Should I stay or should I go? The selectors' dilemma in post

advertisement

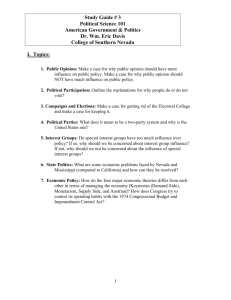

Should I stay or should I go? The selectors’ dilemma in post-primaries voting strategy in Italy Giulia Sandri, Université Catholique de Lille Antonella Seddone, University of Turin Paper for Presentation at the ESA Political Sociology Research Network Conference, University of Milan, 30th November & 1st December 2012 Work in progress 0 1. Parties, primary elections and primary voters Most recent literature that analyzes parties from an organizational perspective focuses often on the concepts of intra-party democracy and party organizational democratization (Scarrow, 1999; Scarrow and Kittilson, 2003; LeDuc, Niemi and Norris, 2002; Bosco and Morlino, 2007). Le Duc (2001) and Rahat and Hazan (2007) underline that the most used instrument for implementing this ‘democratization’ process is the enhancement of the inclusiveness of the methods for candidate and party leadership selection. The actors endowed with candidate and leader selection powers are the central actors in the functioning of the party according to many authors (Gallagher and Marsh 1988, Marsh 1993; Massari, 2004; Hazan and Rahat, 2010). At the moment, the most inclusive method identified by the literature for selecting candidates for elections or the party leader is represented by party primaries, i.e. internal direct elections by party members and (sometimes) supporters and voters (Cross and Blais, 2008 and 2009; Kenig, 2009). Although the literature on primaries is quite extensive, especially concerning the development of this instrument within the US political system (see, for example, Ranney, 1972; Norrander, 1989; Palmer, 1997; Morton and Gerber, 1998; Hopkin, 2001; Ware, 2002; Cohen et al., 2008) the analysis of the implementation of primary elections outside the US and in particular within the European context is not equally developed (Heidar and Saglie, 2003; Valbruzzi, 2005; Lisi, 2009; Wauters, 2009; Pasquino and Venturino, 2009 and 2010; De Luca and Venturino, 2010, Seddone and Venturino, 2011). Nevertheless, this instrument has been adopted by parties in several European countries such as, for example, Finland, Denmark, France, Spain, Greece and Italy (Laurent and Dolez, 2007; Lisi, 2009; Kenig, 2009; Mavrogordatos, 2005). Primary elections are a recurrent theme in the debate about parties and their organizational change (Gunther and Montero 2002; Wattemberg and Dalton 2000; Farrell and Webb 2000; Mair 1994; Panebianco 1982) and on the personalization of politics (Calise 2007, 2000; Poguntke and Webb 2007). Literature on party politics generally argues that primaries represent a further step in the organizational evolution of political parties. Katz e Mair (1993, 1994; 1995; 2002; 2009) argue that parties have progressively and strategically reduced the size of the “party on the ground”. The party in public office has taken over the organizational role of mass membership. Political parties seem to find new legitimacy in the participation in governments rather than in social integration and encapsulation: the result is a shift in the mobilizing dynamic of intra-party politics. In this perspective, political parties have changed their goals compared to the models of mass party theorized by Neumann (1956) and Duverger (1961). The model of parties as instruments of social integration has been reformulated within a new mobilizing strategy that goes beyond the traditional ideological boundaries (Kirchheimer, 1966). Trying to attract the median voter (Downs, 1956), political parties target their political message for all the electorate, adopting thus a catch-all approach. The old organizational structures, rooted in the grass-roots membership and ideologically distinctive, have been replaced by this new logic in the mobilization of party supporters. The 1 processes of party personalization and of professionalization in communication strategies have been long described by party literature and have become the surrogate of the old ideological party strength (Panebianco, 1982; Poguntke and Webb, 2005). This new tools for mobilizing voters may allow to attract new quotas of the electoral market, but do not guarantee a loyal and faithful electoral support (Dalton and Wattenberg, 2000), thus affecting negatively the transformation of voters into activists (Raniolo, 2004; 2006). Looking at declining membership data and election turnout (Scarrow, 2000; Scarrow, 1996), it seems that this new approach to electoral and party mobilization has entailed some problems in the effectiveness of these mobilizing strategies (Mair and van Biezen, 2001). Furthermore, the increasing diffusion of anti-party and anti-politics feelings among citizens and voters strengthen the idea of a emerging deep gap between parties and their supporters (Bardi, 1996; Poguntke, 1996; Poguntke and Scarrow, 1996; Scarrow, 1996). Primary elections can be considered as a tool used by parties in order to compensate the loss of legitimacy towards the electorate, to regain political credibility and to attract new supporters. Thus, parties are thought to provide more internal decision-making power to their grass-roots members and supporters as an incentive to their own membership to mobilize internally and to present a public image of being open and ‘democratic’ (Mair, 1994, Seyd, 1999; Scarrow, 1999; Scarrow, Webb and Farrell, 2000). Primaries represent a new pattern in the relationship between parties and their supporters. On the one hand, the adoption of internal direct elections contributes to incentive the internal mobilization of members already enrolled in the party, proposing new militant proceedings that in some way could represent a re-edition of the traditional mobilizing strategies of mass-based parties. On the other hand, primaries provide new opportunities for participation to those citizens less inclined to intra-party, traditional activism. In fact, the open and inclusive character of this instrument incentive new typologies of political participation, which do not require any formal affiliation to the party, but instead develop an intermittent participative behaviour that concerning in particular voters interested by cognitive mobilization (Dalton 2002; 1984). In this perspective of political economy of leadership and candidate selection methods, primaries are considered mainly as a