The functions of affect in health communications and

advertisement

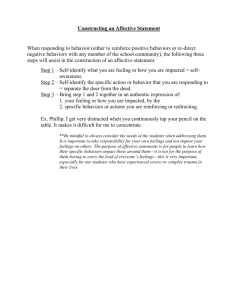

Journal of Communication ISSN 0021-9916 ORIGINAL ARTICLE The Functions of Affect in Health Communications and in the Construction of Health Preferences Ellen Peters1, Isaac Lipkus2, & Michael A. Diefenbach3 1 Decision Research, Eugene, OR 97401 2 Duke University Medical Center, Cancer Prevention, Detection and Control Program, Durham, NC 27701 3 Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Department of Urology, New York, NY 10029 We examine potential roles of 4 functions of affect in health communication and the construction of health preferences. The roles of these 4 functions (affect as information, as a spotlight, as a motivator, and as common currency) are illustrated in the area of cancer screening and treatment decision making. We demonstrate that experienced affect influences information processes, judgments, and decisions. We relate the functions to a self-regulation approach and examine factors that may influence the weight of cognitive versus affective processing of information. Affect’s role in health communication is likely to be nuanced, and it deserves careful empirical study of its effects on patients’ well-being. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00287.x A major theme that emerges from judgment and decision-making research is that we frequently do not know our own ‘‘true’’ values in decisions (e.g., how much we value a treatment option or better patient/physician communication). Rather, when asked to form a judgment or to make a decision, we often appear to construct our values and preferences ‘‘on-the-spot’’ using cues from the decision situation and our own internal reactions (Payne, Bettman, & Schkade, 1999; Slovic, 1995). This kind of on the spot value judgment can have significant implications for a person’s well-being, such as when cancer patients are asked to make treatment decisions. In health communications, the goal of communication efforts is often informed choice; decisions should be based on patients’ ‘‘accurate’’ understanding of the facts and be consistent with patient values (Briss et al., 2004; Edwards, Unigwe, Elwyn, & Hood, 2003; Frosch, Kaplan, & Felitti, 2001; Parascandola, Hawkins, & Danis, 2002). For example, a man who elects to be screened for prostate cancer by having a prostatespecific antigen test should understand and weigh the potential positive and negative outcomes of the test (e.g., a possible cancer diagnosis, anxiety while waiting for the Corresponding author: Ellen Peters; e-mail: empeters@uoregon.edu. S140 Journal of Communication 56 (2006) S140–S162 ª 2006 International Communication Association E. Peters et al. The Functions of Affect results, the possible need to undergo additional tests such as a biopsy related to an abnormal finding that proves not to be cancer) with the likelihood of each outcome. However, although the goal of informed choice is an excellent one, it may not attend adequately to the possibility that value judgments and preferences of patients are malleable and are sometimes constructed on the spot. As a result, informed choice may be a less realistic ideal in some situations (e.g., when how information is presented as opposed to what information is presented exerts a significant impact on choices). In other medical situations, the goal of health communication is to persuade (e.g., a 14-year-old vulnerable to smoking should be persuaded not to initiate smoking). With this goal, communicators are attempting to harness the power of constructed values and preferences. We examine the roles of affect and the affect heuristic in health communication and the construction of health preferences. This study extends earlier work on the affect heuristic by examining four functions of affect in the construction process. We first review the four functions developed by Peters (in press) and illustrate these processes with examples relating to cancer screening and treatment. Research demonstrates that affect experienced in the moment, whether the result of considering a decision option or from an unrelated source, influences concurrent cognitions, information processes, judgments, and decisions. Subsequently, we relate the functions to a self-regulation approach to health threats that includes both affective and cognitive components. Finally, we examine factors that may influence the weight of more cognitive versus more affective processing of health information. What are the functions of affect in the process of constructing judgments and decisions? Recent research has developed and tested theories of judgment and decision making that incorporate affect as a key component in a process of constructing values and preferences (Lichtenstein & Slovic, in press). Within these theories, integral affect refers to positive and negative feelings1 about a stimulus that are generally based on prior experiences and thoughts and are experienced while considering the stimulus, whereas incidental affect is positive and negative feelings such as mood states that are independent of a stimulus but can be misattributed to it or can influence decision processes. Together, they are used to predict and explain a wide variety of judgments and decisions ranging from choices among jelly beans to life satisfaction and valuation of human lives (Kahneman, Schkade, & Sunstein, 1998; Schwarz & Clore, 1983; Slovic, Finucane, Peters, & MacGregor, 2002). Mild incidental affect and integral affect are ubiquitous in everyday life. Imagine finding a quarter on the sidewalk (a mild positive mood state is induced; there may be a ‘‘carryover’’ of incidental affect that colors your next decision even though the feelings are not normatively relevant to the decision) or considering whether you will have a bowl of oatmeal or a chocolate croissant for breakfast (mild positive and negative affect are experienced; these are termed integral affect because they are part Journal of Communication 56 (2006) S140–S162 ª 2006 International Communication Association S141 The Functions of Affect E. Peters et al. of the decision maker’s internal representation of the decision options). Feelings experienced in the cancer context can be more extreme. For example, a breast cancer survivor may experience a euphoric mood state when told that she is in remission or a 65-year-old man with prostate cancer may use integral affect toward his options of watchful waiting and surgery to guide his treatment choice. Whether mild or strong, these feelings can impact the processing of information and, thus, what is judged or decided. Research has begun to delineate the various ways that affect alters information processing. In this study, we argue that affect has four separable roles important to health communication and decision-making processes. First, as suggested above, affect can act as information. Second, it can act as a spotlight focusing our attention on different information—numerical cues or risks versus benefits, for example—depending on the extent of our affect. Third, affect can motivate action or the processing of information. Finally, affect may serve as a common currency in judgments and decisions, allowing us to compare more effectively the values of very different decision options or information (e.g., compare apples to oranges). These functions are not mutually exclusive, and we consider their interrelations after introducing all four functions. We will focus primarily on valence (positive and negative) feelings because this evaluation has been found essential to meaning by researchers studying such diverse phenomena as language, attitudes, and the behavior of persons with brain lesions (see, e.g., Damasio, 1994; Osgood, Suci, & Tannenbaum, 1957). Consideration of how discrete emotion states impact preferences and when valence versus discrete emotions alter preferences are also important questions but are outside the scope of this study (Lerner & Tiedens, in press; Peters, Burraston, & Mertz, 2004). Affect as information One of the most comprehensive theoretical accounts of the role of affect and emotion in decision making was presented by the neurologist, Antonio Damasio (1994). In seeking to determine ‘‘what in the brain allows humans to behave rationally,’’ Damasio argued that a lifetime of learning leads decision options and attributes to become ‘‘marked’’ by positive and negative feelings linked directly or indirectly to somatic or bodily states. When a negative somatic marker is linked to an outcome, it acts as information by sounding an alarm that warns us away from that choice. When a positive marker is associated with the outcome, we are drawn toward that option. By consulting and being guided by these feelings, Damasio claims that we make better quality and more efficient decisions. Without these feelings, information in a decision lacks meaning and the resulting choice suffers. The affect heuristic built upon these and other ideas to suggest that affect may serve as a cue for many important judgments including probability judgments (Slovic et al., 2002). Zajonc (1980) proposed that affective reactions to stimuli are often the earliest reactions. Under the affect heuristic model, affect can be experienced first upon consideration of a familiar technology or it can be the result of further processing of information (LeDoux, 1996; Peters, Västfjäll, et al., 2006). In S142 Journal of Communication 