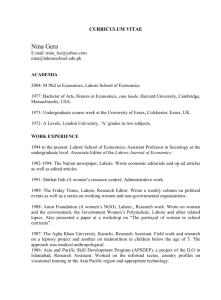

Vol.9,No.1 - Lahore School of Economics

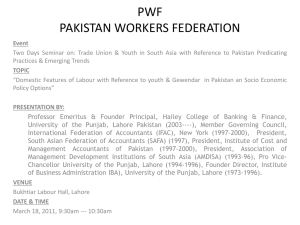

advertisement