The Dividend Drill: Evaluating Long-Term Total Returns

advertisement

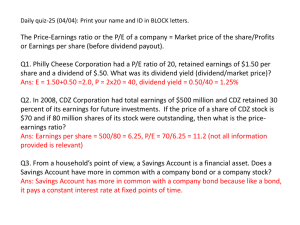

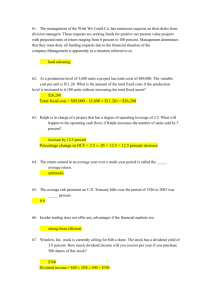

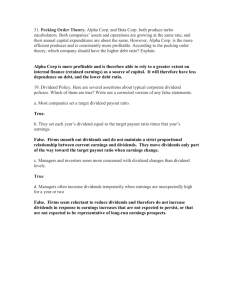

The Dividend Drill: Evaluating Long-Term Total Returns Why dividend yield plus growth equals total return. by Josh Peters, CFA, Equities Strategist, Editor, Morningstar DividendInvestor If you give a man a fish, he’ll eat for today, but if you teach a man to fish, he can eat for a lifetime. While we’re delighted to provide Morningstar’s best incomeoriented stock recommendations to you each month, we also want to teach what we know and learn about the art of fishing…for dividends, that is. What Is Total Return? Most people think about stocks the same way Will Rogers did: After folding dividends into our results, we earned a total return of 11.3% per year from National City (7.4% capital gain plus 3.9% in dividends), well above the 9.1% return from the S&P 500 (7.4% plus 1.6%). Our $1,656 investment, including reinvested dividends, grew into $4,843, or $876 more than the S&P 500. Of this total gain of $3,187, nearly half ($1,465) came through dividends. We see that dividends add directly—and often substantially—to the returns earned on long-term stock investments. But the relationship between dividends and total return runs much deeper than that. Consider that doubling of National City’s stock price—what would prompt investors to pay twice as much for a share of this bank at the end of 2005 than in 1995? What Drives Total Return? Don’t gamble; take all your savings and buy some good stock and hold it till it goes up, then sell it. If it don’t go up, don’t buy it. What Rogers describes—capital gains, the profit realized by the sale of a stock—is only one of several reasons to own stocks. If you’re trying to make money in the next 20 minutes, capital gains are the goal. But if you’re planning to own a stock for 2 years (or 20), the income return of the stock—dividends— becomes a larger piece of the puzzle. MDIDDMB0407 Let’s say we bought 100 shares of National City NCC, a Cleveland-based regional bank, at the end of 1995 for $16.56 per share. In the 10 years that followed, the share price roughly doubled to $33.57, an annual capital gain of 7.4%. On the surface, we’ve only matched the S&P 500, which also rose at a 7.4% annual pace. Nothing special, right? What we haven’t done yet is account for dividends. National City, like many banks, paid a handsome dividend averaging 3.9% of the share price over this period. This gave investors the opportunity to realize regular cash income from their investment without having to sell shares—or an opportunity to reinvest the dividends in additional, high-yielding shares. By contrast, the S&P 500 yielded just 1.6%. Supplement to Morningstar ® DividendInvestorTM In the long run, dividend growth will drive the stock price and, by extension, total returns. Having successfully expanded its operations from 1995 to 2005, National City’s board of directors raised the stock’s annual dividend rate from $0.72 per share to $1.48, for an increase of 106% (7.5% per year). This steady progress—reflected in the most concrete way possible, through the dividend—easily justifies the doubling of the stock price. In fact, long-term stock returns can be explained almost fully by this combination of yield and growth. In Triumph of the Optimists: 101 Years of Investment Returns, the authors wrote: The longer the investment horizon, the more important is dividend income. For the seriously longterm investor, the value of a portfolio corresponds closely to the present value of dividends. The present value of the (eventual) capital appreciation dwindles greatly in significance. In other words, total returns will trend toward dividend yield plus dividend growth—just as we saw with National City. The longer we own the stock, the greater the correlation. Even if we don’t plan on owning a stock for 101 years (or 10 years, or even 1 1 year), it’s this combination of income and income A cow for her milk, a hen for her eggs, And a stock, by heck, for her dividends. An orchard for fruit, bees for their honey, And stocks, besides, for their dividends. growth that forms a foundation for sound investment value. To see why this long-term relationship is true, we need to step back from the day-to-day (or even year-to-year) changes in the market price and look at the dividends a stock stands to pay far into the future. Williams never won any awards for his poetry. But his principle—that an investment security is worth the present value of future cash payments to its owner—defines to this day the intrinsic value of an investment. More on Dividend Theory Stocks are more than pretty pieces of paper. There needs to be tangible, underlying value to prompt an investor to own them. This means hard cash— most often transmitted