tool used and promoted by parties with the specific goal of building a new relationship with supporters that is subsequent to their own catch-all electoral strategies. The effects of the adoption of primary elections on parties’ electoral dynamics are highly contested within the US literature on the subject. The debated question concerns the electoral gain in promoting primaries. Some scholars argue that there is a trade-off between the openness and inclusiveness of the candidate selection process and the electability of these candidates, but the question of the negative impact in electoral terms of these inclusive internal elections is still debated. The differences in the ideological positions of the general electorate and the primary selectorate are thought to explain the argued negative effects in electoral terms (Kaufmann et al., 2005; Norrander, 1989). The fact that the usually high 2 turnout in primary elections could trigger an increase in the electoral consensus for the party in general elections could be difficult to be valued by the general electorate (Adams and Merrill, 2008). Other studies focus on the negative stance and the aggressive discourse of primary campaigns. The mutual de-legitimization between primary candidates could disclose and emphasize internal conflicts and unsolved rivalries with damages to parties’ electoral performance: indeed, some supporters, after a negative campaign, could choose for defection in elections (Djupe and Peterson, 2002; Haines and Rhine, 1998; Peterson and Djupe 2005). Finally, other stances on this issue refer to the concept of divisiveness (Ware, 1979; Kenny and Rice, 1984; Kenney, 1988; Atkeson, 1998; Hogan, 2003; Johnson et al., 2010; Makse and Sokhey, 2010; Wichowsky and Niebler, 2010). Divisiveness in primary elections is thought thus to demotivate party members and supporters. Moreover, some authors have argued that primaries would weaken the mobilization potential of rank-and-file members by diminishing their power of control on the party leadership (Katz and Mair, 1995). Others have stressed that they would enhance participation of new supporters that are not traditionally interested in intra-party participation (Heidar and Saglie, 2003). Studies showed that (open) primaries could negatively affect the loyalty of candidates to the party, because the nomination is legitimated outside the latter and directly by primary voters (King 1999; Hansolabehere et al. 2001; Hopkins 2001). Indeed, primaries represent a new way for parties to distribute collective and selective incentives to members in order to foster their participation, although this new balance of incentives could change (or even damage) the relationship between grass-roots members and party leadership. In fact, party organizational change generates potential conflicts between traditional party delegates, activists and those with looser ties to the party. Including non-enrolled voters, supporters and sympathizers in the decision-making process could weaken affiliated members’ rights and privileges and thus the main incentives for their mobilization and involvement in party activities. In the long run, the use of primary elections could disincentive internal mobilization. In other words, primaries represent a participatory instrument characterized by low marginal costs, but with significant implications on party organizational structures and electoral performances. The idea is that divisiveness in primary elections could demotivate party members and supporters. In fact the high level of competitiveness could affect the electoral choices of the supporters of the losing candidate and even lead to their electoral defection. This paper focuses on the latter issue and particularly on the consequences of primary elections for selecting candidates for office. The main research question of this study, thus, is the following: how do selectors, namely primary voters, react to the defeat of their candidate in primary elections? Will they support the winning candidates at the following general elections? Or will they choose defection or abstention? The question appears to be relevant not only for understanding the dynamics of primary elections and their consequences on parties but also for analyzing the potential impact of this participatory instrument on 3 electoral behaviour in general elections. Our research question is therefore built on the literature on the political economy of candidate selection methods. We aim at exploring the consequences of the use of primaries for selecting candidates on parties and particularly on their electoral performance at subsequent elections as well as the potential disruptive impact of this instrument on party internal cohesion. 2. Hypotheses, data and methodology In order to address the main research question of this study, several aforementioned context factors could be taken into account, among which the most relevant are the ideological positioning and argued radicalism of primary voters and the degree of negativeness and divisiveness of primary elections campaigns. Given that in this paper we focus on the electoral behaviour and attitudes of the selectors, namely primary voters, we will develop our preliminary exploration of the main determinants of their voting strategies at subsequent elections on the basis of explanatory factors at individual level. Explanatory factors dealing with individual level features of primary voters will be thus taken into account. In particular, drawing on the US literature arguing that ideological extremism of primary voters impacts on party electoral gain (or rather loss) in subsequent general elections, this study identifies as main explanatory factors for accounting for voting strategies of primary voters the political profile and ideological positioning of the latter. The dependent variable of this study is thus represented by the attitudes of primary voters towards the party, and in particular by their voting strategy in subsequent elections. This variable is measured in a dichotomous way by looking at their declared intention to support any chosen candidate or rather to defect and abstain from voting for the party in general elections if the candidate they voted for in primary elections is not nominated. The main independent variable of this study is represented by the political profiles of primary voters, but in order to be exhaustive we also take into