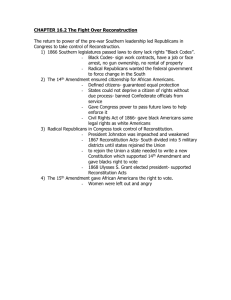

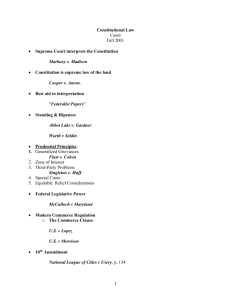

Equal Protection by Law: Federal

advertisement