Race, Citizenship attached - Immaculateheartacademy.org

advertisement

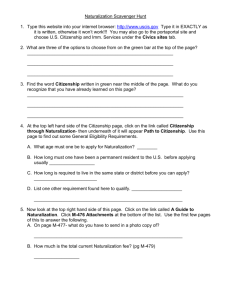

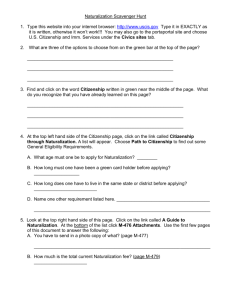

Race, Citizenship, and U.S. Law 1. Identify the following: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Naturalization Act of 1790 Naturalization Act of 1870 Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 Gentlemen’s Agreement Takao Ozawa v. United States Oriental Exclusion Act of 1924 McCarran Walter Act of 1952 Interpret the cartoon on p. 2: 1. Describe what seems to be happening in the cartoon. 2. Is the cartoon pro- or anti-nativist? What details support your answer? Article I of the U.S. Constitution states that Congress has the power “to establish a uniform rule of naturalization.” The first Naturalization Act of 1790 limited the right to become a naturalized citizen to “free white persons.” After the Civil War, the Naturalization Act of 1870 extended the right of naturalization to former slaves, making aliens of African birth and persons of African descent also eligible. Being neither white nor black, Japanese immigrants, along with other Asians, were classified as “aliens ineligible to citizenship.” Anti-Asian Measures The first immigration law to exclude a class of people targeted Asians—the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. The Asiatic Exclusion League mounted a campaign in 1905 to exclude Japanese and Koreans from the United States and the San Francisco Board of Education ruled that all Japanese and Korean students would join the Chinese at the segregated Oriental School established in 1884. (There were only 93 Japanese students in the 23 San Francisco public schools at that time, 25 were US citizens.) An amendment to the California State Political Code in 1921 established separate schools for Asian children—they attended segregated schools until the California legislature repealed the legislation in 1947. To appease those agitating for an end to Japanese immigration, President Theodore Roosevelt negotiated a "Gentlemen’s Agreement." The Japanese government agreed not to issue passports to laborers immigrating to the United States. In the case Takao Ozawa v. United States (1922), the Supreme Court ruled that Asians, being neither white nor black, were ineligible for citizenship. The majority decision stated “only free white persons shall be included [as citizens]. The intention [of Congress in its naturalization laws] was to confer the privilege of citizenship upon that class of 1 persons whom the fathers knew as white, and to deny it to all who could not be so classified…” The anti-Japanese exclusion movement climaxed with the passage of immigration legislation in 1924. The Oriental Exclusion Act of 1924 prohibited almost all immigration from Asia, even the immigration foreign-born wives and children of U.S. citizens of Chinese ancestry. Cartoon from Puck Magazine: Ending Race as an Issue in Citizenship Over the years Congress added more and more categories of people who could become citizens: Native Americans in 1924, Latin Americans in 1940, Chinese in 1943, Filipinos and Asian Indians in 1946, and—finally—Japanese and Koreans. Finally, under the McCarran Walter Act of 1952, Congress finally amended the law to read: “The right of a person to become a naturalized citizen...shall not be denied or abridged because of race…” 2