account more traditional variables such as the socio-demographic features of the selectors. Therefore, our main hypothesis is that loyalty or defection attitudes of selectors are determined primarily by their political profile. More specifically, we hypothesize that more ideologically radical selectors will choose more disruptive voting strategies in subsequent general elections, refusing to vote for any candidate but the one they supported in primary elections. The adoption of open primary elections for selecting candidates for office, by opening up the internal decision-making processes to simple supporters and party voters, not only could generate conflicts between traditional party delegates, activists and those with looser ties to the party, but also could impact negatively on parties’ electoral performance. This is because primary voters are generally considered to be more ideologically radical than the median voter and this extremism could also impact on their evaluation of the outcomes of primary elections and on their voting strategies at subsequent elections. More ideologically radical primary voters would be less 4 likely to support a different candidate in general elections than the one they voted for at primaries. The formulation of our assumptions and hypotheses are primarily linked to the empirical scope of this exploratory study. In order to assess our hypothesis, we rely on a case study. We focus on the case of primary elections for selecting mayoral candidates in Italy. Centre-left parties have organized primaries for selecting the party candidate for mayoral elections in several major and middle-sized cities in Italy since 2005. Up to now, more than 400 primaries have been organized since 2005 at local level for choosing the party candidate as mayor of the city in more than 70 cities. The “Candidate and Leader Selection” (C&LS) standing group of the Italian Political Science Association (http://www.candidateandleaderselection.eu/) has organized exit poll surveys during several of these mayoral primary elections in order to gauge the profiles, attitudes and behaviors of the selectors. All the primary elections surveyed have been organized by coalitions of centre-left parties and in most cases primaries have been promoted by the Partito Democratico (PD, “Democratic Party”), the main social-democratic party in Italy, and its electoral allies at national and local level (usually the main Italian radical post-communist left party, SEL “Left, Ecology and Freedom”, and either the small socialist party and/or the left-wing populist party M5S “Five Star Movement”). In total, 20 exit poll surveys have been realized in occasion of party primary elections held in several cities from 2005 to 2012. The size of the cities varies significantly, from very small ones (Oristano, 32.015 inhabitants) to very large ones (Milan, 1.348.769 inhabitants). Each survey is realized on the basis of a sampling of polling places set up by the organizing parties. Therefore, in order to develop a very preliminary exploration of the voting strategies of Italian primary voters at subsequent (mayoral) elections, we rely on survey data collected between 2007 and 2012 on selectors’ profiles, behaviors and attitudes. Consequently, the formulation of the main hypothesis of the study is primarily linked to the specific context of Italian politics. Although nowadays Italian political parties are overall delegitimized and their image is significantly undermined by widespread anti-party attitudes, they still exert a relevant influence in shaping voting behavior (Cotta and Verzichelli, 2007). Several scholars have assessed the increasing dissatisfaction and lack of political trust of Italian citizens (Cartocci, 2007) as well as the spreading of populism and anti-politics within society. Nevertheless, the influence of Italian parties in determining voting choices and political identity is still dominant (Bull and Newell, 2006; Mammone and Veltri, 2010). This phenomenon could be considered as a legacy of the strong Italian mass parties from which derived the current Italian political organizations. Widespread partisan identities and locally rooted party organizational structures are still a relevant feature of Italian politics (Bartle and Bellucci, 2008). This is mainly associated to the persistence of strong ideological ties to mainstream parties. The voting behaviour in Italy appears to be less volatile than in other EU member states and membership figures remain higher if compared to other European countries (Van Biezen et al., 2011). Current Italian parties’ societal reach, either in activism or electoral support terms, can thus be considered generally comparable to the social boundaries of old mass parties. In other words, despite a generalized party crisis in terms of internal 5 functioning and political trust, the traditional ideological bonds and partisan identification patterns appear to be quite resilient and still primarily determine electoral loyalties. In fact, during the First Republic, voting behaviour was characterized by strong party loyalty, due to widespread ideologization of the electorate and the presence of strong political subcultures - Christian democratic, Communist, Socialist, laic (Liberal and Republican), Neofascist and, up to the early 1950s, Monarchic. As far as dynamics of competition are concerned, the First Republic featured a sort of ‘blocked democracy’, with extremely partial alternation in office. This lead to the presence of territorially concentrated subcultures, namely the Communist one in the regions dominated by the PCI (the “red belt”: Tuscany, Emilia-Romagna and Umbria) and the Catholic one in the regions dominated by the DC (the “white belt”: Abruzzo, Basilicata and Veneto). Except for the fact that Berlusconi’s parties (Forza Italia, “Forward Italy” and later the People of Freedom) and the Northern League have taken over the political space vacated by the dissolution of the Christian democratic party in 1993, similar patterns of partisan identity and voting behaviour are still relevant today (Cotta and Verzichelli, 2007). The role of political culture, ideology and partisan identity in shaping electoral behaviour remain salient in contemporary Italian politics. Hence, our analysis aims at understanding which are the main features in terms of ideological positioning, political culture and more generally of political profile