56 (2006) S140–S162 ª 2006 International Communication Association E. Peters et al. The Functions of Affect either event, the affect then acts as information guiding decisions and judgments such as risk and benefit perceptions. The affect heuristic is substantially similar to models of ‘‘risk as feelings’’ and ‘‘mood as information’’ (Loewenstein, Weber, Hsee, & Welch, 2001; Schwarz & Clore, 2003) and shares much in common with dual process theories, such as those by Epstein (1994) and Leventhal (e.g., Cameron & Leventhal, 2003; Leventhal, 1970; Leventhal, Diefenbach, & Leventhal, 1992). Whereas some theories focus exclusively on the use of mood states (incidental affect) in judgments (Forgas, 19952; Schwarz & Clore, 2003), use of the affect heuristic is characterized by reliance on feelings attributed to an option or stimulus and experienced while considering it in judgments and decisions. Alhakami and Slovic (1994) proposed that the strength of positive or negative affect associated with an activity (and experienced while considering that activity) guided perceptions of its risks and benefits. Thus, judgments about a technology such as a new medical treatment would be based not only on what people think about the treatment but also on how they feel about it. If feelings toward a technology are favorable, decision makers are moved toward judging its risks as low and its benefits as high; if their feelings are more negative, they tend to judge the opposite—high risk and low benefit. For example, virtual colonoscopy is currently under much scrutiny for the detection of colon cancer. Individuals with positive affect toward this technology (the affect may be due to prior learning that it is not invasive or it is less embarrassing) may interpret new information about risks and benefits in ways that are consistent with their affect (i.e., perceive it as low risk and high benefit). In some situations, decision options are unfamiliar to the decision maker and focused communication efforts may be able to assist the individual. In these cases, providing individuals with ‘‘affective cues’’ may help provide meaning to the information presented. For example, Peters, Slovic, & Hibbard (2004) were interested in the processes by which decision makers might bring meaning to unfamiliar, dry, cold facts about health plan quality. In a series of studies, they influenced the interpretation and comprehension of numerical information about health plan attributes by providing affective cues that can be used easily to evaluate the overall goodness or badness of a health plan. For example, in one of the studies, older adult participants were presented with identical attribute information (quality of care and member satisfaction) about two health plans. The information was presented in bar chart format with the actual score displayed to the right of the bar chart (see Figure 1). The information for half of the subjects was supplemented by the addition of affective categories (i.e., the category lines plus affective labels that placed the health plans into categories of poor, fair, good, or excellent). The attribute information was designed such that Plan A was good on both attributes, whereas Plan B was good on quality of care but fair on member satisfaction. The specific scores for quality of care and member satisfaction were counterbalanced across subjects, such that for half the subjects the average quality-of-care scores were higher, and for the other half average member satisfaction scores were higher. They predicted and found that affective categories influenced the choices. Journal of Communication 56 (2006) S140–S162 ª 2006 International Communication Association S143 The Functions of Affect E. Peters et al. Specifically, older adults preferred health Plan A more often when the categories were present (Plan A was always in the good affective category when the affective labels were present). In a second study, they found that choices of older adults with high deliberative ability (high speed of processing measured in a digit symbol substitution task) were influenced less by the presence versus absence of affective categories than were choices of older adults with low deliberative ability. The results suggest that adults with high deliberative efficiency are better able to compare information and derive meaning from the data. However, for adults with low deliberative efficiency, affective categories appear to provide more information and influence its meaning— suggesting that affective labels may be especially useful among those who are taxed by too much information, time pressure, or the stress of illness. Allowing individuals such as a recently diagnosed cancer patient access to the meaning of important information like the quality of care offered at different hospitals should help them to process it more deeply and make better decisions. A condition that included the category lines but no affective labels had no impact on choice, suggesting that categorization alone cannot explain this effect. A third study provided direct evidence of the affective basis of this manipulation by demonstrating that decision makers accessed their feelings about the health plan highlighted by affective categories (e.g., Plan A in Figure 1) faster than their thoughts in the presence but not in the absence of Condition 1: Affective categories Condition 2 : No affective categories Quality of care received: 0 40 Poor 60 Fair 80 Good Plan A 100 Excellent Plan A 61 Plan B 100 0 61 Plan B 65 65 Member satisfaction with HMO : 0 40 Poor Plan A Plan B 60 Fair 80 Good 63 59 100 0 100 Excellent Plan A Plan B 63 59 Figure 1 Example of affective categories in health plan choice. S144 Journal of Communication 56 (2006) S140–S162 ª 2006 International Communication Association E. Peters et al. The Functions of Affect the manipulation. Communication techniques such as these may prove useful in improving risk comprehension when cancer-related distress is high and objective risks are underweighted (Lerman et al., 1995). Although testing in a real-world environment is absolutely necessary, if affectively based attitudes are best modified with affective as opposed to cognitive information (Millar & Tesser, 1989), then cancer risk communication techniques with an affective basis may promote better comprehension of information like objective risks that might otherwise be ignored. The use of methods such as affective categories does call, however, for a different emphasis in health and other communications. Instead of a focus on providing complete and accurate information, the emphasis shifts to providing usable, meaningful, and accurate information that will support better choices. It brings with it a new level of responsibility for health communicators (including physicians and other health professionals) who would need to know how patients currently respond to information and would need to bring their expertise to bear not only on what information to provide but also on how to present that information in ways that ethically support good decision making. It also requires a delicate balance between informing patients and helping them take into account important information that might otherwise not enter into their decision processes. The provision of more subjective interpretations may be difficult and be resisted by health professionals who prefer to provide only ‘‘objective facts.’’ We hope this study helps shift the focus on patient best interests from exposing them to information to helping them comprehend and use that information. Affect also acts as information in the construction of risk estimates (Johnson & Tversky, 1983; Loewenstein et al., 2001; Peters & Slovic, 1996). Peters, Slovic, Hibbard, and Tusler (2006) linked affect to an adjustment process in fatality estimates. They found that decision makers asked to estimate the number of fatalities in the United States each year from various causes of death were influenced by the anchor provided (the actual number of deaths from a disease), a typical finding in such studies. The decision makers also appeared to adjust away from the anchor based on the extent of their worry about the disease under consideration; fatality estimates were significantly higher for causes of death about which they reported greater worry. These findings are among the first to link affect as a possible mechanism underlying the adjustment process (see also Peters, Slovic, & Gregory, 2003). They are also consistent with cancer results. For example, in the breast cancer literature, worry is associated with perceived risk (Erblich, Bovbjerg, & Valdimarsdottir, 2000; Lipkus et al., 2000).3 Although the direction of this effect is not entirely clear, experimental results have demonstrated that increasing incidental negative affect subsequently increases risk perceptions across a variety of domains (e.g., Johnson & Tversky). A pervasive fear of cancer may underlie in part the tendency for individuals to exaggerate their cancer risk (Croyle & Lerman, 1999). Reliance on affect as information may create communication challenges with respect to cancer risk. Specifically, reliance on affect may result in less use of (nonaffective) numerical information, making it difficult to educate patients about their Journal of Communication 56 (2006) S140–S162 ª 2006 International Communication Association S145 The Functions of Affect E. Peters et al. objective risk and alleviate unnecessary