Criminal Law reading notes

advertisement

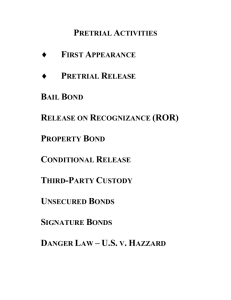

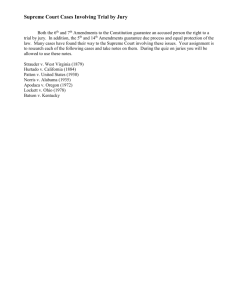

Joshua Dressler, Cases and Materials on Criminal Law 2nd. ed. (St. Paul, Minn: West Group, 1999) notes by chapter CHAPTER 1 A. Nature, sources, and limits of the criminal law 1. criminal law is a series of directions or commands, formulated in general terms, telling people what they can and cannot do. 2. they speak on the community's behalf, apply to that community, and are enforced by that community. 3. disobedience of these commands leads to sanctions these three things are the same as all other areas of law. What distinguishes criminal law, then? A criminal sanction is distinguished from a civil one by "the judgment of community condemnation which accompanies and justifies its imposition." [i.e., moral opprobrium; a crime "will incur a formal and solemn pronouncement of the moral condemnation of the community, typically followed by a punishment] Notes and questions: 1. Hart would disagree. He argues that a crime must be condemned as immoral by the community at large. (p. 3) A crime is an action that a majority of the community agrees is the manifestation of an individual's damaged moral sensibility. 2. A community-wide judgment of the immorality of the act is what separates the criminal from the civil process. [This would seem to indicate that should a society ever decide that murder was not immoral, then it would cease to be a crime in that society. Hart appears to be a cultural relativist.] 3. note on common law vs. statutory criminal law 4. It is fair to convict a person if they don't know the conditions listed in this note because an act deemed to be immoral by the community would be known as immoral by the person committing the crime, or should be if said person was moral. 5. constitutional provisions (ex post facto, cruel and unusual, must have due process) limit legislative lawmaking and must be considered when studying criminal law. 6. note on present-day role of judiciary 7. model penal code helped standardize and order state penal codes, which had previously been a hodgepodge of overlapping and even conflicting statutes. B. Criminal law in a procedural context: pre-trial Some statistics: (p. 7) – young people more likely victims of crime than older, most crimes are property crimes, majority of female victims knew their attacker, majority of male victims did not, women five times as likely to be victim of violence than man Even when a crime is reported, arrest not always made. Probable cause is necessary to make the arrest. The notion of probable cause is a fluid one. If probable cause met, suspect normally must be indicted by a grand jury (members of the community who determine if enough evidence exists to prosecute the accused). Next, accused is entitled to make pre-trial motions, which may get case dismissed. Accused may also enter a plea bargain. C. Criminal law in a procedural context: trial by jury Sixth Amendment: "in all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury." In all cased where the potential punishment exceed incarceration of six months, the jury, not the judge, must reach the requisite finding of "guilty." Sullivan v. Louisiana 508 US 275 (1993). In Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 US 145 (1968), Supreme Court argued that a right to jury protected against corrupt judicial officials and persecution by the Government. Jury is normally 12, but juries as small as 6 are permitted. Some state laws permit nonunanimous verdicts if a "substantial majority" has voted to convict. A juror is not impartial if "her state of mind in reference to the issues or parties involved in the case would substantially impair her performance as a juror in accordance with the court's instructions on the law. Adams v. Texas, 448 US 38 (1980). Such information is discovered in voir dire of prospective jurors (aka venirepersons). Peremtory challenges permitted on no basis, though the 14th Amendment Equal Protection Clause is violated if a venireperson is challenged solely on his race or gender. Batson v. Kentucky, 476 US 79 (1986) and other cases. Purpose of jury system: to defend against exercises of arbitrary power by the Government and to make available to defendants the common-sense judgment of the community, the accused is entitled to a jury drawn from a pool of persons constituting a fair cross-section of the community. Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 US 522 (1975). This right is violated if large distinctive groups of persons (women, racial or religious minorities) are systematically excluded from jury pools for illegitimate reasons. D. Proof of guilt at trial 1. Proof beyond a reasonable doubt Winship, 397 US 358 (1970): reasonable doubt standard reduces the risk of convictions resting on factual error; a society that values the good name and freedom of indiv should not condemn a man when reasonable doubt exists; moral force of criminal law must not be diluted when people are in doubt about a convict's guilt Notes and questions 1. better to let guilty go free than put innocent in jail? 2. what is "beyond a reasonable doubt"? US Supreme Court def as "subjective state of near certitude." Jackson v. Virginia, 443 US 307, (1979). 3. if reasonable doubt not quantifiable, how to instruct jurors? US Supreme Court held the Constitution neither prohibits nor requires trial courts to define the term. 4. which instruction do I find most helpful? I prefer the "firmly convinced" definition, as it is written in simple language and would allow me, as a juror, the easiest yardstick for measuring my judgment. AS a defense attorney, I think that strictest definition is the "Moral certainty" and would thus make it the most difficult to convict my client. 5. correct: no intution allowed in the "no hesitation" instruction 2. Enforcing the presumption of Innocence Owens v. State, court of appeals of Maryland, 1992. 93 Md.App. 162, 611 A.2nd 1043. Facts: Owens found behind wheel of car parked in a driveway with motor running and lights on. A state trooper found the man asleep with several open and empty containers of alcohol in his automobile. Owens was clearly intoxicated. Trial court, without jury, convicted him of drunken driving on this circumstantial evidence. Issue: Was there a reasonable hypothesis of innocence that prevents Owens from being convicted of drunken driving in a case based exclusively on circumstantial evidence? Holding: No, there was not. Conviction affirmed. Reasoning: A rule states: "A conviction upon circumstantial evidence alone is not to be sustained unless the circumstances are inconsistent with any reasonable hypothesis of innocence." Owens could not be convicted of drunken driving on a private highway. However, there are only two choices: either he drove to the driveway and parked, or was about to drive away. If he drove and parked, then he is guilty of drunken driving on a public road. Court must find a tiebreaker to decide which possibility is more likely. Appellant's residence address is unknown, therefore it cannot be used. It is, however, not likely that one would drink to excess in one's house, and then walk to one's car, with empty cans, turn on the lights and motor, and then pass out. Moreover, the state trooper approached the vehicle after being called there to investigate a suspicious vehicle. Not likely to receive such a call if appellant was at his home. The totality of these circumstances are inconsistent with a reasonable hypothesis of innocence. Notes and questions: 1. Yes, he is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt, unless he mounts a better defense, I cannot think of any reasonable situation where he was innocent. 2. court had to apply the "reasonable" test in order to comply with legal sufficiency requirement that circumstantial convicts also preclude any reasonable hypothesis of innocence. 3. Judge must insure the burden of proof stays with prosecution. Defendant can ask for a directed verdict of acquittal after prosecution's case and again after defense has rested and prosecution has had a chance to rebut. When does a judge decide to grant a motion for directed verdict? If judge decides jury must have doubt based on evidence, than he can dismiss case – jurors are not permitted to speculate or conjecture. 