File

advertisement

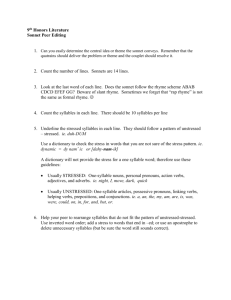

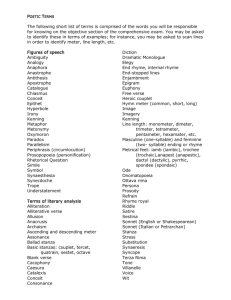

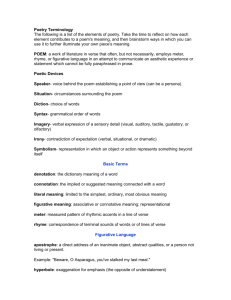

INTRODUCTION TO POETIC FORM: STRUCTURE, RHYME SCHEME, AND METER STRUCTURE: # of stanzas and # of lines per stanza Two lines: couplet Three lines: tercet Four lines: quatrain Five lines: cinquain Six lines: sestet Seven lines: septet Eight lines: octet/octave RHYME SCHEME: the pattern of rhyming words at the end of each line of a poem. The rhyming pattern is indicated by using letters (e.g.: ABAB CDCD). Feminine Rhyme: Lines rhymed by their final two syllables (e.g. “gunning” and “running”). Both the penultimate and the final syllables are stressed. E.g.: You broke my KNICK-KNACK/ Now I want a TIC-TAC Masculine Rhyme: Lines that rhyme with one stressed syllable. E.g.: Violets are BLUE/And I love YOU METER (a.k.a. verse): The measured pattern of rhythmic accents (stressed and unstressed syllables) in poems. Scansion: the analysis of verse into metrical patterns, identifying the type of metrical foot and the amount of feet per line Free Verse: Poetry without a regular pattern of meter or rhyme. Blank Verse: Non-rhyming iambic pentameter (meter without a rhyme scheme) Types of Metric “Feet”: Iambic foot: unstressed + stressed ex-CEPT (rising) Trochaic foot: stressed + unstressed FOOT-ball (falling) Anapestic foot: unstressed + unstressed + stressed com-pre-HEND (rising) Dactylic foot: stressed + unstressed + unstressed BLUE-berry (falling) Spondaic foot: stressed + stressed KNICK-KNACK Pyrrhic foot: unstressed + unstressed “When the” and “and the” are pyrrhic feet in the following sentence: “When the BLOOD PRICKS and the NERVES PRICK” Number of Metric Feet (per line): monometer dimeter trimeter tetrameter one foot two feet three feet four feet pentameter hexameter heptameter octameter five feet six feet seven feet eight feet Can you scan the poem/song excerpts and determine the meter through the magic of scansion? The morns are meeker than they were, The nuts are getting brown; The berry’s cheek is plumper, The rose is out of town. --Emily Dickinson Bats have webby wings that fold up; Bats from ceilings hang down rolled up; Bats when flying undismayed are; Bats are careful; bats use radar; --Frank Jacobs, “The Bat” You know that it would be untrue, You know that I would be a liar, If I was to say to you Girl, we couldn’t get much higher. Come on, baby, light my fire. Try to set the night on fire. --Jim Morrison, “Light My Fire” Consider the structure, rhyme scheme, and meter of the following sonnets: My Mistress’ Eyes are Nothing like the Sun—William Shakespeare My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun; Coral is far more red than her lips' red; If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun; If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head. I have seen roses damasked, red and white, But no such roses see I in her cheeks; And in some perfumes is there more delight Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks. I love to hear her speak, yet well I know That music hath a far more pleasing sound; I grant I never saw a goddess go; My mistress when she walks treads on the ground. And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare As any she belied with false compare. When I Consider How My Light is Spent-- Petrarch When I consider how my light is spent, Ere half my days in this dark world and wide, And that one talent which is death to hide Lodged with me useless, though my soul more bent To serve therewith my Maker, and present “My true account, lest He returning chide; "Doth God exact day-labor, light denied?" I fondly ask. But Patience, to prevent That murmur, soon replies, "God doth not need Either man's work or His own gifts. Who best Bear His mild yoke, they serve Him best. His state Is kingly: thousands at His bidding speed, And post o'er land and ocean without rest; They also serve who only stand and wait." Sestina by Elizabeth Bishop September rain falls on the house. In the failing light, the old grandmother sits in the kitchen with the child beside the Little Marvel Stove, reading the jokes from the almanac, laughing and talking to hide her tears. She thinks that her equinoctial tears and the rain that beats on the roof of the house were both foretold by the almanac, but only known to a grandmother. The iron kettle sings on the stove. She cuts some bread and says to the child, It's time for tea now; but the child is watching the teakettle's small hard tears dance like mad on the hot black stove, the way the rain must dance on the house. Tidying up, the old grandmother hangs up the clever almanac on its string. Birdlike, the almanac hovers half open above the child, hovers above the old grandmother and her teacup full of dark brown tears. She shivers and says she thinks the house feels chilly, and puts more wood in the stove. It was to be, says the Marvel Stove. I know what I know, says the almanac. With crayons the child draws a rigid house and a winding pathway. Then the child puts in a man with buttons like tears and shows it proudly to the grandmother. But secretly, while the grandmother busies herself about the stove, the little moons fall down like tears from between the pages of the almanac into the flower bed the child has carefully placed in the front of the house. Time to plant tears, says the almanac. The grandmother sings to the marvelous stove and the child draws another inscrutable house. Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night by Dylan Thomas Do not go gentle into that good night, Old age should burn and rave at close of day; Rage, rage against the dying of the light. Though wise men at their end know dark is right, Because their words had forked no lightning they Do not go gentle into that good night. Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay, Rage, rage against the dying of the light. Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight, And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way, Do not go gentle into that good night. Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay, Rage, rage against the dying of the light. And you, my father, there on that sad height, Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray. Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage against the dying of the light. Elegiac Poem Mission You and your group members will write a 12-line elegiac poem, mourning the death of any character of your choice from the literary canon (so long as the character dies in the text). Elegy Definition In general, an elegiac poem refers to any poem that serves as a eulogy. Elegy Meter and Form A classical elegiac poem, first composed by the Ancient Greeks, has a very particular structure. The poem is written in rhyming couplets of dactylic hexameter. This is the same meter as classical epic poetry; thus, its nickname is “heroic hexameter.” Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey as well as Virgil’s Aeneid are written in heroic hexameter. Dactylic “feet” are comprised of one stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables, producing the rhythmic effect of “DA-da-dum.” To get a feel for this kind of meter, read the lines from Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds, which is written in dactylic tetrameter (four “feet” per line): PICture your SELF in a BOAT on a RIVer with TANgerine TREE-ees and MARmalade SKI-iies. Since the classical elegiac poets would allow “spondees” (two stressed syllables) in the place of dactylic feet, the classical style is difficult to emulate. For example, a dactylic hexameter line could be comprised of five dactylic feet and a spondaic foot (two stressed syllables), as shown in the first line of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “Evangeline”: THIS is the FORest primEVal the MURmuring PINES and the HEM-LOCKS. To complicate things more, during the Romantic Era, poets like Thomas Gray, William Wordsworth, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge freed the elegy from its rhythm and rhyme scheme, reinventing the word “elegiac” to mean any poem written in the memory of the dead (without the heroic hexameter and rhyming couplets requirement). Here is an excerpt from Thomas Gray’s 1751 “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” written in iambic pentameter instead of heroic hexameter (and no couplets either): Here rests his head upon the lap of Earth A A youth to Fortune and to Fame unknown. B Fair Science frown'd not on his humble birth, A And Melancholy mark'd him for her own. B Special Guidelines for Your Elegy’s Meter and Form I would like your 12-line elegy to either stay true to the classical form by incorporating the heroic couplet rhyme scheme (AABBCCDDEEFF) or spice it up with the rebellious Romantics’ rhyme scheme variation (ABABCDCDEFEF). I would like you to play around with dactylic meter to engender the evocative “waltzlike” rhythm, but the amount of feet per line is up to you! Love Sonnet Mission Your group’s mission is to write a 14-line love sonnet to any character from the literary canon… in traditional Shakespearean sonnet form. Sonnet Meter and Form Sonnets are poems with 14 lines that are structured into three four-lines stanzas, also known as quatrains. Every sonnet ends in a couplet; the couplet usually summarizes the significance of the poem’s theme(s). Each line of a sonnet is written in iambic pentameter; thus, each line has five “feet.” An iambic “foot” is a combination of an unstressed syllable with a stressed syllable, producing the rhythmic effect of “da-DUM.” The rhythm of a line in iambic pentameter is… “da-Dum-da-DUM-da-DUM-da-DUM-da-DUM” The rhyme scheme of a sonnet is as follows: ABAB CDCD EFEF GG (Three quatrains and a couplet at the end) Here is a famous Shakespearean sonnet example: Let me not to the marriage of true minds A Admit impediments. Love is not love B Which alters when it alteration finds, A Or bends with the remover to remove: B O no! it is an ever-fixed mark C That looks on tempests and is never shaken; D It is the star to every wandering bark, C Whose worth's unknown, although his height be taken. D Love's not Time's fool, though rosy lips and cheeks E Within his bending sickle's compass come: F Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks, E But bears it out even to the edge of doom. F If this be error and upon me proved, G I never writ, nor no man ever loved. G Thematic Haiku Present a thematic message from a novel of literary merit through the terse lines of a traditional haiku. A haiku is a Japanese form of poetry, consisting of seventeen syllables partitioned in three metrical phrases of five, seven, and five. Deep within the stream The huge fish lie motionless Facing the current. --James W. Hackett In the amber dusk Each island dreams its own night The sea swarms with gold. --James Kirkup