JAN

THEORETICAL PAPER

Postoperative recovery: a concept analysis

Renée Allvin1, Katarina Berg2, Ewa Idvall3 & Ulrica Nilsson4

Accepted for publication 11 October 2006

1

Renée Allvin MSci RNA

Doctoral Student

Department of Anaesthesiology and Intensive

Care, Örebro University Hospital and

Department of Clinical Medicine, Örebro

University, Örebro, Sweden

2

Katarina Berg MSci RNA

Doctoral Student

Department of Medicine and Care,

Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden

3

Ewa Idvall PhD RNT

Associate Professor

Scientific Tutor and Senior Lecturer, Research

Section, Kalmar County Council, Kalmar and

Department of Medicine and Care, Linköping

University, Linköping, Sweden

4

Ulrica Nilsson PhD RNA

Senior Lecturer

Department of Anaesthesiology and Intensive

Care, Örebro University Hospital and

Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery,

Örebro University Hospital and Department

of Health Sciences, Örebro University,

Örebro, Sweden

Correspondence to Ewa Idvall:

e-mail: evaid@ltkalmar.se

ALLVIN R., BERG K., IDVALL E. & NILSSON U. (2007)

Postoperative recovery: a

concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing

doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04156.x

Abstract

Title. Postoperative recovery: a concept analysis

Aim. This paper presents a concept analysis of the phenomenon of postoperative

recovery.

Background. Each year, millions of patients throughout the world undergo surgical

procedures. Although postoperative recovery is commonly used as an outcome of

surgery, it is difficult to identify a standard definition.

Method. Walker and Avant’s concept analysis approach was used. Literature retrieved from MEDLINE and CINAHL databases for English language papers

published from 1982 to 2005 was used for the analysis.

Findings. The theoretical definition developed points out that postoperative

recovery is an energy-requiring process of returning to normality and wholeness. It

is defined by comparative standards, achieved by regaining control over physical,

psychological, social and habitual functions, and results in a return to preoperative

level of independence/dependency in activities of daily living and optimum level of

psychological well-being.

Conclusion. The concept of postoperative recovery lacks clarity, both in its

meaning in relation to postoperative recovery to healthcare professionals in their

care for surgical patients, and in the understanding of what researchers in this area

really intend to investigate. The theoretical definition we have developed may be

useful but needs to be further explored.

Keywords: concept analysis, definition, nursing, postoperative, recovery

Introduction

A wide range of procedures are available to treat patients who

require surgical intervention. An important part of the patient

experience, irrespective of the type of procedure, is postoperative recovery. Research in this field is extensive and includes

studies of postoperative recovery as an outcome measure, e.g.

factors associated with length of hospitalization (Kehlet &

Dahl 2003), specific surgical procedures (Bay-Nielsen et al.

2004), and the use of specific pain management techniques

(Pavlin et al. 2005, Werawatganon & Charuluxanun 2005).

The emphasis in qualitative studies is on patient experiences in

postoperative recovery, and primarily factors associated with

specific diseases, e.g. gastrointestinal cancer (Olsson et al.

2002), gastro-oesophageal reflux (Nilsson et al. 2002) and

prostate cancer (Burt et al. 2005). Although postoperative

recovery is commonly used as a concept, it is difficult to identify

a standard definition. A conventional concept runs the risk of

being used without reflection. Furthermore, different disciplines may attribute different meanings to the same concept.

Concept analysis is a means to clarify over-used or vague

concepts that are prevalent in clinical practice, hence enabling

2007 The Authors. Journal compilation 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

1

R. Allvin et al.

those using the term to perceive it in the same way. The

purpose of concept analysis in nursing research is to examine

the basic elements of a concept by revealing its internal

structure and critical attributes (Walker & Avant 2005).

Knowledge changes over time. Hence, the understanding of a

concept should be considered as a dynamic, ongoing process

that is responsive to new knowledge and experiences (Meleis

2005).

Early discharge from hospital requires patients to handle

much of the postoperative recovery process on their own.