4. When an appeal court is faced with insufficiency of evidence appeal, it must assume all facts were found in favor of the prosecution. Therefore, the appeal is whether "a rational trier of fact could reasonably have reached the result that it did." Jackson v. Virginia, 443 US 307 (1979). E. Jury Nullification Jury nullification is when the jury decides not to convict even when the reasonable doubt standard has been met, either because they don't want to convict the defendant or don't think what he has done should be considered a crime. Juries do have the raw power to acquit for any reason and because of Fifth Amendment double jeopardy, the accused goes free. State v. Ragland, Supreme Court of New Jersey, 1986, 105 NJ 189, 512 A.2nd 1361 Facts: Ragland, a convicted felon, was on trial for various offenses. At the conclusion of his trial, the judge instructed the jury that if it found he had a weapon during the commission of a robbery, it "must also find him guilty of the possession charge." Ragland appealed the use of "must" which he said conflicted with the jury's nullification powers. He wanted the jurors to be instructed of their nullification rights. Issue: Should a jury have been instructed that it should seek a fair result and acquit, even if the state had proved its case, in the interests of better justice (i.e., should juries be informed of their nullification powers)? Is jury nullification power an essential component of the right to trial by jury? Holding: Jury nullification is only a power, not a component of the precious "right to trial by jury." Therefore it need not be mentioned in instructions. Decision of the appellate court is overturned. Reasoning: Only one federal case supports Ragland's claim, and it is seventeen years old and has not been followed by other federal courts. It is agreed that nullification is a power of a jury, but not part of a citizen's right to trial by jury and so can be excluded from the instructions. Policy: If this is upheld, it will make it more likely that juries will nullify the law no matter how overwhelming the proof of guilt is. Furthermore, jury nullification gives legislative power to 12 randomly-selected people rather than duly elected officials. In the court's view, this should not be encouraged. The system would become impermissibly arbitrary. Notes and questions 1. Other jurists [Justice Wiseman, in United States v. Datcher, 830 F. Supp. 411] see nullification as a prime tool of the people against Government and judicial tyranny. [several cases cited here] If this is the case, then the defendant has a constitutional right to inform the jury of information that would demonstrate to them his oppression by the Government. However, these instructions have been rejected by virtually every court to ever consider the nullification issue. 2. historical precedent for nullification: noble and evil 3. Judge should inform them that they may nullify, if jury asks directly. 4. Voters in Oregon rejected a 1990 initiative that would have made the jury nullification instruction part of the state courts' instructions to juries. Justice and the law are two different things, or perhaps overlapping things but not the same thing! 5. Juries have never simply considered the law and the facts. Studies show that personality, behavior of policy, victim's role, etc, effect the decisions. 6. Race-based jury nullification. Butler, in 105 Yale LJ 677, 715 (1995) argued that juries should nullify in some non-violent cases and victimless crimes. Critics of this say that in order to nullify effectively, a jury must be given info (is person contrite? are blacks accused of this crime more often? has person committed violent crimes in past? etc) that is inadmissible at trial. CHAPTER 2 – Principles of Punishment A. Theories of Punishment 1. In general: why is punishment warranted; what are necessary conditions for punishment in particular cases; what degree of severity is appropriate for various offenders and offenses. Punishment justifications are two: retributionist (i.e., the person deserved it) and utilitarian (i.e., punishment serves a useful purpose). 2. utilitarian justifications: Bentham argues that humans are governed by pleasure or pain; thus a legislature can threaten to inflict pain only when it promotes human/societal happiness better than possible alternatives. 3. retributive justifications: according to Kant (38), guilt of a crime and punishability comes before any utility, and therefore, utility cannot be used to justify punishment. negative retributivism: wrong to punish an innocent for greater good of society positive retributivism: guilty must always be punished Morris (a protective retributionist) suggests that we have a right to be punished, since we have the responsibility to ensure that burdens and benefits in society are equally distributed (one such burden is to exercise self-restraint and not harm others; this way all can benefit from bodily security) (42ff). Hampton argues that retribution should reestablish social equality between wrongdoer and victim, with criminal's claim of superiority to victim denied by judicial mechanisms (44ff). B. The Penal Theories in Action 1. Who should be punished? Are there situations when what would normally be a crime is not a crime? Shipwrech and cannibalism case (47-48). 2. How much punishment should be imposed? People v. Du (49-55) and United States v. Jackson (55-60). If a sentence viewed by some to be too light or one viewed to be too harsh, there is no legal remedy to change the judge's freedom of sentencing (não é?) judges used to have immense discretion in sentencing; after 1987, federal and many state judges have less discretion and must follow a flow chart leading them to a narrow range of sentencing options and often removing possibility of parole (58n3). some judges employ creative punishments, such as shaming. (many of these sentences are overturned and prohibited upon appeal). C. Proportionality of Punishment -Retributive theory argues for eye-for-an-eye (cf. Kant) -Bentham argues that laws should be instituted in order to limit mischief, both in the number of acts committed and in the extent to which those acts are taken. He argues: 1. Punishment must outweigh the profit from the offence 2. the greater the mischief of the offence, the greater the punishment 3. Punishment for a greater offence should be such that it will induce a man to commit the lesser offence Constitutional principles: 8th Amend: "excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishment inflicted." In Weems v. US, the US Supreme Court ruled that this included punishments of excessive length and severity out of proportion to the offence charged. Coker v. Georgia (1977) held that the death penalty for rape is unconstitutional by the 8th Amend. Burger and Renquist, JJ, dissented on the grounds that death is disproportionate for minor crimes, but rape is not a minor crime. Harmelin v. Michigan (1991) held that 8th Amend contains no proportionality guarantee (i.e., except in cases involving the death penalty, a legislature can impose just about any penalty for any serious crime that it wants). CHAPTER 3 – Modern Role of Criminal Statutes A. Principle of Legality The relation between courts and legislatures is prescribed by three doctrines: 1. Nothing can be considered a crime without a pre-existing law 2. Statutes cannot be vague or else they are void 3. "Strict construction" which requires that judicial resolution of uncertainty in penal statutes should be biased in favor of the accused. Commonwealth v. Mochan (1955). The prosecution attempted to convict D on grounds that he had committed a common law crime (offensive phone calls) because no statute addressed what D had done. This lack of statutory prohibition was grounds for D's appeal. Court held that precedent in other cases was enough to establish that the common could indeed form basis for prosecuting offensive conduct as a misdemeanor. Dissent: This decision arrogates law-making power to courts, which is unconstitutional in Pennsylvania. Keeler v. Superior Court of CA (1970). This case shows that even in states that have abolished common law crimes, common law doctrine still has influence. The question before the court was: is killing a viable fetus in utero a murder as defined by §187: was it a "human being"?. The only task of the court was interpreting the statutory language. Court must use historical context to decide meaning of statute. Moreover, court cannot unforeseeably enlarge statute, for this would be the same as ex post facto law. Dissent: Argues that statutory language is not frozen in time but must be fairly and reasonably interpreted by the court to carry out the justice intended in the statute. In re Banks (1978). This case addresses the issue of statutory vagueness (in regards to a peeping tom statute). Definiteness of statutory language has been declared an essential element of due process of law. United States v. Foster (1998). Courts spend much time interpreting statutes. This case shows how much time can be spent on one word: "carry". Court reaches a conclusion, but adds that even if it were difficult to decide, the rule of lenity requires that ambiguity be resolved in the way most favorable to the D. CHAPTER 4 – Actus Reus Actus reus is the physical or external part of a crime; mens rea is the mental or internal. No universally accepted definition of actus reus: is