Paper - Lesson Study Group at Mills College

advertisement

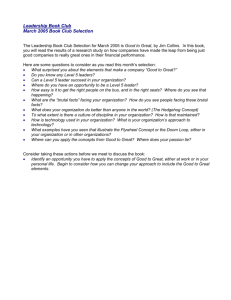

The Influence of Video Clubs on Teachers’ Thinking and Practice Elizabeth A. van Es and Miriam Gamoran Sherin Northwestern University Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association Montreal, Canada April 13, 2005 The research reported in this paper was supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant REC-0133900. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the supporting agency. DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without authors’ permission Abstract This paper examines a model of professional development called “video clubs” in which teachers watch and discuss excerpts of videos from their classrooms. In particular, this paper describes the influence of video clubs on teachers in three related contexts: (a) teachers’ comments during the video club meetings themselves, (b) teachers’ self reports concerning what they learned as result of participating in the video club, and (c) teachers’ instruction across the year. Significant changes are discussed in each context. Analysis of the video club data reveals that the teachers paid increased attention to student mathematical thinking over the course of the meetings. In addition, the teachers reported learning more about both students’ mathematical thinking and the mathematics curriculum from participating in the video club. Finally, classroom observations revealed that they attended more to students’ ideas during instruction. DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 2 Video clubs are a professional development environment in which groups of teachers watch and discuss excerpts of videos from each other’s classrooms. Typically, a facilitator helps to videotape the participating teachers’ classrooms and, with the teacher, selects a short excerpt of video to view at the next group meeting. In this way, video clubs provide teachers with a window into each other’s practices and the opportunity to discuss a variety of issues. As described in van Es (2004), a central goal of video clubs is to help teachers learn to notice and interpret significant features of classroom interactions. Because classrooms are complex environments with many things happening at once, identifying such key events is not a simple matter. This is particularly true in the context of mathematics education reform, where teachers are asked to make changes in both what and how they teach. As a result, teachers may need to learn to notice new kinds of events that take place in their classrooms and new ways to reflect on such events. In an effort to explore what and how teachers learned in this context, we examine changes in teachers’ thinking and practice in three related contexts: (a) teachers’ comments during the video club meetings themselves, (b) teachers’ self reports concerning what they learned as result of participating in the video club , and (c) teachers’ instruction across the year. We begin by summarizing the Learning to Notice Framework (van Es & Sherin, 2002). Then, we discuss the use of video as a vehicle for supporting teachers in learning to examine classroom practices in new ways, as well as, the literature on teachers changing their classroom practice. We then describe our methods for analyzing the data to examine our research questions, and then present the results of the analysis. We conclude by discussing the implications of this research on teacher cognition and professional development. DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 3 Literature Review Learning to Notice Framework Several researchers argue that a key component of teaching expertise is the ability to notice and interpret what is happening in one’s classroom (Berliner, 1994; Frederiksen, 1992; Mason, 2002). For example, Berliner (1994) suggests that expert teachers efficiently assess classroom situations, recognizing meaningful patterns in what they observe. Similarly, Rodgers (2002) and Frederiksen (1992) describe the importance of teachers being able to select those classroom interactions that they consider noteworthy and to then ascribe meaning to such events. Here, we explore what it means for teachers to identify meaningful events and interpret the meaning behind such events. As reported in van Es and Sherin (2002), we focus on three key aspects of teachers’ noticing. The first aspect of noticing involves the ability to attend to what is significant in a complex situation. Frederiksen (1992) refers to this skills as making a “call-out,” while Goodwin (1990) refers to this ability as “highlighting.” In the context of a classroom, in particular, there are a lot of things happening at one time, and the teacher must decide what deserves attention at any given moment. The second characteristic of noticing involves using knowledge of one’s context to reason about events one identifies as noteworthy. Prior research shows that as individuals become familiar with a particular type of situation, they are better able to analyze the same types of situations in the future (Lesgold et al., 1988). In the context of teaching, teachers know a lot about their students, curriculum, and school context, and they use this detailed knowledge to make sense of what they observe. DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 4 Finally, noticing involves the ability to make connections between specific events and the broader principles they represent (Copeland, Birmingham, DeMeulle, D’Emidio-Caston, & Natal, 1994; Hughes, Packard, & Pearson, 2000). When viewing a class discussion, for example, expert teachers will describe what they see in terms of principles, using phrases such as, “This is an assessment issue” or “This class is a learning community.” When teachers extrapolate from the specific to the general, they form connections between the specific instances they see and the broader pedagogical issues such events represent. Together, these three components represent some of the complexity of what is involved for teachers to make meaning of classroom interactions. Video for Teacher Learning In recent years, video and multimedia tools have been designed for professional development. Video has been used for decades to support teacher learning, and it appears to be a particularly useful tool for helping teachers learn to notice. Video is able to capture the complexity of classroom interactions, and it can be used in contexts that allow teachers time to reflect on these interactions in new ways (Sherin, 2001; Sherin & Han, 2004). In addition, video records of practice can be examined several times, with teachers adopting a different