among the selectors. The aim is also to explore to what extent the variation in the selectors’ political profile could contribute in explaining the voting strategy they choose in subsequent (mayoral) elections. To what extent the political profile (and more specifically the ideological positioning) of primary voters do influence their choice of electoral loyalty (or defection) to the party in the event of the defeat of the candidate they support? What happen when the incentives associated with a specific candidate appeal fade away in subsequent elections? Would the primary voters choose loyalty to the party, supporting the selected candidate or would they choose defection (not voting for their party) or abstention in subsequent elections? Firstly, we hypothesize that loyalty attitudes in post-primary voting strategy are associated with a more structured ideological identity and a stronger relationship with the party. Thus, enrolled members and party supporters (namely selectors that have previously voted for the party) will remain loyal to their party regardless the result of primary elections and would therefore vote for any candidate selected through this instrument. Conversely, an attitude of defection would be mainly associated to a weaker relationship with the party, and thus with primary voters that are not party members or supporters and that in the event of the defeat of their preferred candidate could more easily opt for defection in subsequent elections. Secondly, more ideologically radical selectors will choose more disruptive voting strategies in subsequent general elections, refusing to vote for any candidate but the one they supported in primary elections. We use a dataset composed by data collected on the basis of 8 exit-poll realized during 8 primaries for selecting the mayoral candidate of the centre-left coalition and promoted by the Democratic Party. We have taken into account the exit poll data collected in a set of 6 comparable cities both in terms of size and social structure. We have retained only the 8 biggest cities from the whole Candidate and Leader Selection (C&LS) dataset for comparability reasons. Our dataset integrate a sample of around 16000 surveyed individuals. The core questionnaire focused on three dimensions: the socio-demographic profile of selectors, their political profile and their voting strategies in post-primary phase. The details concerning the survey sample and the dataset are presented in Table11. In particular, the dependent variable of this study, the selectors’ post-primary voting strategy, is operationalized on the basis of a specific item in the questionnaire. The question asked to the respondents was the following: “what will you do at local elections in case of defeat of you candidate?”. Six response categories were presented to the respondents: “I am sure my candidate will be selected”; “I will vote for any candidate of the Democratic Party even if he/she is not the one I am supporting now”; “I do not know, it depends on who will win the primaries”; “I will vote for another party”; “I do not know” and “I will not vote”. These response categories have then be recoded into a dichotomous variable: 1=loyalty attitude, considering all the selectors who declared their intention to support any candidate regardless the result of primary contest; and 0= defection attitude, that consider all the selectors which either were uncertain about their future voting strategy or showed a clear intention to vote for other candidates or parties. Therefore, in this paper we provide a very preliminary, exploratory account of the main determinates of the post-primary voting strategy of selectors and thus of their loyalty/defection attitudes. We explore also their socio-political profile and we try to determine the extent to which the matter impact on their voting strategies. After providing a brief descriptive account of the main dependent and independent variables, we will use an exploratory logistic regression in order to identify the main dimension that could influence these two attitudes. Give that this is a first, preliminary exploration of the survey data, the database has not been weighted yet. Table1. Survey design CITY GENOVA BOLOGNA CAGLIARI TORINO MILANO FIRENZE BOLOGNA GENOVA TOTAL YEAR 2012 2011 2011 2011 2011 2009 2009 2007 - SAMPLE (N) 3800 1085 2272 2175 1407 1722 1388 2270 16119 FRAME (N) 25090 28120 5629 53185 67499 37468 24920 35296 277207 COVERAGE (%) 15,1 3,9 40,4 4,1 2,1 4,6 5,6 6,4 5,8* Note: * = average value. For further details concerning the dataset, the questionnaire and the polling stations sampling procedure please visit the website of C&LS: http://www.candidateandleaderselection.eu/. 7 3. Profiling selectors In this paper we develop a preliminary assessment of the participatory dynamics entailed by primary elections in Italy. If it is true that the primary electorate differ significantly from the one mobilized in the general election (Pasquino and Venturino 2009; Kaufmann et al. 2003; Ranney and Epstein 1966) then it is particularly relevant to assess the nature and rationales of this variation. In fact, the differences in terms of socio-demographic and political profiles between the two electorates could impact on the type of candidates selected through primaries. Nevertheless, as underlined by Kaufmann et al. (2003) differences among “selectors”, namely primary voters, and general elections voters are not that wide in case of open primaries. Therefore, as primary elections for selecting the mayoral candidate in Italy are open to party members, supporters and in general to the whole electorate of the party promoting the consultation (PD or center-left coalition), we can expect that the socio-political profile of these selectors would not vary significantly with regard to the one of the general electorate of the center-left. Table 2 presents the data concerning the socio-demographic profile of primary voters and their voting strategy in subsequent elections. Gender represents the first indicator used to assess the profile of primary voters. From the data presented in Table 2 we can see that our sample is consistent with previous literature on primary elections in Italy. Male participation (51,7%) is higher than female one (48,3%). Nevertheless, the dependent variable of this study vary substantially on the basis of gender: among selectors choosing defection, 52,6% are women, conversely among loyalist men are the majority (53,7%). The variation of post-primary attitudes in terms of voters’ age is even stronger. Data reported in Table 2 show that primary elections indeed do mobilize different generational cohorts. A quick overview of the table shows a prevalence of older voters not only in the general sample but particularly among those selectors that remain loyal to their party. 