cancer distress (Watson et al., 1999). In one nonhealth-related study, the presence of salient affective cues led to neglect of probabilistic information (Rottenstreich & Hsee, 2001). We speculate that individuals’ often strong negative affect about cancer may create insensitivity to its (often relatively low) objective risk. In support of this notion, Kraus, Malmfors, and Slovic (1992) found that expert toxicologists were able to assess accurately the risk of cancer posed by different exposure levels to a toxic agent, but the average individual from the public tended to believe that any exposure level was risky, possibly because negative feelings about cancer created an insensitivity to varying levels of the likelihood of cancer. If the strength of affect toward an outcome causes neglect of its likelihood of occurrence as hypothesized, then probability neglect may be particularly strong among patients who have stronger negative reactions to cancer initially. Anxiety in the face of low objective risk, however, may also encourage protective behaviors to avoid increased risk (e.g., using sunscreen to avoid skin cancer). Affect as information thus acts as a substitute for the assessment of other specified target attributes in judgment (e.g., what is the objective risk of cancer from a toxic agent? Kahneman, 2003). Without affect, information appears to have less meaning and to be weighed less in cancer judgment and choice processes (e.g., numerical risk information). Communication efforts should include statements that acknowledge a person’s possible emotional reactions to a threat (e.g., it is quite normal to be worried in a situation like this) or illustrate the prevalence of the threat (e.g., prostate cancer is the most diagnosed cancer in the United States). Another example, within the context of genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility, illustrates this approach further. To improve understanding of testing-related probabilities and decision making, women eligible for genetic testing for BRCA1/2 are led through a structured exercise in which they imagine receiving a positive, negative, or indeterminate result. In each case, they are asked to imagine what they would feel and what they would think; the researcher’s goal was to identify potential maladaptive emotional and cognitive reactions that can be addressed by the genetic counselor (Diefenbach & Hamrick, 2003). This is one of the special efforts being developed to highlight the meaning of important, but underweighted, numerical information. Affect as a spotlight Considerably less work has been done on the other three proposed functions of affect in the construction of preferences. Peters (in press) proposed that affect plays a role as a spotlight in a two-step process. First, the extent or type of affective feelings (e.g., weak vs. strong affect or anger vs. fear) focuses the decision maker on new information. Second, the new information (rather than the initial feelings themselves) is used to guide the judgment or decision. Although incidental feelings have been shown to function as a spotlight in memory and judgment (e.g., moodcongruent biases on memory; Bower, 1981), little research has examined how integral feelings about a target might alter what information becomes more salient in decisions. S146 Journal of Communication 56 (2006) S140–S162 ª 2006 International Communication Association E. Peters et al. The Functions of Affect Nabi (2003) experimentally manipulated integral affect (anger vs. fear) toward drunk driving. Consistent with the proposed two-step approach, this affect manipulation first made some stored knowledge more accessible (e.g., reasons to be angry about drunk driving were spotlighted), and second, the more accessible information had a greater impact in subsequent preferences. Peters et al. (2003) found a similar spotlight effect with affect influencing the dollar values salient to buyers and sellers of a lottery ticket. Both level of affect toward an object and the types of affect (e.g., anger vs. fear) appear to make different cues more salient. Depending upon how people feel about an object, they may focus on different information. The function of affect as a spotlight takes advantage of the role of feelings in directing cognitions to address the source of the feeling. Alhakami and Slovic (1994) demonstrated that the negative correlation between perceived risk and perceived benefit is mediated by affect. For example, decision makers with positive affect toward a radiation source (e.g., X rays) tend to perceive it as highly beneficial and low in risk; the reverse happens if decision makers have negative affect about a radiation source (e.g., nuclear power). Although this effect has been interpreted in terms of the role of affect as information (Slovic et al., 2002), it may be related to affect’s role as a spotlight. The affect-as-spotlight hypothesis predicts that new benefit information will be more salient for decision makers who had previously developed positive feelings about a treatment or screening option. As a result, they will spend more time looking at and will remember more of the new benefit information, whereas they spend less time looking at any new risk information and will remember them less well. It predicts the reverse for treatment and screening options people evaluate negatively (e.g., less time spent considering and poorer memory for new benefit information). Thus, current affective experiences will guide the processing of cancer communications from physicians, decision aids, the media, and other sources. For example, in choices among screening options for colon cancer, negative feelings about contact with one’s own fecal matter may lead decision makers to spend more time examining its risks (lower accuracy rate) and less time examining its benefits. Knowing this might lead to a communication strategy of increasing positive mood in order to alter the negative feelings elicited during consideration of that option (or one could try to attenuate the negative affect elicited by making any fecal contact as abstract or normal as possible). No studies exist to the best of our knowledge testing these hypotheses. On a larger conceptual level, this means that we may need to tailor our communication approaches to a person’s emotions (see also Loewenstein, 2005). Affect as a motivator of information processing and behavior In a third role, affect appears to function as a motivator of information processing and behavior. Classical theories of emotion include, as the core of an emotion, a readiness to act and the prompting of plans (Frijda, 1986). Although affect is generally a much milder experience compared to a full-blown emotion state, recent research has demonstrated that we tend to automatically classify stimuli around us as Journal of Communication 56 (2006) S140–S162 ª 2006 International Communication Association S147 The Functions of Affect E. Peters et al. good or bad and that this tendency is linked to behavioral tendencies. Stimuli classified as good elicit a tendency to approach, whereas those classified as bad elicit avoidance tendencies (Chen & Bargh, 1999). Incidental mood states also motivate behavior as people tend to act to maintain or attain positive mood states (Isen, 2000). In addition, there is abundant research showing that some emotions, such as worry, have been used to motivate specific behavioral change, such as mammography screening (McCaul, Branstetter, Schroeder, & Glasgow, 1996). Diefenbach, Miller, and Daly (1999), for example, demonstrated that worry about breast cancer predicted mammography screening independent of perceived breast cancer risks and trait anxiety.4 Several reviews explicate the role of fear appeals as a motivator of behavior change (e.g., Leventhal, 1970; Sutton, 1982; Witte, 1998). Affect also appears to be linked to the extent of deliberative effort decision makers are willing to put forth in order to make the best decision (i.e., the extent of systematic processing). Peters et al.’s (2003) studies of how people price lottery tickets were sometimes played for real money and other times were hypothetical. Although the same general effects emerged in both types of studies, real play elicited stronger feelings about the lottery tickets. At the same time, the real-play participants showed more evidence of taking the effort to calculate an expected value (40% of real-play buyers gave the expected value as their response compared to 10% of hypothetical-play buyers). In addition, half the hypothetical-play participants showed evidence of less effort in another way by giving the same buying price as their earlier selling price; only 3% of real-play participants did so. Thus, real play seemed to motivate buyers and sellers to work harder, and the motivating effect of real play was mediated by affect. These findings suggest that individuals (whether patients, family members, or friends) who have strong affect about cancer may work harder to find and process information about treatment or other options. Of course, Isen’s (2000) work on decision makers motivated to maintain or attain positive moods suggests that decision makers in negative moods from cancer diagnosis or other reasons may avoid making choices if they do not believe that the work to make the choice will lead to more positive or at least less negative moods. Thus, increased negative affect about cancer risk may lead to coping efforts