Directing Unit of Lessons.Shawnda Moss

advertisement

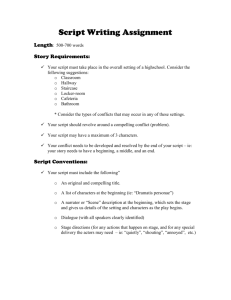

UNIT TITLE: Directing UNIT AUTHOR: Shawnda Moss UNIT OBJECTIVE: The students will demonstrate their directing skills by creating a director’s book and directing a one-act play of their choice. CURRICULUM PLACEMENT: The Directing Unit is to be used in an advanced-level theatre class with ninety-minute class periods. PRIOR STUDENT EXPERIENCE: It is expected that students will have experience with acting techniques such as blocking, objectives, and tactics as well as a knowledge of script analysis, interpretation, elements of a well-made play, and basic production design elements. 1994 NATIONAL STANDARDS: Content Standard 3: Designing and producing by conceptualizing and realizing artistic interpretations for informal or formal productions. Content Standard 4: Directing by interpreting dramatic texts and organizing and conducting rehearsals for informal or formal productions. Content Standard 5: Researching by evaluating and synthesizing cultural and historical information to support artistic choices. Content Standard 2: Acting by developing, communicating, and sustaining characters in improvisations and informal or formal productions. MAIN CONCEPTS: script analysis, production design, acting objectives and tactics, director’s concept LESSONS OUTLINE: LESSON 1: Introduction to Directing EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVE: Students will demonstrate their understanding of a director’s criteria by choosing a one-act play to direct. ASSESSMENT: Students can be assessed through their participation in the discussions, their director’s criteria responses, and their chosen script. LESSON 2: Script Analysis EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVE: Students will demonstrate their ability to take on a director’s point of view by analyzing a script. ASSESSMENT: Students can be assessed by their responses to their play’s predominant element and brief analysis. They can also be given a score for bringing two copies of their script to class. LESSON 3: Director’s Concept EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVE: Students will demonstrate their ability to create an artistic vision for their play by developing a director’s concept. ASSESSMENT: Students can be assessed through their participation in the discussions and through their partner spineline statements. LESSON 4: Production Management EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVE: Students will demonstrate their understanding of production management by designing and discussing production elements. ASSESSMENT: Students can be assessed on their dramatic metaphor/viz presentation and can also be graded on their progress with their poster design and use of practice time during the class. LESSON 5: Technical Considerations EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVE: Students will establish their technical considerations by designing and displaying their technical production design choices. ASSESSMENT: Students can be assessed through their mood presentations and their research progress. LESSON 6: Creating a Rehearsal Schedule EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVE: Students will demonstrate their knowledge of rehearsal management by creating a rehearsal schedule and basic blocking for their play. ASSESSMENT: Students can be assessed through their performance in the directing blocking exercise and their progress in creating a rehearsal schedule and blocking their plays. LESSON 7: Working with Actors EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVE: Students will demonstrate their ability to audition by participating in a cold-reading mock audition. Students will also demonstrate their ability to mark action beats by scoring their script. ASSESSMENT: Students can be assessed through their Midsummer analysis and participation in the mock auditions and directing exercise. LESSON 8: Presentation of Plays EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVE: Students will demonstrate their synthesis of a director’s preparation by presenting their director’s book. ASSESSMENT: Students can be assessed through their Director’s Book presentation and their voting sheet. NOTE: This unit is written to help students develop a director’s book for a one-act play of their choice. You may need to add a workday in order for the students to complete some of the requirements for their books. Or perhaps you will want to divide a lesson up and give them two half-days to work on their requirements. It is intended that after the unit is complete, student directors will be chosen to practice and apply what they have learned about directing. This can happen in a student-produced “Night of One-Acts” or some other performing venue. Other students can serve as assistant directors, house managers, technical crew, etc. TEXT RESOURCES: The following texts are used in this directing unit: A Sense of Direction by William Ball; New York: Drama Book Publishers, 1984. Directing Plays by Stuart Vaughn; New York: Longman Publishing Group, 1993. (my school owned a classroom set of Directing Plays, so each student in the advanced class was able to check out a textbook for the duration of the unit) DIRECTING LESSON 1: Introduction to Directing EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVE: Students will demonstrate their understanding of a director’s criteria by choosing a one-act play to direct. MATERIALS NEEDED: Directing Plays Textbook (ideally one for each student), copies of the puzzle sheet, a projection of the puzzle answer, a projector, various one-act plays and resources HOOK: Pass out the attached puzzle sheet to each student. Have them work on answering the puzzle. Encourage them to work together to find the answer. Students can cut up the puzzle pieces if they desire. Once someone figures out the puzzle, or if no one figures it out, place the answer on the overhead STEP 1: Transition – Discuss with the class how they worked to answer the puzzle. What techniques did they try? How hard was it? Liken this puzzle to directing: a director takes a whole bunch of pieces of seemingly random parts and it is his/her job to put them together in a beautiful sign (or play). STEP 2: Discussion – Pass out the Directing Plays textbooks to the students. Have them turn to page 6 and discuss with them the three essential abilities of a director: 1. Thinking and Preparation: read a play, sift it for its core, find exciting theatrical means to make it speak to audiences. 