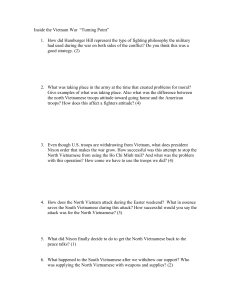

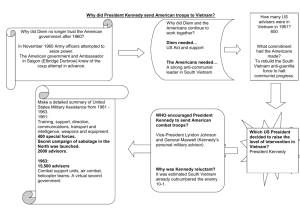

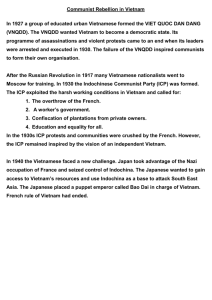

America and Vietnam Study Guide

advertisement