via dividends. In his groundbreaking 1938 work, The Theory of Investment Value, John Burr Williams established that the same rules for evaluating cash flows applied to every type of investment. Earnings didn’t count, nor did book value; these were only proxies for dividend-paying ability. Only dividends—the cash returned to the investor— could make a stock worth owning. To make sure readers got the point, he composed a poem: Perpetuities in Practice Sum of Remaining 5-Year Bond Interest Received Principal Repaid Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 1,000.00 — — Total Cash Received: Present Value at 10% 100.00 90.91 100.00 82.64 100.00 75.13 100.00 68.30 1,100.00 683.01 — — 100.00 82.64 100.00 75.13 100.00 68.30 100.00 62.09 Infinite 620.92 Sum of Present Values Total Return % 1,000.00 10 Fixed-Rate Perpetuity Cash Received Present Value at 10% 100.00 90.91 Sum of Present Values Total Return % 1,000.00 10 Perpetuity with 5% Annual Growth Cash Received Present Value at 10% Sum of Present Values Total Return % 2 100.00 90.91 105.00 86.78 110.25 82.83 115.76 79.07 2,000.00 15 The Dividend Drill: Evaluating Long-Term Total Returns Year 5 121.55 75.47 Infinite 1,584.94 To see how this works, it helps to think about a stock in bondlike terms. With a bond, you have contractually certain payments of cash; unless the issuer goes bankrupt (not an issue with Treasuries), you know the day and amount of each interest payment and the eventual return of principal. If we have the current price of the bond, we can solve for the total return. Consider a bond in the accompanying example. It’s got a 10% interest rate that matures in 5 years. You know that for each $1,000 of par (principal) value, you’ll receive $100 in annual interest. If we demand a 10% return on our investment, we discount each year’s interest payment by that rate. Thus the first coupon we clip is worth not $100 in today’s dollars, but $90.91. The second payment is worth $82.64, and the third $75.13. By the time we’ve gotten our principal back in year five, the sum of these discounted values is $1,000. Assuming we can purchase this bond at par (100 cents for each dollar of principal value), our return on investment will be the 10% annual discount we require. We use a similar mathematical approach in evaluating the return from both stocks and bonds, though the securities themselves have critical differences. For one thing, the timing and amount of dividends is not contractually certain. A company may fall on hard times, omit the dividend, and go belly up. More important, stocks have perpetual lives—there’s no maturity date with a return of our principal at the end. Therefore it makes sense to evaluate a stock’s dividend stream as a perpetuity—a stream of cash with no end date. In the second example, you’ll find a $100 annual cash payment made in each year—just like the bond’s interest. Each year’s payments are discounted at 10%, just like the bond. With no maturity date, this discounting continues until the annual payments become little more than rounding errors (in year 50, for example, that $100 payment is worth just $0.85 in today’s dollars). But as each succeeding payment approaches zero in present-value terms, the sum total of all payments approaches $1,000. (Our reward for owning the perpetuity is in those time-value-of-money discounts.) With a little algebra, we can cut out all of those payments and simply define total return as income divided by price—in other words, yield. account for most, if not nearly all, the annual return for this stock. In fact, this is a real stock—General Electric GE, which at the end of 1955 sold for $57.75. Between 1955 and 2005, GE split its shares 7 times, so each original 1955 share is 96 shares today. And since then, GE has generated a compound annual total return of 11.6%. Fully 96% of this return is explained by initial dividend yield and subsequent dividend growth. And what of the stock price? Unadjusted for splits, GE rose from $57.75 to $3,364.80 per share, an annual growth rate of 8.5%. What could drive growth like that? The dividend—it rose at a nearly identical 8.3% clip. Total Return for Fixed Perpetuity 5 Yield Now, let’s introduce a growth rate to our income stream. We see that the present value of future dividend payments doesn’t shrink nearly as fast. The present value of our first $100 payment a year from now is still $90.91, but at a 5% growth rate the second payment will be $86.78 instead of $82.64, and the third $82.83 rather than $75.13. We’re starting to collect substantially more cash from this investment than from the zero-growth stream. Even this growing stream will eventually generate payments in present-value terms that approach zero, but in the meantime the sum of these future payments is approaching $2,000, not $1,000. Experimenting with discount rates, we find that