perspective each time. For example, a teacher might examine an interaction between two students, the first time attending to issues of gender and equity and the next time examining the students’ content understanding. Alternatively, a teacher might review the same interaction several times in order to gain a deeper understanding of students’ thinking. In this way, analyzing video offers teachers the opportunity to notice aspects of classroom interactions of which they may not have been initially aware, either when the event originally took place in their classroom or when viewing the video segment the first time. DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 5 More specifically, the video club environment seems particularly well suited to helping teachers learn to notice. First, prior research on teacher learning suggests that there is value in teachers coming together to examine artifacts from their own classrooms (Lewis, Perry, & Hurd, 2004; Roberts & Wilson, 1998). Classroom artifacts become common referents on which teachers can focus their discussions, which enables deep analyses of important issues related to teaching and learning. Second, teachers have few opportunities to observe their colleagues’ teaching, and video clubs provide teachers with opportunities to see images from their colleagues’ classrooms. Third, analyzing video in a group context allows multiple perspectives on the same event to be explored, and this is much less likely to happen if teachers were to analyze video segments on their own (Lampert & Ball, 1999). For these reasons, video clubs appear to show promise in supporting teachers to analyze classroom interactions in new ways. Research on Changes in Teachers’ Practice While there are many promising aspects of video clubs for supporting teacher learning, prior research reveals that it is extremely difficult for teachers to change their practice (Cohen, 1990; Cuban, 1994). This is true for several reasons. First, teachers have been apprenticed into traditional ways of teaching as they have observed teachers teaching when they were students themselves (Lortie, 1976). In addition, teachers hold beliefs that may not be in line with the vision of reform. Research has shown that changing teachers’ beliefs about teaching and learning is extremely difficult (Thompson, 1992). Further, teachers may lack the necessary knowledge and skills to teach in ways envisioned by reform (Ma, 1999). While they may believe that they are adopting reform practices, by using manipulatives or having students solve real-world problems, the core of their teaching remains unchanged because they lack the knowledge to support students as they work through new types of mathematical problems (Cohen, 1990). DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 6 While there are challenges to changing teachers’ practice, they are not insurmountable. Recent research on teacher learning and professional development show some promising ways that professional development programs can influence teachers’ practice so that they can teach in ways envisioned by reform. For example, research on Cognitively Guided Instruction (CGI) reveals that when teachers focus on understanding their students’ thinking, they can change their practice in important ways (Fennema, et al., 1996). Their classrooms became more studentcentered, with students sharing their work, explaining their thinking, and questioning one another’s ideas. In addition, these teachers focused more on students developing principled understandings of mathematics, as opposed to only procedural understandings. Another mathematics professional development program, Developing Mathematical Ideas (DMI), has also supported teachers in adopting new practices (Cohen, 2004). This program uses cases as a vehicle for helping teachers think through the major ideas of elementary mathematics and to examine how children develop those ideas. Research on this program reveals that teachers who participated in the DMI program changed in important ways. Specifically, Cohen (2004) reports that all of the teachers in her study came to believe that their students had important ideas about mathematics and that these ideas should become central to their mathematics lessons. In addition, the teachers learned important mathematics in the context of the professional development meetings, and some of them also learned mathematics through close analysis of students’ work. Finally, the teachers whose classrooms were observed came to encourage their students to articulate and represent their mathematical thinking, as well as, to promote deep investigations of students’ mathematical ideas. In other research, Borko, Davinroy, Bliem, and Cumbo (2000) report on the ways that two teachers participating in the University of Colorado Assessment Project changed their DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 7 practice. This project was designed to help teachers consider alternative methods for assessing student learning in mathematics and literacy. The authors explain that these teachers came to focus their instructional and assessment practices on students developing a conceptual understanding of mathematics, they held higher expectations for students, and the teachers shifted their roles in their classrooms, relinquishing control and acting as a facilitator of student learning. These projects point to important ways that teachers can change in their practice through long-term sustained professional development focused on teachers exploring students’ thinking about the subject matter. In this study, we seek to understand how watching video records of their own practice supported teachers to examine classroom interactions in new ways both in the context of professional development, as well as, in the context of their classroom. In addition, we explore how the teachers perceived they changed as a result of participating in video clubs. We now turn to discuss the data for this study, how we analyzed this data, and then present our findings. Data Study Design Data for this study comes from a year-long set of video club meetings attended by seven fourth and fifth grade teachers from an urban school. The teachers met once or twice a month for a total of 10 video clubs meetings. The 10 meetings shared the same format. Before each meeting, a member of the research team videotaped lessons from two of the participating teachers’ classrooms. The same researcher then viewed the tapes and identified a brief segment in which students raised interesting mathematical issues in either a whole class discussion or in a small group setting. The researcher also prepared a corresponding