it conduct (pulling trigger of gun) or the result of the conduct (death of victim)? Some offenses punish the result (murder); some punish the act (drunk driving when no one is hurt). Conduct crimes / result crimes. A. Voluntary Act Martin v. State, Alabama Court of Appeals, 17 So.2d 427 (1944) Crimes must be committed voluntarily. [I.e., fairness requires that responsibility can be assigned to an individual so that that indiv can be justly pubished.] State v. Utter, Ct. of App of Wash, 479 P.2d 946 (1971) Case seems unimportant. However, highlights issue of volition. Volition, part of actus reus, cannot occur when the accused is unconscious. That is, even if his body exhibits a behavior that results in a crime, he cannot be held culpable for it. Court cautions that voluntarily placing oneself in an unconscious state "does not attain the stature of a complete defense." B. Omissions People v. Beardsley, Sup Ct Michigan, 113 N.W. 1128 (1907) Is D guilty of death of a woman who became intoxicated under her own volition because he had a "legal duty" toward her and subsequently omitted to care for her properly? Because the deceased was a mature woman, experienced with drinking and intoxicants, and because D was not her husband and did not force her into the situation by duress or fraud, he had no legal duty toward her. Regardless of moral outrage elicited by an omission, it is ambiguous precisely because it is a non-act. Thus, it is rarely able to be prosecuted. Moreover, while an act can cause harm, an omission is the mere withholding of a benefit. Legal duty defined p. 121 n 2. Barber v. Superior Court, CA ct. of App, 2d dist, 195 Cal. Rptr. 484 (1983) Can two medical doctors be charged with unlawful killing (i.e., murder) by removing life support systems from a patient who, though in a vegetative state, maintains minor brain function? The removal of life support is not an act, but rather an omission of care (or heroic measures) and therefore there is no actus reus for homicide. This raises another issue: did doctors have a duty to continue to provide life sustaining treatment? The duty is removed once it is clear that such treatment is futile in that it doesn't sustain a life while the pathology is diagnosed, for the pathology is too severe, in this case, to be cured. C. Social Harm CHAPTER 5 – Mens Rea A. Nature of Mens Rea Regina v. Cunningham: Man steals gas meter. Gas escapes into house causing woman to be sickened. Statute requires "malicious" act to convict. Trial judge wrongly defined malicious as "wicked." Malicious should be defined as intentionality or recklessness (i.e., to foresee that harmful consequences of the act). Appellate court said D did not show intent for guilt on assault. Trial court uses culpable approach; appellate court uses elemental approach to interpretation. B. General Issues in Proving Culpability People v. Conley: Conley intended to strike Marty, but his Shaun at a party with a wine bottle causing permanent disability in boy's mouth. D appealed that under statute, he had to intend the disability, and he never did. Appeals court denies, saying that problems of proof "alleviated by ordinary presumption that one intends the natural and probable consequences of his actions." [i.e., actions reflect mental state] The above case reflects the dichotomy: normally very easy to prove actus reus, but much more difficult to prove mens rea. MODEL PENAL CODE: understand §2.02, which sets out the general definition of culpability (see also commentary on 142-145; use in forming outline) Knowledge of Attendant Circumstances State v. Nations, MO Ct of Appeals, eastern dist, 676 S.W.2d 282 (1984): By MO statute, a person can only endanger a child "knowingly". In this case, the D had not yet ascertained a child's age when she let her dance scantily clad on a stage. State argued that age of child was only attendant circumstance. Trial court convicted her of violating statute. Appeals court overruled. According to MO code, knowing requires actual knowledge of a fact, not refusal to find out. Held: D guilty of recklessness, but not knowingly endangering a child and so, by statute, she is guilty of nothing at all. Problems of Statutory Interp US v. Morris, US Ct of Appeals, 2nd Cir, 928 F.2d 504 (1991): D convicted of intentionally accessing and damaging US gov't computers via a poorly programmed worm. D argued that the damage was accidental, and so could not be liable under statute. Court studied legislative intent (for grammar analysis was inconclusive) and found that "intentionality" was not required for the portion of statute covering damages (i.e., damage is an attendant circumstance). By MPC, a MR applies to all material elements unless a specific MR is mentioned for each. Modified by any plain language that shows that something is attendant circumstance. C. Strict liability offenses Staples v. US, US Supreme Court, 511 U.S. 600 (1994): Court held that a statute making it a felony punishable by 10 years in prison for possession of a firearm not properly registered requires a culpable mens rea. Court held that the statute was a strict liability statute and so gov't must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that D knew he had a machine gun and knew it should be registered. Majority uses "common law background" to hold that only minor offenses and those not punished by imprisonment have been considered strict liability crimes. This statute too harsh without explicit legislative requirement for strict liability, the court cannot impose it. Dissent: Argues that because law has no antecedents in common law, the c. law background can't be looked to. Moreover, argues this statute is clearly constructed to protect public welfare, which places it in the class of strict liability offenses. Garnett v. State, Ct. of Appeals of Maryland, 632 A.2d 797 (1993): State argued that Maryland's statutory rape law was a strict liability offense. Garnett, a mentally retarded man, argued for engrafting of a mens rea requirement which might be used to excuse him on grounds he had no "vicious will" in this case. After stating that some commentators abhor strict liability, court holds that the statute in question is a strict liability offense and has no mens rea requirement and D's can only rely on forebearance of trial judges to limit their penalty. Dissent: The heavy penalty for statutory rape implies the legislature had some mens rea intent. (this fits with Staples v. US). D. Mistake and Mens Rea 1. Mistake of Fact People v. Navarro (1979): D convicted of theft. He appealed that jury improperly instructed. D argues that if he took object in mistaken belief (mistake of fact) that it was his, he did not have the proper mens rea (this is a specific intent crime) to commit theft and should be acquitted, even if his belief was unreasonable). Appeals court reverses saying that if D's belief was genuine, then he cannot be convicted no matter how unreasonable his belief was. [Nevertheless, if a jury believes that D's belief was unreasonable, it may vote to convict because it does not believe he acted in good faith.] 2. Mistake (or Ignorance) of Law People v. Marrero (1987): After final appeal, D was not allowed to claim that he misunderstood the statutory definition of peace officer (which led to his conviction of carrying an unlicensed firearm) and claim excuse under NY's "mistake of law" statute. D's conviction upheld because the statute he violated was a strict liability statute and therefore "mistake", even a reasonable one, is not an excuse when there is no mens rea specified by a statute. [Another applicable situation is when the "misrelied-upon law has later been properly adjudicated as wrong.] Dissent: As mens rea has increased in importance in the common law, the refusal to permit mistake of law defense has grown foolish. "It is simply wrong to punish someone who, in goodfaith reliance on the wording of a statute, believed that what he was doing was lawful." Cheek v. US US Supreme Court (1991): Anti-tax crusader convicted of willfully evading taxes. Willfulness defined as "the voluntary, intentional violation of a known legal duty." Steps to convict on willfulness: 1) law imposed a duty on D; 2) D knew of that duty; 3) D voluntarily and intentionally violated that duty. One cannot know that the law imposes a duty (e.g., you must pay taxes as defined by law) and then claim to misunderstand the law or believe the duty does not exist. US Supreme Court held that a good-faith belief need not be objectively reasonable to claim mistake of law defense (unreasonable belief defense allowed when a mens rea is required in a specific intent case such as this). Cheek's defense fails for another reason, that he knew he had a duty to pay taxes, but claimed it was unconstitutional. CHAPTER 6 – CAUSATION Intro Velazquez v. State, Florida (1990): Causation-in-fact test: occurrence of a