualsinvolved in aggressiveinteractions. Habitat utilization.-It was obvious that the two species differedin the extent to which they were arboreal or terrestrial.Two methods were used to quantifythe nature of this difference.First, on four differentdays the frequencywith which individuals of each species used the various routes by which the chipmunks approached the feeding station were recorded. Secondly, the amount of time spent in trees or on the ground by individualsof each species was recorded on 8 differentmornings.These latter observationswere made on undisturbedchipmunks at least 300 m fromthe feedingstation. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION General ecology and distribution.-Eutamias dorsalis and E. umbrinus are similar in size (body weights are 55-68 and 51-80 g respectively) and general body proportions.As chipmunksgo, they are quite different in coloration (dorsalis is pale, umbrinus brightlystriped) so thattheycan be distinguished at a distance by an experienced observer. Both species feed mainly on the seeds and fruitsof a variety of plants includingpifion(Pinus monophyla), juniper (Juniperusosteosperma), mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus montanus), wild rose (Rosa sp.), prickly pear (Opuntia sp.), and several grasses and forbs. In addition,umbrinuswere observedfeedingon fungi and the seeds and fruitof chokecherry(Prunus virginiana) while dorsaliswere seen feedingon the seeds of cliffrose (Cowania mexicana). Both species pre- Ecology, Vol. 52, No. 2 fer somewhat open, rocky habitats.Both live in burrows which they dig among rocks or at the base of trees. Both umbrinusand dorsalis are widely distributed United States in the forestedareas of the southwestern in general and on the isolated mountainranges of the central Great Basin in particular. On most of the mountains of eastern and central Nevada (see Hall 1946 for details) both species are present and the forestedhabitatsare partitionedaltitudinallybetween them. E. dorsalis is restrictedto the sparse pifionjuniper associations on the lower slopes. At higher elevations it is replaced by umbrinuswhich ranges up to treeline. There are two mountainranges where only one of the two species occurs. E. dorsalis inhabitsthe Pilot Range and umbrinusis foundin the Ruby Mountains. Both of thesemountainrangesare found at the northern edge of the geographical distributionsof both species and the absence of one may be attributedto historical accident. Each of these mountain ranges has large areas of habitat that is apparentlysuitable for the missing species, but in its absence the other species has expanded its altitudinalrange to include all forested habitats from the lowest pinons and junipersto treeline(Hall 1946; confirmedin the present study). This observationthat each species occupies a wider range of habitats in the absence of the other than it does where both species occur together is excellent circumstantialevidence that their distributions are limited by competitive exclusion when both species inhabitthe same mountain. No direct attemptwas made to determinethe resource for which the chipmunksare ultimatelycompeting,but two observationssuggest that it is food. First,the animals dig theirown burrowsand suitable sites appear to be so numerous that it is hard to imagine that shelter could be a limiting resource. Secondly,individualsof both species engage in rigorous conteststo obtain access to local concentrations of food. This is particularlyobvious in summer and early fall when seeds and fruitsare ripeningand the chipmunks are storing them away for the winter. The bait put out at the feeding station not only attractednumbers of both species to feed, but it also apparentlyinduced several umbrinusto establishpermanentresidencein the immediatevicinity.It should be noted that similarconcentrationsand interactions of chipmunksoccur at natural concentrationsof food as well as at the artificialfeedingstation.I have observed up to fiveumbrinusand two dorsalis (on differentoccasions) feedingin and under a singlepifion with an exceptionallyheavy crop of cones. The preceding observation counters the possible objection that the behavioral interactionsof chipmunksat the feedingstationreportedhere were the aberrantresults of totallyunnaturalconcentrationsof individuals. EarlySpring1971 COMPETITION IN CHIPMUNKS .~~~~~~~~~5 -0 '4+-+ '4 .'',',','',+ Ap.;~~~~ *.':.: C''' 307 Ai 4~~~~-- KEY; 0 E. umbrinus + E dorsalis L and junipers widely spaced Pilons Dirt roads FIG. 1969. - j Streams 1W Dense thickets of aspen, chokecherry, rose No trees or shrubs (meadows or bare ground) --- Contourlines * El! Pinionsand junipers, g branchesfrequently interlocking Rocky cliffs Feeding station -.20 kmI of the two speciesof chipmunkson the studyarea duringJulyand August 1. The microdistributions Microdistribution.