transcript for the teachers to DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 8 reference in the video club meeting. Clips from each teacher’s classroom were viewed two or three times throughout the year. Each meeting was videotaped and transcribed. A second data source used includes an Exit Interview with each teacher. This interview was intended to give the teachers an opportunity to share their impressions of their experience as participants in the video club. We used this interview to gain insight into the various ways the teachers believed they were influenced by participating in the video club. A third source of data for this study are classroom observations. The teachers were observed between three and nine times over the period of the video club meetings. All of the classroom observations were videotaped. Video Club Design This video club was designed with a particular goal in mind brought by the researchers in conjunction with the district administration.1 In particulary, the sessions were designed to help teachers focus on students’ mathematical thinking. For this reason, the researcher picked video excerpts in which students’ thinking was central. Furthermore, during the video club sessions, a researcher, adopting the role of facilitator, directed the teachers to examine students’ ideas about mathematics and to use evidence from the video and transcript to support their claims about the students’ understanding. Toward that end, the facilitator asked the following types of questions: “So, what method was Marisa using to solve that problem?”; “Can you tell me when that happened in the video segment?”; “What do you think that tells us about her understanding of multiplying fractions?” This design is supported by recent research on teacher learning and professional development (Ball & Cohen, 1999; Smith, 2001), as well as, by research on 1 The authors participated as both researchers and facilitators of the video club. In this way, we were participant observers (Spradley, 1980). While some may argue that participating so intimately in the research process threatens the validity of the research, we adopt Peshkin’s perspective (1988) that no research is completely objective. In fact, we believe that participating actively in the video club enabled us to understand, in an in-depth way, the range of factors that come into play as teachers examine their practice via video. DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 9 mathematics teaching and learning (Carpenter & Fennema, 1992; Schifter, 1998). Such research has shown that attending to student thinking is important for effective mathematics teaching. Analysis Qualitative methods, based primarily on fine-grained analyses of videotapes (Schoenfeld, Smith, & Arcavi, 1993), were used to examine teachers’ analyses of classroom interactions. Data analysis occurred in three phases. The first phase consisted of analyzing teachers’ comments in the video club meetings. The coding categories were initially created based on prior research (van Es & Sherin, 2002; Frederiksen et al., 1998; Hughes et al., 2000). However, the codes evolved to account for additional issues teachers raised in their analyses. Following is a description of each category. The first dimension examined whom the teachers commented on in the clip (Student, Teacher, Self, Curriculum Developers, District Administrators, or Other). The second dimension examined the topic of the teachers’ comments (Mathematical Thinking, Pedagogy, Climate, Management, or Other). Mathematical Thinking refers to mathematical ideas and understandings. Pedagogy refers to techniques and strategies for teaching the subject matter. Climate refers to the social environment of the classroom (e.g. “That was a fun lesson” or “The students seemed like they really enjoyed that lesson”), and Management refers to statements about the mechanics of the classroom (e.g. “the students aren’t exhibiting off-task behavior while working in groups” or “the teacher handled that disruption really well”). The third dimension focused on how the teachers analyzed practice (Describe, Interpret, or Evaluate). Describe refers to statements that recounted the events that occurred in the clip; Evaluate refers to statements in which the teachers commented on what was good or bad or could or should have been done differently; and Interpret refers to statements in which the teachers made inferences about what they noticed. The fourth dimension focused on the level of specificity teachers used to discuss DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 10 events they noticed (General or Specific), and finally, the fifth dimension examined whether their comments were based on the video segment they viewed or on events outside of these segments (Video or Non-Video Based). To begin, the video club transcripts were segmented into “idea units” based on when a new topic was raised for discussion in this context (Grant & Kline, 2004). This method is similar to what Jacobs and Morita (2002) describe as dividing a transcript into “idea units.” Then, each teachers’ participation within each segment was coded along the same five dimensions as had been done with the interview data. Because of the dynamic nature of conversations in the video club meetings, each teacher may have participated differently within a given segment. In order to characterize how the individual teachers analyzed video, however, each teacher received one code per dimension for each segment based on his or her primary focus. This primary focus was determined by looking at the context in which his or her comments were made. Prior research suggests that this is a valid method. Research on quantifying analysis of verbal data (Chi, 1997) highlights the value of conceptualizing chunks at different grain sizes, while research on discourse analysis points to the importance of considering the broader context of the conversation in which individual utterances are made (Goffman, 1981; Hymes, 1974). One researcher coded all 10 of the video club meetings in this way, while a second researcher coded five of the ten meetings.2 Inter-rater reliability was initially 88%. Any differences between the two coders were discussed and resolved through consensus. Once all of the segments were coded, percentages were calculated for each category within the five dimensions. This was done for each teacher, for each meeting. Based on this analysis, a table was created indicating these percentages. 