Defining recovery from a holistic perspective is essential for

nursing and for the advancement of postoperative care.

Formulating a definition of postoperative recovery promotes

understanding of its use in postoperative care and the factors

that influence it. Therefore, the aim of this study was to present

a concept analysis of the phenomenon postoperative recovery.

Methods

The scientific literature was searched to produce a definition

that explains the concept of postoperative recovery. We

searched the MEDLINE and CINAHL databases for English

language papers published from 1982 to October 2005 that

contained the following search terms: concept analysis,

recovery, anaesthesia, anesthesia, postsurgical, postoperative,

recovery process, post discharge, convalescence, rehabilitation used separately and in combination with each other.

The reference lists of all retrieved articles were searched for

additional studies. The papers included in the analysis

described and highlighted the phenomenon postoperative

recovery, i.e. the meaning of recovery. Papers were excluded

for example, where intervention and descriptive studies used

postoperative recovery as an outcome measure for pain,

nausea, mobilization, etc. Dictionaries and textbooks were

also searched for a definition of the concept. Walker and

Avant’s (2005) approach to concept analysis was used as the

method to define the concept postoperative recovery and a

total of 26 publications, one textbook and two dictionaries

were used in the analysis.

Findings

Dictionary and thesaurus definitions

Initial information about recovery was found in dictionaries

and a thesaurus. The Encarta World English Dictionary,

North American Edition (2005) defines recovery as:

The return to normal health of somebody who has been ill or

injured, the return of something to a normal or improved state after

2

a setback or loss, the regaining of something lost or taken away, the

extraction of useful substances from waste or refuse (environment),

the obtaining of something by the ruling of a court (law), a return

to the guard position after making an attack (fencing), and the

bringing forward of the arm to make another stroke (rowing

swimming).

According to the Wordsmyth English Dictionary – Thesaurus

(2005), synonyms for recovery are: recoup, salvage, return,

convalescence and cure.

Uses of the concept

In ambulatory surgery, postoperative recovery can be divided

into three phases: early, intermediate and late recovery

(Steward & Volgyesi 1978, Korttila 1995). The early phase

lasts from discontinuation of anaesthesia until patients have

recovered their vital protective reflexes. The intermediate

phase lasts from when patients have regained stable vital

functions until readiness for discharge home. The late phase

lasts from discharge until the patients reach preoperative

health and well-being (Steward & Volgyesi 1978, Marshall

& Chung 1999). Presumably, the three phases of recovery

would also apply to hospital inpatients.

From a holistic perspective, postoperative recovery is

described as a process defined by improvement in functional

status and the perception that one is recovering (Zalon 2004).

Another description is a return to wholeness that occurs by

conservation of energy and reinstatement of integrity (Levine

1991). Pain, depression and fatigue are related to patients’

self-perceptions of postoperative recovery after abdominal

surgery and after coronary artery by-pass graft surgery

(Zalon 2004). Patients have also major concerns about

returning to independence in activities in daily life (Kirkevold

et al. 1996, Moore 1997). Physical sensations associated with

fatigue, pain from chest and leg incisions, pain in shoulder

and neck muscles, and pain while coughing are part of the

recovery process (Moore 1997). Pain and fatigue are the most

common and severe symptoms in postoperative recovery

(Moore 1997, Hodgson & Given 2004, Zalon 2004, Nilsson

et al. 2006) and indicate impaired structural integrity after

surgery (Zalon 2004). According to Levine (1991), fatigue is

a sign of limited energy resources, which is described as both

physical and psychological energy loss (Nilsson et al. 2006).

Postoperative fatigue may be caused by reduced energy and

preoperative anxiety (Nilsson et al. 2006). Pain, depression

and fatigue are also significantly related to functional status

and self-perception of recovery in older postoperative

abdominal patients (Zalon 2004). Psychological sensations,

e.g. negative emotions including depression, anger and

2007 The Authors. Journal compilation 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

JAN: THEORETICAL PAPER

anxiety are also part of the recovery process (Moore 1997).

Depression reduces the conservation of personal integrity and

has been associated with lower functional status after surgery

(Zalon 2004).