-The location of sightings of individualchipmunkson the studyarea in the Snake Range during 1969 are shown in Figure 1. In 1968 the patternwas essentiallyidentical,and it is possible to tell fromfieldnotes and specimensin the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (University of California, Berkeley) that the distributionsof the two species have not changed significantly since fieldparties visited the Baker Creek area 40 years ago. The distributions of the species are largely nonoverlapping. JAMES H. BROWN 308 \+ \ Ala ~~~OBSERVAIOPOSX Ecolo-rvVol. 52,No. 2 + FIG. 2. Detail of the habitatin the vicinity of the feedingstationwhereboth speciesof chipmunksoccur. Hatched areas indicatebare, rockyground;unhatchedareas, soil and littersubstrate.Large irregularoutlines indicatethe canopyspreadof the followingtrees:pifon,circlewithcross;juniper,unshadedcircle;mountain mahogany,shaded circle. measuring more than 100 m in greatestdimension, the zone of overlap is narrow relative to the move* E. dorsalis mentsof the chipmunksthemselves. 20 The small degree of distributionaloverlap and its temporal stabilitysuggeststhat the shiftin competitive advantage fromone species to the othermust be .-J dependent upon some relativelypermanent feature o of their environment.It is apparent from Figure 1 that the distributionsare conspicuously correlated Q~10 withthe densityand size of trees.The transitionfrom one species to the other does not correspond to an 5 ecotone betweenplant communities,but occurs within the pifion-juniper association. E. dorsalis is restrictedto the stands of pifion0-10 40-20 20-30 30-40 40-50 50-60 60-70 80-90 90-100 juniper where the trees are small and spaced so that PER CENT OF TIME ON GROUND there is considerable open ground between them. FIG. 3. Frequencydistribution of the amountof time When the pifions and junipers become sufficiently spenton the ground,as opposedto in trees,by each spe- dense that some of theirbranches interlock,dorsalis cies. The difference betweenspeciesis highlysignificant is replaced by umbrinus. An area of intermediate (P < 0.001). habitat,where both species occur, is mapped in deOnly in a narrow zone, varyingin width from a few tail in Figure 2. It consistsof interdigitating areas of meters to about 200 m, can both species be found. open, rocky ground and stands of pi-nonand juniper Since these chipmunksfrequentlyhave home ranges with interlockingbranches. E. umbrinusalso inhabits 25 - EDE. '1 umbrinus EarlySpring1971 \+\X COMPETITION IN CHIPMUNKS OBSERVATIO POST 309 + FIG. 4. Paths utilizedby each speciesas it approachedthe bait station.Pathsof umbrinus are indicatedby completeshading,thoseof dorsalisby cross banding.Othersymbolsare explainedin Figure2. other dense stands of trees including aspen groves, chokecherrythickets,and, at higher elevations, forests of mixed conifers. Several otherpairs of vertebratespecies have strikingly similar distributionson the mountains of the Great Basin, and this may reflecta similar effectof vegetation structureand competitiveinteractionon these species. They include desert and bushy-tailed woodrats (Neotoma lepida and N. cinerea), Scrub and Steller's Jays (Alphelecoma coerulescens and Cyanositta stelleri), and Plain Titmouse and Mountain Chickadee (Parus inornatus and P. gambelli). The microdistributionsof the last-mentionedpair correspond almost exactly to the local distributions of E. dorsalis and E. umbrinus respectively.This correspondence is maintained despite the much greater mobility of the birds and I have watched flocks of titmice fly over or around vegetation of inappropriatedensitywithoutstoppingto forage. Effects of vegetationstructureon interspecificinteractions are apparentlyof quite general occurrence, at least in vertebrates. Rosenzweig and Winakur (1969) have recently found habitat structureto have an importanteffect of desert rodents and Cody on the microdistribution (1968) has analyzed its influenceon the competitive relationshipsbetween species of birds in grasslands. Habitat utilization.-Despite the fact thatboth species harvestmuch of theirfood in trees,umbrinusis much more arborealthan dorsalis. It spends a greater proportionof its time in trees than dorsalis (Fig. 3) and when approaching the feeding station it tended to dash out from a nearby clump of trees whereas dorsalis usually approached on open, rocky ground (Fig. 4). This verysignificantdifferencein the ability of the two species to utilize trees is also apparent from the following qualitative observations. When approached by man, or a predator,dorsalis usually runs away on the grounduntilout of sight,and when disturbedit will often descend from a tree and flee in this manner. On the other hand, umbrinususually climbsthe nearestgood-sizedtree and "freezes"when it is disturbed. In interspecificaggressiveencounters an umbrinusfrequentlyescaped froma pursuingdorsalis by climbinga tree and eitherrunningout to the tip of a long, thin branch or crossingto anothertree throughthe branchesand the dorsalisfailed to follow. Interspecificaggression.