specified result is caused by D's conduct. [useless case] A. Actual Cause (cause-in-fact) Oxendine v. State, sup ct of Del (1987): Oxendine's conviction of manslaughter for beating son to death overturned due to lack of evidence showing that his beating was the death beating of a child that was beaten by numerous people! I.e., his actions could not be shown to be cause-infact of child's death. Conviction affirmed on lesser included charge of 2nd-degree assault. Held that lethal injury inflicted 24 hours before non-lethal injury inflicted by Oxendine. B. Proximate casue ("legal" cause) Kibbe v. Handerson (1976): Procedural: Kibbe appealed a motion denying his writ to habeas corpus charging that the trial judge failed to charge the jury with respect to the causation of death on the murder cournt. Appellate court affirmed conviction on grounds that victim's death caused by Kibbe's acts as well as those of Blake. Sup Ct court held: jury instructions permitted jury to disregard Kibbe's claim that he did not cause the death and thus violated constitutional right to have every element of crime determined beyond a reasonable doubt. Facts: Kibbe and co-D took drunk man in car and robbed him. They left him on the side of a road during a cold night and without his glasses. He was within 1/4 mile of a gas station. Thirty minutes later, Michael Blake, college student going 50 in a 40 zone, struck and killed victim. Autopsy found victim died from injuries sustained; therefore Blake is actual cause. Reasoning: Kibbe convicted for recklessly endangering human life and causing death; intent not required under statute. Judge failed to instruct jury on "causation" as it related to the statutory language and did not mention the legal effect of intervening or supervening cause. e.g., a coincidence will break the chain of legal cause unless it was foreseeable "any intended consequence of an act is proximate": i.e., if wrongdoer gets what he wants, even if it didn't happen as planned, he will not escape criminal liability. apparent safety doctrine: when a person reaches a position of safety, the original wrongdoer is no longer responsible for the ensuing harm (p. 206) the criminal law does not hold a person responsible for resulting harm if there is an intervening cause that springs from "free, deliberate and informed" human action (i.e., once a voluntary human action is discovered, the law will not trace back the causal chain any further). Do problems on pp. 206-208 and understand MPC discussion of causation. C. Concurrence of the Elements State v. Rose (1973) Procedural: D convicted of leaving scene of accident resulting in death and negligent manslaughter. Motions for a new trial denied. D claims it was error to deny a directed verdict of acquittal on both charges. Supreme Ct of RI holds that leaving the scene was fairly tried, but D should have received a directed verdict of acquittal on manslaughter charge. Facts: Rose hit victim, stopped car momentarily as body rolled off, and then sped away. Body of victim actually wedged underneath the car. Reasoning: Because the medical examiner cannot conclude with certainty that victim did not die immediately after being struck by the D's car, it is not possible to determine beyond a reasonable doubt that he caused death by dragging (which would be negligent manslaughter). Ergo, D must be acquitted on manslaughter charge. [NB: with Oxendine and this case, medical testimony is of the utmost importance.] CHAPTER 7 – Criminal Homicide Crime analysis steps: 1) what does statute require? 2) how are terms (willful, premed, etc) defined by statute? 3) what do facts say? Intentional Killings Deliberation-Premeditation State v. Schrader (1982) Procedure: D found guilty of murder in 1st degree, sentenced to life in prison. D appealed based on jury instruction that said premeditation could occur instantaneously before killing, not at a previous time. D argues this takes the "pre" out of premeditation. Appeals Court disagreed. Facts: D argued with man over authenticity of German sword he had purchased. D stabbed victim 51 times all over body and claimed to have acted in self-defense because victim was known to carry guns and D thought he was about to draw one. Reasoning: Such an interp – of premed being instantaneous – was fair to legislative intent when the W. Virginia statute was codified in 1868 and precedent also upholds it. In this state, premeditation is essentially "knowing" and "intentional." Midgett v. State (1987) Procedure: D appealed, on basis of lack of facts, a conviction of 1st degree murder resulting from child abuse. Court held that facts did not sustain 1st degree murder but did sustain a conviction of 2nd degree murder. Facts: D constantly beat his son. A beating on Saturday, a result of lots of drinking by D, killed the boy by Wednesday. Boy had died of blunt-force trauma to abdomen caused by human fist resulting in internal bleeding. Reasoning: Court agrees with D that while he was a child abuser, he did not premeditate the killing of his son. [Court states that even if D did develop intent to kill son, it was done in a drunken rage, which does not support finding of premeditation.] State v. Forrest (1987) Procedure: D convicted of 1st degree murder of his father and sentenced to life. D appeals on the denial of his motion for directed verdict of acquittal on 1st degree charge, alleging that there was insufficient evidence of premeditation and deliberation. Court disagrees and affirms verdict. Facts: D's father had been ill for a long time. He was admitted to a hospital, signed a waiver foregoing heroic measures to save him, and was in some pain. D killed father in what he seemed to see as a mercy killing. Reasoning: Premeditation and deliberation are not readily susceptible to proof by direct evidence, but rather must be proved by circumstantial evidence (six such criteria are listed). That is, by objective manifestations of said mental state, including actions and words. Girouard v. State (1991) Procedure: Girouard convicted at trial of 2nd degree murder, despite finding of some provocation though not enough to mitigate charge down. D appeals saying that it should have been manslaughter in that he was provoked with hurtful words from his wife. Argues that manslaughter should be a catch all for "homicides which are criminal but that lack the malice essential for a conviction of murder." Held: trial verdict affirmed. Facts: Wife told him he was bad at sex, she didn't love him, and she was trying to have him court-martialed. Girouard killed wife after hearing all this and then tried to kill self. Psychologist testified that Girouard killed in an explosion of rage caused by inability to bottle up any more anger. Reasoning: To determine if there was provocation, we must use the "Rule of Provocation": 1) there must have been adequate provocation; 2) killing must be in heat of passion; 3) must be a sudden heat – i.e., killing must directly follow provocation, not be done after a period of cooling; 4) need causal connection between provocation, passion, and fatal act. For words to constitute adequate provocation, they must be accompanied by conduct indicating present intention and ability to cause the D bodily harm. [i.e., words alone are not enough]. Added that the standard here is reasonableness, not focusing on frailty of D's mind [i.e., shrink testimony useless]. Director of Public Prosecutions v. Camplin (1978): Procedure: D's lawyer wants jurors to use reasonable boy standard but trial judge says it must be a reasonable adult. Jury convicts Camplin of murder. Issue on appeal: should D be judged as boy or man? Held: Age does affect behavior and a jury should be permitted to take it into account. Facts: Khan buggers Camplin and then laughs at him. This enraged Camplin who killed Khan by hitting his head with a cooking pan. Reasoning: Defines reasonable man (see outline). People v. Casassa (1980) – MPC Procedure: D appeals that he asserted a defense of "extreme emotional disturbance" that should have been taken into account at trial and reduced his murder conviction to manslaughter. D claims that his situation should have been viewed on a wholly subjective standard, rather than the objective reasonable man test. Appeals court held that this is not possible and conviction affirmed. Facts: Ms. Lo Consolo informs D she was not falling in love with him in Nov. 1976. D claims he was devastated. D claims that eavesdropping and break-ins were evidence of his emotional distress. D finally kills her in Feb 1977 when she refused to accept gifts of wine and liquor. Reasoning: D's psychiatrist argues that D had become obsessed with victim and that combined with several of D's peculiar personality traits to lead to the emotional distress and killing. Finally: Is D's subjective perception one that, if a reasonable man had it, would lead to the same