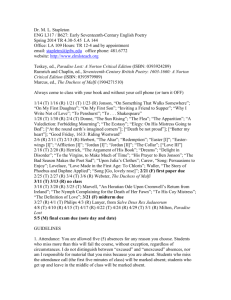

Recent Studies in the English Renaissance

advertisement