2. Working with people, Collaboration: get a group of creative people to collaborate and work to realize their vision. 3. Common sense and Hard work: get it done efficiently, on time, within budget, with everything coming together at the opening. Get the students to think about how these three abilities can be portrayed by a student in an educational setting such as this advanced theatre class: How can you prepare for directing a production? What are tips or advice in working with other people (especially people who might have different opinions and thoughts than you)? How does common sense play into directing? STEP 3: Transition – One of the first steps in preparing to direct is to choose which play you want to direct. In some scenarios, the play is chosen long before the director (find some examples of local community or university theatre seasons that are set up before directors are appointed), but in this unit students will be able to choose a one-act play that they will prepare for directing at a student-produced night of one acts. The very first question to ask yourself as a director with a potential script is: “Do I like this play enough to do it?” STEP 4: Guided Practice – Go through some play titles that the students will know (perhaps a script that they have studied in class or a local play that has recently performed). Talk with them about what specifically they liked or didn’t like about the play. Could any student direct that show based on the big question: “Do I like this play enough to do it?” Talk with the students about why they need to really, really like the play in order to direct it. Some answers might include: I’ll be spending a lot of time with it, I’ll be dissecting it, I need to feel positive about it so I can convey my enthusiasm about it, I want it to be a success, etc. STEP 5: Instruction – Teach the class that they should create a specific list of things that they respond to in a play. You could have students take turns reading aloud the few paragraphs on pages 20-21 to help them understand why they must like the play enough to do it. Also see page 21 in the textbook under the Personal Requirements heading for guidance on how to get students to figure out their own requirements for directing a play. STEP 6: Modeling – Share with the class your own personal requirements for directing a play. An example of my personal criteria include (in this order): Characters Language Theme Story Music Spectacle Some plays I would love to direct would be: Once On This Island, Noises Off! The Tempest, The Man Who Came to Dinner, Trojan Women because they fit into my order of criteria. STEP 7: Checking for Understanding – Have each student take out a piece of paper and write down their top three criteria for choosing a play to direct. Ask them to write one or two sentences after each criteria justifying/supporting their order. STEP 8: Individual Practice – Give the students the remainder of the class period to peruse the various one-act plays that you have available. Remind them that the play they choose needs to be one that they “like enough to do it!” Tell the students that they need to have the following prepared and brought to class for the next class period: Two clean copies of their chosen one-act play that are three-hole punched A three-ring binder A pencil ASSESSMENT: Students can be assessed through their participation in the discussions, their director’s criteria responses, and their chosen script. PUZZLE The six puzzle pieces shown below can be combined into a symmetrical “plus” sign. How can this be done? PUZZLE ANSWER DIRECTING LESSON 2: Script Analysis EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVE: Students will demonstrate their ability to take on a director’s point of view by analyzing a script. MATERIALS NEEDED: Directing Plays Textbook, TV and VCR/DVD, cued up film clips of various play scenes, copies of pages 27-30 of Ball’s book: Predominant Element, copies of the Director’s Book Requirements handout, optional: Due Dates Sheet HOOK: Show three-four clips from films that are based on plays. Try to find a part of the film that is more than just exposition so that there is some depth and detail involved in the clip. Some possible selections might include: A Midsummer Night’s Dream (with Kevin Kline and Michelle Pfeiffer), The Crucible (with Daniel Day Lewis and Winona Ryder), Noises Off! (with Carol Burnett and John Ritter), An Ideal Husband (with Rupert Everett and Julianne Moore). Encourage students to simply watch the film clips for an overall opinion without worrying about following the storyline. The students may want to jot down the title and a few key moments/things that stood out to them from each clip to help them keep the plays straight. STEP 1: Transition – Write the following question on the board: Does the play excite you? Have students share their responses to this question from the clips that they saw. Explain that answering this question in the affirmative is