and, for example, increased genetic testing when the potential for controlling risk is high (e.g., breast cancer) but decreased testing when risk reduction is not possible (e.g., Huntington’s disease; Croyle & Lerman, 1999). An additional source of motivation from affect may come from the negative feelings elicited by ambivalence. At times, our emotions and thoughts do not perfectly align themselves as positive or negative. Instead, objects or tasks are evaluated as having both positive and negative qualities. For example, smokers often have conflicting (ambivalent) emotions and thoughts about smoking (Lipkus, Green, Feaganes, & Sedikides, 2001; Lipkus et al., 2005). The decision to get a mammogram may involve weighing its benefits (e.g., gaining peace of mind, being responsible for one’s health) against its potential costs (e.g., pain, fear of finding cancer). In this S148 Journal of Communication 56 (2006) S140–S162 ª 2006 International Communication Association E. Peters et al. The Functions of Affect instance, ambivalence could hinder the decision to get a mammogram (Rimer et al., 2002). Thus, in situations where the targeted behavior is related to positive health outcomes, ambivalence may be detrimental; conversely, ambivalence may serve a useful purpose by motivating change in unhealthy behaviors (e.g., smoking, drinking).5 We suspect that having ambivalent thoughts and feelings (Priester & Petty, 1996) may act as an important cue that triggers information search and influences decision making. Specifically, because the presence of opposing positive and negative beliefs and feelings is experienced as emotionally aversive (and a negative mood state results), the ambivalent individual is expected to engage in decisional conflict management strategies (Weber, Baron, & Loomes, 2001). Within the framework of conflict and decision-making models, ambivalence is assumed to trigger both problem-focused coping (e.g., what will help me decide?) and emotion-focused coping (e.g., how do I handle my ambivalent feelings? Haenze, 2001; Lazarus, 1991; Luce, 1998; Luce, Payne, & Bettman, 2001). Problem-focused coping should cause the person to devote more effort and thought to what action(s) seems appropriate (Haenze, 2001; Jonas, Diehl, & Bromer, 1997; Maio, Bell, & Esses, 1996). Emotion-focused coping should cause the person to engage in strategies to alleviate negative emotions (Haenze, 2001). In both cases, the negative mood state generated from facing difficult trade-offs motivates action to reduce uncertainty in decisions. Strategies to reduce uncertainty may take the form of turning to friends, experts, or other sources (e.g., written materials) to solve the dilemma. For example, a prostate cancer patient who is torn about which treatment, if any, to pursue may use these sources to gain insight, help clarify values, and inform the final decision. Alternatively, the other functions of affect may become more relevant. For example, if a prostate cancer patient feels ambivalent about a type of treatment (e.g., seed implant), the ensuing negative mood state may act as a spotlight and cause the patient to focus more on the risks than the benefits of this procedure. As a result, the patient may decide against having this treatment. Ambivalence may incorporate our notions of affect as a spotlight on certain features of a treatment with the notion of affect as a motivator of action. Future research could examine the effects of ambivalence on preferences, judgments, and decisions and on the communication efforts that might best facilitate good decisions. Affect as common currency Affect is simpler in some ways than thoughts. Affect often comes in two ‘‘flavors,’’ positive and negative; thoughts include more, and more complex, cost-benefit and other trade-offs (Trafimow & Sheeran, 2004). Several theorists have suggested that, as a result, integral affect plays a role as a common currency, allowing decision makers to compare apples to oranges (Cabanac, 1992). Montague and Berns (2002) link this notion to ‘‘neural responses in the orbitofrontal-striatal circuit which may support the conversion of disparate types of future rewards into a kind of internal currency, that is, a common scale used to compare the valuation of future behavioral acts or stimuli’’ (p. 265). By translating more complex thoughts into Journal of Communication 56 (2006) S140–S162 ª 2006 International Communication Association S149 The Functions of Affect E. Peters et al. simpler affective evaluations, decision makers can compare and integrate good and bad feelings rather than attempt to make sense out of a multitude of conflicting logical reasons. This function thus is an extension of the affect-as-information function into more complex decisions that require integration of information. It predicts that affective information can be more easily and effectively integrated into judgments than less affective information. In the health plan choice studies of Peters, Slovic, et al. (2004), affective categories were hypothesized to act as overt markers of affective meaning in choices. If correct, then these overt markers should help participants consider relevant information (i.e., not considered as much when affective categories are not present) and apply that information to a complex judgment. Thus, affective categories should influence not just the choice of a health plan, as shown in previous studies, but should also help decision makers take into account more information and be more sensitive to variation in information. In an initial test of this hypothesis, participants were asked to judge a series of eight health plans one at a time on a 7-point attractiveness scale ranging from 1 = extremely unattractive to 7 = extremely attractive. For each health plan, they received information about cost and two quality attributes presented with numerical scores (e.g., Plan A scored 72 out of 100 points when members of the health plan rated the ‘‘ease of getting referrals to see a specialist’’). The eight health plans represented a 2 3 2 3 2 design of low and high scores on each of the three attributes; eight versions were constructed using a Latin square design. Participants who received the quality information with affective categories (poor, fair, good, excellent) took into account more information and showed significantly greater sensitivity to differences in quality among plans. Thus, providing information in a more affective format appeared to help these judges better integrate important quality information into their judgments. Of course, it is also possible that these results reflect affect’s function as a motivator of behavior. Specifically, the affective categories manipulation may have produced a greater affective reaction that motivated the judges to work harder and integrate more information. These questions are empirical and deserve further research. Communicating the risks and benefits of cancer treatment and screening options can be quite difficult due to the complexity of information. It may be that providing this information in a more affective format might help patients integrate more information and thus make more informed choices. Relations among the four functions of affect The four functions of affect clearly are interrelated (see Figure 2). Affect, experienced due to an incidental source or upon consideration of some stimulus, can provide direction to cognition and be used as information and/or it can promote an automatic readiness to act and motivate information processing and behaviors (Oatley & Jenkins, 1996). If affect is used as information, it can be used as a substitute for other information in making a judgment (the direct line from affect as information to judgment) S150 Journal of Communication 56 (2006) S140–S162 ª 2006 International Communication Association E. Peters et al. The Functions of Affect Judgment Affect as information Affect Affect as common currency Affect as spotlight Affect as motivator New information Behavior or further information processing Figure 2 Hypothesized relationships among the functions of affect. or it can lead to the use of affect as common currency when multiple pieces of information need to be combined. In this case, the affective information from multiple sources will be highlighted in the integration process; less affective information may receive less weight in the judgment process because it is not as easily integrated as the affective information. Finally, affect can be used as information to guide the selection of other information to process. This new information is highlighted and then used in the subsequent judgment. New affect could result from this process and take on a function of its own (e.g., negative affect from a cancer diagnosis could lead a patient to examine the risks more than the benefits of some treatment; if the risks are relatively small and elicit only slight negative affect, the function of affect as common currency might take over and the combination of the original affect from the diagnosis and the relatively neutral affect from the risks might lead to overall lower negative affect toward the cancer). If affect is used as a motivator of information processing and behaviors, it could lead simply to a health behavior of getting a mammogram, for example, or it might lead to more deep processing of information, coping efforts (including the avoidance of information that might lead to further distress), or