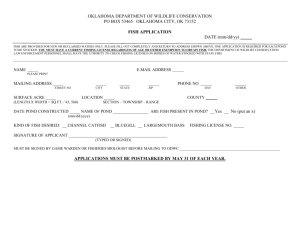

Species/Locality

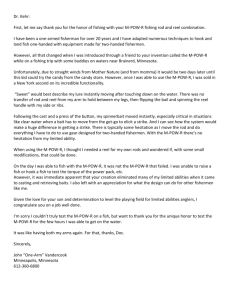

advertisement