the beginning steps to developing a subjective analysis to a play. Be sure that students understand what subjective means: an individual, emotional reaction. STEP 2: Discussion – Assuming that every student responded affirmatively to the first question to at least one of the film clips, now move into the next part of the subjective analysis. Next add the following two questions on the board: Why does it excite you? Is it a good play by your standards (criteria)? Talk with class about their answers to these questions. Have them share their criteria from last class period and relate it to the clips that they enjoyed today. Remind them that they may each have a different response to these three questions, but that if they can support/justify their answers then they cannot be “wrong”. See page 22 in the textbook for reference on the subjective analysis. STEP 3: Instruction – Pass out the copies of pages 27-30 of Ball’s book that go over the Predominant Element of a play. Review with the class the elements of a well-made play from Aristotle’s Poetics: Theme Plot Language Character Spectacle Music Point out to the students that these elements can cover any style of play or any playwright. Encourage students to determine what story they want to tell; which element is most important to them so they can focus on that element and it’s place in their chosen play. As Ball says on page 30: “Narrowing one’s focus and being specific and creative within limitation leads to the most vivid success. That is why I choose one predominant element and stick to it.” STEP 4: Guided Practice – Have students pull out their script copies and three-ring binder. They should turn in one copy of their script to you (you may want to have a large three-ring binder on hand for yourself to put the scripts in) and put the other copy of the script into their binder. This will become their director’s book. Then have the students take out a half-piece of paper and write their name and their chosen play title on it. Next have them state the predominant element in that play. Then have them write a VERY brief plot synopsis of the play (eight sentences or less). STEP 5: Checking for Understanding – Once the students are done with their initial analysis of their play, have the turn to pages 30-32 in the textbook to be sure that they will be able to conduct a more thorough plot structure analysis on their own. Review the plot structure points and explain that students need to constantly look in their script for clues to the various points. STEP 6: Instruction – Pass out the Director’s Book Requirements handout. Go briefly over each requirement, but reiterate to students that you will be going over each requirement in detail as you progress through the unit. Also teach them that while you may guide them through the initial phases of creating the foundation of the requirements, you expect them to expand them in detail and type them up for the final director’s book. You may want to also create a “Due Dates” sheet to pass out alongside this handout so that students can see the timeframes they will be dealing with in the unit. STEP 7: Individual Practice – If time remains in class, allow the students to begin working on the first three requirements that have already been covered in class: Director’s Criteria, Subjective Analysis, and Play Analysis. They could also write down the royalty information that they need to supply in their books: the playwright, publishing company and contact address, and performance fees. ASSESSMENT: Students can be assessed by their responses to their play’s predominant element and brief analysis. They can also be given a score for bringing two copies of their script to class. Director’s Book Requirements Poster Design: Design a 8½ x 11 page poster for your production including color, graphics, font, etc. that fits your concept and style of the play. Royalty Information and Program Information: Include the play title, playwright, and publishing house. Add information needed for the program including the characters’ full names, any needed technical staff, setting description, special notes or thanks, etc. Director’s Criteria: What do you look for in a script? What is the predominant element of the script that you chose? Subjective Analysis: What is your initial reaction to the first reading of the script? Look at the three questions we talked about in class. Play Analysis: Write out the following elements of plot structure: a. Exposition: where, when, who, protagonist, antagonist, relationships, etc. b. Inciting Incident: what happens to change normal life? c. Rising Action: conflicts and reactions to obstacles d. Climax: what does the entire play build to? e. Falling Action: how is the play resolved? Theme and Spine: What is the play really about? What is the playwright trying to say? The spine is a statement of the play’s message. Concept: What is your vision of the play onstage? How do you see and hear this script in performance? How will you tell the story? Choose a dramatic metaphor (VIZ) for your play. Statement of Justification: Why have you selected this script to direct right now? How would directing this script add to your educational experiences? Share your wishes to direct this play for the student-produced night of one-acts. Beat Analysis: Divide your script up into beats. Mark the beats by drawing a line directly in the script to show where the beat changes. Then assign an objective to each of the major characters in each beat. Character Analysis: For each major character include the following information: super-objective (the overall activating purpose that carries the character through the play) and insight into the character’s personality, mannerisms, and style. Write down a spineline for each character (a line of dialogue that sums up that character completely). Look to these questions for guidance in discovering the characters: a. What does the playwright say about the character? b. What do other characters in the play say about each other? c. What does the character say about him/herself? Technical Considerations: How will you accomplish your play technically? What kind of budget are you looking at? What support do you need? Where will you get your materials? Scenic Design & Floorplan: floorplan to-scale on the chosen performing space, pictures or sketches of furniture and set dressings Costumes: Written descriptions along with sketches or pictures for each character (at least five for large casts). Properties: List of set props, hand props, set dressings, and any off-stage needs. Include ideas of where you will get your props from. Lighting: Describe the mood, atmosphere, color, light plot, etc. Include a mood picture with a written justification. Sound: Describe the music and special effects needed. Include a “theme music” sample with a written justification (could be used as pre-show, post-show, or underscoring music). Rehearsal Schedule: A working rehearsal schedule according to the timelines determined in class. What is to happen when and with whom? Blocking: Start to imagine how the play will move by writing in basic blocking and staging ideas with a pencil in your script. Your Director’s Book must cover each and all of the above items in great detail. Be bold and imaginative in your planning and preparation! And don’t procrastinate! DIRECTING LESSON 3: Director’s Concept EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVE: Students will demonstrate their ability to create an artistic vision for their play by developing a director’s concept. MATERIALS NEEDED: Directing Plays Textbook, copies of pages 33-36 of Ball’s book: Metaphor, examples of a dramatic metaphor (viz) for plays HOOK: Have a few examples of dramatic metaphors for plays displayed around the room. Allow the students time to examine each of the dramatic metaphors. While it would be nice to have some specific references listed here, the reality of dramatic metaphors is that the interpretation of the individual director determines what the metaphor is. So it is up to you, the teacher, to create the dramatic metaphor for a few specific plays and then display them accordingly. Some ideas that I have used in the past include: a worn piece of patchwork fabric for the musical Quilters, a color-copied picture of a stained glass window for the Greek tragedy Medea, a thorny long-stemmed rose for The Seduction from Neil Simon’s The Good Doctor, a rope tied into a noose for The Crucible, and a flashlight for Inherit the Wind. STEP 1: Transition – Have the students share their impressions of the displayed items. What were they drawn to? What interested them? What emotions did the items make them feel? Talk with them about how these inanimate objects can stir emotions and feelings and signify a certain concept or experience. Explain to them how these items connect to their respective plays. STEP 2: Instruction – Review with the students what a metaphor is: a striking comparison that does not use the words “like” and “as.” Teach them that in theatre, a dramatic metaphor (also called a viz: visual metaphor) is an object, picture, statement, photograph, sketch, or fabric that is not only “like” the production, but will be the production itself. Hand out the copies of pages 33-36 in Ball’s book and go over the ideas of the dramatic metaphor written there. STEP 3: Transition – Ask students how they could go about creating a dramatic metaphor: what information do they need to know in order to develop a visual image for a production? Some answers might include storyline, character relationships, conflict. Have them consider the idea of theme as part of that information. STEP 4: Group Practice – Divide the class into partnerships. Have each partner describe to their partner what their play is “really about.” In other words, the student should not be sharing the plot structure/storyline, but rather what the play is about through the story and characters. After listening to the description, the partner should write on a half piece of paper one sentence that states the message of the play. Then have partners switch positions so that the other partner is describing his/her play and his/her partner will add to the piece of paper his/her onesentence statement as well. STEP 5: Checking for Understanding – Have the partnerships share each other’s one-sentence statements with the rest of the class. Encourage the class to respond to the statements. STEP 6: Transition – Introduce to the class the idea that these statements are similar to a theme statement or a spineline for a play. You can have students read aloud the section under The Spine on pages 68-69 of the textbook for further explanation. Make sure that students understand that you can describe the theme of a play with a lot of language and length, but the spineline should be a brief statement. STEP 7: Modeling – Have students create a spineline for a production that they are all familiar with (perhaps a script previously studied in class or viewed together). To contrast the two concepts taught so far: spineline is a brief written statement of the theme and a dramatic metaphor or viz is a visual image of the production. STEP 8: Instruction – Now that the students understand how to determine the play’s message and how to convey that message visually, introduce the idea of a director’s concept to the students. A concept is: the central creative idea that unifies the artistic vision of a production. In other words, it is the unique way a director is going to tell the story. Using the two