Mission statements: in search for ameliorated performance through

advertisement

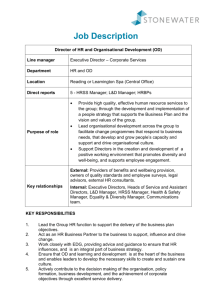

Mission statements: in search for ameliorated performance through organisation – employee value congruence. Drs. Sebastian Desmidt Prof. Dr. Aimé Heene Department of Management and Organisation Faculty of Economics and Business Administration Ghent University B-9000 Ghent Tel. 0032 (0)9.264.34.94 Fax 0032 (0)9.264.78.88 sebastian.desmidt@UGent.be Paper presented at the First workshop of the EGPA Study Group on Ethics and Integrity of Governance Mission statements: in search for ameliorated performance through organisation – employee value congruence. Abstract: Over the past 20 years mission statements have become one of the most popular management tools. Despite their enormous popularity mission statements are often, in practice as well as in academic literature, approached with resistance, scepticism, and even cynicism. Attitudes that are often nurtured by the vagueness that surrounds “guiding instruments” like mission statements and the tendency by some to impute mission statements with almost mythical powers able to resolve every organisational problem. Nevertheless once beyond the vagueness and thick mist the academic literature seems convinced that mission statements can produce a host of positive benefits and contribute to uplift organisational performance (Bart, 1998, Duncan, 1994, Dunn, 1994, Ireland, 1992, Mintzberg, 1987, Pearce II, 1987, Stone, 1996). Hereby implying a positive relation between the implementation of a mission statement and organisational performance. According to the psychological school mission statements provide a cultural glue of norms and values which influence the behaviour of organisational members (Campbell, 1991, Campbell, 1997, Coleman, 1997, Collins, 1995, Klemm, 1991, Lencioni, 2002, Leuthesser, 1997, Logan, 1984). These shared values, according to the psychological school, account for the positive relation between the implementation of a mission statement and organisational performance. Based on these findings this paper wants to suggest a conceptual framework supported by academic literature to examine the relationship between mission statement values and organisational performance by introducing the construct “commitment” as an intermediate variable. Key words Mission statement, commitment, values, sense of mission, organisational performance 2 During the last decades various changes have influenced the appearance of the public sector. Evolving expectations of society and altering visions on public sector performance have encumbered the public sector in general. In order to cope with changes in the remote and operational environment of public organisations many scholars and practitioners proposed to incorporate “proven” private sector management tools in public sector organisations (Hood, 1991). A frequently applied (private sector) concept to overcome an environment more and more characterized by dynamism, complexity, diversity and even hostility is strategic management. Strategic management fundamentally aims to set direction, to focus effort, to define the organisation and to provide consistency (Mintzberg, 1987). According to many authors (Baetz, 1996, Bart, 1996, Pearce II, 1982) the process of strategic management starts with crafting a mission statement. The popularity of mission statements stems primarily from the assumed positive relation between the formal phrasing of a mission statement and organisational performance. But what is a mission statement? Contrary to the collective enthusiasm with which practitioners have embraced (a recent world-wide study by Bain & Co revealed that mission statements are the most popular management tool used by companies) mission statements, the academic literature has not agreed on a general accepted terminology yet (Haberberg, ). Terms such as mission statement, business mission, statement of purpose and value statement are often used to underpin overlapping and interchangeable concepts (Schwartz, 2001). Even if a consensus arouse about a hierarchy of terminologies, various authors often fill in the mentioned concepts differently. Some authors even speak of a “terminological jungle”. This Babel-like confusion roots in the fact that up till know research has focused mainly on inductively analysing mission statements in order to develop checklists of mission statement items or even a general mission template. As almost each researcher tried to develop a new typology of