action? This means that jurors will have to use their own judgment, but this seemed to have been the intent of the legislation. D. Unintentional Killings: Unjustified Risk-Taking Berry v. Superior Court (1989) Procedure: Berry charged with murder of 2 1/2 year old boy who was killed by Berry's pitbull. Berry seeks dismissal of charge claiming the evidence falls "legally short of establishing implied malice sufficient to prosecute him for murder." Held: evidence shows possibility of implied malice. Facts: Berry's dog tethered outside, but no barrier prevented access to dog's area. The boy's family lived on the same lot and shared a common driveway. Unsupervised child wandered off and was attacked by the dog. Berry stopped attack as soon as he learned of it. There was evidence the dog had been trained to fight. Berry had previously told boy's mother that the only dangerous dog was Willy, the said pitbull, but that he was behind a fence. Reasoning: Test for implied malice: 1) D's extreme indifference to the value of human life to be demonstrated by showing the probability that the conduct involved will cause death and 2) awareness of either (1) the risks of the conduct or (2) that the conduct is contrary to the law. Test 2: Berry kept a dangerous, illegal fighting dog and used the dog also to guard illegal marijuana plants. Test 1: Berry knew his neighbors had four small children, knew Willy was dangerous to people, Berry lulled boy's mother into false sense of security about harmlessness of dogs. State v. Hernandez (1991) Procedure: At trial, D found guilty of involuntary manslaughter. On appeal D argued that drinking slogans and stickers attached to his van were inappropriately admitted into evidence. Held: conviction reversed. Facts: Hernandez was drunk and crashed into a car, killing one of its passengers. Reasoning: Evidence is relevant if it logically tends to support or establish a fact or issue. Elements required for involuntary manslaughter are: 1) D acted with criminal negligence and 2) these actions caused the death in question. Drinking slogan's used to assault D's character and prove he knew the effects alcohol had on him, i.e., had nothing to do with material elements of the charge. Dissent: Under MPC, jury is to decide if D failed to perceive that he was engaged in a "gross deviation" from the reasonable person standard of care. Thus, three of the slogan's did show that he knew the effects of alcohol on him and therefore should have been admitted in evidence. State v. Williams (1971) Procedure: D's found guilty of manslaughter for negligently failing to supply their 17-month old child with medical care resulting in his death. D's appeal. Conviction affirmed. Facts: D's knew the baby was sick, but thought it had a toothache. One reason they did not take the baby to a doctor was out of fear that the welfare dept might take the baby from them. Reasoning: Although CL required "gross negligence" for involuntary manslaughter, statutory law requires merely simple or ordinary negligence. Since D's negligence held to be the proximate cause of baby's death, we must determine when the duty to furnish medical care became activated (i.e., it must have been while baby still had a chance to live) while it was capable of being the proximate cause. E. Unintentional Killings: Unlawful Conduct 1. Felony-Murder Rule a. the doctrine in its unlimited form People v. Stamp (1969) Procedure: Facts: Man dies from heart attack brought on by the stress of an armed robbery. Reasoning: Felony murder rule applies whether deal was willful and premeditated or if it were accidental. Doctrine is not limited to those deaths that are foreseeable. People v. Fuller (1978) Procedure: Facts: Men flee from cops in a high speed chase. Men crash into another car and kill the driver. the felony murder rule applies. Reasoning: Court says that both precedent and statute require the application of the rule. However, they argue that were they writing the legislation, it would not apply in a case like this. b. the policy debate c. Limitations on the Rule i. The "inherently dangerous felony" limitation People v. Burroughs (1984) Procedure: Trial court held that felony-murder rule applied because practicing medicine without a license was "an inherently dangerous felony." Appeals court reverses as a matter of law. Facts: Man has cancer and seeks alternative healing. D is the unlicensed medical practitioner. Evidence presented that massages performed by D caused internal bleeding and death of man with cancer. Reasoning: By policy, if a felony is not inherently dangerous, then the felony-murder rule would not deter a felon because he would not anticipate causing death. We must look at two things to see if a felony is inherently dangerous: 1) what is the primary element of the offense? [in this case, treating the sick – no inherent danger] and 2) what raises the offense to a felony? [when the act causes great bodily injury, severe mental or physical illness, or death. Since death listed separately, legislature assumed that the felony could be committed without death resulting]. In other words, the statute against unlicensed medical practice can be violated "without creating a substantial risk that someone will be killed." [NB: CA court interprets felonies in the abstract; many states look at individual facts of each case to make the determination on inherent dangerousness.] ii. the "independent felony" (or merger) limitation People v. Smith (1984) Procedure: Facts: Mother beats child and is joined by man she lived with. Child is knocked over and kits head on closet. She dies as a result. Reasoning: skipped some entries Gregg v. Georgia (1976) US Supreme Court Procedure: Facts: Reasoning: essentially a policy debate among the justices of the US Supreme Court over the validity of the death penalty 1. Does death for murder violate 8th Amend against cruel and unusual punishment? is there a lack of proportionality, is it excessive? -deterrence = equivocation -retributive = a valid theory, but must be tempered by process so that visceral moral outrage will not condemn people to death out of hatred/anger -public opinion – if it supports death penalty, then can be used to support its continuous usage 2. does the procedure with which it is applied render it ligitimate? Yes -application of an automatic death penalty would be unconstitutional -application of death must be based on aggravating and mitigating factors Tison v. Arizona (1987) US Supreme Court (exam question type of case; prof says don't worry about this issue on the examination) Procedure: Tisons appeal their death sentence on constitutional grounds since they did not participate in the actual murders and had been convicted under the felony-murder rule. Held: affirmed. Facts: People escape from prison. After they are out, they flag down a car and kill the occupants. Two of the people who aided the escape, the Tison brothers, were not in the area and did not participate in the killing. Reasoning: Main issue: whether the 8th amend against cruel and unusual prohibits death penalty when a D is a major participant in a felony, but merely has mens rea of reckless indifference to the value of human life? No, death penalty is okay if you show 1) major participation and 2) an independent mens rea with respect to the death. (if they were only tangentially involved, then death penalty would be disproportional). NB: court here seems to be assuming/inventing a mens rea for the killing, for prosecution never had to prove a mens rea under felony-murder rule at trial. US Supreme Court says, juries can infer mens rea for purposes of sentencing even though not proven at trial. RAPE historically, under common law, woman almost required to resist or attempt to flee, otherwise it was assumed that she consented to it. (compare: a murder victim does not need to try to run away before we impose punishment on a murderer). CL: show separate showing of identifiable force resistance lack of consent against your will - does man who does not intend to have sex without consent have the mens rea for rape if he honestly believes woman has consented - does a man who persuades a woman through cajoling have a mens rea for rape? MPC: mens rea to have sex without consent (§ 213.1) lessens prosecutorial burden (but does this raise due process issues for D?) Actus Reus Rusk v. State (1979) Procedure: convicted at trial. Reversed Facts: Reasoning: Force is an essential part of the crime. Evidence must warrant a conclusion either that the victim resisted and her resistance was overcome by force or that she was prevented from resisting by threats to her safety. In order for a rape trial to get to jury, the trial judge must find as a matter of law that there is evidence for the jury to find the victim was reasonably in fear. Dissent: This interpretation, requiring resistance on the part of the victim, leads