2 The five meetings that were double coded were randomly selected but represented meetings from the beginning, middle, and end of the series of meetings. DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 11 To examine whether the teachers changed in how they talked about video from the beginning to the end of the series of meetings, the percentages for each dimension, per teacher, for the second meeting in which the teachers were present3 and for the final video club meeting were compared. This allowed examination of whether the teachers talked about classroom interactions differently at the beginning of the series of meetings compared to the end of the series of meetings. Statistical methods were also used to test the significance of any changes in teachers’ analyses from the early to the late video club meetings. Specifically, a z-test for dependent samples was conducted to examine the significance of the differences in the percentages of comments the teachers made in the areas of Student, Mathematical Thinking, Interpret, Specific, and Video-Based, from the early to the late meetings. Given that our research hypothesis is that the percentages from the late meeting will be greater than the percentages from the early meeting in these areas, we used a one-tailed z test. As before, z values greater than 1.645 indicate statistically significant differences in comments between early and late meetings. The second phase explored the areas in which the teachers reported learning from participating in the video club. To do this, we conducted what we call an Exit Interview with each teacher individually. In this interview, we asked the teachers to comment on what they thought were the most and least valuable aspects of the video club. Then, we asked the teachers how participating in the video club influenced their knowledge of students, of mathematics, of curriculum, and of mathematics teaching. Finally, we asked the teachers to describe how their instructional practices had changed, if at all, as a result of participating in the video club. 3 The first video club meeting was not used because the discussion focused on introductory and management issues so it was not representative of the kind of discussion that took place in the other video club meetings. DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 12 All of the interviews were transcribed. Then, two researchers created summaries of each individual teachers’ comments for each question. The researchers then compared their summaries to make sure there was consistency within the two sets of summaries. Then, we looked across the summaries for common themes among the individual teachers’ responses. Two themes emerged from the data: Learning about Curriculum and Learning about Student Thinking. The data were reexamined looking for confirming and disconfirming evidence related to each theme. Finally, the third phase of analysis involved studying the extent to which teachers’ classroom practices were influenced by their participation in the video club. Classroom observation data was used to investigate changes in practice. Four of the seven teachers were observed once early in the year and once late in the year. The three other teachers were observed three times early in the year and three times late in the year. When examining the data, we focused on whole class or small group discussions because we thought these would be places where we could see the extent to which teachers focused on students’ ideas (Hufferd-Ackles, Fuson, & Sherin, 2004). Two researchers reviewed each video tape from the classroom observations and created analytic memos concerning how students ideas were solicited by the teachers, the nature of the questions teachers asked the class, and how the teachers responded to students’ comments and students’ confusions (Franke, Carpenter, Levi, & Fennema, 2001). The memos were then used to identify common themes across the seven teachers. This resulted in identifying three themes: Making Space for Student Thinking, Teacher Questioning, and Learning while Teaching. The videos were then reviewed again looking for confirming and disconfirming evidence related to each theme. DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 13 Next, we turn to discuss the results of the data analysis. First, we will share the results of the analysis of the nature of the teachers’ comments in the video club meetings. Then, we will discuss how the teachers perceive they changed as a result of participating in the video club. Finally, we will turn to discuss the findings related to teachers’ classroom practice. Results & Discussion Changes in Video Club Context To begin, analysis of the teachers’ comments in an early and late video club meeting reveal that the teachers began to talk about the video excerpts in different ways by the end of the series of meetings (see Table 1).4 Specifically, the teachers increased in the percentage of comments they made about the students and mathematical thinking. Further, rather than evaluating what took place in the video, the teachers came to more frequently interpret the events viewed in the video. In addition, the teachers came to discuss specific events rather than to comment more generally on what they noticed. Finally, their comments became more grounded in the events in the video segments they viewed in the meetings. For a more detailed summary of the individual teachers’ analyses in the early and late video club meetings, see Appendix A. 4 One teacher, Drew, a first-year teacher, was eliminated from this analysis because he made only two comments in the second meeting he attended and one comment in the final meeting. With so few comments, it was difficult to determine the nature of his noticing in this context. DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 14 Table 1 Teachers’ Overall Analytic Focus in Second and Final Video Club Meetings Teachers Attended Agent Topic Stance Specificity Video focus Total Student Teacher Curriculum Developers Self Other Math Thinking Pedagogy Climate Management Describe Evaluate Interpret General Specific Video-based Non video-based Early Meeting Late Meeting (36) 44% (53) 70% (14) 17% (5) 6% (12) 15% (9) 12% (16) 20% (9) 12% (3) 4% (0) 0% (41) 51% (57) 75% (30) 37% (15) 20% (7) 8% (4) 5% (3) 4% (0) 0% (26) 32% (17) 22% (34) 42% (12) 16% (21) 26% (47) 62% (31) 38% (13) 17% (50) 62% (63) 83% (26) 32% (52) 68% (55) 68% (24) 32% (81) 100% (76) 100% Note. Values in parentheses indicate the number of comments made in a particular category. The percentages follow. Using the z test to examine differences in the percentages of comments made by dependent samples reveals that in all five areas in which we hypothesized there would be an increase, there was a statistically significant difference at the .05 level. In particular, the onetailed z test statistic