previous concepts to connect the concept: The spineline is a statement of what the play is about and the concept is the director’s personal interpretation of how to share that message. The dramatic metaphor can provide a visual image to support the director’s concept. Draw the visual image of the following graph on the board or on an overhead: This long line represents the entire message of the play and all of the possible interpretations of the play. This box represents the chunk designated by the director as the laws and boundaries of his/her interpretation and concept. STEP 9: Checking for Understanding – Using the play and spineline created in step five, call on a few separate students to create a concept for that play. After the concepts have been shared, have different students supply ideas of dramatic metaphors for those concepts. STEP 10: ASSIGNMENT: Assign students to come to class next period with a dramatic metaphor or viz for their production. They will be sharing their concepts with the entire class and displaying their viz’s in front of the class. ASSESSMENT: Students can be assessed through their participation in the discussions and through their partner spineline statements. LESSON 4: Production Management EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVE: Students will demonstrate their understanding of production management by designing and discussing production elements. MATERIALS NEEDED: Examples of production posters, blank paper, various magazines, art supplies such as crayons, colored pencils, markers, chalk, construction paper, etc. HOOK: Have a small table or block set up in the front of the class – on the stage if you have one – with a tablecloth laid over it. Have a table easel nearby for use. As students enter the room hand them a slip of paper with a number on it. Once the bell rings, have the student that is holding the number one come to the front of the room, put his/her dramatic metaphor or viz on the table (using the easel if the viz needs propping up) and explain his/her play concept. Go through each of the students according to the number they are holding. STEP 1: Transition – Ask the students which viz’s they were most interested in. What made that viz stand out? How did the viz support the concept? What kinds of images/feelings/emotions did the viz bring out? Encourage the students to choose a dramatic metaphor that is striking (visually or tactile arresting) and supportive of the concept. Ask the students which of the viz’s could also be incorporated in a production poster. STEP 2: Modeling – Pull out some examples of production posters: a mixture of professional Broadway, local community, and other schools will provide an array of style. Go over the various posters and discuss some of the design choices: color, font, size, graphics, etc. that all contribute to “telling the story” of the show in one visual image. STEP 3: Instruction – Assign students to create a poster design for their own show. Remind them of the production management elements that must be included in their design: Play Title Playwright Director Name Encourage them to use their imagination and creativity as they design their posters. They can use any of the art supplies you provide for them, or they can simply sketch out a rough idea on paper now and use computer graphics to polish the poster. The posters should not be bigger than 8 ½ x 11 size. Also instruct the students to collect their program information during this time. They need to create a program “front” and information that includes: characters’ full names, any needed technical staff, setting description, special notes or thanks, etc. STEP 4: Individual Practice – Spread out the art supplies and let the students create their own work stations. They can be working on their poster designs, program information, or other requirements such as Theme & Spine, Concept, Statement of Justification, and other earlier concepts taught in class. If possible, allow willing students to go to computer lab to work on their written materials or to find graphics for their poster/program. ASSESSMENT: Students can be assessed on their dramatic metaphor/viz presentation and can also be graded on their progress with their poster design and use of practice time during the class. DIRECTING LESSON 5: Technical Considerations EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVE: Students will establish their technical considerations by designing and displaying their technical production design choices. MATERIALS NEEDED: Directing Plays textbooks, access to computers with Internet access in the media center or computer lab, five instrumental music samples, five CD players/boom boxes, color gel samples, overhead projector HOOK: As the students enter the classroom, divide them into five groups. Have each group go to a section in the classroom where a CD player is sitting along with a pile of gel samples. Make sure that each CD player has one of the music samples in it. Assign each group to listen to the music sample and determine the mood that the music evokes. Once the group has decided on the mood of the piece, have them sift through the gel samples and decide which color gel fits would add to the mood and atmosphere of the piece. Once all of the groups are finished with their “creations,” have them take turns presenting their creation to the rest of the class. Have them play the music sample and put their gel color up on the overhead projector so that the color shines brightly on the screen or wall. Have a spokesman from the group describe the mood that the music evoked for the group and explain the group’s color gel choice to enhance the atmosphere. STEP 1: Transition – Discuss with the class how much more effective the atmosphere and mood