-The feedingstationswere highlysuccessfulat attractingmembers of both species and a large number of interspecificand intra- Ecology,Vol. 52,No. 2 JAMES H. BROWN 310 TABLE at the feedingstationin 1969 1. Visitsand aggressiveinteractions Aggressiveencounters Visits ummb Total number............... .... ..... Observedfrequencyb Expected frequencyb Number of individuals....... dor umb > umb 1,162 946 143 551 .449 18 11 .203 .304 13 dor> umba umb> dora 310 83 dor > dor 166 .237 .201 9 .560 .495 21 theloseris thespeciesontheright. is thespeciesontheleftofthe> symbol, aThewinner andare calculated tospeciesidentity, withrespect wererandom amongindividuals ifencounters arethoseexpected encounters ofaggressive frequencies bTheexpected is highly ofencounters significant ofvisitsbybinomial frequencies andexpected between observed theobserved expansion.Thedifference (X2 = \33.2; from frequency P< .005). specific behavioral interactionswere observed. The resultsof the observationsat the feedingstationduring 1969 are summarizedin Table 1. As soon as the 9 O---O=E.umbrinus __ o chipmunkswere coming to the station regularly,an Z 8 dorsaIis -=E. interspecificdominance heirarchywas rapidly estab57 lished; higher ranking individuals chased away and ?5 defended the feeding area against subordinate an6~~~~~~~~imals. E. dorsalis was significantlymore aggressive than umbrinus.Individuals of dorsalis occupied the / four highest positions in the dominance hierarchy, 3 of all interspecificencounters, and won four-fifths engaged in more interspecificand intraspecificinterI l l j~~~~~~~~~~~~ Io actions than predictedon the basis of the number of 10 30 5 20 25 15 10 -AUGUST JULYEvisits of each species. Qualitativelyit was apparent of each speFIG. 5. Numbersof individualchipmunks that individualsof dorsalis invariablyapproached the feeding station alone whereas those of umbrinus cies visitingthe feedingstationduringa 5-weekperiod in 1969. frequentlytraveledin pairs made up of varyingcombinationsof ages, sexes, and individuals. The aggressivenature of dorsalis is apparentlyan in injuryto the umbrinusbecause they immediately adaptation to its sparsely vegetated habitat, where fled to nearby trees and evaded the pursuingdorsalis selectionfavors those chipmunksthat are sufficiently as describedin the previous section. The data presented in Figure 5 suggest that the aggressive to defend the scarce, widely distributed food sources against nonspecificand heterospecific continuedutilizationof the bait by large numbersof competitors.Where the local distributionsof the two umbrinusled to the abandonmentof the station by species overlap, umbrinus is more numerous and several dorsalis. Certainly the number of dorsalis more tolerantof other chipmunksthan dorsalis. This visitingthe stationdeclined and this decline was not probably reflectsnot only reduced selection for the owing to mortalitybecause two marked dorsalis freaggressivedefense of a large area, but also selection quentlywere seen in the general area, but many yards for some sort of loose social association because of fromthe station,aftertheir last visit. The following the advantage of having additional animals nearbyto sequence of interspecificinteractions,frequentlyobdetect and give warningof concealed predators.Cer- served once more than five or six umbrinus were tainly the opportunitiesfor a predator to approach visitingthe bait, probably accounts for the decline in unobservedare much greaterin the denselyvegetated the number of dorsalis in the immediate vicinityof the station.A dorsalis would chase an umbrinusfrom habitats. Between July 4 and August 7, 1969, the longest the bait into a nearby tree and returnto the station period that the feeding station was in continuous only to find it occupied by another umbrinusbusily operation,therewere interestingchanges in the num- feeding or filling its cheek pouches. The dorsalis ber of individualsof each species that were using the would banish the second umbrinus to a tree, but bait (Fig. 5). Although dorsalis began to visit the meanwhile the firstumbrinuswould have slipped in bait first,new individualsof umbrinuswere attracted again to feed, and so the process would continue. untiltheywere twice as numerousas dorsalis. Addi- Often the dorsalis would eventuallyleave the station tional umbrinuswere recruitedto the station despite withouthaving fed. In such cases the aggressivenarepeated aggressive encounters (which they usually ture of dorsalis obviouslyworked to its disadvantage. and competitivelydisadvantageous lost) withdorsalis. These encountersseldom resulted Similar inefficient v I t Early Spring 1971 COMPETITION IN CHIPMUNKS 311 effectsof self-defeating effectsof interspecificaggressionhave been described Miller 1967). The inefficient, in several species of birds (Ripley 