mission statement components, rather than building on previous findings, a considerable diversity appears to exist regarding the ideal mission statement definition (Bart, 1997). In spite of the prevailing theoretical confusion it is possible to distinguish two schools of thought: “broadly speaking, one approach describes mission in terms of business strategy, while the other expresses mission in terms of philosophy and ethics (Campbell, 1991)”. Ted Levitt and Peter Drucker can be considered as the founding fathers of the strategic school of mission. In his article “Marketing Myopia” Levitt (Levitt, 1960) proclaims that many organisations have the wrong business definition. Managers should define more carefully 3 their business in order to focus on customer need rather than on production technology. Accordingly Drucker (Drucker, 1974) stressed in the 1970s that business purpose and business mission are rarely given adequate thought. Organisations often neglect to answer the basic question: “What business are we in?” (David, 1989). Based on this “hard” approach of the concept “mission statement” several authors defined a mission statement as a formal document answering “some fairly basic, yet vitally important, questions: what is our purpose? Why do we exist? What are we trying to accomplish? (Bart, 1997)”. In contrast, the psychological or cultural school of mission statement stresses the “soft” components that a mission statement should address. “A mission is the cultural glue which enables an organisation to function as a collective unity. This cultural glue consists of strong norms and values that influence the way in which people behave, how they work together and how they pursue the goals of the organisation (Campbell, 1991)”. The underpinning element in this approach is the importance of core values in an organisation. “Core values […] are the organisation’s basic precepts about what is important in both business and life, how business should be conducted, its view of humanity, its role in society, the way the world works, and what is to be held inviolate (Collins, 1991)”. In order to overcome the shortcomings of both schools, several authors proposed to integrate the strategic and cultural schools of thought. Pearce and David for example stated that an effective mission statement “defines the fundamental, unique purpose that sets a business apart from other firms of its type and identifies the scope of the business’s operations in product and market terms. It is an enduring statement of purpose that reveals an organisation’s product or service, markets, customers and philosophy (Pearce II, 1987)”. Although the “hard” components prevail, the soft component “philosophy” holds a prominent place. One of the most respected attempts to integrate both views on an equal basis and by some even considered as a more or less universally accepted (Chun, 2001, Hooley, 1992) set of mission components is the Ashridge-model (Campbell, 1993, Campbell, 1992, Campbell, 1991). According to the Ashridge-model a mission statement should consist of 4 reinforcing basic elements: purpose, values, strategy and behaviour standards: 4 “Why the Company Exists” PURPOSE “The Competitive Position and Distinctive STRATEGY VALUES “What the Company Believes in” BEHAVIOUR STANDARDS “The Policies and Behaviour Patterns that Underpin the Distinctive Competence and Value Now that we have gained more insight into the components a mission statement should preferably encompass, raises the simple question raises: “Why?” Why do so many practitioners as well as scholars devote precious resources to developing and/or studying mission statements? The answer is as simple as the question itself: it is almost generally recognized that mission statements make a difference (Baetz, 1996, Bart, 1998, Campbell, 1991, Pearce II, 1987, Weiss, 1999). Most scholars depart thus from the assumption that a well-crafted mission statement will positively influence organisational performance “and that mission statements are equally important for firms in a variety of strategic contents: large versus small, profit versus non-profit, simple versus complex (Morris, 1996)”. Although empirical evidence supporting the presumed positive relationship between mission statement and organisational performance is scarce and results are very mixed, the most commonly assumed benefits from mission statements are: (1) enhanced resource allocation, (2) strengthened legitimisation and (3) reinforced shared expectations / values. Enhanced resource allocation and strengthened legitimisation congruous with the strategic view on mission statements. By clarifying the unique purpose of the organisation, its principal stakeholders and how to satisfy their needs, the organisation constructs a strategic framework that serves as a guideline for decision-making. By specifying the philosophy that will guide the company it is hoped that stakeholders will accept, trust and support the organisation (de Wit, ) with the required resources (Heene, 2001). Promoting shared expectations / values refers to the cultural glue that can tie individuals together, creating a common identity. 