Black and Minority Ethnic Survey

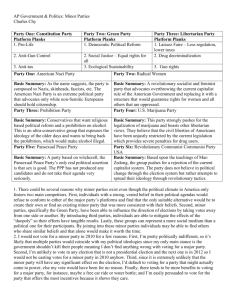

advertisement