communication to others. Each of these motivated processes and behaviors could lead to new affect that then takes on another function. Health communication efforts often have as their goal inducing long-term positive change in health-related behaviors. However, in research guided by the elaboration likelihood model, sources of affect incidental to a decision option (e.g., a mood state, the source of a message such as a famous liked person) have been found to evoke less systematic processing and less enduring attitude change than Journal of Communication 56 (2006) S140–S162 ª 2006 International Communication Association S151 The Functions of Affect E. Peters et al. might be helpful in health communication (Petty, Barden, & Wheeler, 2002), suggesting that the use of affect is generally detrimental to this cause. But in most of these cases, the judgments were not necessarily very important or personally relevant. In cases where the opposite holds (e.g., high personal relevance), emotions can evoke the opposite response and may themselves receive greater scrutiny (Petty, DeSteno, & Rucker, 2001). We believe that integral affective sources (e.g., a cancer patient’s feelings elicited as he considers the pros and cons of a course of treatment) may increase the elaborations of health message recipients by directing attention, memory, and judgment to address the affect-eliciting event (affect’s function as a spotlight). The ability to process the message also may increase through the functions of affect as information and affect as common currency as data become meaningful information through affect (Hsee, Loewenstein, Blount, & Bazerman, 1999); the motivation to process and the extent of processing may increase through the function of affect as a motivator. It would be useful to include a manipulation of argument quality in further health communication tests of the functions of affect in order to examine more closely the processes underlying these effects. Functions of affect in health behavior theories Considering different functions of affect may help in further development of health behavior theories. Traditionally, health behavior theories have a strong cognitive orientation, focusing on health beliefs, expectations, social norms, and goals to predict health behaviors such as decisions to quit smoking, adhere to a weight loss program, or obtain a colonoscopy (Janz & Becker, 1984, Fishbein & Ajzen, 2005). The exception to this predominant cognitive orientation in health behavior theorizing is the self-regulation framework (Cameron & Leventhal, 2003; Petrie & Weinman, 1997) that explicitly takes into account affective reactions to a stimulus as determinants of health behavior. The self-regulation framework has its origin in the parallel processing model (Leventhal, 1970) that hypothesizes that individuals process external and internal stimuli (e.g., a message from their health plan to obtain a mammogram; detection of a lump) on both cognitive and emotional levels simultaneously. The self-regulation model regards the individual as a ‘‘problem solver’’ who actively attempts to make sense of environmental and somatic stimuli using both cognitive and affective processes (Leventhal et al., 1997). On the cognitive processing level, a stimulus is categorized according to five cognitive attributes that encompass the dimensions of identity (i.e., the attempt to name or label a stimulus), timeline (i.e., acute vs. chronic), cause (e.g., genetic, accident, exposure), consequence (i.e., minor vs. life threatening), and controllability (remedy vs. no remedy; Lau, Bernard, & Hartman, 1989). On the affective processing level, the stimulus evokes an affective response that interacts with the cognitive appraisal of the stimulus (Diefenbach et al., 1999). For example, imagine a person taking a shower and detecting a lump in the axilar region. The immediate response might be one of fear (i.e., affective response) accompanied by the simultaneous thought that it might be S152 Journal of Communication 56 (2006) S140–S162 ª 2006 International Communication Association E. Peters et al. The Functions of Affect cancer (i.e., identity attribute). The cancer label might trigger related thoughts such as, ‘‘this is serious’’ (i.e., consequence), ‘‘I have to deal with this for a long time’’ (i.e., timeline), ‘‘I don’t know where this comes from’’ (i.e., cause), and ‘‘there is treatment available’’ (i.e., controllability). Each of these attributes can trigger specific emotions and not all attributes might be present at the same time. Of course, this interplay between cognition and emotion might take a different trajectory as self-regulation theory does not specify a fixed sequence among cognitive or emotional processing (Brissette, Leventhal, & Leventhal, 2003). What is important, however, is that this model provides a framework for affective functioning within a larger context of cognitive activity and recognizes that behavioral actions can be triggered as much by affective reactions as by cognitive processing. To continue with the example above, the individual might conclude to consult a physician about the lump because of her evaluation that it might be cancerous. However, she might also seek professional advice because her anxiety becomes unbearable and she needs reassurance (note that high levels of worry also might be associated with avoidant behavior). Although research has confirmed the existence of the cognitive attributes describing a stimulus, much less research has focused on affective processing mechanisms (Cameron & Leventhal, 2003). We argue that consideration of affect as having multiple functions provides a promising approach to enriching health behavior theories. The example above suggests that the traditional self-regulation framework recognizes two of the four affect functions: affect as information and affect as motivator. The individual instantaneously categorizes the lump as ‘‘something bad’’ and experiences elevated levels of anxiety; these feelings may be used as information to judge her cancer risk as high and may motivate her to seek professional advice quickly about diagnosis and treatment as well as about how to cope with the feelings themselves. During further cognitive and affective processing, the role of affect as a spotlight might come into play. Elevated levels of worry might lead her to focus more on potential negative interpretations and outcomes (affect-as-spotlight function), possibly ignoring benign interpretations of the lump (e.g., the lump is a bruise). Finally, across all the various internal and external information available to the individual, the affective information (e.g., worry about the lump, relief from a news story about a similar woman who found out her lump was not cancerous) may be integrated more and more easily than nonaffective information into ongoing evaluations of her risk, thus providing evidence for the affect-as-common currency function. This also underscores the need for a comprehensive theoretical framework that attempts to integrate different areas of research. Trade-offs between affect and deliberation Affect and cognitions both play a role in constructing preferences. The weight of one versus the other in judgments and choices, however, may be dictated in part by contextual factors. One such factor might be the importance or relevance of the decision. Clearly, choices of a life-saving treatment (e.g., what is the best cancer Journal of Communication 56 (2006) S140–S162 ª 2006 International Communication Association S153 The Functions of Affect E. Peters et al. therapy) versus a weekend movie differ in importance. We suspect that when decisions are not very important, individuals will spend little thought determining a course of action, but rather rely on their affect as a substitute (e.g., how do I feel about it?). At the other extreme, when the decision is important and consequential, individuals may rely on both what they think and how they feel about the pros and cons of each option. Under these situations, individuals are often motivated to reach the most accurate decisions; hence, we assume that these decisions will often involve more central/systematic processing than peripheral/heuristic processing (Forgas, 2000; Payne, Bettman, & Johnson, 1993). The most accurate decisions may rely on interactions between thoughts and feelings. For example, different affective states (e.g., anxiety) can promote more in-depth systematic processing of health-relevant information as well as prime information consistent with those mood states (Cameron, 2003; Forgas, 2000). Affect associated with an option through prior experiences may guide decision makers to better options (e.g., somatic markers; Damasio, 1994). However, incidental feelings such as mood states also can color the interpretation of information and, thus, bias the direction of its evaluation in potentially inappropriate situations (e.g., when critical life-saving treatments need to be made). In some circumstances, individuals may become aware of the influence of their feelings on decisions, think the influence is inappropriate, and try to correct for it by relying on strategies based on their lay theories of how feelings may influence decisions (Petty & Wegener, 1993; Wegener & Petty, 1997). This combination of processes may lead to more accurate decisions. Other factors that may influence the weight accorded affective versus more cognitive information include