Signs of recovery include a continuous decrease in discomforting bodily symptoms (Olsson et al. 2002). Physical

symptoms that overwhelm patients in the first months after

surgery are described as a kind of prison (Olsson et al. 2002)

and patients’ experiences from surgery can be an extensive

personal shock (Theobald & McMurray 2004).

As a psychosocial phenomenon, recovery has been studied

as abandoning the sick role (Parsons 1975). In a study by Kasl

and Cobb (1966), recovery was associated with discharge, as

an outcome measure for factors associated with the length of

hospitalization. This study examined the sick role at a

behavioural level, in which recovery was defined as leaving

the sick role to resume normal social obligations. A decade

later, a study of abandoning the sick role after cardiac bypass

surgery extended the research beyond hospitalization, and

recovery was described as returning to work (Brown &

Rawlinson 1977). The psychosocial recovery process also

involves interacting with other people and is more complex

and time-consuming than recovery of self-oriented activities.

Patients seem to focus on regaining physical, cognitive and

practical functions before focusing on relating to others

(Kirkevold et al. 1996). When an individual becomes

disabled, it is expected that treatment will be sought. When

this happens, the individual becomes dependent on others for

care. After a shorter or longer period, caregivers help the

patient develop the skills needed to take responsibility for

self-care (Andreoli 1990, Nilsson et al. 2006). To optimize

the recovery process, some patients require more detailed

discharge information on what to expect after surgery

(Theobald & McMurray 2004).

The availability of social support is important for

psychological well-being during the recovery process (Baker

1990, Nilsson et al. 2006). Psychological well-being is

influenced by met or unmet expectations, positive or

negative physical symptoms and positive or negative feelings

of personal competence (Baker 1990). This has also been

shown to be a significant factor influencing functional

recovery when controlling for age, comorbidities, site of

disease and symptoms (Hodgson & Given 2004). Recovery

can be described as regaining one’s optimum level of wellbeing (Andreoli 1990).

Baker (1989) conceptualized recovery as a phenomenon

that extended beyond discharge. Postdischarge recovery was

described as a process of returning to normal, as defined by

pre-illness comparative standards of physical, social and

psychological well-being. This process moves successively

Postoperative recovery

through three phases: passivity, activity resumption and

stabilization. Passivity is a time of rest to support physical

convalescence. During activity resumption, people prepare

for their return to a full range of activities. Stabilization starts

when they have returned to a full range of pre-illness, social

role functions. Reasons for resuming, or not resuming,

activity are dependent on cues and pressure. Those who

experienced congruence of cues and pressures reported

positive feelings about the recovery process. People who

perceived negative physical symptoms, especially fatigue, and

who were unable to respond to pressures, expressed frustration (Baker 1989).

The recovery process includes turning points, or recovery

indicators, defined as recovery trajectories. ‘Critical junctures’ in the trajectory can be identified as either improvements or setbacks in relation to the expected outcome. The

recovery trajectory is based on the belief that the patient will

recover. There is a wide recovery trajectory, but also multiple

smaller trajectories, e.g. concerning mobility and personal

hygiene. Each particular trajectory corresponds with the

progression and control of bodily functions as patients move

towards recovery, and these shifts in control are defined as

‘recovery markers’. Recovery could be described as becoming

independent and regaining control over one’s bodily functions and body care (Lawler 1991).

Defining attributes

Concept analysis requires the determination of the defining

attributes of characteristics that are most frequently associated with the concept and appear repeatedly in references to

it, according to Walker and Avant (2005). Based on their

approach, the defining attributes of recovery after surgery

are: (a) an energy-requiring process, (b) a return to a state of

normality and wholeness defined by comparative standards,

(c) regaining control over physical, psychological, social and

habitual functions, (d) returning to preoperative levels of

independency/dependency in activities of daily living and

(e) regaining one’s optimum level of well-being.