5 As mentioned above empirical evidence underpinning the assumed benefits of a well-defined mission statement is rather scarce and fragmented (Baetz, 1996, David, 1989, Klemm, 1991, Wilson, 1992). The limited attempts made at linking a performance indicator (mostly of a financial nature) with an organisation’s mission statement found no significant difference in performance (Baetz, 1996, David, 1989, Klemm, 1991, Wilson, 1992). However when performance is measured in terms of impact on desired employee behaviour Bart and Baetz found in different research settings consistently strong positive relationships indicating that various mission statement components (e.g. presence of values) have the ability to influence employee behaviour (Baetz, 1996, Bart, 1996, Bart, 1996). The scarce quantitative research thus seems to support the assumptions of the psychological school (Coulson-Thomas, 1992): by providing employees a clear image of desired behaviour and esteemed values, the concept of shared values and beliefs can influence in a powerful way the behaviour of employees (Calfee, 1993, Truskie, ). Based on these findings this wants to suggest a conceptual framework to examine the relationship between the value-component of mission statements and organisational performance as supposed by the psychological school. Although this presumed relationship seems to be supported by empirical data, it is still very roughly defined and unexplored. Based mainly on work by Bart, Campbell, Collins and Pearce this paper aims to unravel the different elements causing an organisation to establish a fit between the desired conduct of organisational members and their actual conduct by defining a mission statement. The proposed conceptual model starts with emphasizing the need for a “valid mission”. A valid mission statement is attained when the formal mission statement expresses values (defined by Rokeach as “abstract ideals, positive or negative, not tied to any specific object or situation, representing a person’s beliefs about modes of conduct and ideal terminal modes … which transcendentally guide actions and judgements across specific objects and situations (Rokeach, 1968)”) that are truly a part of the organisational culture. There must be an actual congruency between the formal expressed values of the organisation and the underlying implicit values of the organisation. 6 Mission Values Value Congruence Valid Mission Organisational Values A formal mission statement must be firmly grounded in the day-to-day reality of organisational life (Campbell, 1997). The purpose of a mission statement is not to enumerate an extensive list of values with the sole purpose of adorning the annual report or organisational website. Mission statements must mirror those values that are embedded in the organisational culture. Statements that are merely window dressing will evoke cynical reactions and lose all credibility (Bartkus, 2000). Once the implicit organisational values are made explicit an effort must be made to disperse them throughout the organisation. Once all employees are aware of the core values of the organisation a second delicate process, which forms the cornerstone of the proposed conceptual model, emerges. According to Campbell (Campbell, 1997) the values and behaviour standards contained in mission statements can evoke three kind of response: (1) The yawn of boredom. The mission statement is a bland motherhood and apple pie – statement impossible to appeal. (2) Emotional resistance. The expressed organisational values differ from the values held high by the individual employee. Value-conflicts arise and will have a negative influence on the organisation – employee relation. (3) Emotional support. “The reader recognizes the values and feels uplifted by being associated with them. It brings an emotional applause.” It is self-explanatory that only the third response evokes a positive