we’d have to assess a 15% time value of money for the net present value to equal $1,000. But again, the algebra cuts all of this out—the return is equal to the 10% yield plus the 5% growth rate. Total Return for Growing Perpetuity 5 Yield 1 Growth Perpetuities in Practice Imagine a stock trading at $57.75 per share with a $1.60 dividend, for a yield of 2.8%. Over the next 50 years, that dividend grows at 8.3% annually. If the authors of Triumph of the Optimists are right, this combination of yield and growth—11.1%—should Supplement to Morningstar ® DividendInvestorTM Dividend yield and dividend growth drive long-term returns, just as the authors of Triumph of the Optimists claim. Introducing the Dividend Drill The DividendInvestor approach starts with this perpetuity view of stocks: What can we expect through a combination of today’s yield and dividend growth far into the future? Stocks don’t have a contractual obligation to pay dividends, much less increase them. But we can still estimate the future cash payments of a stock by establishing the safety of the current dividend and then evaluating long-term growth potential. We can and often will start with a stock’s historical dividend growth rate. But past dividend growth alone isn’t going to tell us much about how fast the core business can really grow, or how much that growth will cost. Growth is not a given, nor is it free. With current yield as a given, our Dividend Drill is designed to provide insights into the drivers of dividend growth. These fall into a pair of distinct concepts: first, growth of the core business, which enlarges the pool of dollars available for dividends. Then we add the effect of share buybacks, which boosts the available dividend dollars for each remaining share. 3 Separated into these three components, our total return breaks down as follows: Return 5 Yield 1 (Core Growth 1 Share Shrink) To demonstrate how this model works, we’ll run our formula on US Bancorp USB, a stock I recommended to DividendInvestor subscribers in November 2005. Step One: Calculate Dividend Yield Dividend yield is readily obtainable. We take the indicated dividend rate and divide it by our stock price. US Bancorp pays $0.40 per share per quarter, or $1.60 per year. The stock recently sold around $35, for a yield of 4.6%. Step Two: Estimate Core Growth Core business growth involves no calculation per se, but does require some knowledge about the company, its prospects, the industry, the competitive landscape, and even the entire economy. I use several tools to think about how fast the business can grow. These include: 3 Historical growth rate 3 Sustainable growth rate 3 Mark to GDP Looking at long-term growth rates for sales, assets, and income can point us in the right direction. For US Bancorp, which has made a lot of acquisitions in the past decade, these statistics are likely to be misleading. We want growth only of the core business; we’ll deal with acquisitions separately. But with a minimally acquisitive bank like TCF Financial TCB, the long-term records might prove useful. TCF’s total assets and deposits have risen at respective 6% and 5% annual rates over the past decade, which—assuming this isn’t contradicted by our other tools—ought to be a reasonable figure for TCF. By the way, while we might look at long-term earnings growth, we shouldn’t use earnings per share, which could double-count the effect of share buybacks. 4 The Dividend Drill: Evaluating Long-Term Total Returns The sustainable growth rate (SGR) can also point us in the right direction. SGR represents how fast the company can grow without raising additional equity capital, and is calculated as: SGR 5 Return on Equity 3 (1 2 Payout Ratio) To understand how this works, think about the business as a savings account. If a savings account pays 10% interest (don’t we wish!) and we never make withdrawals, our balance will grow by 10% annually. If we withdraw half of each year’s interest income, our balance—and with it, our annual income stream—will grow only half as fast. Yet just because the SGR suggests theoretical growth of 10% doesn’t mean the firm will grow that fast in the real world. US Bancorp is earning returns on equity in the low 20s while paying out 55%-60% of profits as dividends, so its SGR is a bit over 10%. But growing that fast would mean adding $22 billion in assets every year. Expansion is likely to be slower than that. The third tool—my personal favorite—is to set our growth expectations relative to overall economic growth. I call this mark to GDP. Real U.S. GDP has grown at a fairly consistent 3.5% over any long period. And since corporations report results in nominal rather than real terms, I add 2.5% for inflation, giving us a benchmark for business activity of 6%. Of course, different industries and companies offer a variety of long-term growth rates. New technologies