8 Table 2. Contingency table: socio-demographic profile and voting strategy Age* 16-24 25-34 35-44 45-64 >65 N Gender* Female Male N Defection (%) 11,7 14,0 20,0 26,7 27,7 4034 Elementary Junior High School Education* High School Higher Education N Manager, judge, university professor Entrepreneur Self-employed/Business owner Professional (doctor, lawyer, etc.) Teacher Employee Professional Worker Status* Temporary worker Retired Unemployed Housewife Student Other N Never 2-3 times per year Religious 1 time per month practice** 2-3 times per month Every week N Loyalty (%) Total 7,1 8,7 11,7 12,6 15,2 16,9 36,1 32,7 29,9 29,1 7340 11374 52,6 47,4 5090 46,3 53,7 10762 48,3 51,7 15852 6,8 16,5 35,7 40,9 5133 6,1 2,1 3,8 11,1 12,0 16,0 4,4 1,6 22,4 2,9 4,2 9,9 3,6 4588 54,9 16,3 5,6 6,9 16,3 3466 10,3 18,5 36,8 34,4 10868 5,6 1,3 2,7 9,0 9,3 14,5 3,4 1,1 37,7 1,8 4,6 5,5 3,4 9218 55,0 17,6 5,7 5,7 16,1 7164 9,2 17,9 36,5 36,5 16001 5,8 1,6 3,1 9,7 10,2 15,0 3,8 1,2 32,6 2,2 4,4 7,0 3,5 13806 55,0 17,2 5,7 6,1 16,1 10630 Note. * = p <0.01; * = p = 0.089. In fact, if we look at the differences between the two electoral strategies, we notice that among loyalists there is an higher proportion of older selectors (66%) and this data could be explained by looking at the professional status. One third of the sample is composed by retired citizens. In Italy, older supporters tend to mobilize more in primary elections than younger voters. Primaries, and in general any type of open and inclusive consultation, represent a strategy promoted by parties to broaden their societal reach and to interact with their base in order to compensate the weaker legitimacy triggered by anti-party feelings (Bardi 1996; Poguntke 1996; Poguntke and Scarrow 1996). In other words, through the claim 9 of internal democratization parties try to strengthen (or to mend) the relationship with their members and voters. Primaries appear thus to renew the traditional pattern of participation typically associated with mass party organizations, deeply rooted within Italian society and territory. Even if open primaries’ aim is to mobilize less active supporters and sympathizers, those that have weaker ties to party organization and that are less inclined to intraparty activism, this kind of elections appears to be mobilizing mainly elderly voters. The older selectors are more used to the forms of political participation promoted by parties than younger voters, usually more apathetic with respect to conventional forms of political participation. Another indicator that has to be considered in order to understand the dynamics of participation in primary elections is the voters’ educational attainment. The data reported in Table 2 show quite significant differences with regard to this variable. Considering the general sample, we can see that almost 73% of selectors have a high school diploma. Moreover, among “defectionists” there is a significantly higher proportion of college graduates (40,9%). Those selectors are thus usually more oriented towards cognitive mobilization than towards more traditional and structured form of political activism. These are citizens highly interested in politics but not directly engaging in traditional forms of political activism. Therefore, it appears rather logical that, in case of defeat of their candidate, the strategy they adopt is to not be involved further in intra-party decision-making and activities nor to support the party candidate (that they did not previously supported) in general elections. Finally, the religious element seem to be irrelevant with regarding to post-primaries choices: the majority of the sample (55%) never attends religious practice while no relevant variation between defectionists and loyalist emerge with regard to this variable. Table 3 presents the data concerning the political profile of the surveyed selectors. It is interesting to note that 76,4% of the selectors have already participated to a primary election (“Veterans”, while “Newcomers” are those voting for the first time in primary elections). If we take into account the selectors’ post-primaries strategies, we can see that “Veterans” show more loyal attitudes (82,5%) than those participating in primary elections for the first time. Electoral behavior in general election appears not to vary significantly according to the ideological positioning (self-placement) of the respondents. Unsurprisingly, we can see that the sample is composed by a wide proportion of not enrolled citizens (78,6%), while selectors formally enrolled in parties are less than a quarter of the sample (21,3%). Political activism seems to be relevant in influencing loyalty or defection strategies in general elections. Among loyalist, the proportion of enrolled members rises to 26%, with a variation of more than 5 percentage points from the general sample. Conversely, the proportion of non-members is significantly higher among “defectionists” (87,2%), with a variation of slightly less than 10 percentage points to the general sample. Conversely, if we look at the post-primary strategies of the supporters of the parties promoting primary elections– that is, those selectors that have previous voted for this given party in general elections- the situation is less clear. There is a higher proportion of PD supporters (65,5%) in the general sample, who represent also the 10 most relevant group among loyalist (70,1%). Indeed, 39,5% of “defectionists” are voters supporting other left-wing parties than PD. Table3. Contingency table: political profile and voting strategy Defection(%) Loyalty(%) Total 82,5 76,4 63,1 36,9 17,4 23,6 4925 10647 15572 Previous participation to primary elections* Veterans Newcomers N Ideological selfplacement* (1-5) Left Center-left Center Center-right Right N 48,2 38,6 9,8 2,3 1,0 4476 51,9 43,5 4,2 ,3 ,1 9179 50,7 41,9 6,0 1,0 ,4 13655 Party Activism* Not enrolled PD member Left-wing party member Right-wing party member N 87,2 9,2 3,4 0,2 5151 74,6 22,3 3,2 ,0 10893 78,6 18,1 3,2 ,1 16044 Party Supporter* PD voter Left-wing party voter Abstention– Blank Ballot N 55,1 39,5 5,4 4298 70,1 28,4 1,5 9978 65,6 31,7 2,7 14276 Note. * = p <0.01. 