a rape judge to focus on the acts of the victim rather than the criminality of the acts of the accused! Argues that the real test of rape should be "whether the assault was committed without the consent and against the will of the prosecuting witness," for after all submission (i.e., lack of physical resistance) is not the equivalent of consent. State v. Rusk (1981) Supreme Court of Maryland reinstates the conviction, mainly following the reasoning of the dissent in the above case. The issue becomes: was her fear reasonable? Most states still apply a Rusk doctrine requiring at least some physical resistance, though not the traditional "utmost resistance." However, if women believed that resistance would lead to great bodily harm, then she need not resist. Resistance Rule: 1) communicates a lack of consent and 2) man must therefore use force to overcome the resistance State v. Alston see outline Since victim know that Alston had potential for violence (based on their prior relationship), does knowledge of this potential mean that she could have inferred threat? Cf. knowledge of an attackers rep for gun violence is relevant to reasonableness of use of deadly force for selfdefense Traditional rape statute: sex can be against a woman's will but in the absence of force, it is not rape! This appears to be a paradox. In effect, the law has chosen to celebrate male aggressiveness and punish female passivity (383). Rape seems to have originally been deemed an offense in order to protect the property rights that men had over their wives and daughters which placed the burden of protecting their chastity on the women themselves (399). Rape is underreported to police for lots of reasons, but one that seems to predominate is that both society and rape victims themselves assign some of the blame for the sexual assaults to the victim. Both society and (at times) the victim wonder if she did something to bring it on herself. (see page 381). d. "No" (or the absence of "Yes") as Force? Acquaintance Rape Case #1 Commonwealth v. Berkowitz Procedure: Trial court: D was convicted of rape and indecent assault. D's appeal: while D may have engaged in poor social conduct, it was not criminal. V even admits that D never hurt her or threatened her and she never screamed or summoned held. [i.e., does not meet some of the legal requirements of Actus Reus]. State counters: the only real important part of Actus Reus is lack of consent. HELD: Reversed. Facts: Two college students. D straddled victim, never used violence, but exercised his power over victim. Victim said "no" repeatedly, but he never listened. She did not physically resist or scream out. Defense lawyer tries to attack V's character and paint her as a sex tease. D claims that he thought, by V's actions prior to incident, that she wanted to pursue a sexual relationship with him; i.e., there was consent. [thus, by attacking her character, it makes the jury believe the story of D more than the version of V, who people will just figure is a horny young woman] Reasoning: Court lists a series of factors one can consider to see whether force was used in the rape. Among others, they list the ages of the parties and the setting and atmosphere where the incident took place. Court says that: the setting where the incident took place was in no way coercive, D not in position of authority over V, and victim was under no duress. V said at trial that D had never threatened her. Finally, under existing statutes, saying "no" is not enough to uphold a conviction of rape. Saying "no" expresses a lack of consent, but does not by itself establish "forcible compulsion." Case #2 State of New Jersey in the interest of MTS Procedure: ISSUE: does the act of penetration itself constitute physical force to meet the definition of 2nd-degree sexual assault? Trial court says yes, appellate court reverses, and Supreme Court reverses and upholds trial verdict. Facts: Girl says boy was always trying to get some action, but she didn't want any. Girl says she woke up with boy's penis inside of her. Boy says they had kissed previously and had discussed having sex. Boy says they had consensual sex for a few seconds, and then she pushed him off and he stopped. Reasoning: Current judicial practice suggests understanding "physical force" to mean "any degree of physical power or strength used against the victim, even though it entails no injury and leaves no mark." NJ statute meaning of "physical force" has no plain meaning; therefore, must go to legislative intent and rule of lenity. NJ statute does not relate force to overcoming will of victim or getting victim to submit, that is, it does not require the demonstrated non-consent of the victim. It seems the legislature analogizes rape with assault and battery laws: "the unlawful application of force to the person of another." Consequently, sexual assault in NJ is defined by the court as "any act of sexual penetration engaged in by the D w/o the affirmative and freelygiven permission of the V to the specific act of penetration." Lack of consent is all that matters. However, permission/consent may be inferred from acts or statements reasonably viewed in light of the surrounding circumstances. 2. Deceptions and Non-Physical Threats Boro v. Superior Court Procedure: CA prosecutes D on theory that V was unconscious as to the "nature" of the sex act (i.e., it was rape, but she thought it was a medical procedure). HELD: statute not applicable as CA holds that fraud in the inducement to engage in sex does not vitiate the consent that was then freely given. Facts: D convinces woman that she must have sex with him in order to save his life. She calims that as she thought her life was in danger, she submitted. Reasoning: If consent had been given to something other than sex, and then sex resulted, then the statute would be applicable. In the absence of threatening words or actions, fear as an inducement to have sex cannot, as a matter of law, lead to a conviction on a rape charge. But if we equated sex with money for purposes of legal analysis, then inducing fear to acquire money is a crime. B. Mens Rea Commonwealth v. Sherry Procedure: Ds charged with kidnapping and aggravated rape, but only convicted on lesser included offense of rape without aggravation. Ds claim jury instruction prejudiced them. They claim to have made a good faith mistake of fact, arguing that they thought V had given consent. HELD: jury instruction were proper; affirmed. Facts: Doctors take a woman to a house; engage in sex with her after she tells them to stop. They do not physically force her and she doesn't resist because she felt numb, humiliated and disgusted. Reasoning: Mistake of fact can only be claimed as a defense when the "accused act in good faith and with reasonableness." General judicial belief: if a D entertains a reasonable and bona fide belief that V voluntarily consented to sex, then he does not possess wrongful intent that is a prerequisite for rape. A small number of courts hold that mistake of fact is no defense, analogizing it to the strict libability of statutory rape cases where mistake of V's age is not defense. C. Proving Rape 1. Rape Shield Laws People v. Wilhelm Procedure: D. convicted of sexual assault. D appeals, arguing that evidence of V's sexually provocative behavior earlier in public in a bar should have been admitted in evidence. HELD: No, judgment affirmed. Facts: V showed breasts and allowed herself to be fondled by various men in a bar. The D witnesses this. V went voluntarily with D to his boat where they had sex. V claims it was nonconsensual. Reasoning: Even public acts need not be admitted. Statute does not distinguish between public or private acts. Next, court does not see how a V's consensual sexual activity with one person indicates to a third-party that she would be sexually open to him. CHAPTER 9: GENERAL DEFENSES TO CRIMES B. Burden of Proof Patterson v. New York: issue – what does court mean by "fact" in the Winship decision that said due process requires that factfinder be persuaded "beyond a reasonable doubt of every fact necessary to constitute the crime charged"? Does this include every element of crime as set out in the definition? Must it prove the absence of any defenses for D's conduct? NY statute did not shift burden of disproving intent to D; also, it is not unconstitutional to put the burden of production on Ds for affirmative defenses and also the subsequent burden of persuasion (meanwhile, prosecutor has burden of production for the elements of the crime)(450n1). Procedure: Court of appeals held: NY statute constitutional because affirmative defense goes to proving an element not part of the statutory definition of crime with which D charged (i.e., not a material element). US Supreme Court HELD: affirmed. Facts: Patterson shoots wife's lover in head with rifle. Charged with 2nd degree murder. Two