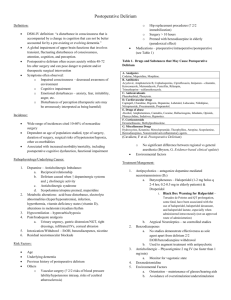

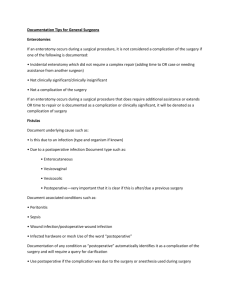

Several dimensions emerge from the literature. The

postoperative recovery process is divided into four dimensions, i.e. physiological, psychological, social and habitual

recovery (Table 1). In physiological recovery, patients

improve their functional status by regaining control over

reflexes and motor activities, normalized and controlled

bodily functions, loss of pain and fatigue and conservation

of energy. Passivity is also a part of physiological recovery.

Psychological recovery includes returning to psychological

well-being and wholeness, reinstated integrity, transition

from illness to health, loss of depression, anger, anxiety,

2007 The Authors. Journal compilation 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

3

R. Allvin et al.

Table 1 Dimensions of postoperative recovery found in the literature

nausea, but was completely exhausted and had little muscle strength.

She was happy to have her family, who supported her in practical

Physiological

Regain control over reflexes and motor activities

Normalize and control bodily functions

Loss of pain and fatigue

Conservation of energy

Experience of passivity

Psychological

Experience of passivity

Return to psychological well-being

Return to wholeness

Reinstate integrity

Transition from illness to health

Loss of depression, anger, anxiety, fatigue and passivity

Experience of pressures and cues

Social

Becoming independent

Stabilize at full social function

Functioning in interaction with other people

Habitual

Stabilizing the full range of activities

Take responsibility for and controlling activities in daily care

Restoration of normal eating, drinking and toilets habits

Returning to work and driving

activities, e.g. buying food, cleaning the house, and caring for the

dog. Successively, she managed to return to the activities she

performed prior to surgery. Four weeks after surgery she returned

to work. By that time her wound was healed, and she had no

remaining physical symptoms. She was satisfied with the outcome of

surgery, as the bleeding had ceased. She was also relieved to know

that she did not have cancer. Fatigue was the only remaining

problem, since she was still tired and had little strength. She was

unable to manage even minor tasks after coming home from work.

This fatigue continued for about three months, after which she

regained normal strength in relation to her preoperative standard and

expectations.

This case demonstrates the defining attributes. Lisa’s recovery

was a process over time. She achieved effective treatment for

her physical symptoms. She experienced fatigue, which

forced her to rest and conserve energy. Successively, she

regained control over her physical and habitual functions. She

managed to return to work and to various activities. Also,

Lisa was happy with the result of her operation and felt

relieved that she did not have cancer.

fatigue and passivity. Psychological recovery also includes

experiences of pressures and cues. In the dimension of social

postoperative recovery, the patient strives to become independent and to stabilize at full social function, which

includes interacting with other people. In the habitual part

of recovery, the patient works towards stabilizing the full

range of activities by taking responsibility for and controlling activities in daily care, normal eating and drinking

habits, returning to work and driving.

Borderline case

Borderline cases are examples that contain most, but not all,

of the defining attributes (Walker & Avant 2005), for

example:

A 67-year-old man was in the garden with his wife and friends when

he suddenly experienced intense stomach pain. His wife called for an

ambulance, and he was taken to hospital. He was operated on

immediately, and the surgeon found that he suffered a colon rupture

Model case

caused by a tumour. During the early postoperative phase he

According to Walker and Avant (2005), a model case

demonstrates all of the defining attributes of the concept. A

model case for postoperative recovery appears below:

experienced severe pain. He was also shocked by the fact that he

had been operated on, and that he had a cancerous tumour. After a

few days it became clear that he had a wound infection. He was very

tired and had to remain in hospital for about two weeks. During this

Lisa is a 47-year-old woman who had a hysterectomy to treat

time he successively progressed regarding mobilization and intake of

bleeding. There were no complications during anaesthesia and

fluid and food. After discharge, he feared that something else could

surgery, and the entire procedure went smoothly. Lisa woke up in

happen to the wound. He was exhausted and needed a great deal of

a postanaesthesia recovery unit and was transported to the surgical

rest. In the first weeks, before he had the courage to leave the house,

ward a few hours later. Thanks to effective pain treatment she did not

he exercised indoors. Because of the cancer he required chemother-

experience pain, but was bothered by mild postoperative nausea. She

apy, which caused him considerable problems with diarrhoea and

managed to drink and eat and made successive progress in mobil-

nausea. After six months he had regained control over his physical

ization, toileting, and personal hygiene. Before surgery she had been

and practical functions and was able to return to independence in

worried about her diagnosis. She feared that a cancer disease caused

activities of daily living. However, because of the chemotherapy he

her symptoms. Afterwards, she was able to relax when a biopsy

had not returned to optimum psychological well-being. He experi-

revealed no malignancy. Lisa was discharged from the hospital four

enced side effects from the treatment and was still bothered by the

days after her operation. At that time she did not experience pain or

fact that he had cancer. He did not know what to expect in the future.

4

2007 The Authors. Journal compilation 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

JAN: THEORETICAL PAPER

This man had reached the turning point for recovering

physical and habitual functions, but had not recovered

emotionally.

Related case

Related cases are similar to the concept and relate to it in

some way, but do not contain all the defining attributes

(Walker & Avant 2005). The following is an example:

A 39-year-old man was restoring his house. He was working alone

when he suddenly fell from a ladder. His wife found him lying

unconscious on the floor. An acute operation was necessary to stop

the bleeding in his brain. After surgery, he successively regained

control over physical functions. The process took several months. He

needed considerable rest, but managed to return to independence in

daily activities. The wound healed, and he does not have any residual

Postoperative recovery

surgery, caused by injury, illness or other factors. Surgery

leads to physical, psychological, habitual and social interruption.

Consequences are those events or conditions that occur as a

result of the concept (Walker & Avant 2005). Postoperative

recovery is an energy-demanding process with turning points

starting directly after surgery and extending beyond discharge. The intended consequence is to return to preoperative

physical, psychological, habitual and social status, an

optimum level of well-being, and preoperative levels of

independence/dependency in activities of daily living. Lawler

(1991) states that recovery means returning to independence

and regaining of control over bodily functions. We think that

a person needing assistance in activities of daily living can

also recover, not to a level of independence, but to their

former level of dependence.

conditions. However, this traumatic experience caused him to reflect.

It brought out other issues that had nothing to do with the surgery.

Empirical referents

This case is similar to the model case, but the process evolved

beyond the specific recovery from surgery. He searched for

meaning in his experience. The recovery process evolved into

more of a healing process.

According to Walker and Avant (2005), ‘Empirical referents

are classes or categories of actual phenomena that by their

existence or presence demonstrate the occurrence of the

concept itself’ (p. 73). In some cases, the empirical referents

are identical to the attributes (Walker & Avant 2005).

Several instruments are available that purport to measure

quality of recovery after anaesthesia and surgery (Myles et al.

1999, 2000a, Myles et al. 2000b, 2001, Leslie et al. 2003).

Also, several studies report on the development of instruments to evaluate the effectiveness of different interventions

during the recovery period (Aldrete & Kroulik 1970, Wolfer

& Davis 1970, Hogue et al. 2000, Kleinbeck 2000). Lee and

Steven (2000) reviewed the literature to discuss and describe

different approaches towards measuring recovery. They

stated that recovery is a process occurring over several

months, affected by factors such as adequate information;

anaesthetic and surgical techniques; restoration of normal

eating, drinking and toilet habits; loss of anxiety, depression

or fatigue; mobilization and rehabilitation to full social

functioning; and changing from a state of illness to a state of

health (Lee & Steven 2000).