for the difference between the teachers’ comments in the early and late meetings on Student was 3.17; on Mathematical Thinking; the one-tailed z test statistic was 3.0; on Interpret was 6.0; on Specificity was 2.3; and on Video-Based was 5.6. Thus, in the video club context, the teachers came to analyze video in new ways over time, analyzing students’ mathematical thinking in detailed ways based on the events in the video clips. DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 15 Teachers’ Self-Reports of Changes In addition to observing changes in the ways teachers talked about classroom interactions in the video club meetings, we also wanted to examine whether the ways in which teachers perceived teaching and learning outside of the video club had been influenced. Based on our analysis of the Exit Interviews, the teachers reported that participating in the video club helped them learn about important aspects of their practice. Specifically, they claimed to have learned about the curriculum and about students’ mathematical thinking. All seven of the teachers reported that they learned about the mathematics curriculum from having opportunities to view lessons from other teachers’ classrooms and other grade levels. The teachers were in their third year of using a reform-based curriculum, and many had concerns about not being familiar enough with these materials. Therefore, they viewed learning about the curriculum as a significant achievement. For example, when asked what he thought was the most valuable part of the video club, one fourth grade teacher, Daniel responded: “Just seeing… oh, [the fifth graders are] doing fractions there too! Not that I didn’t know that before, but just to be able to see that and how it’s going on and hear the teachers talking about what their expectations are, what [the students] need to know and how they go about teaching their math. And just maybe [seeing] oh, they use this key word, or this phrase, or this vocabulary… this stuff is important in fifth grade. If I see it there, I can kind of bring that in. We just don’t have enough time in the day to talk about these things. I should know at least all the chapter titles and all the concepts they do in fifth grade, but you know nobody gives you any time to do that so a lot times you just don’t know the stuff that you should know. So, that was kind of valuable.” Being provided the time and space to view lessons from other teachers’ classrooms was a common sentiment across all teachers. Another teacher, Frances commented, “Especially, for me, having taught third [grade] and gone to fifth, it was interesting to see how what I taught in DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 16 third grade really related to fourth and what they’re teaching at fourth, how that has helped me in fifth. So, seeing that continuity really helps.” To be clear, the video club did not have as a central purpose supporting teachers in making curricular connections. However, viewing video of one another’s teaching helped them accomplish this important goal. In addition, the teachers reported learning more about students’ mathematical thinking and the value of attending to students’ ideas during instruction. One teacher, Yvette, commented, “The video [club meetings] allowed me to kind of think about math and look at why [the students] are understanding or why they’re not.” Frances also reported that the video club meetings helped her learn to attend to students’ ideas. When asked if she thought participating in the video club influenced the way she saw her classroom during instruction, she replied: “Yes, definitely because you caught all those kids 'cause you saw them right there on video, and the way you [asked] ‘now, what do you think she meant by that?’ I don't think, as teachers, we have the opportunity to do that very often because it's so fleeting. A child gives an answer and you've got to go on to the next [problem], and then you watch the clock. So, it really focused on the kids. If you understood what she was saying, you could really understand if she got this or not because you think she didn't get it because she didn't spit it out the way you wanted her too, she didn't use the terminology, or she didn't get the right answer. But, if you really stop and think, ‘yeah, she did get it...she was just saying it a different way or she got part of it.’ So, the Video Club really does help…you slow down and really listen to kids.” These excerpts illustrate the ways that the teachers believed that the video club helped them learn to listen to their students while teaching. Again, this is an important goal of the mathematics reform movement, as teachers are expected to listen closely to the ideas their students raise and use their ideas to inform pedagogical decisions (Arvold, Turner, & Cooney, 1996; National Council of Teachers of Mathematics [NCTM], 2000). In particular, six of the seven teachers claimed that the video club influenced the way they think about their students and their students’ thinking about the mathematics. One teacher, DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 17 Wanda, however, did not believe she was influenced in these ways. When asked if she thought participating in the video club influenced how she thought about her students, she replied, “Um, I think I’m fairly strong at thinking about why a student is coming up with an answer that they’re coming up with.” Interestingly, analysis of her classroom instruction (discussed in the next section) revealed that, in her practice, she did pay more attention to students’ mathematical thinking over time. Further, of the six teachers, all commented that not only did they learn about students’ thinking from the video club, but they also changed their instruction in order to pay attention to students’ ideas in that context. For instance, Drew, a first-year teacher, said, “I notice different things that they don’t understand and I have them talk through it.” He goes on to explain that he uses the information students provide him about their mathematical understanding and will teach a different way if they are having difficulty. Another teacher, Linda, said that she found that later in the year, she slowed down her instruction and held herself back from giving the students the answer. In addition, she also believes that she provided them with the opportunities to work through the problems on their own. And Elena remarked that she often asked her students to explain their thinking more later in the year and that she would then think about different ways to have them approach their learning based on what she came to know about their mathematical