influence. Consequently a match between the value system of the individual and the value system of the organisation is a key element as values are important determinants of employee behaviour in organisational settings. Personal Values Value Congruence Explicit Organisational Values 7 Based on the Image Theory, an alternative descriptive theory of decision-making, Liedtka (Liedtka, 1989) argues that the concept of value congruence becomes in issue only in its absence. Given such a lack of congruence, logically, the strongest value system will dominate. As the hallmark of a strong value system is set by the extent to which the underlying values are consonant (at individual as well as organisational level), Liedtka distinguishes two potential sources of conflict around values: “(1) internal conflict, within the self, and (2) external conflict, between the self and the outside environment (the organisation) for our purposes”. Hereby suggesting that the interplay between individual and organisational value systems can be summarized in a matrix consisting of two similar bipolar scaled dimensions: Organisational Values Individual Values Consonant Contending Contending I II Consonant III IV In quadrant I of the Value Congruence Model a strong organisational culture dominates the employee – organisation relationship. Compliance with organisational values is expected. In quadrant II the organisational values are not clear. For an employee with a contending value system, it will be very encumbering to notice that the organisation itself is struggling with a value conflict and sends out mixed messages. “With no unified corporate value system existing to serve as referent, individuals would be particularly susceptible to group influence”. In quadrant III the outcome can be dual (symbolised by the diagonal line), depending on the degree of fit between organisational and individual values, given that the individual as well as the organisation have of a consonant value system: value congruence or value conflict. In quadrant 4 strongly held individual values dominate in an environment of contending individual values. “The behaviour fostered by this muddled organisational message might be reflected in the opportunism of those who indulge, with little apparent sense of wrong-doing, in insider trading, abetted in their pursuits by organisations whose espoused codes of conduct differ from those actually in use (Liedtka, 1989).” Several authors (Collins, 1995, Want, 1986) refer to the concept of value congruence, a crucial element in the relationship “mission statement – performance”, as a “sense of mission”. Campbell and Yeung (Campbell, 1991) define a “sense of mission” as “an 8 emotional commitment felt by people towards the company’s mission”. They believe that a sense of mission occurs “when there is a match between the values of an organisation and those of an individual”, as they noticed that in above average performing companies “the commitment and enthusiasm among employees seem to come from a sense of personal attachment to the principles on which the company operates”. “Companies that assert more boldly what they stand for typically attract and retain employees who identify with their values and become more deeply committed to the organisation that embodies them (Bartlet, 1994)”. Cornerstone of the concept “sense of mission” is the expected influence of value congruence on employee commitment (Balazas, 1990, O'Reilly, 1991, Pozner, 1985, Valentine, 2002), which in turn has been found to be associated with desirable outcomes and valued behaviours (Boxx, 1991, Newton, 1999) and contributes to improved organisation effectiveness (Dick, 2001, Scholl, 1981) and the overall organisational performance (Connor, 1975, Elizur, 1996, Kidron, 1978, Putti, 1989, Wiener, 1980): Value Congruence Organisational Commitment Organisational Performance According to Elizur and Koslowsky (Elizur, 2001) “commitment refers to the attachment, emotionally and functionally, to one’s place of work”. This psychological attachment to the employing organisation can take several forms (Newton, 1999): (1) Calculative or compliance commitment (Allan, 1990, Hrebiniak, 1972) and (2) attitudinal or affective commitment (Mowday, 1998, O'Reilly, 1986). Calculative commitment is based on rewards received and the threat of losing them while attitudinal commitment is based on feeling a feeling of belonging to the organisation or on shared values and goals with the employer. Hall, Schneider and Nygren (Hall, 1970) use the term “moral commitment” to describe commitment that requires “the individual’s incorporation of organisational values and goals into his own identity”. It is obvious that the term “commitment” used in the concept “sense of mission” refers to attitudinal commitment. The level of attitudinal commitment of an individual towards his employing organisation is of high importance as both the organisation and the individual benefit when commitment is high 9 (Randall, 1987). As Valentine et al. (Valentine, 2002) listed strong organisational employee commitment leads to decreasing absenteeism (Hammer, 1981) and employee turnover (Abelson, 1983) as well as increasing satisfaction (Hunt, 1985), performance (Morris, 1981) and organisational adaptability (Abelson, 1983). Furthermore the reciprocal character of the relationship between “value congruence” and “attitudinal commitment” augments its impact on organisational performance since committed employees will tend to reinforce the existing organisational value structure (Herndon, 2001). Increased commitment “should therefore increase employees’ feeling of connectedness to an [organisation], as well as their support for [organisational] values (Valentine, 2002)”. As stated above value congruence between the organisation and the employee will ameliorate, through the intervening variable of commitment, organisational performance. Based on the above-mentioned rationales and academic literature this study would like to suggest a theoretical framework articulating the relationships that lead from formulating mission statements to subsequent organisational performance through the mediating variable of commitment: Sense of Mission Personal Values Value Congruence Organisational Commitment Organisational Performance Explicit Organisational Values Valid Mission Value Congruence Organisational Values Mission - Organisational Alignment Mission Values 10 Comments and discussion: It is self-evident that the postulated relations in the proposed model are neither deterministic nor fully determined by one single factor. The complexities of inter and intra-organisational relationships makes it nearly impossible to conceive a model that embraces all possible influencing components. The proposed model therefore rests on certain preconditions. In order for the suggested cascade of relations to occur and for mission statements to influence the behaviour of corporate agents some implicit prerequisites must be fulfilled: (1) Well-Conceived: the formal mission statement has to reflect the actual values of the organisation. By mirroring the values of employees mission statements will create, inspire and energize workforce. “One’s faith and trust in the organisation’s integrity depends on observed conformity between what the organisation says it stands for and what it is perceived to do (Fritz, 1999).” Unfortunately in reality “most […] statements are bland, toothless, or just plain dishonest. And far from being harmless, as some executives assume, they’re often highly destructive. Empty […] statements create cynical and dispirited employees, alienate customers, and undermine managerial credibility” (Lencioni, 2002). (2) Well-Communicated: all members of the organisation have to be aware of the existence of the mission statement. Organisation must make a real effort to communicate the mission statement effectively and thus heighten the employee penetration level, according to Schwartz “the extent to which employees are aware as opposed to unaware of their code (Schwartz, 2001)”, of mission statements. (3) Well-Comprehended: all organisation members have to understand the mission statement. Employees must clearly grasp the values and principles that will guide them in their day to day and future activities (Stone, 1996) (4) Well-Supported: the mission statement have to be embedded in the systems, procedures and policies of the organisation. Or as Bart et al. (Bart, 2001) define it: missionorganisational alignment. Mission statements can only have an impact on an organisation when they are “integrated into every employee-related process-hiring methods, performance management systems, criteria for promotions and rewards, and even dismissal policies (Lencioni, 2002). 