OEE in the office

advertisement

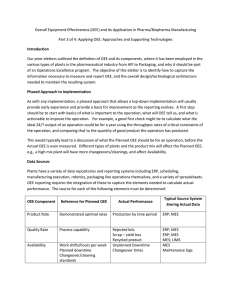

OEE in the office The measurement of Over All Equipment Effectiveness (OEE) has been an established tool used in manufacturing for many years. But can it be applied in nonproduction areas, and particularly in the office environment? The answer is yes, if the topic is treated sensitively. Measuring available time, output and quality are equally applicable to many office activities, and some interesting insights can be obtained by looking at a similar composite measure for these areas. However one should be careful not to take the analogy too far, as one cannot increase employee ‘uptime’ with a spanner! What is OEE and why is it so widely used in manufacturing? In manufacturing environments it was long held that there has to be a trade off between quality and output. Production would scream at engineering that they wanted more “up time”, while engineering complained to production that there was never enough time to do proper maintenance. When quality issues arose production would blame poor maintenance who in turn would introduce additional maintenance checks which reduced up-time and hence productivity. This jaundiced view was in part due to the absence of a single measure that aligned engineering and production objectives. The virtue of OEE is the way it achieves this, by dealing with 3 critical factors, each of which has the ability to adversely impact on customer service and cost. For those unfamiliar with the measure, it is defined as: OEE= Availability x Performance rate x Quality rate A definition of each of these elements is given in table 1. However one can easily see how this measure recognises the trade off between maintenance time, output and quality. A search of the literature quickly reveals two hot topics around OEE. The first is a fundamental objection to OEE as a measure. Those who object to its use generally complain that, due to its aggregate nature, it fails to assist diagnosis of the underlying problem. Proponents however defend its use as, in one number, it is possible to measure improvement in performance of a production line, taking a balanced view across utilisation, efficiency and quality. The second topic of conversation is around ‘what constitutes available time’ for a piece of equipment when calculating utilisation. Hard-liners argue that every available hour in the year should be considered, as only when a machine runs 24hrs, 365 days per year is it being ‘fully utilised’. Others argue that it should only be the hours which are ‘scheduled’ as the former calculation would result in a very low number for a plant only working 8 hr shifts. It is not my intention to address these issues in depth. Reference to them is purely to set the context in which OEE is currently used in manufacturing, before moving on to the question of applicability in non-production environments. Having said this, my opinion based on 20 years of operations management is that all the arguments have merit, depending on what the purpose of the measure is. From a senior management point of view, they want one number that identifies how much opportunity there is to release under utilised capacity in the supply chain. They have the ability to rationalise manufacturing capacity and change shift patterns such that the assets are more highly utilised. They are not bothered about whether it is poor quality or poor uptime that is the root cause, they just know they have an opportunity. In this instance, a more appropriate measure may be Total Effectiveness Equipment Performance (TEEP)1 Conversely, a production supervisor has no ability to impact on the loading of the plant (they must meet demand at the pull of the customer) but they very much want to know what is hammering their OEE; is it poor quality or poor up time? So as usual it isn’t a case of one size fits all. Measures should be ‘fit for purpose’. Unfortunately this may result in a disconnect between plant and supply chain measures. It should be noted that the calculation is however the same, all that differs is the figure used for “available time”. What about office environments? Let us now think about a typical office environment and, more specifically, an office process. For the sake of comparison, consider an office responsible for some transactional process such as invoice processing. One can search the office environment for equipment that is used for this process and apply the OEE principles. e.g. the Fax machine, the photocopier, the computer, the calculator or the stapler. Very soon however one will realise that the rate limiting step, the highest cost element and the biggest threat to quality is not the equipment, but the staff carrying out the processing. So what can be learnt from the OEE approach? A simple comparison of what is driving effectiveness in the two scenarios highlights the similarities and differences. Table 1 Equipment Employees Availability Run time Scheduled run time Hours at workstation Planned hours at workstation Performance rate Output per unit time Name-plate rate Output per unit time Theoretical or standard rate Right first time Total output Right first time Total output Quality rate It is evident that the approach adapted to Overall Employee Effectiveness has the same merits as with equipment effectiveness. If one can optimise the time the 1 Overall Equipment Effectiveness- Robert C. Hansen; Industrial Press, 2001 employee is working, the rate they work at, and the first time quality, this will drive effectiveness and hence profitability. What’s new? I suspect that some readers are considering moving on now, the above factors have long been considered by employers as key drivers of profitability and they have measures in place. If this is the case, let me ask some questions: Why, when you call a call centre do you get treated brusquely? (or worse still have the phone picked up and then immediately put down again?) Why do legal documents take so long to be drawn up and at such expense? Why is temporary labour used so much in transaction centres? I believe the answer lies in the independent way in which employers use a variety of measures to drive performance in these environments. If a composite measure were used, incorporating the factors shown above, it would be easier to optimise business performance. In the examples above it is clear that some call centres focus on the number of calls processed at the expense of quality. Similarly, most legal practices I have come across focus very heavily on quality (after all they will be liable for contract errors) but pay little attention to ‘standard’ procedures or indeed hours of business! Transaction centres accept a high degree of absenteeism due to their focus on output and correctness of transactions. Measurement systems How can one measure these different elements? At first glance it might seem that absentee figures should give the first number. However the fact that they have clocked in does not necessarily mean they are ‘on station’. Typical absenteeism figures in the UK are about 3.5%. (Present at work 96.5%) However, making allowance for paid breaks, coffee and comfort breaks, a good figure for being present at workstation in clerical roles is probably nearer 80%. (Verification of this number for your business will require a method of sampling or recording.) Output to standard should be easier, but