Asset management

17 November 2014

Economist Insights

Hidden treasuries

Joshua McCallum

Head of Fixed Income Economics

UBS Global Asset Management

joshua.mccallum@ubs.com

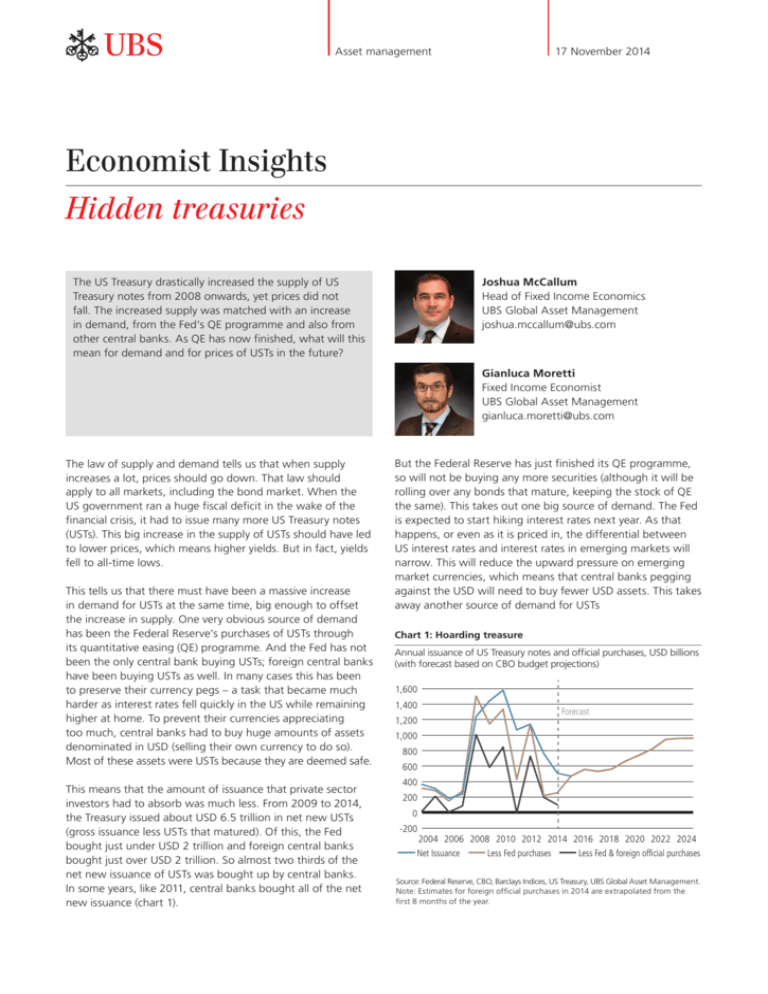

The US Treasury drastically increased the supply of US

Treasury notes from 2008 onwards, yet prices did not

fall. The increased supply was matched with an increase

in demand, from the Fed’s QE programme and also from

other central banks. As QE has now finished, what will this

mean for demand and for prices of USTs in the future?

Gianluca Moretti

Fixed Income Economist

UBS Global Asset Management

gianluca.moretti@ubs.com

The law of supply and demand tells us that when supply

increases a lot, prices should go down. That law should

apply to all markets, including the bond market. When the

US government ran a huge fiscal deficit in the wake of the

financial crisis, it had to issue many more US Treasury notes

(USTs). This big increase in the supply of USTs should have led

to lower prices, which means higher yields. But in fact, yields

fell to all-time lows.

This tells us that there must have been a massive increase

in demand for USTs at the same time, big enough to offset

the increase in supply. One very obvious source of demand

has been the Federal Reserve’s purchases of USTs through

its quantitative easing (QE) programme. And the Fed has not

been the only central bank buying USTs; foreign central banks

have been buying USTs as well. In many cases this has been

to preserve their currency pegs – a task that became much

harder as interest rates fell quickly in the US while remaining

higher at home. To prevent their currencies appreciating

too much, central banks had to buy huge amounts of assets

denominated in USD (selling their own currency to do so).

Most of these assets were USTs because they are deemed safe.

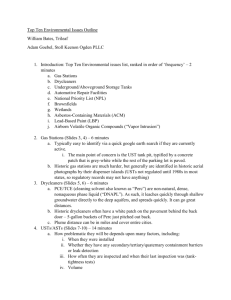

This means that the amount of issuance that private sector

investors had to absorb was much less. From 2009 to 2014,

the Treasury issued about USD 6.5 trillion in net new USTs

(gross issuance less USTs that matured). Of this, the Fed

bought just under USD 2 trillion and foreign central banks

bought just over USD 2 trillion. So almost two thirds of the

net new issuance of USTs was bought up by central banks.

In some years, like 2011, central banks bought all of the net

new issuance (chart 1).

But the Federal Reserve has just finished its QE programme,

so will not be buying any more securities (although it will be

rolling over any bonds that mature, keeping the stock of QE

the same). This takes out one big source of demand. The Fed

is expected to start hiking interest rates next year. As that

happens, or even as it is priced in, the differential between

US interest rates and interest rates in emerging markets will

narrow. This will reduce the upward pressure on emerging

market currencies, which means that central banks pegging

against the USD will need to buy fewer USD assets. This takes

away another source of demand for USTs

Chart 1: Hoarding treasure

Annual issuance of US Treasury notes and official purchases, USD billions

(with forecast based on CBO budget projections)

1,600

1,400

1,200

Forecast

1,000

800

600

400

200

0

-200

2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018 2020 2022 2024

Net Issuance

Less Fed purchases

Less Fed & foreign official purchases

Source: Federal Reserve, CBO, Barclays Indices, US Treasury, UBS Global Asset Management.

Note: Estimates for foreign official purchases in 2014 are extrapolated from the

first 8 months of the year.

So two sources of demand have gone, but what will happen

to supply? According the Congressional Budget Office (CBO),

a bipartisan research body for the US Congress, the US budget

deficit is going to reach its lowest level next year but will

start to rise thereafter. This increase is based upon current

legislation; the government could change its plans leading to a

lower (or even higher) deficit. Drastic changes look unlikely, so

the Treasury will probably be issuing more USTs in the future at

the same time as official demand shrinks.

If there is now going to be a big supply and demand

mismatch, does this mean that UST prices must fall and

push bond yields up? In the very short term (days or weeks),

mismatches between supply and demand can move UST

yields around. But longer term the effect is much smaller

because USTs are substitutes for other assets. If the price of

USTs falls enough, they start to look more attractive relative

to other riskier assets. Investors will sell those riskier assets

and buy USTs instead. Demand switches over from those

other assets into USTs.

Before the financial crisis, USTs made up about 25% of the US

bond market (chart 2). When government debt rose, the share

increased to about 40%. When the official sector holdings are

stripped out, the figures are more like 15% increasing to 23%,

a significantly smaller proportion initially and a significantly

smaller increase as well. But the thing about QE is that the

Fed creates new money to buy the bonds, so the investors

who sold their USTs end up with newly created cash in their

account. This is then used to buy other assets, which puts

downward pressure on the yields of those assets.

So what actually determines the price of USTs in the longer

run? Quite simply the price of the truly safe asset: the

overnight Fed Funds market. UST prices should be linked to

the expected path of the Fed funds rate (plus a risk premium

for the chance that the expectations are wrong), pretty much

regardless of supply and demand. The effect of increased

supply (net of purchases) is more likely to be felt in other,

riskier assets. But from here onwards, anyone who has been

hunting for treasuries for their portfolio should find them in

more plentiful supply.

Chart 2: Sharing the treasure

Treasuries as a share of US bond market, by face value

50

40

30

20

10

0

2004

Treasuries

2006

2008

Less Fed purchases

2010

2012

2014

Less Fed & foreign official purchases

Source: Bank of America/Merrill Lynch indices, Federal Reserve, US Treasury, UBS Global

Asset Management. Note: Bond market is defined as total of US high grade, US high

yield and US inflation linked markets. Fed and official purchases are deducted from

both the numerator and denominator.

The views expressed are as of November 2014 and are a general guide to the views of UBS Global Asset Management. This document does not replace portfolio

and fund-specific materials. Commentary is at a macro or strategy level and is not with reference to any registered or other mutual fund. This document is

intended for limited distribution to the clients and associates of UBS Global Asset Management. Use or distribution by any other person is prohibited. Copying any part of this

publication without the written permission of UBS Global Asset Management is prohibited. Care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of its content but no responsibility

is accepted for any errors or omissions herein. Please note that past performance is not a guide to the future. Potential for profit is accompanied by the possibility of loss.

The value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and investors may not get back the original amount invested. This document is a marketing

communication. Any market or investment views expressed are not intended to be investment research. The document has not been prepared in line with the requirements

of any jurisdiction designed to promote the independence of investment research and is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination of investment

research. The information contained in this document does not constitute a distribution, nor should it be considered a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular

security or fund. The information and opinions contained in this document have been compiled or arrived at based upon information obtained from sources believed to

be reliable and in good faith. All such information and opinions are subject to change without notice. A number of the comments in this document are based on current

expectations and are considered “forward-looking statements”. Actual future results, however, may prove to be different from expectations. The opinions expressed are

a reflection of UBS Global Asset Management’s best judgment at the time this document is compiled and any obligation to update or alter forward-looking statements as

a result of new information, future events, or otherwise is disclaimed. Furthermore, these views are not intended to predict or guarantee the future performance of any

individual security, asset class, markets generally, nor are they intended to predict the future performance of any UBS Global Asset Management account, portfolio or fund.

© UBS 2014. The key symbol and UBS are among the registered and unregistered trademarks of UBS. All rights reserved.

24152