Contrary case

Contrary cases are examples of what the concept is not

(Walker & Avant 2005). For example:

A 70-year-old woman was treated by knee replacement surgery. It

was an elective procedure, and she was well-prepared both

physically and mentally. The operation was performed using a

combined spinal-epidural block. When the ward nurse was doing

her routine postoperative monitoring on the first evening after

surgery she discovered that the patient had a total muscle

blockade. This appeared to be the result of bleeding in the

epidural space. Surgery was performed, but too late to avoid tissue

damage. The woman needed to spend the rest of her life in a

wheelchair.

This case demonstrates the opposite of recovery. A healthy

woman underwent elective surgery, which resulted in serious

tissue damage. She did not return to a preoperative level of

wholeness, but developed a new condition. Her situation was

much worse after the operation than before.

Antecedents and consequences

Antecedents are those events or incidents that must occur

prior to the occurrence of the concept (Walker & Avant

2005). With recovery in this context, the antecedent is

Discussion

A limitation in our study was the number of papers found,

and presumably the papers not found, through our search

strategy using search terms for postoperative recovery.

Valuable information might have gone undetected. Another

problem concerns synonyms. Convalescence is one of the

synonyms for recovery, according to the Wordsmith English

Dictionary. In a study (Jakobsen et al. 2003) aimed at

2007 The Authors. Journal compilation 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

5

R. Allvin et al.

What is already known about this topic

• The term postoperative recovery is commonly used, but

it is not a clearly defined concept.

• Postoperative recovery is often associated with discharge from care, as an outcome measure for factors

associated with the length of hospitalization.

• Several instruments have been developed to measure

different aspects of postoperative recovery.

What this paper adds

• A definition of the concept postoperative recovery.

• Postoperative recovery is an energy-requiring process

that has four dimensions – physiological, psychological,

social and habitual recovery.

• Postoperative recovery is complex and includes different

turning points in the return to normality and wholeness.

describing convalescence after laparoscopic sterilization, the

data collected included time until return to work and

performance of core activities of daily living. These parameters could also be included in the definition of recovery

according to our concept analysis. Jakobsen et al. (2003) did

not define or describe the concept of convalescence, but used

different parameters as outcome measures for convalescence.

Similar papers using the concept of convalescence, or other

synonyms, were not included in our analysis. This also

highlights the complexity of a concept analysis and the

importance of describing the meaning of the different

concepts used in research.

We used Walker and Avant’s (2005) approach to define the

concept of postoperative recovery. This approach was useful

because of the systematic method. We also think that, for the

nurses in clinical practice, the cases clarify the complexity of

the concept. However, it is important for all healthcare

professionals to understand this complexity. Postoperative

recovery is a process starting directly after surgery and

existing beyond discharge and including different turning

points; it does not only involve cessation of physical

symptoms. Our definition of postoperative recovery has a

holistic perspective, which helps the nurses and other

healthcare professionals to support, treat, inform and understand surgical patients on their way back to preoperative

levels of independence/dependency.

Although the scientific literature commonly refers to the

concept of postoperative recovery, a theoretical definition of

the concept is difficult to find. Hence, in this concept analysis,

we aimed to formulate a definition of recovery in this specific

context, i.e. after surgery. The attributes have been identified,

6

four dimensions of recovery have been described, and the

definition of postoperative recovery produced from this

concept analysis is as follows:

Postoperative recovery is an energy-requiring process of returning to

normality and wholeness as defined by comparative standards,

achieved by regaining control over physical, psychological, social,

and habitual functions, which results in returning to preoperative

levels of independence/dependence in activities of daily living and an

optimum level of psychological well-being.

According to Walker and Avant (2005, p. 64), a concept

analysis should never be viewed as a finished product and ‘the

best one can hope for is to capture the critical elements of it at

the current moment in time’. We believe that the current

critical elements of postoperative recovery have been captured in our definition. Our concept analysis could be a first

approach in a theory-building process for postoperative

recovery. A practice-oriented theory could, for example, be

useful for nurses in clinical practice aimed at guiding actions

in this complex area. Our ongoing research projects concerned with postoperative recovery will give more knowledge

and should be useful in a future theory synthesis (Walker &

Avant 2005).

Conclusion

The concept of postoperative recovery lacks clarity, both in

terms of what postoperative recovery means to healthcare

professionals in their care for surgical patients, and in

understanding what researchers really intend to investigate.

