Missing: Gaddis, Novikov Telegram, Bullock, Weinberg

advertisement

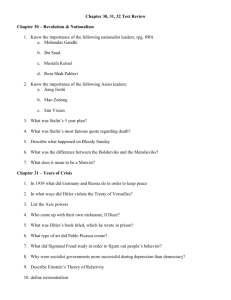

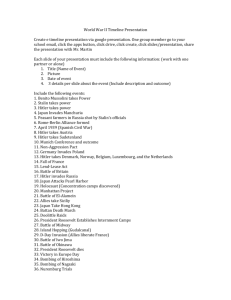

Missing: Novikov Telegram, Weinberg Gaddis, “Cold War Empires: Europe” The US and USSR are best understood within the framework of empires, in that they were each singles states that shaped the behavior of others, directly or indirectly, partially or completely, through force of intimidation, dependency, inducements, and inspiration. Furthermore, they were empires in that the imperialized also exercised influence upon the empire. After the revolution, Soviet Russia faced the disintegration of the former Russian empire as non-Russians broke away. The USSR was created by Lenin to enfranchise the minorities and Stalin later created terms that made it impossible to secede. Stalin fused Marxist internationalism and tsarist imperialism early on, equating the advance of world revolution with the expanding influence of the USSR. Though Stalin sought territorial expansions after WWII, he was careful not to involve the country in another war unless he was sure it could be won; early on, he easily demurred to the West where they made their interests clear. Still, he pushed forward where resistance was unlikely (Eastern Europe). The West initially had trouble resisting this expansion as the USSR was lionized as a wartime ally, communism had widespread appeal, and the repressive nature of the USSR was not yet widely known. The US empire came about less deliberately. Though military and economic power were in effect following WWI, isolationism at home kept the country back from international politics. This sentiment only broke down after authoritarian countries that posed a military threat appeared on the scene, namely Japan and Germany. Pearl Harbor was the defining event of the American empire because it justified the need to become a global power. After WWII, the threat was war itself and the US developed a large peacetime military and bases around the world to counter threats; it also revived the international community to removes the causes of war through institutions like the UN, IMF and World Bank. Immediately after WWII, there was still hope that the USSR could be brought into this community. Realizing this was not going to happen, containment was seen as the way to counter the Soviets and its chief instrument was the Marshall Plan. The US could not administer a large empire, so it maintained its influence through a system of autonomy. Democracy, freedom, and economic support made Soviet authoritarianism look worse in comparison. Soviet intimidation also backfired; the 1948 Czech coup and 1948 blockade of Berlin (leading to the Berlin Airlift in response) resulted in Western response that halted further expansion. Stalin attempted instead to consolidate control over already occupied territories – when Tito’s Yugoslavia showed the will and ability to resist, Stalin realized that the rest of the Soviet empire must be maintained through force. The USSR reflected the priorities of a single individual; the US reflected priorities from those incorporated under it as often as American wishes. The US empire arose from invitation, the USSR by imposition. Alan Bullock, “Hitler and the Origins of the Second World War,” 1967. -really important article, so the summary is longer Bullock, the premier biographer of Hitler, presents his view of Hitler as the primary cause of World War II. He identifies two views of Hitler in light of his foreign policy: “the fanatic” and “the opportunist.” While the first view suggests that Hitler was driven by racist and expansionist goals of expanding the German “living space” or “Lebensraum.” The second view suggests that Hitler was in practice “an astute and cynical politician who took advantage of the mistakes and illusions of others to extend German power.” Bullock argues that Hitler must be understood as “both fanatical and cynical:” he was driven by set goals but was not constrained by his plans, constantly and opportunistically improvising to reach his ultimate ends. The article follows Hitler’s actions from his becoming Chancellor in 1933 to his instigating a full fledged war by the 1940s. In the early years of his rule, “Hitler’s foreign policy was cautious.” He appealed to “the forms of legality” and “Wilsonian principles of national self-determination” to appease Europe while he tried to solidify German power, first by leaving the Disarmament Conference. Hitler soon broke out of diplomatic isolation and resumed contact with other powers. Attention paid by Europe to other events between 1935-37, including Mussolini’s Abyssinian crisis and Spain’s civil war, allowed Hitler to reoccupy the Rhineland with little resistance. By 1938 he had begun to replace his conservative diplomats who did not fit his new, opportunistic style. By this point, German national pride had returned. Rearmament was believed to be much more extensive than it in fact was. Its economy was