can be with the addition of music and color. Ask them to cite specific moments in the group presentations that were particularly strong. What kind of emotions did certain music or colors make you feel? How can you use these effects to strengthen a play? What other technical considerations go into providing the “world of the play?” STEP 2: Instruction – Have them get out their Directing Plays textbooks and turn to pages 89-93 to discuss the design considerations presented there. Be sure to consider each of these elements within your school’s space and restraints: The Theatre Itself (the performing space that they will be designing for) Budgetary factors (how much money and support will be provided by the school) Time Factors (realistic time lines) Level of Production Skills Available (will the tech class be helping to supply materials) The Play’s Design Essentials (what do they HAVE to have in order to do the play…considering style and the genre of the play) STEP 3: Modeling – Review with the students the technical requirements for their Director’s Books. If possible, either from your stock of materials or from theatre textbooks and other resources, show them examples of costume sketches, floor plans, etc. Encourage those who students who do not consider themselves artists to peruse the Internet and magazines to find pictures and photographs that will show the types of clothing, furniture, and props they want to use in their production. STEP 4: Instruction – Tell the students that they have just practiced what they should create for the sound and lighting of their production, with the addition of a “lighting mood picture.” This picture is ANYTHING that the student finds that portrays the mood and atmosphere of their production. It need not have anything to do with their concept or setting, but rather simply convey the atmosphere and feeling that the effect of the lighting will be. The students will find a music sample that they will share with the class when they present their director’s books. It can serve as pre-show, post-show or underscoring music, and it may have words if it fits in with the concept and feeling of the show. STEP 5: Individual Practice – Because there is so much research for the students to do, give them the remainder of the class period to work on their technical considerations. Take them to a computer lab or the media center where they have access to the Internet. *If you take them to the media center you may be able to have previously arranged with the librarian to pull furniture and fashion books to be readily available to the students.* If they would rather, the students can create their floorplan or begin working on their prop lists and written descriptions of technical needs. Float around and be available as a resource to the students. ASSESSMENT: Students can be assessed through their mood presentations and their research progress. DIRECTING LESSON 6: Creating a Rehearsal Schedule EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVE: Students will demonstrate their knowledge of rehearsal management by creating a rehearsal schedule and basic blocking for their play. MATERIALS NEEDED: Directing Plays textbooks, copies of the attached content-less scenes HOOK: Put students into groups of three. Have each group write down as many elements or phases to a rehearsal schedule (things that they will do in rehearsals for a production) as they can in two minutes. These phases/elements can range from auditions to character work to final dress rehearsal. Once the two minutes is up, stand at the front of the room and begin going through the elements listed by the students and writing them on the board. Have each group share one element at a time. If that element is included on another groups list, they must cross it off (ala Scattergories). At the end of the “element sharing” the group with the most uncrossed off elements “wins.” You should have a list of rehearsal elements on the board. STEP 1: Transition – Now put the list of various elements on the board in a sequential order (simply put a number in front of the element to designate its order). You can either work forwards from auditions on or backwards from opening night. The middle elements can be in whatever order the class determines. Your list may look something like this: Auditions Off-book Callbacks Character Work Cast Meeting Working props Read-through Dry Tech Blocking Add costumes Run-through Add makeup/hair Working Run Final Dress Run Stop-and-Go Opening Night No Stop Run STEP 2: Discussion – Have the students open up their textbooks to page 181. Have someone read the quote by director Margaret Webster: “My schedule—how I use my time, how much time I devote to each phase of rehearsal—is one of my most valuable tools.” Ask the class why this statement is so important. Some answers might include: so you don’t waste time, so you’re prepared for each rehearsal, so there is a purpose to each rehearsal, etc. Skim over the next few pages (through p. 187) with the class and talk about the rehearsal management ideas presented there. STEP 3: Instruction – Assign the class to create a rehearsal schedule for their play. Guide the students to determine what the time frame is that they will be dealing with. The students should include the dates of rehearsals with specific times listed, what type of rehearsal (the phase/element) it will be, and a note of the specific characters that will be rehearsed. But before you give them time to create their schedules… STEP 4: Group Practice – in the same groups as the hook activity, have the students each choose one of the attached content-less scenes and get two copies of it. Rotating them every five-eight minutes, give them each time to direct the blocking in their chosen scene with