understanding from their explanations. Changes in Teachers’ Instruction Thus far, we have identified changes in the ways teachers’ commented on instruction in the video club context. In addition, we reported the ways the teachers perceived their understandings and practices changed as a result of participating in the video club. Another DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 18 important question to consider is the extent to which their participation in the video club meetings may have influenced their classroom practice. We now turn to address this issue. In examining the teachers’ classroom instruction, we found that all seven teachers changed in ways that suggest they were noticing new types of classroom interactions and attending to them in new ways. In particular, the teachers made space for students’ thinking to become public in the classroom, they changed the nature of their questioning, and they learned in the context of teaching. First, the teachers appeared to make space for students’ thinking to emerge in the classroom. In particular, they came to recognize and value students’ ideas more over time, paying attention to unsolicited questions and comments from their students. For instance, in the classroom observations that took place at the end of the year, teachers would often notice when students had their hands raised and would call on them to share their thoughts. In contrast, early in the year, the teachers would only call on students to respond to questions they posed to the class. In addition to noticing that students had ideas to contribute, they also spent more time on mathematical problems late in the year. An important question to consider is how this additional time on the problems was being used. Analysis of the classroom observations reveals that they were providing time for several students to share their thinking and to comment on one another’s work. Often, the teachers would invite multiple students to share their solution strategies to a mathematical problem or they would call on several students to comment on the same problem. When analyzing the teachers’ practice early in the year, it was not common practice for the teachers to call on several students to engage in discussions about a mathematical problem. Thus, it is not a matter of the teachers only taking more time to solve problems, but how the time was spent was qualitatively different than how it was spent earlier in the year. DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 19 Second, the teachers changed over time in terms of their questioning. In particular, the teachers followed up on students’ responses, asking probing questions about their strategies for solving problems and their underlying thinking for using a particular approach. For example, later in the year, the teachers asked questions like, “Maria, I’m not sure I follow you. Why did you put the decimal point in that spot?” or “Are you thinking about this in terms of hundreds?” We claim these teachers’ questions became more open-ended in nature. In other words, they were questions to which the teachers did not have an answer in mind when they asked them and about which they were wanting to understand more. This shift is significant because these types of questions are ones that engage students in deep mathematical thinking. Further, they show to the students that their ideas are valued and worth exploring and that they can contribute to the ways that mathematics is learned and understood. And finally, the data reveals that in the context of their classrooms, the teachers were learning while teaching. Specifically, at times they adopted a stance of learner, appearing unclear or confused about an idea that a student raised and wanting to make sense of what had been said. For instance, later in the year, several teachers made comments like, “Hmmm… I’m a little confused. Let me think about this” or “I hadn’t thought of that before.” These types of comments suggest that the teachers were not always certain about an idea a student raised and that they were positioning themselves as learners in the classroom. Interestingly, one teacher did show behaviors early in the year that suggests he was learning while teaching. This teacher, Drew, was in his first year of teaching, which explains why he may have been more uncertain about students’ comments. As a first year teacher, he did not yet have a knowledge-base of the kind of comments students typically make, thus he was often in a position to be learning while teaching. DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 20 Overall, across these categories, four of the seven teachers made dramatic shifts in their practice over all three themes, while two other teachers showed more modest gains. Two teachers, Wanda and Yvette, had begun to incorporate these practices late in the year, but it was not consistent and disconfirming evidence was noted late in the year. And the other teacher, Elena, exhibited practices in line with the first two themes early in the year, so while we saw an increase by the end of the year, it was not as dramatic as for the other teachers. These findings suggest that the teachers did begin to change their practice in some important ways. Future research is needed to understand these changes more deeply, specifically, conducting more classroom observations to examine if these changes occur on a regular basis. Further, additional research is needed to study teachers who are not a part of a video club to examine if they change in similar ways over the course of the school year. While the data are limited, these findings do reveal some important ways that teachers’ classroom practice reflected the kind of thinking in which the teachers were engaged in the video club meetings, as well as, the kind of practices called for by mathematics reform. Specifically, the teachers began to notice when students had ideas to contribute, and they provided space for those ideas to become shared. In addition, the teachers probed students to understand their thinking, rather than to point them in a direction for solving problems. And finally, the teachers revealed their own confusions to the class and allowed themselves to learn while they were teaching. These techniques were not discussed explicitly in the video club. Yet, we claim that they are directly related to teachers’ increased attention to student thinking during the video club meetings. Discussion & Conclusion In the video club described herein, we see that the teachers learned to talk about classroom interactions in new ways over time. Specifically, they learned to focus on students’ DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 