File

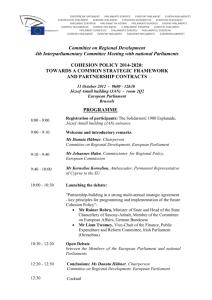

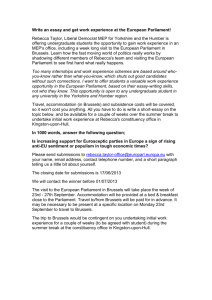

advertisement