Canada: Financial System Stability Assessment - Update

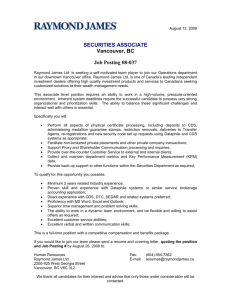

advertisement