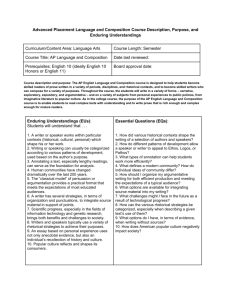

english language and composition

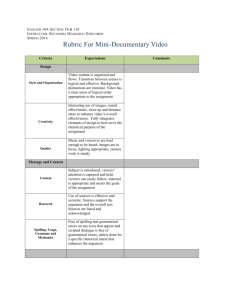

advertisement