the other two actors in their group. The scenes are extremely short, so less than ten minutes should be enough time for each director to establish a setting and a few basic movements. After the rehearsal time is up, have the group decide which of the three scenes they would like to perform for the rest of the class. STEP 5: Checking for Understanding – Have the groups perform their scene. The audience should comment on the blocking of the piece and point out specific moments where movement contributed to the feeling of the piece. STEP 6: Instruction – Teach the students that they should begin thinking of the movement of their one-act plays. They need to start visualizing how the play will be blocked and where characters will be interacting on stage. To help them begin this process, assign the students to write in basic blocking and movement in pencil directly in their script. They can use Chapter Seven in Directing Plays as a resource to determine their staging and blocking choices. STEP 7: Individual Practice – Give students the rest of the class period to work on their rehearsal schedules and blocking. Float around to help students in their work. ASSESSMENT: Students can be assessed through their performance in the directing blocking exercise and their progress in creating a rehearsal schedule and blocking their plays. Content-less Scenes A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: What was that? Don’t look. I’m only human. Maybe that’s not enough. I don’t understand. It makes me sick. Perhaps I could help. Don’t get involved. Don’t you care? Yes, I do. So? Look—there’s another one. No, don’t look. What do you want? World peace. A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: So… So… It’s up to you. Never again. O.K. That’s it? That’s it. From now on? As you say. Reconsider. Not this time. Ever? (A look—then walks off). A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: Finally! What? Let’s not pretend. Who’s pretending? It’s always the same. Only when you insist. Is it that bad? (No answer—pause—a look). Really. Well that certainly says it. Says what? Don’t make me say it in front of you. Let’s start over. If you’re sure. Finally! A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: We can’t stay here. Why not? It’s not safe. You keep saying that. Because it’s true. You’re overreacting. Not this time. It seems quiet enough. Don’t kid yourself. When do you think it will happen? Could be any moment. Or maybe never. I doubt that. Are you afraid? Even more than yesterday. At least we’re together. But for how long? Does anyone know we’re here? I’m sure of it. Did you just hear something? A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: Where have you been? Didn’t you get my message? What did it say? Does it matter now? Why shouldn’t it? How good are you at keeping a secret? Have I ever let you down before? How would I know if you did? Are you going to tell me? Do you swear not to tell anyone else? What are you getting at? Can I trust you? Who can you trust? What does that mean? You can’t figure it out? Are you insulting me? Why would I do that? Can we talk about this later? Why not right now? Why are you pressuring me? DIRECTING LESSON 7: Working with Actors EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVE: Students will demonstrate their ability to audition by participating in a cold-reading mock audition. Students will also demonstrate their ability to mark action beats by scoring their script. MATERIALS NEEDED: Directing Plays textbook, audition cuttings chosen by you from the scripts the students have chosen, copies of the scene cutting from A Midsummer Night’s Dream HOOK: Have the class arranged like a professional audition situation with you (the director) sitting behind a table and the students’ chairs facing a performing space. Using copies of scene cuttings that you chose from the scripts the student directors chose, call students up in pairs to cold-read the cutting. Depending on the size of your class, you can either have all of the students perform a cold reading or you may just have a few pairs perform. STEP 1: Transition – Talk with the class about how they felt in the mock audition. What could you, the director, do to make the audition more “actor friendly”? How can you conduct the auditions so that the actor feels like he/she is given a fair shot? How do you calm nervous actors down so they can show off their best selves? STEP 2: Instruction – Go over the casting points discussed in pages 118-125 of Directing Plays. Be sure that you have previously reviewed the material and will only focus on what you believe your students need in their particular situation as student directors: What to look for in auditions Audition material The place The process The actor “using” the director The director’s notes and symbols Audition nerves and forgetting lines The director’s reaction Callbacks Special skills, special problems Choosing STEP 3: Discussion – Along with auditions, have the students share additional ideas of working with actors. Chapter ten in the textbook and pages 59-66 in Ball’s book will give you and your students plenty of ideas to work off of. Encourage them that one of the most important ways for directors to work with actors is to help them in developing their character and objectives. STEP 4: Instruction – Explain to the students what a “beat” in a play is: a unit of conflict. See the textbook on pages 71-77 for guidance in demonstrating how to determine a beat. The following are ideas to look for to change beats: A change in subject A change in who is leading the scene Somebody enters or somebody leaves Someone finishes with one problem and takes up another Once the beat is determined then the director can work with his/her actors