The theoretical definition we have developed may be useful

but needs to be further explored.

Author contributions

RA, KB, EI and UN were responsible for the study conception

and design and the drafting of the manuscript. RA and UN

performed the data collection and data analysis. EI and UN

provided administrative support. RA, KB, EI and UN made

critical revisions to the paper. EI and UN supervised the study.

References

Aldrete J.A. & Kroulik D. (1970) Postanesthesia recovery score.

Anesthesia and Analgesia 49(6), 924–933.

Andreoli K.G. (1990) Key aspects of recovery. In Key Aspects of

Recovery (Funk S., Tornquist E. & Champagne M., eds), Springer

Publish, New York, pp. 308–314.

Baker C.A. (1989) Recovery: a phenomenon extending beyond discharge. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice 3(3), 181–194.

2007 The Authors. Journal compilation 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

JAN: THEORETICAL PAPER

Baker C.A. (1990) Postoperative patients’ psychological well-being:

implications for discharge preparation. In Key Aspects of Recovery

(Funk S., Tornquist E. & Champagne M., eds), Springer Publish,

New York, pp. 308–314.

Bay-Nielsen M., Thomsen H., Andersen F.H., Bendix J.H., Sorensen

O.K., Skovgaard N. & Kehlet H. (2004) Convalescence after inguinal herniorrhaphy. British Journal of Surgery 91(3), 362–367.

Brown J.S. & Rawlinson M.E. (1977) Sex differences in sick-role

rejection and in work performance following cardiac surgery.

Journal of Health and Social Behaviour 18, 276–292.

Burt J., Caelli K., Moore K. & Anderson M. (2005) Radical prostatectomy: men’s experiences and postoperative needs. Journal of

Clinical Nursing 14(7), 883–890.

Encarta World English Dictionary, North American Edition.

Retrieved from http://www.encarta.msn.com/encnet/features/

dictionary/0550126 on 25 January 2005.

Hodgson N.A. & Given C.W. (2004) Determinants of functional

recovery in older adults surgically treated for cancer. Cancer

Nursing 27(1), 10–16.

Hogue S.L., Reese P.R., Colopy M., Fleisher L.A., Tuman K.J.,

Twersky R.S., Warner D.S. & Jamerson B. (2000) Assessing a tool

to measure patient functional ability after outpatient surgery.

Anesthesia Analgesia 91, 97–106.

Jakobsen D.H., Callesen T., Schouenberg L., Nielsen D. & Kehlet H.

(2003) Convalescence after laparoscopic sterilization. Journal of

Ambulatory Surgery 10, 95–99.

Kasl S.V. & Cobb S. (1966) Health behaviour, illness behaviour, and

sick-role behaviour. Archives of Environmental Health 12, 532–

541.

Kehlet H. & Dahl J.B. (2003) Anaesthesia, surgery, and challenges in

postoperative recovery. The Lancet 362(6), 1921–1928.

Kirkevold M., Gortner S.R., Berg K. & Saltvold S. (1996) Patterns of

recovery among Norwegian heart surgery patients. Journal of

Advanced Nursing 24, 943–951.

Kleinbeck S.V.M. (2000) Self-reported at-home postoperative

recovery. Research in Nursing and Health 23, 461–472.

Korttila K. (1995) Recovery from outpatient anaesthesia. Factors

affecting outcome. Anaesthesia 50(Suppl), 22–28.

Lawler J. (1991) The body in recovery, dying and death. In Behind

the Screens. Nursing, Somology, and the Problem of the Body

(Lawler J., ed.), Churchill Livingstone, Singapore, pp. 177–193.

Lee J. & Steven R. (2000) Recovery from surgery: grappling with an

elusive concept. Hospital Medicine 61(3), 189–192.

Leslie K., Troedel S., Irwin K., Pearce F., Ugoni A., Gillies R.,

Pemberton E. & Dharmage S. (2003) Quality of recovery from

anaesthesia in neurosurgical patients. Anaesthesiology 99, 1158–

1165.