and emerging businesses will create more than their fair share of economic growth, so the average mature business will probably be closer to 4%-5% than 6%. And while some businesses may have zero or even negative growth prospects, it’s tough for almost any business to grow faster than the economy for very long periods. We might venture higher rates for wellestablished, wide-moat health-care and technology firms, but even for great companies like Johnson & Johnson JNJ or Microsoft MSFT, I wouldn’t bank on growth of more than 7%-8%. So how does US Bancorp stack up against this 6% benchmark? Deposits—the core of the banking business model—have grown at roughly the same rate as the economy over time. But because US Bancorp operates in slower-growing regions—mostly Midwest and Northwestern states—I knock a point off this growth rate and use 5%. (It never hurts to be cautious; we can always be pleasantly surprised later.) This is well within the bank’s sustainable growth rate, and, if we back out merger activity, 5% is reasonably consistent with the past. Step Three: The Cost of Growth Core growth adds directly to our total return prospects, but it doesn’t come free. The vast majority of businesses will have to invest in additional productive assets for earning power to rise. And earnings reinvested in the business don’t provide immediate benefit to shareholders. Our next step is to calculate how much the core growth rate will cost per share. We can derive this from the sustainable growth formula. According to Wall Street consensus estimates, US Bancorp is expected to earn $2.78 per share in 2007 and make a 24% return on equity. The sustainable growth rate tells us that if 100% of earnings are retained, the company could grow 24% per year. If we expect the bank to grow at 5%—less than one fourth of return on equity—it follows that this growth will require just 21% of earnings to be reinvested (5% divided by 24%). Our per share cost of growth is 21% of earnings per share, or $0.58. Not every firm will have a return on equity that represents required reinvestment. In some cases, free cash flow can give us a more accurate picture of reinvestment needs. Free cash flow is exactly what it sounds like—the net earnings of the business, less any net investment through capital spending, working capital, and such. You might think of free cash flow as having already “paid” for the core growth rate. Soft-drink giant Coca-Cola KO is a good example of this. Over the past 10 years, the company has converted 100% of net income to free cash flow. Its core growth hasn’t cost anything at all—the per share cost of growth (assuming we think Coke can maintain this performance) would be zero. In an extreme case, like Dividend Portfolio holding Compass Minerals CMP, free cash flow actually exceeds reported earnings by a fair amount, even though Compass is poised to expand the core business at about 5% annually. This step in our analysis highlights the impressive value of low-cost growth. Even many conservative investors won’t find midsingle-digit growth all that inspiring. But when we can obtain that kind of Dividend Drill Worksheet Step 1: Dividend Yield Step 2: Core Growth Step 3: Cost of Growth Step 4: Surplus Earnings Step 5: Share Shrink Dividend Rate $ Estimated using: Core Growth % Earnings Per Share $ Surplus Earnings $ % Dividend Rate $ Stock Price $ : Historical Rates = Mark to GDP : - Return on Equity Sustainable Growth Ratio X Earnings Per Share $ = Cost of Growth Per Share $ Dividend Yield Core Growth % + - Cost of Growth Per Share $ Stock Price $ Total Return Estimate : = = Totals from Dividend Yield, Core Growth and Share Shrink Surplus Earnings $ Share Shrink % + Supplement to Morningstar ® DividendInvestorTM % = % 5 growth by reinvesting only a small share of company earnings, we get to have our cake (nice growth) while getting to eat most of it (through dividends and buybacks). Step Four: Surplus Earnings Out of the company’s pool of earnings, we’ve now provided for the dividend as well as the cost of growth. Subtracting these two factors leaves us with what I call surplus earnings. For US Bancorp, subtracting the $1.60 dividend and another $0.58 for reinvestment from anticipated earnings per share of $2.78 leaves surplus earnings of $0.60 per share. This surplus generally has just three places to go: debt reduction (or cash accumulation), share buybacks, and acquisitions. If US Bancorp isn’t paying down debt, letting cash pile up, or making acquisitions, we’re left with buybacks. Step Five: Share Shrink Buyback math can boost our total returns significantly. With the stock at $35, US Bancorp’s surplus earnings are enough to annually retire 0.017 share for each share outstanding, boosting our future dividend growth rate an additional 1.7%. We fold this directly into our return estimate. Share shrink emphasizes