21 mathematical thinking in their analyses of the video segments in the video club context. This is not a minor accomplishment. Prior research reveals that professional development does not often effect teachers’ thinking and practices (Cohen, 1990). But here, we see teachers engaging in the kind of thinking advocated by mathematics reform. We also see that the teachers perceived the video club as a valuable form of professional development. They reported learning about curriculum issues, which was particularly important for this group of teachers, as the curriculum design required several of the teachers to teach in new ways. In addition, the teachers came to understand how what they do in their individual classrooms influences teaching and learning at other levels. It appears that discussing these curriculum issues in the video club meetings provided a space for these teachers to build a teacher learning community. This is significant as research on teacher learning reveals the importance of teachers meeting on a regular basis to discuss substantive, challenging issues related to their practice (Thomas, Wineburg, Grossman, Myhre, & Woolworth, 1998). In addition, the teachers also reported learning about student thinking. In particular, they said that they learned about different students’ ideas, and they claim they learned the value of attending to students’ thinking during instruction. In addition, the teachers said that they changed their pedagogical strategies in order to pay attention to students’ ideas in that context. Analysis of the classroom observation data reveals that the teachers did change in ways they perceived. In particular, the teachers provided space for students’ ideas to emerge, they probed students’ thinking, focusing on students’ ideas, and they adopted a stance of learner in the context of their classroom. These are all important goals of mathematics reform (NCTM, 2000). In summary, the results reported herein suggest that video clubs are an effective environment for supporting changes in teachers’ practice, specifically, supporting them in DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 22 learning to focus on students’ mathematical thinking during instruction. We saw in this study that the teachers developed strategies for examining student thinking, as the facilitators modeled particular types of questions to ask in order to understand students’ ideas. In addition, the teachers appear to have learned strategies for analyzing student reasoning and understanding, and the data suggests that they used these methods while teaching as well. While the results of this study are encouraging, clearly, additional work is needed. This analysis reports on one video club with seven teachers. We recognize that we can not generalize from this data set to other video club settings or other video-based professional development. An important question to pursue is whether or not all teachers change in these ways in their instruction across the school year. Future research will examine if teachers are likely to pay more attention to student thinking over time, whether or not they participate in a video club. Finally, future research will explore how the design of this particular video club influenced teachers’ learning to notice in the video club setting. The results of this research will inform the design of video-based professional development that is both productive and meaningful for teachers. DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 23 References Arvold, B., Turner, P., & Cooney, T.J. (1996). Analysing teaching and learning: the art of listening. The Mathematics Teacher, 89, 326-329. Ball, D. L., & Cohen, D. K. (1999). Developing practice, developing practitioners: Toward a practice-based theory of professional education. In G. Sykes and L. Darling-Hammond (Eds.), Teaching as the learning profession: Handbook of policy and practice (pp. 3-32). San Francisco: Jossey Bass. Berliner, D. C. (1994). Expertise: The wonder of exemplary performances. In J.M. Mangier & C. C. Block (Eds.), Creating powerful thinking in teachers and students: Diverse perspectives (pp. 161-186). Fort Worth, TX: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston. Borko, H., Davinroy, K.H., Bliem, C.L., & Cumbo, K.B. (2000). Exploring and supporting teacher change: Two third-grade teachers’ experiences in a mathematics and literacy staff development project. The Elementary School Journal, 100(4), 273-306. Carpenter, T., and Fennema, E. (1992). Cognitively guided instruction: Building on the knowledge of students and teachers. International Journal of Educational Research, 17, 457470. Chi, M.T.H. (1997). Quantifying qualitative analyses of verbal data: A practical guide. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 6(3), 271-315. Cohen, D. K. (1990). A revolution in one classroom: The case of Mrs. Oublier. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. 12(3), 327-345. Cohen, S. (2004). Teachers’ professional development and the elementary mathematics classroom: Bringing understandings to light. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 24 Copeland W.D., Birmingham, C., DeMeulle, L., D’Emidio-Caston, M., & Natal D. (1994). Making meaning in classrooms: An investigation of cognitive processes in aspiring teachers, experienced teachers, and their peers. American Educational Research Journal, 31(1), 166196. Cuban, L. (1990). Reforming Again, Again, and Again. Educational Researcher (19)1, 3-13. Fennema, E., Carpenter, T.P., Franke, M.L., Levi, L., Jacobs, V.R., and Empson, S.B. (1996). A longitudinal study of learning to use children’s thinking in mathematics instruction. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 27(4), 403-434. Franke, M.L, Carpenter, T.P., Levi, L., and Fennema, E. (2001). Capturing teachers’ generative change: A follow-up study of professional development in mathematics. American Educational Research Journal, 38(3), 653-689. Frederiksen, J. R. (1992). Learning to “see”: Scoring video portfolios or “beyond the huntergatherer in performance assessment. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco. Goffman, E. (1981). Forms of talk. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Goodwin, C. (1994). Professional vision. American Anthropologist, 96, 606-633. Grant, T. & Kline, K. (2004). The impact of long-term professional development on teachers’ beliefs and practice. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Diego. Hufferd-Ackles, K., Fuson, K. C., and Sherin, M. G. (2004). Describing levels and components of a Math-Talk Learning Community. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 35(2), 81-116. DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 25 Hughes, J. E., Packard, B. W., & Pearson, P. D. (2000). The role of hypermedia cases on preservice teachers’ views of reading instruction. Action in Teacher Education, 22(2A), 24-38. Hymes, D. (1974). Foundations in sociolinguistics: An ethnographic approach. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Jacobs, J.K. & Morita, E. (2002). Japanese and American teachers’ evaluations of videotaped mathematics lessons. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 33(3), 154-175. Lampert, M., & Ball, D. L. (1998). Mathematics, teaching, and multimedia: Investigations of real practice. New York: Teachers College Press. Lesgold, A., Rubinson, H., Feltovitch, P., Glaser, R., Klopfer, D., & Wang, Y. (1988). Expertise in a complex skill: Diagnosing x-ray pictures. In M.T.H. Chi, R. Glaser, & M. Farr (Eds.) The nature of expertise (pp. 311-342). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Lewis, C., Perry, R., & Hurd, J. (2004). A deeper look at lesson study. Educational Leadership, 18-22. Lortie, D. (1976). School Teacher: A Sociological Study. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Ma, L. (1999). Knowing and teaching elementary mathematics. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Mason, J. (2002). Researching Your own Practice: The Discipline of Noticing. London: RoutledgeFalmer. National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. (2000). Principles and standards for school mathematics. Reston, VA. Roberts, L. & Wilson, M. (1998, February). An integrated assessment system as a medium for teacher change and the organizational factors that mediate science teachers' professional development. BEAR Report Series, SA-98-2,University of California, Berkeley. DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 26 Rodgers, C.R. (2002) Seeing student learning: Teacher change and the role of reflection. [Electronic version]. Harvard Educational Review, 72(2). 230-253. Retrieved August 8, 2003, from http://www.edreview.org/harvard02/2002/su02/s02ordg.htm. Schifter, D. (1998). Learning mathematics for teaching: From a teachers’ seminar to the classroom. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 1(1), 55-87. Sherin, M. G. (2000). Viewing teaching on videotape. Educational Leadership, 57(8), 36-38. Sherin, M. G., & Han, S. (2004). Teacher learning in the context of a video club. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20,163-183. Smith, M.S. (2001). Practice-based professional development for teachers of mathematics. Mathematics teaching in the middle school, 7(8), 474-475. Reston, VA: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. Spradley, James P. (1980). Participant observation. Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers. Thomas, G., Wineburg, S., Grossman, P., Oddmund, M., & Woolworth, S. (1998). In the company of colleagues: An interim report on the development of a community of teacher learners. Teaching and Teacher Education, 14(1), 21-32. Thompson, A. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and conceptions: A synthesis of the research. In D. Grouws (Ed.), Handbook of research in mathematics teaching and learning. (pp. 127-146) New York: MacMillan. van Es, E.A. (2004). Learning to notice: The development of professional vision for reform pedagogy. Unpublished dissertation. Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois. van Es, E. A., & Sherin, M. G. (2002). Learning to notice: Scaffolding new teachers' interpretations of classroom interactions. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 10 (4), 571-596. DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 27 Appendix A - Individual Video Club Teachers’ Comments in the Early and Late Video Club Meetings Teacher Linda Elena Wanda Daniel Frances Yvette Agent Student Teacher Self Curriculum Developers Other Student Teacher Self Curriculum Developers Other Student Teacher Self Curriculum Developers Other Student Teacher Self Curriculum Developers Other Student Teacher Self Curriculum Developers Other Student Teacher Self Curriculum Developers Other Early Meeting (4) 45% (5) 55% (0) 0% (0) 0% (0) 0% (4) 80% (0) 0% (1) 20% (0) 0% (0) 0% (6) 33% (5) 28% (5) 28% (2) 11% (0) 0% (7) 44% (1) 6% (5) 31% (3) 19% (0) 0% (9) 47% (0) 0% (5) 26% (4) 21% (1) 6% (6) 43% (3) 22% (0) 0% (3) 21% (2) 14% Late Meeting (7) 70% (0) 0% (1) 10% (2) 20% (0) 0% (5) 83% (1) 17% (0) 0% (0) 0% (0) 0% (11) 69% (1) 6% (2) 12% (2) 12% (0) 0% (9) 64% (2) 14% (2) 14% (1) 8% (0) 0% (12) 74% (0) 0% (2) 12.5% (2) 12.5% (0) 0% (9) 64% (1) 8% (2) 14% (2) 14% (0) 0% Topic Late Meeting (9) 90% (1) 10% (0) 0% (0) 0% Stance Math Thinking Pedagogy Climate Management Early Meeting (4) 44% (3) 33% (2) 22% (0) 0% Describe Evaluate Interpret Early Meeting (1) 11% (5) 56% (3) 33% Late Specificity Meeting (3) 30% General (1) 10% Specific (6) 60% Early Meeting (4) 45% (5) 55% Late Video Focus Meeting (1) 10% Video-based (9) 90% Non video-based Early Meeting (5) 55% (4) 45% Late Meeting (7) 70% (3) 30% Math Thinking Pedagogy Climate Management (3) 60% (1) 20% (1) 20% (0) 0% (5) 83% (1) 17% (0) 0% (0) 0% Describe Evaluate Interpret (2) 40% (1) 20% (2) 40% (1) 17% (1) 17% (4) 66% General Specific (2) 40% (3) 60% (0) 0% Video-based (6) 100% Non video-based (3) 60% (2) 40% (5) 83% (1) 17% Math Thinking Pedagogy Climate Management (9) 50% (8) 44% (0) 0% (1) 6% (11) 69% (3) 19% (2) 12% (0) 0% Describe Evaluate Interpret (7) 39% (7) 39% (4) 22% (4) 25% General (2) 12% Specific (10) 63% (7) 39% (11) 61% (3) 19% Video-based (13) 81% Non video-based (5) 28% (13) 72% (11) 69% (5) 31% Math Thinking Pedagogy Climate Management (7) 44% (7) 44% (1) 6% (1) 6% (10) 71% (4) 29% (0) 0% (0) 0% Describe Evaluate Interpret (8) 53% (5) 29% (3) 18% (1) 7% (4) 29% (9) 64% General Specific (8) 50% (8) 50% (5) 36% (9) 64% (5) 35% (11) 65% (9) 64% (5) 36% Math Thinking Pedagogy Climate Management (12) 63% (5) 26% (2) 11% (0) 0% (13) 81% (2) 13% (1) 6% (0) 0% Describe Evaluate Interpret (5) 26% (7) 37% (7) 37% (4) 25% General (2) 13% Specific (10) 63% (3) 16% (16) 84% (2) 13% Video-based (14) 87% Non video-based Math Thinking Pedagogy Climate Management (6) 43% (6) 43% (1) 7% (1) 7% (9) 64% (4) 28% (1) 8% (0) 0% Describe Evaluate Interpret (3) 21% (9) 65% (2) 14% (4) 29% (2) 14% (8) 57% (7) 50% (7) 50% (2) 14% Video-based (12) 86% Not video-based General Specific Video-based Non video-based (6) 32% (13) 68% (2) 14% (12) 86% (9) 56% (7) 44% (11) 79% (3) 21% Note. Values in parenthesis indicate the number of comments made in a particular category. The percentages follow. DRAFT – Do not distribute or cite without author’s permission 28