Levine M.E. (1991) The conservation principles: a model for health. In

Levine’s Conservation Model: A Framework for Practice (Schaefer

K.M. & Pond J.B., eds), FA Davis, Philadelphia, pp. 1–11.

Marshall S.I. & Chung F. (1999) Discharge criteria and complications after ambulatory surgery. Anesthesia and Analgesia 88(3),

508–517.

Meleis A I. (2005) Theoretical Nursing: Development and Progress,

3rd ed. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia.

Postoperative recovery

Moore S.M. (1997) Effects of interventions to promote recovery in

coronary artery bypass surgical patients. Journal of Cardiovascular

Nursing 12(1), 59–70.

Myles P.S., Hunt J.O., Nightingale C.E., Fletcher H., Beh T., Tanil

D., Nagy A., Rubinstein A. & Ponsford J.L. (1999) Development

and psychometric testing of a quality recovery score after general

anesthesia and surgery in adults. Anesthesia Analgesia 88, 83–90.

Myles P.S., Reeves M.D.S., Anderson H. & Weeks A.M. (2000a)

Measurement of quality of recovery in 5672 patients after anaesthesia and surgery. Anaesthesia Intensive Care 28, 276–280.

Myles P.S., Weitkamp B., Jones K., Melick J. & Hensen S. (2000b)

Validity and reliability of a quality of recovery score: the QoR-40.

British Journal of Anaesthesia 84(1), 11–15.

Myles P.S., Hunt J.O., Fletcher H., Solly R., Woodward D. & Kelly

S. (2001) Relation between quality of recovery in hospital and

quality of life at 3 months after cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology 95,

862–867.

Nilsson G., Larsson S. & Johnsson F. (2002) Randomized clinical

trial of laparoscopic versus open fundoplication: evaluation of

psychological well-being and changes in everyday life from a

patient perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology

37(4), 385–391.

Nilsson U., Unosson M. & Kihlgren M. (2006) Experience of postoperative recovery before discharge – patient’s views. Journal of

Advanced Perioperative Care 2, 97–106.

Olsson U., Bergbom I. & Bosaeus I. (2002) Patients’ experiences of

the recovery period 3 months after gastrointestinal cancer surgery.

European Journal of Cancer Care 11, 51–60.

Parsons T. (1975) The sick role and the role of the physician

reconsidered. Milbank Memorial Fund quarterly. Health and

society 53, 257–278.

Pavlin D.J., Pavlin E.G., Horvath K.D., Amundsen L.B., Flum D.R.

& Roesen K. (2005) Perioperative rofecoxib plus local anesthetic

field block diminishes pain and recovery time after outpatient

inguinal hernia repair. Anesthesia and Analgesia 101(1), 83–89.

Steward D J. & Volgyesi G. (1978) Stabilometry: a new tool for the

measurement of recovery following general anaesthesia for outpatients. Canadian Anaesthetists’ Society Journal 25, 4–6.

Theobald K. & McMurray A. (2004) Coronary artery bypass graft

surgery: discharge planning for successful recovery. Journal of

Advanced Nursing 47(5), 483–491.

Walker L.O. & Avant K.C. (2005) Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing, 4rd ed. Pearson Prentice Hall, New Jersey.

Werawatganon T. & Charuluxanun S. (2005) Patient controlled

intravenous opioid analgesia versus continuous epidural analgesia

for pain after intra-abdominal surgery. Cochrane Database of

Systematic Reviews CD004088, doi: 10.1002/14651858.

CD004088.pub2.

Wolfer J.A. & Davis C.E. (1970) Assessment of surgical patients’

preoperative emotional condition and postoperative welfare.

Nursing Research 19(5), 402–414.

Wordsmyth English Dictionary. Retrieved from http://www.

wordsmyth.net/live/home/050126 on 25 January 2005.

Zalon M.L. (2004) Correlates of recovery among older adults after

major abdominal surgery. Nursing Research 53(2), 99–106.

2007 The Authors. Journal compilation 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

7