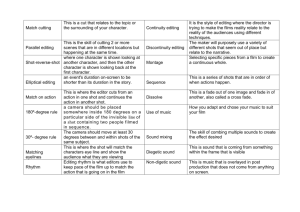

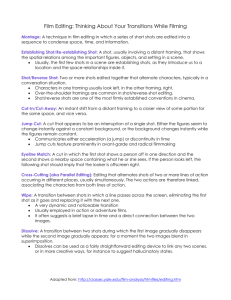

Reference Source for Media Literacy

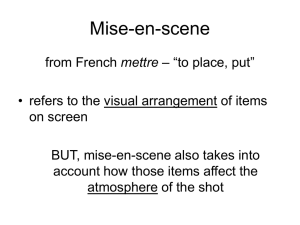

advertisement