4. The main determinants of selectors’ voting strategy in subsequent elections In order to explore the strength of the argued association between the political profile of selectors and their loyal attitudes towards the party promoting primaries in the following local elections we have simply analyzed how the two sets of variables correlates. Table 4 summarizes the correlation coefficients between post-primary strategies and socio-political variables. Orientation towards defection or loyalty – in the hypothesis of defeat of the supported primary candidate - appears to be significantly related to gender, age, and educational level, previous experience in primary voting, ideological position, political activism and electoral support to center–left parties in general elections. 11 Table 4. Correlation matrix between voting strategy, socio-demographic profile and political profile Voting strategy Gender Education Professional Status Religious practice Prev. participation Age R-L Self-placement Party Activism Party Supporter (1) (2) (3) 1 ,059** -,076** ,006 -,009 ,213** ,104** -,109** 1 -,046** ,007 -,082** ,021** -,058** ,019* 1 -,163** -,041** ,082** -,073** ,017* ,112** ,103** -,162** ,012 (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) -,022* -,005 -,004 1 -,033** ,062** ,233** 1 -,162** ,111** 1 -,075** 1 -,053** ,020* -,058** -,108** ,010 -,041** -,055** ,268** ,009 -,151** -,060** ,065** (10) 1 ,034** 1 -,020* Note. ** = p <0.01; * = p <0.05. In order to develop further our analysis of the association between primary voters’ political profile and their voting strategy in subsequent elections, we have also run an exploratory logistic regression. This is a preliminary exploration of the main determinants of their voting strategies at subsequent elections on the basis of explanatory factors at individual level. Therefore, the data have been also modeled with logistic regressions in order to assess whether our predictor variables significantly predicted whether or not a primary will develop loyalty attitudes towards the party in subsequent elections2. For developing our exploratory analysis, we relied on two hypotheses. Firstly, we hypothesized that loyalty attitudes in postprimary voting strategy are associated with a more structured ideological identity and a stronger relationship with the party. Secondly, we argued that more ideologically radical selectors will choose more disruptive voting strategies in subsequent general elections, refusing to vote for any candidate but the one they supported in primary elections. The logistic regression, although performed on unweighted data and for exploratory reasons, could contribute in clarifying to what extent our preliminary hypotheses are supported by the data. 2 In order to simplify the interpretation of the logistic model’s outcomes, we have recoded some of the independent variables into additive scales. The professional status has been recoded into a “social class” variable based on four categories: upper class (manager, judge, entrepreneur, self-employed, professional); middle class (employee, teacher); lower class (worker, temporary worker) and inactive citizens (all the other categories). The latter is taken as reference category in the analysis, as it is also the case for the category “male” for the gender variable, the category “>65” for the age variable, the category “higher education” for the education variable, the category “every week” for the religious practice variable; the category “newcomers“ for the participation variable; the category “right“ for ideological positioning; the category “Abstention– Blank Ballot “ for the electoral support variable; and the category “Right-wing party member “ for the activism variable. 12 1 The results are reported in Table 5. Among socio-demographic variables, only age and gender seem to exert a statistically significant impact, with male and older selectors being more likely to remain loyal to the party in subsequent elections even if their chosen candidate loses the primary contest. Moreover, the data presented in Table 5 seem to support our hypothesis of the significant impact of the individual political profile on the voting strategies of selectors. Unsurprisingly, political identity is the most relevant dimension for explaining the choice of a more or less loyal attitude in general elections. All political variables are statistically significant and contribute in in explaining the adoption by primary voters of a loyal attitude towards the party disregarding the outcomes of primary competition. As expected, the selectors’ political profile indeed matters in shaping their voting choices in general elections. Being a party member, having some previous participatory experience in primaries, being a supporter of the party or of the center-left coalition seems to be political features of individual selectors that incentive more loyal attitudes in general elections. For instance, in Table 5 we can see that the odds of scoring 1 (=loyalty attitudes) have increased by a factor of 1.5 having increased the level of previous experience in participatory instruments by one unit (from newcomers=0 to veterans=1). The same goes for the ideological positioning: a one unit increase in the predictor (ideological L-R scale ranging from 1 to 5, where 5 represent right positions and 1 left ones) triggers a decrease in the odds of being loyal to the party of a factor of 0.3. Here too, enrolled members of the Democratic Party or of one of the other parties of the center-left coalitions are way more likely to be loyal to the party even if their candidate is not selected as a result of primary elections. Moreover, as expected, the fact of having previously voted for the party or the coalition promoting primary elections is directly related to post-primary voting strategies: being a Democratic Party supporter increases the odds of remaining loyal to the party by a factor of 2.5, and the exponentiation of regression estimate is also significant. In conclusion, loyalty attitudes in post-primary voting strategy are indeed associated with a stronger relationship with the party. On the contrary, more ideologically radical, left-wing selectors seem not to be more likely to choose more disruptive voting strategies in subsequent general elections, but rather support whatever candidate is selected by the primary competition. 