the advantage of undervalued stocks. All else being equal, a low share price enables the company to buy back more shares for each surplus dollar of earnings. And that’s in addition to the higher dividend yield a lower price delivers. This is one of the back roads to superior returns that has made slow-growing but cash-rich businesses like Altria MO amazing investments over time. Rather than buying back its own stock, the bank may opt to buy back some other company’s shares. Growth by acquisition isn’t tantamount to core business growth—among other factors, the initial returns are typically much lower than the firm’s existing return on equity—but for mature companies, we can assume they’re paying roughly the same value for the acquisition that they could get from buying back their 6 The Dividend Drill: Evaluating Long-Term Total Returns own shares. (In the interest of simplicity, I’ll assume that most small, bolt-on acquisitions won’t destroy shareholder value.) Bottom Line Adding US Bancorp’s yield (4.6%), core growth rate (5%), and share shrink (1.7%) generates a prospective total return of 11.3%. That’s a nifty return by most standards, which is why we added the stock to our Dividend Portfolio once we found it trading at a margin of safety we deemed reasonable. And if anything this dividend growth forecast—6.7%—looks conservative compared to past growth in the double digits. I actually expect dividend growth of 8% or better in the next five years. Using the Dividend Drill For the steady, conservative stocks we seek in DividendInvestor, I’m finding the Drill works quite well. It’s simple and comprehensive, and helps us understand what we own and what to expect. Like any model, it has its drawbacks. It lacks the comprehensive application of the discounted cash-flow methodology Morningstar uses to derive fair value estimates. It’s not well suited to a firm whose profitability or growth is in flux. And we need some assurance that the dividend will rise as fast as our core growth and share shrink terms project. Some cash-rich businesses—like Wall Street Journal publisher Dow Jones DJ—fail to invest their surpluses wisely. If historical dividend increases are significantly smaller than projected growth, watch out. Most important, the Drill is for long-term investors only. In the short term, whatever returns the Drill suggests will get swamped by short-term price swings. But the longer our time horizon, the greater the likelihood that our returns will match this model. Look for us to refer to the Drill frequently in the issues ahead. œ The Math Behind the Drill Combining the sustainable growth rate with the Gordon growth model. by Josh Peters, CFA, Equities Strategist, Editor, Morningstar DividendInvestor The underlying methodology of the Dividend Drill is based on a well-known equity valuation model, the one-stage Gordon growth model: 68% in 2006 and a 43% payout ratio indicated for 2007, could conceivably expand at a rate of almost 40% annually. Were that true, we’d all be eating a lot more chocolate soon. If a firm’s SGR is in excess of the growth potential of existing operations, it follows that the firm need not retain as much profit as its current payout ratio implies. These retained profits are instead being channeled into other purposes: reduction of net debt, share buybacks, or acquisitions. Stock Price 5 Dividend / (Required Return2Dividend Growth Rate) and the sustainable growth rate, or SGR: Earnings Per Share Growth 5 Return on Equity 3 (1 2 Payout Ratio) For the Drill model, we use the stock’s current price, Consider Buying price, or fair value estimate as the stock price term and solve for required return, which becomes the prospective total return. The Gordon growth model is thus rearranged as: Total Return 5 (Dividend / Stock Price) 1 Dividend Growth Rate We then assume that dividend growth will match that of earnings over the long term, and substitute the SGR for the dividend growth term: Total Return 5 (Dividend / Stock Price) 4 [Return on Equity 3 Our model is predicated on a stable return on equity and, by extension, a stable capital structure—incremental capital commitments to be funded by existing proportions of debt and equity. That leaves us with two potential uses for excess earnings: buybacks and acquisitions. We further simplify the opportunity set by assuming that acquisitions—including the benefit of any merger synergies and future growth of the acquired operation—aren’t made at valuations too far from the company’s own share price. That leaves share buybacks as the model’s use for retained earnings not needed to support the expansion of core operations. The impact of share buybacks is to shrink the number of shares outstanding while earnings, all else being equal, hold constant. These buybacks are thus directly accretive to dividend growth per share. (1 2 Payout Ratio)] Further