1961) and termed interspecificaggression in some circumstanceshave been observed in several bird species (Ripley 1961). aggressiveneglect. Differencesin abilityto locomote and take refugein CONCLUSIONS certain portions of the habitat such as trees or tall I conclude that mutual competitiveexclusion be- buildings,in addition to differencesin aggressiveness, tween the two species of chipmunksis effectedin the are an importantpart of the interaction between followingmanner.E. dorsalis is more aggressivethan Norway and roof rats (Ecke 1954). It certainlyseems E. umbrinus and is better at moving over open that interspecificaggressionwhich seldom results in widelyspaced that mortalityor even injury is a common element in ground.When treesare sufficiently its competitormust flee significantdistances on the many cases of competitiveexclusion between highly defendslocalized resources mobile animals. The effectof the aggressionis counground,dorsalis efficiently and excludes umbrinusby means of interspecificag- terbalanced by the abilityof the subordinatespecies gressive encounters.The aggressionrapidly becomes to take refuge in some portion of the habitat from ineffectivewhen the trees become so closely spaced which the dominant species cannot displace it. that the more arboreal umbrinuscan readily escape. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In fact, once the densityof trees reaches a critical My wife,Astrid,providedinvaluableassistancewith level, umbrinus (which is more numerous and more tolerantof other chipmunksthan dorsalis) is able to all phasesof the project.G. A. Bartholomewand M. L. read and criticizedan earlierdraftof exclude dorsalis because the latter wastes excessive Cody have kindly The cooperationof the personnelof the the manuscript. time and energyon fruitlesschases. U. S. ForestServicein Bakerand Ely, Nevada, did much The interactingbehavioral mechanisms of exclu- to makethefieldworkpleasant. from sion betweenthese chipmunksare verydifferent LITERATURE CITED the simple physical destructionby crowdingthat ocand P. Ullyott.1932. Competitive A., R. S. Beauchamp, curs in barnacles (Connell 1961). In fact the partricertainspeciesof freshwater between relationships ticular combination of behavioral patterns in each clads. J.Ecol. 20: 200-208. species of chipmunkand the way that these interact Cody, M. L. 1968. On methodsof resourcedivisionin in interspecificencounters seems highly specialized grasslandbird communities.Amer. Naturalist102: 107-147. for this particular situation and hardly likely to be coma general featureof competitiveinteractions,even in Connell,J. H. 1961. The influenceof interspecific of the petitionand other factorson the distribution verysimilar,highlymobile vertebrates.In this regard barnacle Chthamalus stellatus. Ecology 42: 710-723. it is interestingto compare the resultsof the present Ecke, D. H. 1954. An invasionof Norwayratsin southstudywiththe unpublishedresultsof a studyby D. H. westGeorgia.J. Mammal. 35: 521-525. Sheppard (reported in Miller 1967) of competition Gause, G. F. 1934. The strugglefor existence.Williams and Wilkins,Baltimore. between two other species of chipmunks (Eutamias N. G. 1951. Interspeciescompetitionand its Hairston, minimum and E. amoenus) in westernAlberta, Canof Approbableinfluenceon the verticaldistribution ada. Some aspects of that interactionappear similar palacian salamandersof the genusPlethedon.Ecology to those between E. dorsalis and E. umbrinus,as the 32: 266-274. competitorsdivide the habitat on the basis of density Hall, E. R. 1946. Mammals of Nevada. Universityof CaliforniaPress,Berkeleyand Los Angeles. of vegetation and interspecificaggression plays an Istock, C. A. 1967. Transientcompetitivedisplacement importantrole in exclusion. Others, however, are bettles.Ecology48: in naturalpopulationsof whirligig quite different;the distributionof only one of the 929-937. species is limitedby competitiveexclusion, and it is Miller,R. S. 1967. Patternand processin competition. Adv. Ecol. Res. 4: 1-74. the forest-dwellingspecies that is more aggressive. and populations.SciT. 1962. Beetles,competition Park, From the fragmentarydata available, it also appears ence 138: 1369-1375. that most of the importantcomponentsof the inter- Ripley,S. D. 1961. Aggressiveneglectas a factorin inactions betweendorsalis and umbrinushave been imin birds.Auk 78: 366-371. competition terspecific plicated in cases of exclusion between other species Rosenzweig,M. L., and J. Winakur.1969. Population habitatsand enof both vertebratesand invertebrates.Interspecific ecologyof desertrodentcommunities: Ecology50: 558-572. complexity. vironmental aggression plays an important role in competitive Tanner,J. T. 1952. Black-cappedand Carolina Chickinteractionsbetween rats, mice, blackbirds, titmice, adees in the southernAppalachian Mountains.Auk hummingbirds,and ants (many sources reviewed by 69: 407-424.