statutory elements to crime of 2nd-degree murder: 1) intent to cause the death of another person and 2) causing the death of such person or of a third person. Affirmative defense of "extreme emotional disturbance" to be proven by preponderance of evidence is permitted under statute to mitigate down to manslaughter. Reasoning: ISSUE: Is it constitutional under the 14th Amend's Due Process Clause to burden a D with proving an affirmative defense of extreme emotional disturbance in defense of a murder charge? At common law, burden of proving any affirmative defense rested with D. The affirmative defense in this case does not serve to negative any facts the State needed to prove under statute, but rather is a separate issue the D can use to benefit himself. State not required to prove the existence or nonexistence of mitigating or exculpatory circumstances that it is willing to recognize by statute. Policy: Reasonable doubt burden of proof founded on policy that it is better to let a guilty man go free than put an innocent man in jail. However, society must not be made to bear a burden to great, for holding the State to prove or disprove mitigating or exculpatory circumstances beyond a reasonable doubt would be nearly impossible. DISSENT: This holding allows a state legislature to shift the burden of proof to Ds at will, so long as the element is not mentioned anywhere in statute except in the affirmative defense section. Should State have burden? Two-pronged test: 1) does factor make a substantial difference in punishment or stigma? and 2) has that factor held a historically high-level of importance in our legal tradition? If one of these factors is not met, then legislature has authority over matters of proof. Principles of Justification Self-Defense US v. Peterson Procedure: Peterson charged with 2nd-degree murder and convicted on manslaughter. Appeals that jury instruction were in error on two grounds: 1) instructing jury that Peterson may have been aggressor in fight that preceded homicide and 2) instruction on the failure to retreat. HELD: trial conviction affirmed. Facts: V tries to steal wiper blades from D's car. D gets pistol and tells V not to move. V gets wrench and approaches D. D tells V not to approach or he'll kill him. V approaches and D shoots V dead. D claims self-defense. Reasoning: "The law of self-defense is the law of necessity;" the right of self-defense arises only when the necessity begins and equally ends with the necessity. Moreover, the necessity must appear to offer no alternative to taking life. Aggression: aggressor normally can't assert selfdefense; one cannot support a claim of self-defense by a self-generated necessity to kill. Retreat: under common law, there was a duty to "retreat to the wall" before you use deadly force. People v. Goetz Procedure: Should self-defense justification be based on a purely subjective standard, or should the actions of a D be weighed according to that of "a reasonable man in Goetz's situation"? Trial court thought it should be subjective and tossed charges. Appellate affirmed. HELD: reversed and charges reinstated. Facts: Goetz shoots four boys who asked him for $5 while he was on a subway train. None of them brandished a weapon. Goetz admitted having carried the illegal handgun for over three years. Goetz admits that he knew none of the youths had a gun, but that he feared being "maimed" by their attempted robbery. By his own admission, Goetz wanted to inflict death or grave injury. Reasoning: Using physical force for self-defense is justified, by statute, when actor reasonably believes that such force is necessary to defend himself (or a third person) from what he reasonably believes to be the use or imminent use of unlawful physical force. Actor may use deadly force if he reasonably believes the other is using or will use deadly force, or if other is planning a kidnapping or forced sex crime or robbery. Penal statutes in NY have never required that a D's belief as to the intentions of another be correct, only that the belief is objectively reasonable given the circumstances. State v. Wanrow Procedure: D convicted of 2d-degree murder. She appeals conviction. HELD: reversed due to serious error at trial. Facts: Neighborhood molester/pervert discovered by Ms. Hooper to have molested her daughter. Creep suspected of having attempted to break into Hooper's house. Wanrow, Hooper's friend, came over to spend night at house and brought her pistol after hearing all the details about the creep. Two neighborhood men confront creep and creep says, let's go over to Hooper house and straighten things out. Creep entered; shouting occurred; creep startles Wanrow, and she shoots in a "reflex" action, killing creep. Reasoning: error #1: Jury instruction told jury to only evaluate circumstances "at or immediately before killing." Wrong, Washington law permits all relevant circumstances, even those that occurred substantially before killing, to be considered by jury. error #2: instructed jury on an objective standard for D's appraisal of circumstances, but Washington law permits subjective beliefs of D (based on gender, size, age) to be considered. State v. Norman (appeals court) Procedure: D convicted of murder at trial. HELD: trial court erred in failing to instruct jury on self-defense. New trial granted. Facts: Woman beaten all day by husband. She went to mother's house, got a .25 caliber, returned home, loaded gun, shot husband while he slept. Psychologists testify that wife beating had become torture; D living an animal's existence and thought she had no means of escape and no other options to end the torture. Psychologists testified that D suffered from "abused spouse syndrome." Reasoning: Did V's passiveness at moment of killing preclude a self-defense justification for the killing? No. Self-defense has subjective and objective elements. Subjective: did individual D feel it was necessary to kill in order to save herself from death or serious bodily harm? Objective: would a person of ordinary firmness in the same circumstances as D come to a similar conclusion? Policy: a battered person (who is truly and extensively battered) need not wait until the moment a deadly attack comes or even be in the process of enduring an attack to be justified in killing in self-defense. State v. Norman (supreme court of NC) Procedure: HELD: appeals court reversed. Facts: Reasoning: Evidence in this case would not support a finding that the D killed her husband due to a "reasonable fear of imminent death or great bodily harm." The supreme court focuses on the word imminent. (Appeals court had focused on the harm itself.) policy: to permit killing based on speculations as to future acts would permit homicidal self-help for any woman who is depressed and claims a history of abuse and subjectively viewed her life as bad. Dissent: The proper question is not whether the harm is imminent, but rather the D's belief in future harm was reasonable to a mind of a person of ordinary firmness. Commonwealth v. Martin Procedure: D convicted of various assaults. D appeals on failure of trial judge to instruct jury on his defense of others justification. HELD: instruction should be given to jury Facts: Prosecution version: D was freed from cell by an inmate who had stolen keys after a fight and then D rushed to join a general assault on guards. Defense version: D was let out of cell, and intended to return to cell when he heard his friend scream for help. He saw friend being beaten mercilessly and D had no idea how altercation started. D then raced over, hit guards to protect friend. Reasoning: D's evidence was sufficient to require judge to charge jury with justification defense (though it was up to jury to decide whose story to believe). People v. Ceballos Procedure: D convicted of assault with deadly weapon. D appeals, contending his conduct was legal because he was protecting his property from burglars with use of a trap gun. HELD: judgment of trial court affirmed. Facts: D set up trap gun. Boys tried to break in to garage, likely to steal some musical equipment. One boy hit in face with bullet. Neither boy was armed with deadly weapons. D admits to setting trap to protect property. Reasoning: Trap guns are always prohibited with one tort exception: if D had been present and would have been justified in using deadly force, then the firing of the trap gun is also justified. Court refuses to apply such a standard to criminal conduct Commonwealth v. Leno Procedure: Ds convicted of unauthorized possession of instruments to administer controlled substances and unlawful distribution of said instruments. Ds appeal on judge's refusal to instruct the jury on the defense of necessity. HELD: affirmed. Facts: Ds operated a needle exchange program contract to Mass statute that requires needles to be distributed only with a prescription. Ds claimed that they broke