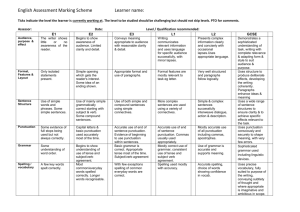

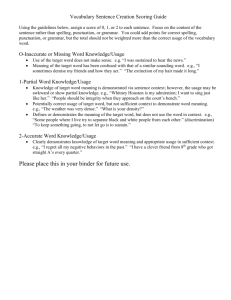

The effective use of English

advertisement