decision complexity and familiarity. When a decision is complex because the person is faced with several nondominating options (i.e., no single option is superior to all others on the outcomes of interest, e.g., choices among prostate cancer treatment; Steginga & Occhipinti, 2004), too much information, or too technical information, the person may rely most on how they feel rather than on what they think—perhaps because they may not trust their evaluation of the facts or their ability to integrate multiple and competing reasons. Similarly, when the decision to be made can be equated with familiar past experiences, the individual may rely more on how they felt about the outcome(s) obtained rather than go through the effort of evaluating the pros and cons of each option (i.e., the affect-as-information function). For example, many individuals aged 50 and older are faced with the option of which method they should use to screen for colorectal cancer. Assuming some effort was put forth earlier thinking through available screening options (e.g., fecal occult blood test, sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy) and/or the person was pleased with how the procedure went (e.g., not too embarrassing or time consuming, was painless), when faced with the same situation, he or she may simply use the affective cues attached to outcome(s) experienced to determine which, if any, screening technique to use. Factors that interfere with a person’s ability to cognitively evaluate information also can cause the individual to weigh affect more than cognition in choice. Shiv and S154 Journal of Communication 56 (2006) S140–S162 ª 2006 International Communication Association E. Peters et al. The Functions of Affect Fedorikhin (1999), for example, found that decision makers under cognitive load were more likely to choose an affectively pleasing chocolate cake over a fruit salad compared to those in a no-load condition. For better or worse, cognitive load is ubiquitous in life. We are surrounded by environmental noises, interference, or distractions by others (e.g., phone calls, loud music, children, etc.), and we are plagued with busy schedules. These cognitive loads may be a particular burden to cancer patients faced, not only with their daily lives but also with the added stress and decisions of a potentially life-threatening disease. Another related influential factor that may tip the scale toward relying more on affect than on cognitions is time pressure (e.g., the need to quickly choose a treatment, being faced with a busy physician who has only a few minutes to provide information and answer questions). Finucane, Alhakami, Slovic, and Johnson (2000) found that the inverse correlation between risks and benefits grows larger under time pressure. Their findings suggest that the affective processes underlying perceptions of risks and benefits may weigh more when time for deliberation is low. In choices among cancer treatments, patients may be asked to make critical decisions immediately after diagnosis (e.g., treatment decisions about mastectomy vs. breast-conserving procedures and type of adjuvant treatment, if any, decisions about whether to enter a clinical trial, decisions about whom to tell and when; Revenson & Pranikoff, 2005). Many patients may feel delaying a decision is not an option. As a result, they may base their final decisions on how they feel because of the lack of perceived opportunity to reflect on the option(s). Finally, an important factor that may shape our emotional reactions, and hence preferences, is the information presentation format, such as in the health plan choice studies reviewed previously. A classic example is framing of information. Loss-frame messages emphasize the negative outcomes or benefits lost by taking or not taking some form of action; gain-frame messages emphasize positive outcomes or costs avoided by taking or not taking some form of action. The extant literature shows that losses loom larger than gains and hence are more influential in determining decisions and actions (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981). Thus, individuals are more likely to have adverse emotional reactions to information presented in terms of losses than gains (e.g., medical decisions in which treatment outcomes are framed in terms of lives lost vs. lives saved). In sum, differential weighting of cognitions and affect and affect itself are likely to be influenced by several contextual variables, some of which have been presented here. Admittedly, this is not an exhaustive listing. The main point here is that the influence of affect on the interpretation of health communications and the construction of health preferences is itself shaped by several situational factors that need to be considered. Is affect rational? Emotion’s influence on health decisions can be overwhelming. It can cause undue anxiety or fear, overestimation of risks (e.g., with breast cancer patients), and Journal of Communication 56 (2006) S140–S162 ª 2006 International Communication Association S155 The Functions of Affect E. Peters et al. avoidant choices among treatment options (e.g., avoiding a treatment with better long-term survival because it requires a colostomy). It can also be a distraction when it provides information or motivation to attend to or act on emotional information at the expense of other more important message content (e.g., a positive mammogram result and the emotions that ensue may distract a woman from the information that only 20% of women with positive mammograms have breast cancer). Often times when people consider the impact of emotion on health decisions, they think about these kinds of negative impacts. Damasio (1994), on the other hand, argues that integral affect in the form of somatic markers increases the accuracy and efficiency of the decision process, and its absence (e.g., in the brain-damaged patients) degrades decision performance. This view of affect likely is also true in the domain of cancer. Affect is rational in the sense that some level of integral affect is necessary for information to have meaning so that decisions can be made. This ‘‘affective rationality’’ is key for health communications that have normally focused less on the role of affect and more on deliberative means (Hibbard & Peters, 2003). Warning labels on cigarette packages in the United States, for example, focus on four statements informing smokers about health hazards; evidence concerning these labels suggests that they have little influence on tobacco sales and have become invisible compared to the more salient and colorful cigarette packages and advertising (Fischer, Krugman, Fletcher, Fox, & Rojas, 1993; Fischer, Richards, Berman, & Krugman, 1989). Survey research in Canada, however, suggests that their larger warning labels with color pictures and 16 separate messages about specific risks of smoking create more negative emotional reactions toward cigarettes and increase attempts to quit among smokers (Hammond, Fong, McDonald, Cameron, & Brown, 2003; Hammond, McDonald, Fong, Brown, & Cameron, 2004). Affect’s role in health communication is likely to be nuanced; it therefore deserves careful empirical study of its effects on patients’ well-being. Affect sometimes may help and other times hurt decision processes. Which occurs will depend on the affect elicited by the communication attempt, how affect influences the information processing that takes place in the construction of preferences and how that particular influence matches whatever processing will produce the best decision for the cancer patient in that situation. In other words, the presence of affect does not guarantee good or bad decisions; it does guarantee that communicated information will be processed in ways that are different from when it is not present. Understanding the latter processes presents important communication challenges. Acknowledgments This paper is based in part on the chapter ‘‘The functions of affect in the construction of preferences’’ by E. Peters, which will appear in S. Lichtenstein & P. Slovic (Eds.), The construction of preference. New York: Cambridge University Press. Preparation of this paper was supported in part by the National Science Foundation under grant S156 Journal of Communication 56 (2006) S140–S162 ª 2006 International Communication Association E. Peters et al. The Functions of Affect SES-0111941, SES-0339204, and SES-0241313. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. Notes 1 2 3 4 5 Emotion theorists continue to debate the structure of emotion. Although some theorists argue for a different rotation of emotion space (in particular, a 45 rotation that yields the two factors of valence and arousal), we have chosen to focus on the rotation that yields factors of positive and negative affect. Forgas (1995) considered only the influence of incidental affect in judgments. The first three functions proposed here, however, map somewhat onto his judgmental strategies. First, the integral affect of this study may be present as a component of a preexisting evaluation and thus may be experienced and used as the information in Forgas’ direct access strategy. In addition, the use of incidental affect as information overlaps completely with Forgas’ heuristic strategy. Second, similar to his substantive processing strategy, incidental or integral affect as a spotlight can influence attention, encoding, retrieval, and associative processes. Third, although incidental affect may not influence judgments in Forgas’ motivated processing strategy, integral affect, through its functions as a motivator, can drive the goals and behaviors of motivated processing. At extreme levels of negative affect, it may cease to provide information into a decision process and may instead prompt defensive processing of information. It is not clear whether there exists a particular level of affect that will prompt this change although Witte (1998) suggests that this ‘‘boomerang effect’’ will not occur so long as the decision maker perceives that he or she can exert some control over the situation. Some researchers have suggested that very high levels of cancer worry promote defensive avoidance of cancer screening behaviors (e.g., Lerman et al., 1993). If correct, then the specific behaviors motivated by affect may change depending upon the level of affect experienced. It may be that one level of affect promotes healthy screening behaviors, whereas an increase over some threshold produces avoidance, particularly in the absence of a concrete action plan (Leventhal, 1970). In the context where ambivalence hinders adaptive behaviors (e.g., getting a mammogram), communications may target reducing ambivalence. Such approaches may reduce the uncertainty and negative feelings associated with ambivalence, perhaps by helping people envision and make salient the positive aspects of behavior change. References Alhakami, A. S., & Slovic, P. (1994). A psychological study of the inverse relationship between perceived risk and perceived benefit. Risk Analysis, 14, 1085–1096. Bower, G. (1981). Mood and memory. American Psychologist, 36, 129–148. Briss, P., Rimer, B., Reilley, B., Coates, R. C., Lee, N. C., Mullen, P., et al. (2004). Promoting informed decisions about cancer screening in communities and healthcare systems. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 26, 67–80. Journal of Communication 56 (2006) S140–S162 ª 2006 International Communication Association S157 The Functions of Affect E. Peters et al. Brissette, I., Leventhal, H., & Leventhal, E. A. (2003). Observer ratings of health and sickness: Can other people tell us anything about our health that we don’t already know? Health Psychology, 22, 471–478. Cabanac, M. (1992). Pleasure: The common currency. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 155, 173–200. Cameron, L. D. (2003). Anxiety, cognition, and responses to health threats. In L. D. Cameron & H. Leventhal (Eds.), The self-regulation of health and illness behaviour (pp. 157–183). London: Routledge. Cameron, L. D., & Leventhal, H. (Eds.). (2003). The self-regulation of health and illness behavior. London: Routledge. Chen, M., & Bargh, J. A. (1999). Consequences of automatic evaluation: Immediate behavioral predispositions to approach or avoid the stimulus. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 25, 215–224. Croyle, R. T., & Lerman, C. (1999). Risk communication in genetic testing for cancer susceptibility. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs, 25, 59–66. Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes’ error: Emotion, reason, and the human brain. New York: Avon. Diefenbach, M. A., & Hamrick, N. (2003). Self-regulation and genetic testing: Theory, practical considerations, and interventions. In L. Cameron & H. Leventhal (Eds.), The self-regulation of health and illness behaviour. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic. Diefenbach, M. A., Miller, S. M., & Daly, M. (1999). Specific worry about breast cancer predicts mammography use in women at risk for breast and ovarian cancer. Health Psychology, 18, 532–536. Edwards, A., Unigwe, S., Elwyn, G., & Hood, K. (2003). Personalized risk communication for informed decision making about entering screening programs. The Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews, Issue No. 1, Art No. CD001865. Epstein, S. (1994). Integration of the cognitive and the psychodynamic unconscious. American Psychologist, 49, 709–724. Erblich, J., Bovbjerg, D. H., & Valdimarsdottir, H. B. (2000). Psychological distress, health beliefs, and frequency of breast self-examination. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 23, 277–292. Finucane, M. L., Alhakami, A., Slovic, P., & Johnson, S. M. (2000). The affect heuristic in judgments of risks and benefits. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 13, 1–17. Fischer, P. M., Krugman, D. M., Fletcher, J. E., Fox, R. J., & Rojas, T. H. (1993). An evaluation of health warnings in cigarette advertisements using standard market research methods: What does it mean to warn? Tobacco Control, 2, 279–285. Fischer, P. M., Richards, J. W., Berman, E. F., & Krugman, D. M. (1989). Recall and eye tracking study of adolescents viewing tobacco advertisements. Journal of the American Medical Association, 261, 84–89. Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2005). Theory-based change interventions: Comments on Hobbis and Sutton. Journal of Health Psychology, 10, 27–31. Forgas, J. P. (1995). Mood and judgment: The affect infusion model (AIM). Psychological Bulletin, 117, 39–66. Forgas, J. P. (2000). Feeling and thinking: The role of affect in social cognition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. S158 Journal of Communication 56 (2006) S140–S162 ª 2006 International Communication Association E. Peters et al. The Functions of Affect Frosch, D. L., Kaplan, R. M., & Felitti, V. (2001). Evaluation of two methods to facilitate shared decision making for men considering the prostate-specific antigen test. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16, 391–398. Frijda, N. H. (1986). The emotions: Studies in emotion and social interaction. New York: Cambridge University Press. Haenze, M. (2001). Ambivalence, conflict, and decision making: Attitudes and feelings in Germany towards NATO’s military intervention in the Kosovo war. European Journal of Social Psychology, 31, 693–706. Hammond, D., Fong, G., McDonald, P., Cameron, R., & Brown, K. (2003). Impact of the graphic Canadian warning labels on adult smoking behavior. Tobacco Control, 12, 391–395. Hammond, D., McDonald, P., Fong, G., Brown, K., & Cameron, R. (2004). The impact of cigarette warning labels and smoke-free bylaws on smoking cessation. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 95, 201–204. Hibbard, J. H., & Peters, E. (2003). Supporting informed consumer health care decisions: Data presentation approaches that facilitate the use of information in choice. Annual Review of Public Health, 24, 413–433. Hsee, C. K., Loewenstein, G., Blount, S., & Bazerman, M. H. (1999). Preference reversals between joint and separate evaluations of options: A review and theoretical analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 576–590. Isen, A. M. (2000). Some perspectives on positive affect and self-regulation. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 184–187. Janz, N. K., & Becker, M. H. (1984). The health belief model: A decade later. Health Education Quarterly, 11, 1–47. Johnson, E. J., & Tversky, A. (1983). Affect, generalization, and the perception of risk. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 20–31. Jonas, K., Diehl, M., & Bromer, P. (1997). Effects of attitudinal ambivalence on information processing and attitude-intention consistency. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 33, 190–210. Kahneman, D. (2003). A perspective on judgment and choice: Mapping bounded rationality. American Psychologist, 58, 697–720. Kahneman, D., Schkade, D., & Sunstein, C. R. (1998). Shared outrage and erratic awards: The psychology of punitive damages. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 16, 49–86. Kraus, N., Malmfors, T., & Slovic, P. (1992). Intuitive toxicology: Expert and lay judgments of chemical risks. Risk Analysis, 12, 215–232. Lau, R. R., Bernard, T. M., & Hartman, K. A. (1989). Further explorations of common-sense representations of common illnesses. Health Psychology, 8, 195–219. Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. American Psychologist, 46, 819–834. LeDoux, J. E. (1996). The emotional brain: The mysterious underpinnings of emotional life. New York: Simon & Schuster. Lerman, C., Daly, M., Sands, C., Balshem, A., Lustbader, E., Heggan, T., et al. (1993). Mammography adherence and psychological distress among women at risk for breast cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 85, 1074–1080. Lerman, C., Lustbader, E., Rimer, B. K., Daly, M., Miller, S., Sands, C., et al. (1995). Effects of individualized breast cancer risk counseling: A randomized trial. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 87, 286–292. Journal of Communication 56 (2006) S140–S162 ª 2006 International Communication Association S159 The Functions of Affect E. Peters et al. Lerner, J. S., & Tiedens, L. Z. (2006). Toward a model of emotion-specific influences on judgment and decision making: Portrait of the angry decision maker. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 19, 115–137. Leventhal, H. (1970). Findings and theory in the study of fear communications. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 5, pp. 119–186). New York: Academic Press. Leventhal, H., Benjamini, Y., Brownlee, S., Diefenbach, M. A., Leventhal, E. A., Patrick-Miller, L., et al. (1997). Illness representations: Theoretical foundations. In K. J. Petrie & J. A. Weinman (Eds.), Perceptions of health and illness: Current research and applications (pp. 19–45). Amsterdam: Harwood Academic. Leventhal, H., Diefenbach, M. A., & Leventhal, E. A. (1992). Illness cognition: Using common sense to understand treatment adherence and affect cognition interactions. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 16, 143–163. Lichtenstein, S., & Slovic, P. (Eds.). (in press). The construction of preference. New York: Cambridge University Press. Lipkus, I. M., Green, J. D., Feaganes, J. R., & Sedikides, C. (2001). The relationship between attitudinal ambivalence and desire to quit among college smokers. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31, 113–133. Lipkus, I. M., Kuchibhatla, M., McBride, C. M., Bosworth, H. B., Pollak, K. I., Siegler, I. C., et al. (2000). Relationships among breast cancer perceived absolute risk, comparative risk, and worries. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 9, 973–975. Lipkus, I. M., Pollak, K. I., McBride, C. M., Schwartz-Bloom, R. D., Lyna, P., & Bloom, P. S. (2005). Assessing attitudinal ambivalence towards smoking and its association with desire to quit among teen smokers. Psychology and Health, 20, 373–388. Loewenstein, G. (2005). Hot-cold empathy gaps and medical decision making. Health Psychology, 24, S49–S56. Loewenstein, G. F., Weber, E. U., Hsee, C. K., & Welch, E. S. (2001). Risk as feelings. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 267–286. Luce, M. F. (1998). Choosing to avoid: Coping with negatively emotion-laden consumer decisions. Journal of Consumer Research, 24, 409–433. Luce, M. F., Payne, J. W., & Bettman, J. R. (2001). The impact of emotional tradeoff difficulty in decision behavior. In E. U. Weber, J. Baron, & G. Loomes (Eds.), Conflict and tradeoffs in decision-making (pp. 86–109). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Maio, G. R., Bell, D. W., & Esses, V. M. (1996). Ambivalence and persuasion: The processing of messages of immigrant groups. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 32, 513–536. McCaul, K. D., Branstetter, A. D., Schroeder, D. M., & Glasgow, R. E. (1996). What is the relationship between breast cancer risk and mammography screening? A meta-analytic review. Health Psychology, 15, 423–429. Millar, M. G., & Tesser, A. (1989). The effects of affective-cognitive consistency and thought on the attitude-behavior relation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 189–202. Montague, R. P., & Berns, G. S. (2002). Neural economics and the biological substrates of valuation. Neuron, 36, 265–284. Nabi, R. L. (2003). Exploring the framing effects of emotion: Do discrete emotions differentially influence information accessibility, information seeking, and policy preference? Communication Research, 30, 224–247. Oatley, K., & Jenkins, J. M. (1996). Understanding emotions. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. S160 Journal of Communication 56 (2006) S140–S162 ª 2006 International Communication Association E. Peters et al. The Functions of Affect Osgood, C. E., Suci, G. J., & Tannenbaum, P. H. (1957). The measurement of meaning. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois. Parascandola, M., Hawkins, J., & Danis, M. (2002). Patient autonomy and the challenge of clinical uncertainty. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal, 12, 245–264. Payne, J. W., Bettman, J. R., & Johnson, E. J. (1993). The adaptive decision maker. New York: Cambridge University Press. Payne, J. W., Bettman, J. R., & Schkade, D. A. (1999). Measuring constructed preferences: Towards a building code. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 19, 243–270. Peters, E. (in press). The functions of affect in the construction of preferences. In S. Lichtenstein & P. Slovic (Eds.), The construction of preference. New York: Cambridge University Press. Peters, E., Burraston, B., & Mertz, C. K. (2004). An emotion-based model of stigma susceptibility: Appraisals, affective reactivity, and worldviews in the generation of a stigma response. Risk Analysis, 24, 1349–1367. Peters, E., & Slovic, P. (1996). The role of affect and worldviews as orienting dispositions in the perception and acceptance of nuclear power. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 26, 1427–1453. Peters, E., Slovic, P., & Gregory, R. (2003). The role of affect in the WTA/WTP disparity. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 16, 309–330. Peters, E., Slovic, P., & Hibbard, J. (2004). Evaluability manipulations influence the construction of choices among health plans (Report No. 04-02). Eugene, OR: Decision Research. Peters, E., Slovic, P., Hibbard, J., & Tusler, M. (2006). Why worry? Perceived risk of medical errors and willingness to act to reduce errors. Health Psychology, 25, 144–152. Peters, E., Västfjäll, D., Slovic, P., Mertz, C. K., Mazzocco, K., & Dickert, S. (2006). Numeracy and decision making. Psychological Science, 17, 407–413. Petrie, K. J., & Weinman, J. A. (1997). Perceptions of health and illness: Current research and applications. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic. Petty, R. E., Barden, J., & Wheeler, S. C. (2002). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion: Health promotions that yield sustained behavioral change. In R. J. DiClemente, R. A. Crosby, & M. Kegler (Eds.), Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research (pp. 71–99). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Petty, R. E., DeSteno, D., & Rucker, D. D. (2001). The role of affect in attitude change. In J. P. Forgas (Ed.), Handbook of affect and social cognition (pp. 212–236). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Petty, R. E., & Wegener, D. T. (1993). Flexible correction processes in social judgment: Correcting for context-induced contrast. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 29, 137–165. Priester, J. R., & Petty, R. E. (1996). The gradual threshold model of ambivalence: Relating the positive and negative bases of attitudes to subjective ambivalence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 431–449. Revenson, T. A., & Pranikoff, J. R. (2005). A contextual approach to treatment decision making among breast cancer survivors. Health Psychology, 24, S93–S98. Rimer, B. K., Halabi, S., Skinner, C. S., Lipkus, I. M., Strigo, T. S., Kaplan, E. B., et al. (2002). Effects of a mammography decision-making intervention at 12 and 24 months. Preventive Medicine, 22, 247–257. Journal of Communication 56 (2006) S140–S162 ª 2006 International Communication Association S161 The Functions of Affect E. Peters et al. Rottenstreich, Y., & Hsee, C. K. (2001). Money, kisses, and electric shocks: On the affective psychology of risk. Psychological Science, 12, 185–190. Schwarz, N., & Clore, G. L. (1983). Mood, misattribution, and judgments of well-being: Information and directive functions of affective states. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 513–523. Schwarz, N., & Clore, G. L. (2003). Mood as information: 20 years later. Psychological Inquiry, 14, 294–301. Shiv, B., & Fedorikhin, A. (1999). Heart and mind in conflict: Interplay of affect and cognition in consumer decision making. Journal of Consumer Research, 26, 278–282. Slovic, P. (1995). The construction of preference. American Psychologist, 50, 364–371. Slovic, P., Finucane, M. L., Peters, E., & MacGregor, D. G. (2002). The affect heuristic. In T. Gilovich, D. Griffin, & D. Kahneman (Eds.), Heuristics and biases: The psychology of intuitive judgment (pp. 397–420). New York: Cambridge University Press. Steginga, S. K., & Occhipinti, S. (2004). The application of the heuristic-systematic processing model to treatment decision making about prostate cancer. Medical Decision Making, 24, 573–583. Sutton, S. R. (1982). Fear-arousing communications: A critical examination of theory and research. In J. R. Eiser (Ed.), Social psychology and behavioral medicine (pp. 303–337). London: Wiley. Trafimow, D., & Sheeran, P. (2004). A theory about the translation of cognition into affect and behavior. In G. Maio & G. Haddock (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives in the psychology of attitudes: The Cardiff symposium (pp. 57–75). London: Psychology Press. Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1981). The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science, 211, 453–458. Watson, M., Lloyd, S., Davidson, J., Meyer, L., Eeles, R., Ebbs, S., et al. (1999). The impact of genetic counseling on risk perception and mental health in women with a family history of breast cancer. British Journal of Cancer, 79, 868–874. Weber, E. U., Baron, J., & Loomes, G. (2001). Conflict and tradeoffs in decision-making. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Wegener, D. T., & Petty, R. E. (1997). The flexible correction model: The role of naive theories of bias correction. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 29, pp. 141–208). New York: Academic Press. Witte, K. (1998). Fear as motivator, fear as inhibitor: Using the extended parallel response model to explain fear appeal success and failures. In P. A. Anderson & L. K. Guerrero (Eds.), Handbook of communication and emotion: Research, theory, and contexts (pp. 424–451). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. Zajonc, R. B. (1980). Feeling and thinking: Preferences need no inferences. American Psychologist, 35, 151–175. S162 Journal of Communication 56 (2006) S140–S162 ª 2006 International Communication Association