Development This stage of the model’s development is incomplete. Many, if not most, mature firms with high returns on equity have indicated SGRs far in excess of likely industry growth, usually capped at or near long-term nominal growth of U.S. GDP (about 6% annually). To the extent that certain industries, like health care, are gaining share as a proportion of economic activity, we may assume a growth rate slightly in excess of likely nominal GDP growth, as we do with J&J. In the final iteration of the model’s development, we replace the SGR with our estimate of actual earnings growth of core operations (core growth) and instead evaluate the impact of earnings that remain after funding the current dividend and core growth. One more step remains: How much does core growth cost? This is obtained by dividing this core growth forecast by return on equity, which yields the required retention ratio (the complement of payout ratio) and multiplying this term by earnings per share: Cost of Growth Per Share 5 (Core Growth / ROE) 3 EPS Yet the problem of excessive SGRs remains. For example, Hershey HSY, with a return on equity of Supplement to Morningstar ® DividendInvestorTM 7 Having established how much it costs to fund growth, and using the current dividend rate as a given, we can evaluate the earnings left after these two uses of cash. Dividing by the share price yields our final Dividend Drill term, which we call share shrink: evaluated over a 5- to 15-year horizon. Any intermediate-term deterioration in growth or return on equity would prompt us to reduce our core growth and return on equity estimates accordingly. Variations Share Shrink 5 (EPS 2 Dividend2 Cost of Growth Per Share)/Share Price Now we have the complete Dividend Drill model: Return 5 (Dividend / Share Price) 1 Core Growth 1 [ (EPS 2 Dividend 2 Cost of Growth Per Share) / Share Price ] Big Picture Theoretically, the Dividend Drill could be applied to any stock that pays a dividend. By assuming a hypothetical dividend paid out of retained earnings not needed for reinvestment, it could even be used to appraise the total return potential of nondividend-paying stocks. However, with only one stage, and that assuming a core growth rate and a return on equity in perpetuity, the model presents two theoretical challenges: First, growth may not continue at that rate indefinitely; second, incremental returns on equity should eventually be competed down to a normal rate of profit. Thus the Drill lacks the rigor of a complete discounted cash-flow analysis that ends in a terminal return on equity equal to the cost of equity capital. Further, because the share shrink term is contingent on the stock price at the time buybacks are made (rather than our price at the time of analysis), the eventual contribution to dividend growth from share buybacks will vary. We solve (or, perhaps more properly, evade) this challenge by e using the Drill only for relatively mature firms with stable (or improving) competitive characteristics and sustainable capital structures and r maintaining vigilance over the stocks evaluated with the Drill. Morningstar analysts keep watch over firms’ competitive positions and realistic long-term growth expectations. In practice, this tends to be 8 The Math Behind the Drill The message behind the Dividend Drill is to incorporate the three underlying drivers of returns: current income, income growth, and the cost of that growth. Yet not every firm’s financials or form of organization support a plain-vanilla, EPS-based use of the Drill. Compass Minerals, for example, needs to spend only 50%-60% of its annual depreciation. As a result, earnings understate free cash flow by a significant margin. In cases such as this, we may use a simplified version of the drill: Return 5 (Free Cash Flow / Stock Price) 1 Free Cash Flow Growth Rate Free cash flow is defined as cash from operations less capital expenditures. Since investments to support growth—capital spending plus net additions to working capital—are already accounted for, we’ve already “paid for” the company’s long-term growth rate. Further, free cash flow is assumed to be used for a combination of dividends and buybacks; because both of these terms are divided by the stock price to generate our dividend yield and share shrink terms, we can simply take free cash-flow yield to represent both terms. In some cases—such as master limited partnerships, which pay out nearly all of operating cash flow to unitholders—the current dividend and cost of growth per share combined exceed the earnings of the enterprise. In these cases, the share shrink term may well be negative—the firm faces continual equity issuance to fund growth. While this may appear dilutive to earnings, as long as the firm’s return on equity exceeds its cost of equity capital, such issuance will be accretive to dividend growth. œ