11 Once these conditions are fulfilled mission statements have the ability to influence behaviour through intervening variables. The proposed model puts “attitudinal commitment” in the forefront as an intervening variable. Although it is widely agreed that attitudinal commitment is a dependent variable of value congruence and internalisation of organisational values (Balazas, 1990, O'Reilly, 1991, Pozner, 1985), a simple bivariate relationship of value congruence and commitment is in all probability too much of a simplification of the complex reality. Dick and Metcalfe (Dick, 2001) summarized the key antecedents of commitment by using two broad headings: (1) individual factors and (2) managerial factors. Individual factors influencing organisational commitment are: hierarchical position (Benkhoff, 1997, McCaul, 1995), position tenure (Gregersen, 1992, Motaz, 1988), organisational tenure (Mathieu, 1989, Mathieu, 1990) and age (Mathieu, 1990). Managerial factors influencing organisational commitment are: level of organisational and managerial support, involvement in decision-making (Beck, 2000, Beck, 1997, Mowday, 1998, Porter, 1974), amount of feedback received about job performance and job role (Mathieu, 1990), and leadership style (Blau, 1985, Williams, 1986). Furthermore it is obvious that the intermediate variable “commitment” is not the sole variable to determine the relationship between value-congruence and organisational performance. Motaz (Motaz, 1997) for example puts “employee satisfaction” in the forefront as antecedent of commitment while others stress “motivation” to fill in the “black box” between valuecongruence and behaviour. It is clear that the proposed conceptual framework in this study needs to be confronted with empirical data in order to corroborate and refine the assumed relations. Empirical testing will help to address untouched questions such as: (1) Which values relate most strongly with employee commitment? (2) To what degree does employee commitment influence organisational performance? (3) Is the relation between value-congruence and employee commitment positively or negatively influenced by other variables? (4) Is the relation between employee commitment and organisational performance positively or negatively influenced by other intermediate variables? (5) Is the relation between value congruence and organisational performance positively or negatively influenced by other intermediate variables? 12 Bibliography: Abelson, M.A. 1983. The Impact of Goal Change on Permanent Perceptions and Behaviors of Employees'. Journal of Management, 9: 65-79. Allan, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. 1990. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance, and normative commitments to the organisation. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(1): 1-18. Baetz, Mark C.; Bart, Christopher K. 1996. Developing mission statements which work. Long Range Planning, 29(4): 526-33. Balazas, A.L. 1990. Value Congruency: The Case of the "Socially Responsible" Firm. Journal of Business Research., 20(2): 171-81. Bart, Christopher K. 1996. High tech firms: Does mission matter? Journal of High Technology Management Research, 7(2): 209-25. Bart, Christopher K. 1996. The impact of mission on firm innovativeness. International Journal of Technology Management, 11(3/4): 479-93. Bart, Christopher K. 1997. Industrial firms and the power of mission. Industrial Marketing Management, 26(4): 371-83. Bart, Christopher K. 1998. Mission matters. CA Magazine, 131(2): 31-33. Bart, Christopher K., Baetz, M.C. 1998. The relationship between Mission Statements and Firm Performance: An Exploratory Study. The Journal of Management Studies, 36(26): 82353. Bart, Christopher, K., Bontis, Nick, Taggar, Simon. 2001. A model of the impact of mission statements on firm performance. Management Decision, 39(1): 19-35. Bartkus, Barbara; Glassman, Myron; McAfee, Bruce. 2000. Mission Statements: Are They Smoke and Mirrors? Business Horizons, Nov / Dec: 23 - 28. Bartlet, C.A., Ghoshal, S. 1994. Changing the Role of Top Management: Beyond Strategy to Purpose. Harvard Business Review, 72(6): 79-88. Beck, K.; Wilson, C. 2000. Development of affective commitment: a cross-sectional sequential change with tenure. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 56(1): 114-36. Beck, K.; Wilson, C. 1997. Police officers' views on cultivating organisational commitment: implications for police managers. Policing: an International Journal of Police Strategies and Management, 20(1): 175-95. 13 Benkhoff, B. 1997. Ignoring commitment is costly: new approaches to establish the missing link between commitment and performance. Human Relations, 50(6): 701-26. Blau, G. 1985. The measurement and prediction of career commitment. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 58(4): 277-88. Boxx, W. Randy, Odom, Randall Y. 1991. Organizational values and value congruency and their impact on satisfaction, commitment, and. Public Personnel Management, 20(2): 195205. Calfee, David L. 1993. Get Your Mission Statement Working! Management Review, 82(1): 56-59. Campbell, A. 1993. The Power of Mission: Aligning Strategy and Culture. Planning Review (Special Issue). Campbell, A., Nash, L.L. 1992. A sense of mission. Reading, M.A.: Addison - Wesley Publishing Co. Campbell, A., Yeung, S. 1991. Creating a Sence of Mission. Long Range Planning, 24(4): 1020. Campbell, Andrew. 1997. Mission statements. Long Range Planning, 30(6): 931-32. Chun, Rosa. 2001. E--reputation: The role of mission and vision statements in positioning strategy. Journal of Brand Management, 8(4/5): 315-34. Coleman, John F. (Skip). 1997. Using mission statements in the fire service: Do you know... Fire Engineering, 150(8): 60-64. Collins, J.C., Porras, J.L. 1991. Organizational Vision and Visionary Organizations. California Management Review, 34(1): 30-52. Collins, James C.; Porras, Jerry I. 1995. Building a visionary company. California Management Review, 37(2): 80-100. Connor, Patrick E., Becker, Boris W. 1975. Values and the Organization: Suggestions for Research. Academy of Management Journal, 18(3): 550-61. Coulson-Thomas, Colin. 1992. Strategic Vision or Strategic Con?: Rhetoric or Reality? Long Range Planning, 25(1): 81-88. David, F.R. 1989. How Companies Define Their Mission. Long Range Planning, 22(1): 9097. de Wit, Bob; Meyer, Ron. 1998. Strategy. Process, Content, Context. 2de ed: Tomson Learning. 14 Dick, G.; Metcalfe, B. 2001. Managerial factors and organisational commitment. A comparative study of police officers and civilian staff. The International Journal of Public Sector Management, 14(2): 111-28. Drucker, P. 1974. Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, and Practices. New York: Harper & Row. Duncan, W. Jack; Ginter, Peter M. 1994. A sense of direction in public organizations. Administration & Society, 26(1): 11-27. Dunn, M.G. 1994. The impact of organizational values, goals, and climate on marketing effecitiveness. Journal of Business Research, 30(2): 131-41. Elizur, Dov. 1996. Work Values and Commitment. International Journal of Manpower, 17(3): 25-30. Elizur, Dov, Koslowsky, Meni. 2001. Values and organizational commitment. International Journal of Manpower, 22(7/8): 593-99. Fritz, Janie M. Harden, Arnett, Ronald C. 1999. Organizational ethical standards and organizational commitment. Journal of Business Ethics, 20(4): 289-97. Gregersen, H.B.; Black, J.S. 1992. Antecedents to commitment to a parant company and a foreign operation. Academy of Management Journal, 35(1): 65-90. Haberberg, Adrian; Rieple, Alison. 2001. The Strategic Management of Organisations: Prentice Hall. Hall, D.T.; Schneider, B.; Nygren, H.T. 1970. Personal Factors in Organizational Identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 15(2): 176-90. Hammer, T.; Landau, J.; Stern, R. 1981. Absenteeism When Workers have a Voice: The Case of Employee Ownership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 66(5): 561-73. Heene, Aimé. 2001. Praktijkboek Strategie. Tielt: Lannoo / Scriptum. Herndon, N.C.; Fraedrich, J.P.; Yeh, Q. 2001. An investigation of Moral Values and the Ethical Content of the Corporate Culture: Taiwanese Versus U.S. Sales People. Journal of Business Ethics, 30(1): 73-85. Hooley, G.J., Cox, A.J. and Adams, A. 1992. Our five year mission - to boldly go where no man has gone before. Journal of Marketing Management, 8(1): 35-48. Hrebiniak, L.G.; Alutto, J.A. 1972. Personal and role-related factors in the development of organizational commitment. Administrative Science Quarterly, 18(4): 555-73. 15 Hunt, S.D.; Chonko, L.B.; Wood, V.R. 1985. Organisational Commitment and Marketing. Journal of Marketing, 49(1): 112-26. Ireland, R.D., Hitt, M.A. 1992. Mission Statements: Importance, Challenge and recommendations for Development. Business Horizons, 35(3): 34-42. Kidron, Aryeh. 1978. Work Values and Organizational Commitment. Academy of Management Journal, 21(2): 239-48. Klemm, M., Sanderson, S., Luffman, G. 1991. Mission Statements: Selling Corporate Values to Employees. Long Range Planning, 24(3): 73-78. Lencioni, Patrick M. 2002. Make Your Values Mean Something. Harvard Business Review, 80(7): 113-17. Leuthesser, L., Kohli, C. 1997. Corporate Identity: The Role of Mission Statements. Business Horizons, 40(3): 59-66. Levitt, T. 1960. Marketing Myopia. Harvard Business Review, 38(4): 45-56. Liedtka, J.M. 1989. Value Congruence: The Interplay of Individual and Organisational Value Systems. Journal of Business Ethics, 8(10): 805-15. Logan, George M. 1984. Loyalty and a Sense of Purpose. California Management Review, 27(1): 149-56. Mathieu, J.; Hamel, D. 1989. A cause model of the antecedents of organisational commitment among professionals and non-professionals. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 34: 229-317. Mathieu, J.; Zajac, D. 1990. A review of meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates and consequences of organisational commitment. Psychological Bulletin, 108(2): 171-94. McCaul, H.S; Hinsz, V.B.; McCaul, K.D. 1995. Assessing organisational commitment: an employee's global attitude towards the organisation. Journal of Applied Behavioural Science, 31(1): 89-90. Mintzberg, Henry. 1987. The Strategy Concept II: Another Look at Why Organizations Need Strategies. California Management Review, 30(1): 25-33. Morris, J.; Sherman, J.D. 1981. Generalizability of Organisational Commitment Model. Academy of Management Journal, 24(3): 512-26. Morris, Rebecca J. 1996. Developing a mission for a diversified company. Long Range Planning, 29(1): 103-15. Motaz, C. 1988. Determinants of organisational commitments. Human Relations, 41(6): 46782. 16 Motaz, C.J. 1997. A analysis of the relationship between work satisfaction and organizational commiment. Sociological Quarterly, 28(4): 947-76. Mowday, R.T. 1998. Reflections on the study and relevance of organisation commitment. Human Resource Management Journal, 8(4): 387-401. Newton, Mcclurg, L. 1999. Organisational Commitment in the Temporary-help Service Industry. Journal of Applied Management Studies, 8(1): 5-26. O'Reilly, C.A.; Chatman, J.; Caldwell, D. 1991. People and Organisational Culture: A Q-sort Approach to Assessing Person - Organisational Fit. Academy of Management Journal, 34(3): 487-516. O'Reilly, C; Chatman, J. 1986. Organizational commitment and psychological attachement: the effects of compliance, identification, and internalization on prosocial behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3): 492-99. Pearce II, J.A, David, F. 1987. Corporate Mission Statements: The Bottom Line. Academy of Management Executive, 1(2): 109-14. Pearce II, J.A. 1982. The Company Mission as a Strategic Tool. Sloan Management Review, 2(3): 15-24. Porter, L.W.; Steers, R.M.; Mowday, R.T.; Boulian, P.V. 1974. Organisational commitment, job satisfaction and turnover among psychiatric technicians. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59(5): 603-09. Pozner, B. Z.; Kouzes, J. M. 1985. Shared Values Make a Difference: An Empirical Test of Corporate Culture. Human Resource Management, 24(3): 293-310. Putti, J.M.; Aryee, S. and Ling, T.K. 1989. Work Values and organisational commitment: a study in the Asian context. Human relations, 42(3): 275-88. Randall, D.M. 1987. Commitment and the Organisation: The Organisation Man Revisited. Academy of Management Review, 12(3): 460-71. Rokeach, M. 1968. Beliefs, Attitudes and Values. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Scholl, R.W. 1981. Differentiating Organizational Commitment From Expectancy as a Motivating Force. Academy of Management Review, 6(4): 589-99. Schwartz, M. 2001. The Nature of the Relationship between Corporate Codes of Ethics and Behaviour. Journal of Business Ethics, 32(3): 247-62. Stone, R.A. 1996. Mission Statements Revisited. SAM Advanced Management Journal, 61(1): 31-37. 17 Truskie, S. The Driving Force of Successful Organizations. Business Horizons, 27(4): 43-48. Valentine, S.; Godkin, L.; Lucero, M. 2002. Ethical Context, Organizational Commitment, and Person-Organization Fit. Journal of Business Ethics, 41(4): 349-60. Want, J.H. 1986. Corporate Mission: The Intangible Contributor to Performance. Management Review, 75(8): 46-50. Weiss, Janet A.; Piderit, Sandy Kristin. 1999. The Value of Mission Statements in Public Agencies. Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory, 9(2): 193-223. Wiener, Y and Vardi, Y. 1980. Relationship between job, organization, and career commiment and work outcomes: an integrative approach. Organisational Behavior and Human Performance, 26: 81-96. Williams, L.J.; Hazer, J.T. 1986. Antecedents and consequences of satisfaction and commitment in turnover models: a re-analysis using latent variable structural equation methods. Journal of Applied Psychology, 72(1): 219. Wilson, I. 1992. Realizing the Power of Strategic Vision. Long Range Planning, 25(5): 18-28. 18