only when demand is saturated, constant or levelled. Office processes (particularly service processes) are usually driven by customer demand with little scope to build inventory at the end of the process. But how do you set the standard? With a machine it is typical to use either the name-plate capacity or the ‘best sustained’ output rate. In an office environment it may be necessary to calculate an average over several employees and over some time. Quality measures are also different in an office environment. The reason for this is that usually you are dealing with quality parameters that should be measurable by the employee. (Accuracy of numbers, spelling mistakes, correct addresses etc.) so typically there is no independent check step. In manufacturing environments the parameters often need specialist equipment or skills to determine them so there is more likely to be an independent check step. (Although this is changing as operators are given more responsibility for quality and checking equipment becomes easier to use.) For this reason, business process defects are often only identified at the input to the next part of the process (or by the customer!). Measurement of the defect rate therefore requires tracability back to the employee, and there may be a significant lag in the measurement. Example of use of a composite measure Assuming you can obtain some realistic measures, you should be able to construct a table like this: Employee A Employee B Employee C Employee D Department X % time at work station 80% 75% 78% 75% 80% Output to standard 90% 95% 95% 89% 99% Right first time OEE 99% 97% 93% 90% 99% 71% 69% 69% 60% 78% Looking at the different measures in this way leads one to some observations. The composite measures for each employee (A to C) are very similar, but what are the impacts on the business. Employee A has good attendance at work station level of 80%, a poor output to standard of 90% but an excellent (relative) quality performance of 99%. This lack of productivity may lead to additional overtime costs, but will not cause large amounts of rework or the need for temporary staff to compensate for excess absence. Employee B has a poorer presence level at 75%, achieves 95% of standard output rate but a poor quality rate at only 97%. This type of employee is likely to need support from temporaries due to absence, and is also likely to lead to re-work due to poor quality. Employee C has very poor quality performance leading to large amounts of rework and probably lack of customer satisfaction. Employee D is a temporary employee. The poor output and quality performance are products of the system, not the individual. Inexperienced staff either need to go up a learning curve to protect quality, probably meaning some sort of ‘buddy’ system which impacts productivity, or are thrown in the deep end which has an impact on quality. It should be noted that this learning curve is true of any new employee and is part of the ‘life cycle curve’ for an employee, just as one would expect lower efficiencies from a new piece of equipment. The measure can also be used at the departmental level. Achieving a departmental level of nearly 80% would be considered very good. (Department X.) Problems and opportunities It is arguable that this analytical approach reduces people to the level of machines, and that is certainly one interpretation. However I would argue the contrary, that it recognises the differences in employees and how they may achieve high levels of effectiveness, through combinations of attendance, speed, and diligence. It has been said that ‘Nothing de-motivates like inequitable measures”. This composite measure allows for the different strengths and preferences of employees, while allowing them all to strive for the benefit of the business. Having said this, there are some practical problems to be overcome. Measuring time at the workstation requires a definition of the “workstation”. In some cases employees will be unable to fulfil their duties unless they are at a computer screen or desk. However few jobs require such a narrow view of value added work. People in transactional roles can also be adding value when they are sharing knowledge with other employees, seeking advice from a supervisor or retrieving files from a store. A practical approach has to be taken to this measurement, and recognition given to the value of these other activities. It should also be noted that current health legislation dictates that employees working at display screens must be allowed regular breaks. Other problems arise around setting standards. Few office environments have absolutely identical repeating activities. Telephone queries have a variable duration, and invoice clearance varies in complexity. There are some statistical techniques already widely used in areas such as call centres that help address this variation, based on queuing theory. As mentioned previously, some averaging will be required when aiming to set standards. It should also be recognised that use of the ‘current best achieved’ as a standard is in it’s self a limiting assumption. Elimination or simplification of process steps can have a marked impact on the time required. (To address this opportunity area, more in depth analysis using lean tools, such as value added analysis, is required.) Application of this approach identifies several improvement opportunities. But each of these areas generates further questions. Absenteeism questions: What keeps your staff away from the workstation? Would provision of local refreshment areas and washrooms increase the contact time? Is the environment conducive to their work? What other activities are they doing that are value added? Are they absent due to work related issues such as RSI?2 Output questions: Does the department employ standard work? What are the best rates being achieved? Can cross skilling or upskilling be implemented? Can any tasks be eliminated or automated? What are the detailed activities that take up the time and cause variation? Quality questions: Which tasks have the highest re-work rates? What are the common factors that constitute the root causes? Can any elements be ‘error proofed’? Are errors time based? (Certain times of day or certain shifts?) 2 Repetitive strain injury Conclusion As lean moves into the non-production areas questions will continue to arise about how applicable the tools are. This article suggests that the principles of OEE can be applied equally to transactional processes as production processes, with some caveats around collection and interpretation of data. The principle benefits of this approach are the use of OEE as a ‘balanced score card’ enabling team leaders and managers to understand where the biggest improvements are to be made, be it through reducing workplace absenteeism, improving output or reducing quality defects. As with all efforts to improve productivity, it is the ‘soft stuff’ which is really hard. One should not under estimate the amount of time and effort that should be put into explaining the business drivers that require the productivity focus, and the potential benefits to both the employees and the business. Non of the concepts are new. Many companies provide incentives to reduce absenteeism, increase output and, in some cases, reduce quality defects. However, an incentive linked to OEE may be the one that best aligns with business goals.