competitive strategies in the us retail industry

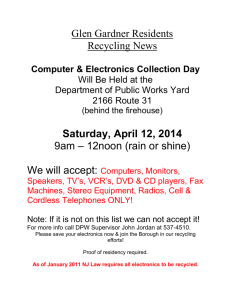

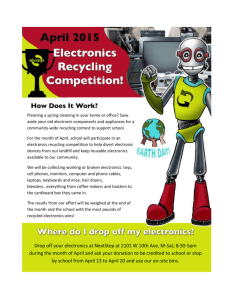

advertisement