the law as a matter of conscience in order to help prevent deaths from AIDS. Reasoning: Defense of necessity does not apply here because it is limited to four circumstance: 1) when D is faced with a clear and imminent danger; 2) D can reasonably expect his actions will abate the danger; 3) no legal alternative will be effective in abating danger; 4) Legislature has not acted to preclude the defense. Key for the court is the imminence requirement. US v. Schoon Procedure: Convicted of obstructing activities of IRS and failing to comply with an order of a federal police officer. Appeal that they were entitled to a necessity defense (for civil disobedience). HELD: affirmed. Facts: Broke into IRS office, chanted "keep tax dollars out of El Salvador", and splashed fake blood around. They ignored an order to disperse and were arrested. Reasoning: Could be affirmed because 1) there was no immediacy of harm, 2) actions taken would not abate evil, or 3) other legal alternatives exist. however, court chooses to affirm because indirect civil disobedience involves violating a law or interfering with gov't policy that is not itself the object of protest. Therefore, there is no DIRECT attempt to prevent the harm and therefore action can not be said to stem from necessity to prevent harm. US v. Contento-Pachon Procedure: Convicted at trial of unlawful possession with intent to distribute a narcotic controlled substance. Evidence for duress and necessity defenses excluded on ground there was insufficient evidence to support the defenses. HELD: reversed in part; there was enough evidence for duress to be a triable issue. Facts: D claims that he was forced to swallow ballons filled with cocaine and traffic them to US from Columbia or else his wife and child would be killed. Reasoning: A duress defense has three elements: 1) immediate threat of death or serious bodily injury 2) well-grounded fear that the threat will be carried out 3) no reasonable opportunity to escape the threatened harm Necessity vs. Duress People v. Unger Procedure: Convicted by jury of escape. D appealed on basis of trial judge prohibiting any justification or excuse defense for his escape. Reversed on appeal. HELD: affirmed. Facts: Unger was serving time for auto theft. He served time in Joliet where he was threatened with SBI if he didn’t participate in homosexual activities. He never reported the threat. He was later transferred to honor farm. At honor farm, he was sexually assaulted by three inmates. He was then threatened with further assaults and, on the day he escaped, death because someone heard he had reported the assaults. While at a minimum security honor farm, he walked off the grounds. He was apprehended two days later. Reasoning: Duress not applicable here because no demand for escapee to perform the specific act for which he was eventually charged and the "coercing party" is not guilty of the crime. This case is better viewed through the lens of necessity defense. Wrongfulness in the Insanity Plea State v. Wilson Procedure: Jury rejects insanity defense and convicts D of first degree murder. Facts: D was crazy and thought V was part of a mind-control group that had it out for him. Reasoning: Two issues: 1) how should wrongfulness be defined for a jury instruction in the insanity defense? and 2) should such an instruction have been given in this case? 1. D lacked substantial capacity to appreciate the wrongfulness of his actions if, at time of act as a result of mental disease or defect, "he substantially misperceived reality and harbored a delusional belief that society, under the circumstances as the defendant honestly but mistakenly understood them, would not have morally condemned his actions." (subjective/objective hybrid). Policy: If we were to define wrongfulness on a purely personal standard, it would undermine "the moral culture on which our societal norms of behavior are based." 2. Based on expert testimony, court concludes that there was enough evidence for a jury to reasonably conclude based on preponderance of the evidence that D had the mental disease element which led to apprehensions as set out in point 1. Dissent: this is a bullshit instruction: if the D recognizes his conduct is both criminal and wrong in the eyes of society, public safety demands that he be held responsible for his actions. State v. Green Procedure: HELD: state's rebuttal evidence not sufficient to refute proof of Green's insanity. Facts: Green is clearly a freak and had been since childhood. At 18, he was charged with murder of a police officer. His appointed attorney immediately saw his craziness and asked for a psychiatric exam, which the court granted. Dr. Speal diagnosed Green as a paranoid schizophrenic. Green soon was found incompetent to stand trial, but later improved after hospitalization and a trial was ordered. Trial experts: no experts were offered by the State to refute insanity of Green during period when murder occurred. Reasoning: Even though some witnesses engaged in interactions with Green said that he seemed "normal, but a bit quiet" when they encountered him is not inconsistent with holding that Green was insane at the time of the offense. Due to this evidence, burden shifted to State to prove Green's sanity beyond a reasonable doubt. State v. Wilcox Procedure: jury rejected insanity defense. Trial judge refused to permit evidence for diminished capacity to negate MR req for murder and burglary. Facts: Court shrink found Wilcox to be borderline retarded and schizo. Reasoning: Court believes that diminished capacity is stupid. First, insanity already recognizes the line between those who can form the intent to commit a crime and those who can't. The law does not recognize what the diminished capacity defense would have it do: that among those who are not insane, individual mental capacity varies greatly. CHAPTER 10: INCHOATE DEFENSES MR People v. Gentry Bruce v. State felony murder requires no specific intent to kill THEREFORE attempted felony murder cannot be a crime because criminal attempt is a specific intent crime AR US v. Mandujano People v. Miller attempted murder; not guilty because act of loading gun and standing near threatened victim is deemed Aequivocal.@ (Controversial decision). in order to draw the line between preparation and perpetration, the D must have committed a direct (unequivocal) act toward consummation of the crime. Statements made by actor before and after the act are not necessarily reliable indicators of intent because actor may have been bluffing or merely entertaining the act State v. Reeves good case for application of the MPC test and def of Asubstantial step@ substantial step: 1. Conduct is strongly corroborative of the actor=s criminal purpose 2. Some acts that, if strongly corroborative, which are sufficient for substantial step: a. possession of materials to be employed in the crime and are specially designed for the crime or can serve no lawful purpose to actor under the circumstances b. collection, possession, or facbrication of materials at or near place of commission of crime if such cannot serve lawful purpose to the actor substantial step test (put in line of tests in outline) (5.01(2)) a. possession of materials to commit crime and can serve no lawful purpose b. possession at or near place of commission that can serve no lawful purpose c. lying in wait; searching for victim d. enticing or seeking to entice victim to intended spot of commission e. reconnoitering the place contemplated for commission of crime f. unlawful entry into place where contemplated to commit crime g. soliciting an innocent agent to engage in conduct constituting an element of the crime proximity tests focuses on what remained to be done vs. substantial step focuses on what had already been done (broadens scope of liability though does not impose liability for relatively remote preparatory acts); no finding required as to whether actor would have probably desisted in the commission of crime After entering all of this into my outline, go back to pp. 731-733 and apply all the tests as asked in the examples. Punishing Pre-Attempt Conduct US v. Alkhabaz case talks about establishing AR for a statutory provision AR can be determined by examining the nature of a threat. Threats are leveled in order to achieve some effect or goal through intimidation. Threat B a communication objectively indicating a serious intention to inflict SBI (MR) B communication is also conveyed for the purpose of furthering some goal through the use of intimidation (AR) - must intimidate person to whom threat is directed Special Defenses to Attempt a. Impossibility US v. Thomas raped a woman, but she was DEAD, but they didn't know it b. Abandonment Commonwealth v. McCloskey CONSPIRACY although it is an inchoate offense, it is a basis to hold someone accountable for the completed crimes of others (co-conspirerors).