on creating objectives for the characters in the beat. You may need to review objectives and tactics with your students or you can refer them to pages 77-79…although be sure to tell your students that Vaughn uses the term “intentions” which equals objectives and “adjustments” which is the same as tactics. STEP 5: Guided Practice – Hand each student a copy of the attached scene cutting from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Read through the scene out loud together as a class. Then have the students individually divide the scene into beats and create an objective for Demetrius and Helena for each beat. Call on four students to act as Demetrius and Helena and two students to be the director. Have them leave the classroom to rehearse their two scenes for ten minutes. While they are gone, create with the rest of the class a generic audition form that could be used for the student produced night-of-one-acts. You may need to guide the students to come up with some of the following information to include on the form, and you should be sure that the audition form fits what your school feels is appropriate: Name Contact information: address, phone, cell, and email Grade point average Prior acting experience Technical theatre abilities Special skills and abilities STEP 6: Modeling – Have the directors and actors come back to the classroom and perform their two scenes. Discuss with the class the differences between the two scenes. Ask the directors what they did to work with their actors. Show the class how the same script and lines can be totally different depending on how the script is divided into beats and character objectives are developed. STEP 7: Individual Practice – Assign students to analyze their script and divide it into beats. Have them work on their Character Analysis requirement as outlined for their Director’s Book. Give them the remainder of the time to work on their Director’s Books. Remind students that their Director’s Books are due next class period. They should be prepared to present their books in five minutes to the rest of class by sharing the following requirements from their books: presenting the poster design summarizing the plot structure of the play conveying the concept exhibiting a mood picture (lighting) playing a section of theme music ASSESSMENT: Students can be assessed through their Midsummer analysis and participation in the mock auditions and directing exercise. A Midsummer Night’s Dream Act II, scene i DEMETRIUS: I love thee not; therefore pursue me not. Hence, get thee gone, and follow me no more. HELENA: You draw me, you hard-hearted adamant. DEMETRIUS: Do I entice you? Do I speak you fair? Or rather do I not in plainest truth Tell you I do not nor I cannot love you? HELENA: And even for that do I love you the more: I am your spaniel; and, Demetrius, Use me but as your spaniel; spurn me, strike me, Neglect me, lose me; only give me leave, Unworthy as I am, to follow you. DEMETRIUS: Tempt not too much the hatred of my spirit, For I am sick when I do look on thee. HELENA: And I am sick when I look not on you. DEMETRIUS: I’ll run from thee, and hide me in the brakes, And leave thee to the mercy of the wild beasts. HELENA: The wildest hath not such a heart as you. DEMETRIUS: I will not stay they questions. Let me go; Or if thou follow me, do not believe But I shall do thee mischief in the wood. HELENA: Fie, Demetrius! Your wrongs do set a scandal on my sex We cannot fight for love, as men may do. We should be woo’d, and were not made to woo. DIRECTING LESSON 8: Presentation of Plays EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVE: Students will demonstrate their synthesis of a director’s preparation by presenting their director’s book. MATERIALS NEEDED: CD player HOOK: Have the room set up in a performance orientation with the chairs/desks facing a performing area. Have the CD player readily accessible to the presenters in the front of the room. STEP 1: Presentations – Have each student present their Director’s Book. Watch the clock and keep the presentations to the five-minute time limit. STEP 2: Instruction – While the books are being presented, have the “audience members” keep notes on what they are watching/listening to. They will be voting at the end of the presentations on which plays should be directed for the student produced night of one-acts. STEP 3: Guided Practice – After all of the Director’s Books are presented, have the students write their top three play choices on a sheet of paper. Remind them to consider a balance of styles of plays and unique concept choices in their decisions. STEP 4: Checking for Understanding – Collect the voting sheets and the completed Director’s Books. On your own time, after grading the Director’s Books, determine and post/announce which plays will be performed for the student produced night of one-acts. ASSESSMENT: Students can be assessed through their Director’s Book presentation and their voting sheet. Director’s Book Evaluation Director ________________________________________ Grade ________/200 Play ___________________________________________________________________ Requirement Comments Poster Design Fits concept, style Royalties and Program Includes information Director’s Criteria Predominant element Subjective Analysis Three questions Play Analysis Plot structure Theme and Spine Message Concept Vision of the play Statement of Justification Why direct? Beat Analysis Beats and objectives Character Analysis Super-objective and spinelines Technical Considerations Budget and problems Scenic Design Floorplan, pictures Costumes Description, pictures Lighting Description, mood picture Sound Description, theme music Rehearsal Schedule Calendar and timeline Blocking Basic movement planned Overall: