The impact of counterfeiting - Global Congress Combatting

advertisement

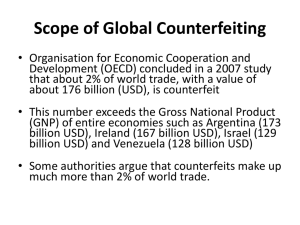

Factsheet: The impact and scale of counterfeiting The Impact Counterfeiting is generally perceived by society as a victimless crime with ‘fakes’ simply constituting a cheap alternative purchase, and seen by criminals as having a low risk of prosecution with light penalties relative to the large profits to be made. The reality is that the international trade in counterfeit products is estimated to exceed six per cent of global trade. It is not only damaging to business and investment opportunities but is also having a negative impact on society and the global economy. Trade in counterfeit goods is a lucrative and growing area and there is increasing evidence to show that in addition to the historical links between counterfeiting and organized crime, some terrorist groups are now also using this type of trade to finance their activities worldwide. The range of counterfeit products is extremely broad and the trends indicate that counterfeiters no longer confine their activities to luxury goods but increasingly are exploiting consumer goods, including everyday items such as baby food, medicines, cosmetics, aircraft and vehicle parts. This is not only illegal but constitutes a serious threat to public health and safety since these counterfeit products are not subject to safety checks. Companies and industry associations report that the quality of packaging used by counterfeiters is also improving, making it difficult for both consumers and enforcement personnel to distinguish between real and fake goods. Counterfeiters have often shown that they are well organised, adaptable and are now using more covert and sophisticated measures to avoid detection and prosecution. The problem of exports and trans-shipments of counterfeits is a growing one. Counterfeiters are increasingly shipping their products around the world for final assembly and distribution, thereby minimising the risk of seizures in the countries where components are produced. Trademark owners are increasingly finding counterfeit production and distribution operations in Russia and the former Soviet Republics, China, India, the Philippines, the Middle East and Africa and some Latin American countries. For Europe, this problem gives particular cause for concern as the enlargement of the EU and subsequent reduction in the numbers of customs officers, coupled with the extension of the border of the EU towards the east can only make the task of preventing these illegal imports far harder. Intellectual Property crime costs the public and businesses hundreds of billions of US dollars every year, and in addition to the financial issue, also Damages investment and innovation; Has potentially disastrous economic consequences for small businesses; Almost always escapes taxation, because goods are either smuggled into countries or come in with forged or invalid documents; Puts a severe strain on law enforcement agencies; Diverts government resources from other priorities and puts a strain on the limited assets available to law enforcement and other government bodies that must deal with the counterfeit problem. First Global Congress on Combating Counterfeiting – 25&26 May 2004 http://www.anti-counterfeitcongress.org 1 The Scale – General Government statistics, press reports and anecdotal accounts provided by industry associations and individual companies suggest that the scale of product counterfeiting worldwide increased in 2003. There were substantial increases in seizures of counterfeit goods in the EU, Japan and the U.S. during 2003. US customs reported that the number of seizures in 2003 increased by 12 per cent over the prior year, and the value of fakes seized also increased substantially. EU reports of seizures for 2002 and the first half of 2003 also suggest a large rise in the number of counterfeit goods recovered at EU borders. These trends are in line with a survey undertaken by the Quality Brands Protection Committee (QBPC), a coalition of more than 80 multinational companies. The majority of QBPC members reported having serious problems with exports of their brands to other countries. Trends in both the US and EU suggest a significant diversification of counterfeiting activity. In the EU, the number of fake toys intercepted by customs in the first half of 2003 was already 56 per cent higher than the total for 2002. Among the miscellaneous products seized, European and U.S. customs are increasingly seizing “disassembled” goods, i.e. components of a product (labels, bottles, corks). The counterfeiters ship the separate components into the import country, which are then re-assembled for final distribution. There also are reports of increasing trade over the internet, leading to more deliveries of counterfeits through the mail. Figures published by the European Commission at the end of 2003 show that customs seized almost 85 million counterfeit or pirated articles at the EU’s external border in 2002 and 50 million in the first half of 2003. (European Commission Nov 2003). Most counterfeit goods (66 per cent) seized in Europe in 2002 came from Asia (Thailand and China in particular). (European Commission Nov 2003). According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development as well as the European Commission, counterfeit goods are responsible for the loss of 100,000 jobs in Europe each year (European Commission 1998, OECD 1998, ICC Counterfeiting Intelligence Bureau 1997). In 2000, trade in counterfeit goods reached an estimated US$450 billion – larger than the GDP of all but 11 countries and about the same size as the total GDP of Australia. Revenues derived from counterfeiting and piracy have increased by more than 400 per cent since the early 1990s, in contrast to growth in legitimate trade of around 50 per cent over the same period. The economic impact of counterfeiting on legitimate companies is enormous - in the US, the FBI estimates losses to counterfeiting at US$200-250 billion a year. Initial estimates indicate a likely 100 per cent increase in the number of seizures of counterfeit goods entering the EU between 2001 and 2002. This follows an estimated 900 per cent increase in the number of seizures between 1998 and 2001. Counterfeiting also impacts governments and society at large; in Russia alone, an estimated US$1 billion a year in tax revenue (VAT, income tax and customs duties) goes uncollected while widespread availability of counterfeit products discourages legitimate investment. The city of New York estimated it annually loses US$500 million in state sales taxes due to the sale of counterfeit goods. First Global Congress on Combating Counterfeiting – 25&26 May 2004 http://www.anti-counterfeitcongress.org 2 Countries where counterfeiting was previously considered uncommon - such as Australia - are now increasingly victims of counterfeit exports. During the last quarter of 2003, seizures of counterfeits in Australia equaled the amount seized in the four prior quarters combined. The Scale – Sector specific Medicines The World Health Organisation estimates that counterfeit drugs account for 10 per cent of all pharmaceuticals, with the number rising to as high as 60 per cent in developing countries. The recent case of fake baby milk powder which has caused the deaths of dozens of children, and acute malnutrition of 200 others in rural China is a further example of the severe problems caused by counterfeit goods. The Chinese market is currently flooded with counterfeit goods. The state-controlled Shenzhen Evening news reported that 192,000 people died in China as a result of fake drugs in 2001. A survey in Nigeria indicated that 80 per cent of the drugs distributed in major pharmacies in the capital city of Lagos were counterfeit. 1 In India, fake medicines were estimated to occupy between 15 and 20 per cent of the market, valued at about US$1 billion.2 Consumer Goods Annual losses caused by counterfeiting of European cosmetics were estimated to exceed US$3 billion.3 According to the World Customs Organization, in Europe, it is estimated that clothing and footwear companies lose EUR 7.5 billion per year to counterfeiting, and software companies lose EUR 3.8 billion per year in Western Europe alone (WCO IPR Strategic Group, 2001). The tobacco industry estimates that counterfeit cigarettes currently occupy 3 per cent of global trade in their products, with the total number of fake cigarettes produced and sold each year being approximately 150 billion sticks. As much as 20 per cent of the clothes bought in Italy are fakes, according to a report issued by the Italian consumers association Intesa dei Consumatori in April 2004. Fake shoes and clothes reached EUR 3.13 billion (US$3.705 billion) in terms of value in 2002, and accounted for nearly 21 per cent of all counterfeits produced and marketed in Italy in the same period. On May 12 this year, the Italian customs police found 9,000 counterfeited Nike shoes (EUR 800,000 worth), shipped in a container coming from China. In 2001, illicit vodka containing methyl alcohol killed 60 people in Estonia. Automotive & Aviation Industry France’s anti-counterfeit agency estimates that up to one in ten car parts sold in Europe are fake. 1 Nigeria Reaffirms Efforts to Eliminate Fake Drugs, Xinhua General News Service, February 13, 2003, reporting on survey by the Nigerian government’s Institute of Pharmaceutical Research. 2 Herald Sun (Australia), December 20, 2003. 3 Study by the Centre for Economic Business Research, mentioned in Global Cosmetic Industry, November 1, 2003. First Global Congress on Combating Counterfeiting – 25&26 May 2004 http://www.anti-counterfeitcongress.org 3 10 per cent of gasoline sold in Bulgaria is counterfeit. The Motor & Equipment Manufacturers Association (MEMA) conducted a survey indicating that the global automotive industry loses US$12 billion to counterfeiting, thereby resulting in the loss of 750,000 jobs.4 Spurious car parts took up an estimated 37 per cent of the market in India. One company alone (General Motors) took action leading to 400 raids and the seizure of fakes valued at US$140 million. Counterfeit car parts cost automobile makers around US$12 billion annually in lost sales, enough for the industry to take on an additional 200,000 workers. Counterfeit automobile parts such as brake pads cost the auto industry alone more than US$12 billion in lost sales. The Federal Aviation Authority estimates that two per cent of the 26 million airline parts installed each year are counterfeit. Music & Multimedia Industry It is estimated that organized crime gangs earn US$4.6 billion from music piracy annually. The Business Software Alliance estimates that piracy of its members’ products costs them around US$12 billion each year. Terrorism The former leader of the Vietnamese ‘Born to Kill’ gang, serving life for murder, claimed to have made US$13 million from the sale of Rolex and Cartier watches in New York’s Chinatown in the late 1990s. The bombing of the World Trade Centre in 1993 is now thought to have been partly funded by the sale of counterfeit textiles from an outlet on Broadway. Known terrorist groups such as paramilitary groups in Northern Ireland have been strongly connected with the use of the proceeds of counterfeiting and piracy to fund their activities. 4 Automotive News, November 24, 2003. First Global Congress on Combating Counterfeiting – 25&26 May 2004 http://www.anti-counterfeitcongress.org 4