13 Table 5. Logistic regression: impact of socio-demographic profile and political profile on voting strategy B GENDER Female AGE 16-24 25-34 35-44 45-64 EDUCATION Elementary Junior High School High School PROFESSIONAL STATUS Upper class Middle class Working class RELIGIOUS PRACTICE Never 2-3 times per year 1 time per month 2-3 times per month L-R SELF-PLACEMENT Left Center-Left Center Center-Right PREV. PARTICIPATION Veterans ACTIVISM Not Member DP’s Member Left wing party’s Member PARTY SUPPORTER PD voter Left-wing party voter Constant S.E. -,309 Sig. ,061 Exp(B) ,000 ,734 0,000 -,360 -,189 -,327 ,087 ,137 ,102 ,087 ,079 -,227 -,100 ,066 ,235 ,109 ,067 -,190 -,124 -,105 ,092 ,085 ,129 ,026 ,034 ,278 -,149 ,092 ,108 ,153 ,143 1,148 1,116 ,201 -,951 ,574 ,574 ,584 ,688 ,440 ,068 ,008 ,065 ,000 ,269 ,697 ,828 ,721 1,091 0,214 ,334 ,358 ,321 ,797 ,905 1,069 0,257 ,039 ,143 ,415 ,827 ,884 ,900 0,194 ,776 ,755 ,070 ,298 1,026 1,034 1,320 ,862 0,000 ,045 ,052 ,730 ,167 3,153 3,052 1,223 ,386 ,000 1,553 0,000 2,173 2,902 2,756 1,161 1,164 1,171 ,934 ,237 -3,332 ,153 ,156 1,292 ,061 ,013 ,019 8,781 18,207 15,739 0,000 -2 Log likelihood ,000 ,128 ,010 2,546 1,268 ,036 6863,245a Further empirical support to our hypotheses is also provided by the detailed analysis of the motivations that shaped selectors’ voting choices in primary elections. In the questionnaire presented to the respondents, a question was in fact asked concerning the reasons for choosing a specific candidate in primary elections. A total of 8 response categories were presented to the respondents and the frequencies and label of each category are reported in Figure 1. Figure 1 shows that the personal appeal of the individual candidate is one of the most relevant rationales at the basis of the selectors’ preferences. The second most important 14 motivation for choosing a primary candidate is the political programme proposed by the candidate. Moreover, we can see from Figure 1 that the respondents adopting loyal attitudes in subsequent elections declare to have chosen their candidate mainly on the basis of his/her specific profile, but a significant proportion (almost 30%) of respondents declares to have taken into account the political proposal of the candidate and the fact that the latter is closer to own political and partisan identity. This shows that there is a relevant relationship between voting strategy in general elections, the primary voters’ political profile and his/her motivations. The political stances of primary voters appear to be as relevant as the evaluation of the personal profile and career of individual candidates in primary elections. Figure 1. Motivations for candidate choice Conclusions The raw data and exploratory analyses presented in this study focused on the political attitudes towards the party of primary voters and particularly their loyalty in terms of electoral behavior. This study aimed at assessing the hypothesis generally developed by the literature on the American case of the negative impact of primary elections on parties in 15 electoral terms. This study also focused on a specific case study, namely primary elections organized for selecting the candidates for mayoral office of the center-left coalition in major Italian cities between 2007 and 2012. These primaries were overall promoted by the Democratic Party. The study is based on an original dataset composed by survey data on a sample of more than 16000 individuals. The very preliminary exploration developed in this draft version of the paper shows that selectors, namely primary voters, elaborate their voting strategies in subsequent elections (in this case, the local elections for selecting the mayor) mainly on the basis of their relationship with the party that promoted the consultation. One of the main determinants of their voting strategy in subsequent elections, and thus of there is indeed their political profile and particularly their ideological positioning and their degree of political activism. Selectors formally affiliated to the party promoting the primary elections are unsurprisingly more loyal to their party than unaffiliated voters, but also simple supporters tend to be less likely to defect than other citizens. Although not surprising and quite logical, this empirical evidence seems to show that parties indeed do matter nowadays. Literature on primary elections in Europe seem to suggest that this instrument of intra-party democracy is bound to led parties to an organizational decline by broadening excessively their societal reach and bringing conflict at their core by opposing ordinary members’ to supporters with weaker organizational ties to the party. Our preliminary analysis seems to support, on the contrary, the idea that primary elections do not undermine the organizational dimension of parties but rather trigger the development of a new form of relationship between parties, supporters and voters. References Adams, J. and Merrill, S., Candidate and party strategies in two-stage election beginning with a primary, in «American Journal of Political Science», LII, 2, 2008, pp. 344-359. Atkeson, L. R., Divisive Primaries and General Election Outcomes: Another Look at Presidential Campaigns, «American Journal of Political Science», XLII, 1998, pp. 256-71. Born, R., The Influence of House Primary Election Divisiveness on General Election Margins, 1962-1976, «The Journal of Politics», LXIII, 1981, pp. 640-61. Cohen, Marty, Hans Noel, and John Zaller, The Party Decides: Presidential Nominations Before and After the reform, Chicago, UCP, 2008. Cross, W.; Blais A., Who selects the party leader?, «Party Politics», 2012, vol. 18, no.2, pp. 127-150. Dalton R.J., Citizen Politics: Public Opinion and Political Parties in Advanced Industrial Democracies, Chatham, Chatham House Publications, 2002. Dalton, R.J. and Wattenberg M.P. (eds), Parties Without Partisans. Political Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2000. De Luca, R. and Venturino, F. (eds.), Mobilitazione e partecipazione elettorale. Un’analisi delle ‘primarie’ per l’elezione del primo segretario del PD, Roma, Aracne, 2010. 16 Djupe, P.A. and Peterson, A.M., The impact of negative campaigning. Evidence from the 1998 senatorial primaries, in «Political Research Quarterly», LV, 4, 2002, pp. 845-860. Faucher-King, F. La modernisation du parti travailliste, 1994-2007. Succès et difficultés de l’importation du modèle entrepreneurial dans un parti politique, Politix, 2008, 21(81), pp. 125-149. Fusaro, C., Elezioni primarie: prime esperienze e profili costituzionali, «Quaderni dell’Osservatorio Elettorale», 2006, no. 55, pp. 41-62. Haynes A.A., Flowers J.F. and Gurian P., Getting the Message Out: Candidate Communication Strategy During the Invisible Primary in «Political Research Quarterly», September 2002, vol. LV, no. 3, pp. 633652. Hazan R.Y. and Rahat G., Democracy within parties, Oxford University Press, 2010. Hazan R., Rahat G. (2006). Candidate Selection, in Handbook of Party Politics. Edited by Richard S. Katz and William Crotty, Sage, London, 2006. Hopkin, J., Bringing the members back in? Democratizing candidate selection in Britain and Spain, in «Party Politics», VII, 2001, pp. 343-361. Johnson, G.B., Petersheim, Meredith-Joy and Wasson and Jesse T. Divisive Primaries and Incumbent General Election Performance:Prospects and Costs in U.S. House Races, «American Politics Research», XXXVIII, 2010, pp. 931–955. Katz, R.S. and Mair, P., Changing models of party organization and party democracy. The emergence of the Cartel Party, in «Party Politics», I, 1995, pp. 5-28. Kaufmann, K.M., Gimpel, J.G. and Hoffman, A.H., A promise fulfilled? Open primaries and representation, in «Journal of politics», LXV, 2, 2003, pp. 457-476. Kenig, O., Democratization of party leadership selection: do wider selectorates produce more competitive contests?, «Electoral Studies», XXVIII, 2009, pp. 240–247. Kenney, P. J., Sorting Out the Effects of Primary Divisiveness in Congressional and Senatorial Elections, «Western Political Quarterly», XLI, 1988, pp. 765-77. LeDuc, L., Democratizing party leadership selection, in «Party politics», VII, 3, 2001, pp. 323-341. LeDuc, L., Niemi, R.G. and Norris, P. (eds.), Comparing democracies 2: new challenges in the study of elections and voting, London, Sage Publications Ltd, 2002. Lefebvre, R. Les primaires socialistes : La fin du parti militant. Paris: Raisons d'agir, 2011. Lisi, M., The Democratization of Party Leadership Selection in Comparative Perspective, Paper prepared for presentation at the ECPR general conference, Potsdam 10-12 September 2009. Makse, T. and Sokhey Anand E. Revisiting the Divisive Primary Hypothesis: 2008 and the Clinton−Obama Nomination Battle, «American Politics Research», XXXVIII, 2010, pp. 233-265. Mair, P., Party Organizations: From Civil Society to the State, in R.S. Katz e P. Mair, How Parties Organize, Sage Publications Ltd, 1994, pp. 1-22. Norrander, B., Ideological representativeness of presidential primary voters, in «American Journal of Political Science», XXXIII, 3, 1989, pp. 570-587. Niemi, R. G., Craig S., Mattei F. Measuring Internal Political Efficacy in the 1988 National Election Study, “American Political Science Review”, vol. 85, 1991, pp. 1407-13. Palmer, N., The New Hampshire Primary and the American electoral process, Praeger, Westport, Connecticut, 1997. Pasquino, G., Conclusioni, in Pasquino, G. and Venturino, F. (eds.), Le primarie comunali in Italia, Bologna, Il Mulino, 2009, pp. 241-266. 17 Pasquino, G. and Venturino, F. (eds.), Il Partito Democratico di Bersani. Persone, profili e prospettive, Bologna, Bononia University Press, 2010. Pasquino, G. and Venturino, F. (eds.), Le primarie comunali in Italia, Bologna, Il Mulino, 2009. Peterson, D. A. and Djupe, P. A., When Primary Campaigns Go Negative: The Determinants of Campaign Negativity, «Political Research Quarterly», LVIII, 2005, pp. 45-54. Piereson, J. E. and Smith, T. B., Primary Divisiveness and General Election Success: A Re-Examination, «The Journal of Politics», XXXVII, 1975, pp. 555-62. Quinn, T. Electing the Leader: the British Labour Party’s Electoral College, “British Journal of Politics and International Relations”, 2004, Vol. 6, pp. 333-352. Rahat, G., Hazan, R. Candidate Selection, in Richard Katz and William Crotty (eds), Handbook of Party Politics, London, Sage, 2006, pp. 109-121. Rahat, G. and Hazan, R. , Participation in Party Primaries: Increase in Quantity, Decrease in Quality, in T. Zittel and D. Fuchs (eds), Participatory Democracy and Political Participation. Can Participatory Engineering Bring Citizens Back In?, Routledge, ECPR Studies in European Political Science Series, 2007, pp. 57-72. Ranney A., Turnout and Representation in Presidential Primary Elections, «American Political Science Review», LXVI, 1972, pp.21-37. Ranney, A. Candidate Selection. In David Butler, Howard R. Penniman, and Austin Ranney (eds.), Democracy at the Polls. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute, 1981, p. 84-102. Rapoport, R.; McGlennon, J.; Abramowitz, A. The Life of the parties: Activists in presidential politics, 1986, Lexington, University of Kentucky Press. Russell, M. Building New Labour: the Politics of Party Organization. New York: Palgrave, 2005. Sartori, G. Concept Misformation in Comparative Politics, "American Political Science Review”, vol. 4, 1970, pp. 1033-53. Scarrow S., Webb P. and Farrell D., From social integration to electoral contestation, in R. Dalton e M.P. Wattenberg (eds.), Parties without Partisans, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2000, pp.129-153. Scarrow, S., Parties and the expansion of direct democracy. Who benefits?, «Party Politics», V, 1999, pp. 341-362. Seyd P., New parties. New politics? A case study of the British Labour Party, in «Party Politcs», V, 1999, pp. 383-405. Stone, Walter, Ron Rapoport and Monique Schneider (2004). Party Members in a Three-Party Election: Major Party and Reform Activism in the 1996 American Presidential Election. Party Politics, vol 10, no. 4, pp. 445-469. Valbruzzi, M., Primarie. Partecipazione e leadership, Bononia University Press, Bologna, 2005. Ware A., The American direct primary: party institutionalization and transformation in the North, Cambridge University Press, 2002. Ware, A., “Divisive” primaries. The important questions, in «British Journal of Political Science», IX, 3, 1979, pp. 381-384. Wattenberg, M. P. The Rise of Candidate-Centered Politics: Presidential Elections of the 1980's, Harvard University Press, 1991. Wichowsky, A. and Niebler, S. E., Narrow Victories and Hard Games: Revisiting the Primary Divisiveness Hypothesis, «American Politics Research», XXXVIII, 2010, pp. 1052–1071. 18