Retailing and Wholesaling: Textbook Chapter

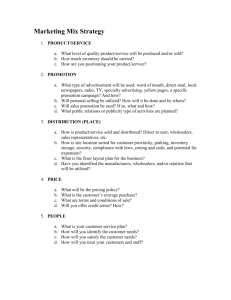

advertisement