far from being maximized towards military production. This was because Hitler recognized that a long war would subject Germany to blockades and shortages of resources, and the only successful option for future wars was “a series of short campaigns in which surprise and the overwhelming force of the initial blow would settle the issue….” Rather than being geared to a long-term plan of converting to war production, the economy was positioned to produce quick results, rapid and full-force wars called blitzkrieg. At the Hossbach meeting, Hitler told his war commanders and top advisors that the overthrow of Austria and Czechoslovakia was necessary, but Bullock argues that he was only posturing and had not settled on war as his only option. With Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Poland, Hitler presented the threat of war to force action by England or France; the first action was always avoided by England and France, leaving Hitler to his political maneuverings. Austria was forced to make political concessions and then quickly subdued, while the Slovaks and then Czechs folded to the pressure of the threat of invasion and allowed themselves to be absorbed. Hitler believed he was on a “time table,” however, for pursuing conquest of Europe, and by 1943-45 the rest of Europe would be armed and prepared to defeat him. Hitler had also rearmed Germany to a level capable of fighting France and Britain, he was more confident than before of success, and he had secured peace with the Soviets. In 1939, The same tactic of the threat of invasion in Poland indeed led to invasion, but Britain unexpectedly to Hitler announced that they would not disregard this final action. The following year, Hitler’s preemptive attack against France and Britain was another success, and France was taken. Hitler believed that the invasion of Russia would be successful and would secure his power, but his last gamble failed. These are the key events that demonstrate Bullock’s thesis that Hitler’s actions were both opportunistic and goal-oriented. According to Bullock, Hitler foreign policy was the same before and during the war, “using each victory as the basis for raising the stakes in a still bolder gamble next time.” Key Quotes: “…that extraordinary combination of consistency in aim, calculation, and patience in preparation with opportunism, impulse, and improvisation in execution which I regard as characteristic of Hitler’s policy.” “But Hitler’s opportunism was doubly effective because it was allied with unusual consistency of purpose.” The Half-Armed Peace - by AJP Taylor The explanation that World War II was caused by the return of states to rely on armed strength, diplomacy and alliances is so broad as to not convey anything meaningful about the causes of WWII. Great analogy "Every road accident is caused by . . . the invention of the internal combustion engine." Something specific caused WWII because statesmen and dictators alike had used blustery language before and not gone to war. Hitler was only planning to go to war against the Soviets and Moussolini did not want to go to war at all. He did only when he thought it was a sure thing. Some people think that the capitalists were driving toward war, but they were the countries and peoples most against it. Hitler and Mussolini were not driven by economic motives, but by their appetite for success by whatever means possible. H & M were fascist and broke agreements and violated standards openly and brashly. Then, they made further agreements and broke them again. And other states kept on trying to give them more chances. Mussolini conquered Abyssinia and nothing happened to him from the League of Nations. After Hitler ended the Locarno treaties by remilitarizing the Rhineland, he systematically tries to undo every unfavorable term in the Treaty of Versailles. This was the main greivance of the German population as well. With every restored German stand, he grew in standing, until the treaty was torn to shreds. Then he had to set a new goal: Austria which he wanted to make a puppet government. The War for Danzig – by AJP Taylor British offered to arrange negotiations between Poland and Germany, if Hitler promised peace, but the British knew that the Poles would not make concessions (the Germans wanted the city of Danzig) without the threat of war. The British could not put pressure on Poland because of the British public, and the Americans would not put pressure either. All the British could do was wage a punitive war. Hitler offered direct negotiations with Poland but they refused. Germany offered Poland "liberal" terms but they again refused even over British urging that they accept. This created a wedge between the the West and Poland which Hitler then took advantage of by attacking. Even then, the Poles refused to even send a negotiating party. Hitler bombed Warsaw and even though the British and French had been pledged to protect Poland, they did nothing but issue remonstrations. The UK and France tried to get a peace conference going but that was a doomed to failure and both countries declared war after a bit of foot dragging. Kissinger, “The End of Illusion” and “Stalin’s Bazaar”: p. 288-318, 332-349 Kissinger's key thesis in this section concerns the relationship between the two primary, competing explanations for the causes of World War II: "That Germany would emerge from [the 1930s] as the strongest nation on the Continent was inevitable; the orgy of killing and devastation that it unleashed was the work of one demonic personality." In Kissinger's view, Germany was destined to rise to power for structural reasons at the end of World War I. However, the violent means by which this happened could largely be attributed to Hitler. According to Kissinger, Hitler's greatest foreign policy success was in tricking Western nations into believing that he was aiming to fulfill the principles of the Versailles system, when in fact he was just fulfilling his quest for world domination. In fact, Hitler probably based many national decisions based on limitations in his personal life. Structural factors contributed to Hitler's ability to rise. For example, France and Britain persisted on disarmament during the German rise to power; meanwhile, Germany had withdrawn from the League of Nations and continued to re-arm without serious disruption. Further, the weak resistance of Eastern European states ( Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Romania) allowed for eastward German expansion. While there was initially a budding alliance between Britain, France, and Italy, British and French policy during Italian aggression in Abyssinia ultimately pushed Italy toward the German side (even though British and French action was largely ineffectual in Abyssinia anyway). Meanwhile, the Allies stayed quiet while Germany consistently contravened provisions of Versailles and Locarno, by invading the Rhineland, supporting Spanish revolutionaries, annexing Austria, and threatening Czechoslovakia on behalf of their domestic Germans. British opposition to Germany only solidified following the Munich Pact, which surrendered key regions of Czechoslovakia to the Germans. The latter section of this reading briefly discusses how Western exclusion of Stalin strangely pushes Stalin and Hitler closer together. The key point of this section is that Russia viewed Germany in the same moral terms as it viewed Britain or France: all represented capitalist evils. That said, Stalin also subscribed to realpolitik: he sought to extract assistance from the capitalist world, without necessarily making peace with it either. Key quote: "To resist the impending German threat, Britain's leaders should have confronted Hitler and conciliated Mussolini. They did just the opposite: they appeased Germany and confronted Italy." Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Extremes: A History of the World, 1914-1991, “The Age of Total War” World War II has produced much less literature than World War I, as most historians view the causes of the second war as much more simple than the first: Germany, Japan, and Italy were the aggressors. Even more simply, we might say the war was caused by Adolf Hitler (1st image). The Allies did not want the war, and did what they could to avoid it. The real causes of World War II were obviously not quite so simple. Germany was understandably upset with the Treaty of Versailles, and Japan and Italy were not content with their situations, despite being victors in World War I. Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931, Italy went in to Ethiopia in 1935, and Germany entered Austria (1938), Czechoslovakia (1939), and Poland (1939). While the Allies did not want a war, Hitler glorified, desired, and embraced it. Nevertheless, Hitler could not have originally wanted a war against both the USA and the USSR. And Japan would have liked to have achieved its Asian objectives without a general war with the USA. “Germany overran Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, and France with ridiculous ease.” By 1940, the war in Europe was essentially over. The war was revived when Hitler foolishly attacked the USSR in June 1941. Germany’s initial advances into Russia were as swift as those in the West. The German armies were halted and forced to surrender at Stalingrad. At this point Germany’s chances were crushed, as it was not equipped to fight a long war against the combined resources of the Allies. Japan’s fate was similar: it had no chance against the superior resources of the United States. The Allied victory in 1945 was complete and unconditional. The defeated countries were occupied and no formal peace treaties were signed, as no authorities were recognized in Germany or Japan. The losses from the war are unknown and incalculable. Total deaths are thought to be 3-5 times more than WW I. Between 10-20% of the total population in USSR, Poland, and Yugoslavia is thought to have died, and between 4-6% in Germany, Italy, Austria, Hungary, Japan, and China. World War II and modern warfare are unique in their scope: We take it for granted that modern warfare involves all citizens and mobilizes most of them; that it is waged with armaments which require a diversion of the entire economy to produce them, and which are used in unimaginable quantities; that it produces untold destruction and utterly dominates and transforms the life of the countries involved in it. War also revolutionized management, and accelerated the rate of technical advance. World War II actually benefited the U.S. economy (10% growth rate – the highest ever before or since), but it completely devastated the USSR. Most countries fell somewhere in between this spectrum, but closer to the USSR. Scott D. Sagan, “The Origins of the Pacific War,” pp. 893-914, 917-18, 919-920, 922. The essay traces the decision-making process between 1940-41 leading up to war between the US and Japan. Contrary to popular belief, Sagan states that the Japanese decision to attack the militarily superior US (called a “crazy aberration”) was rational. He considers the Pacific War a mutual failure of deterrence. The war was mainly a question of natural resources. Japan needed oil—which it obtained from the US—to fuel its warships. At the time, the US attempted to contain Japanese imperialist ambitions through the threat of 1) oil embargo and 2) military intervention. The main idea was the following: Japan wanted to attack the Dutch Indies for oil (in the case of a US embargo), but it was fearful of US intervention if Japan attacked European colonies. Japan was very clear that launching a war against the US would be disastrous—it therefore resorted to diplomatic means until conflict seemed inevitable. The decision-making process boiled down to three questions: Should Japan accept the American demand for complete troop withdrawals from China? Second, could British and Dutch territories be attacked to acquire the needed oil supplies, without American intervention? Third, how could Japan win a war against the United States? The main point of tension was between US troops stationed in Pearl Harbor and Japanese troops that moved into Indochina. Sagan argues that a large part of the impetus for the war was unintentional: when Roosevelt finally decided to “freeze” Japanese assets, he meant only to exhibit US power and not to actually limit oil to Japan. However, the situation reached a point where the removal of the embargo would seem like appeasement. Japan therefore became a “terminally ill” patient, faced with accepting a desperate peace (where it would have to give up gains in the Pacific) or fighting a desperate war. With the general belief that conflict was inevitable and that British and US forces were only becoming stronger, the Japanese decided to strike first. As Prime Minister Tojo proclaimed, “At the moment, our Empire stands at the threshold of glory or oblivion.” Traditional deterrence theory claims that deterrence only works with capability and credibility—a credible threat and the capability to carry it out. Therefore, the potential costs of war must be extremely high while the probability of victory is low. However, deterrence—as shown by the situation with Japan—will not work when the costs of not going to war are even higher. The outbreak of the Pacific War can be seen as a country that had made rational, calculated decisions, launching a war out of desperation. Kissinger, Diplomacy, Ch. 17: The Beginning of the Cold War (423-445). Potsdam was a failure. Stalin only understood territorial gain; Churchill recognized this and advocated a Realpolitik approach to defending against Russian expansion that was lost on Truman. "American negotiators acted as if the mere recitation of their legal and moral rights ought to produce the results they desired. But Stalin needed far more persuasive reasons to change his course…. No American statesman was prepared to issue the kind of threat or pressure which Churchill envisioned and which Stalin's psychology would have required." (436) For example, Stalin kept his troops in Eastern Europe for bargaining power and Truman refused (against Churchill's urgings) to keep allied troops as far east as they had gone in Central Europe for bargaining power. Stalin, in turn, installed Soviet puppets in Yugoslavia, Poland, Czechoslovakia and Albania and exerted significant influence in Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary and Finland. Truman insisted on trying to maintain the feeling of goodwill between the America and Russia that had existed during the war. When it became clear that Stalin was intractable, American opinion took the leap from "pure goodwill to indiscriminate suspiciousness" (444). This was the start of the cold war. Summary of NSC-68: This report was issued during the Truman presidency during the budding of the Cold War, and is though to have shaped government action in the Cold War for the next 20 years. It was de-classified in 1977. NSC-68 would make the case for a US military buildup to confront what it called an enemy "unlike previous aspirants to hegemony... animated by a new fanatic faith, antithetical to our own." The Soviet Union and the United States existed in a bi-polar world, in which the Soviets wished to "impose its absolute authority over the rest of the world." This would be a war of ideas in which "the idea of freedom under a government of laws, and the idea of slavery under the grim oligarchy of the Kremlin" were pitted against each other. Therefore, the US as "the center of power in the free world," should build a international community in which American society would "survive and flourish" and pursue a policy of containment. ID Terms Rhineland: the geographic region on both sides of the Rhine River. The western part of the Rhineland was occupied by the Entente after World War I, and then demilitarized according to the Treaty of Versailles. German military forces reoccupied the Rhineland in 1936 in order to test the diplomatic will of the rest of Europe, which did not respond due to its attitude of appeasement. Molotov-Ribbentrop Agreement: a non-aggression treaty between Germany and the USSR signed in 1939. Also referred to as the Hitler-Stalin pact, German-Soviet Non-aggression Pact or Nazi-Soviet pact. Although it was a non-aggression treaty, the pact included a secret protocol involving the division of Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Romania into spheres of interest for Germany and the USSR. The agreement lasted until June 1941, when Germany invaded the USSR in Operation Barbarossa. Four Policemen: the four major Allies of WW II, the United States, the United Kingdom, the USSR, and China. The term was coined by FDR. George Kennan: a key Cold War figure most notable for his theory of “containment.” His theories inspired much of Truman’s policies towards the USSR. Pearl Harbor: US naval base in Oahu, Hawaii. Surprise Japanese attack spurred US involvement in WWII and started war in Pacific theater. December 7, 1941: “a day that will live in infamy.” (Refer to summary above for more information on outbreak of Pacific War). Munich Pact: agreement on the Sudetenland crisis in which the Sudetenland was ceded to the Germans. Widely regarded as an appeasement to Nazi Germany, practiced to avoid another world war. The Sudetenland was occupied by a German-speaking population that did not want to be a part of Czechoslovakia based on principle of self-determination. Stepping stone for further German demands and eventually German takeover of Czechoslovakia. Axis Powers: Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, Empire of Japan and allied states. States opposed to Allies during WWII. Formed during the Tripartite Treaty, joined by Hungary, Romania, Slovakia, and Bulgaria. The Long Telegram US diplomat George Kennan defined in 1947 what would become the bedrock of American Cold War policy: (i) The Soviet Union perceived itself to be at eternal war with capitalism; (ii) Soviet aggression was not fundamentally aligned with the Russian people's views or with economic reality, but rather in historic Russian xenophobia and paranoia. Kennan also accurately predicted most of the tactics and strategies that the Soviet Union would employ during the Cold War Containment. After WWII the primary goal of the United States became to prevent the spread of Communism to non-Communist nations; that is, to "contain" Communism within its borders. The Truman Doctrine aimed at this goal, and containment was one of its key principles. This led to American support for regimes around the world to block the spread of communism. The epitome of containment may have been domino theory, which held that allowing one regional state to fall to communism would threaten the entire region. Marshal Plan The primary plan of the United States for rebuilding the allied countries of Europe and repelling communism after World War II. The initiative was named for United States Secretary of State George Marshall and was largely the creation of State Department officials, especially William L. Clayton and George F. Kennan. The Marshall Plan has also long been seen as one of the first elements of European integration, as it erased tariff trade barriers and set up institutions to coordinate the economy on a continental level. One intended consequence was the systematic adoption of American managerial techniques. Iron Curtain The "Iron Curtain" was the boundary which symbolically, ideologically, and physically divided Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II until the end of the Cold War, roughly 1945 to 1991. The term was coined by Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels and made famous by Winston Churchill. Hossbach Memorandum - the summary of the minutes of a meeting on November 5, 1937 between Adolf Hitler and his military leadership, laying out his plans to precipitate an aggressive war that would eventually be known as World War II in Europe. The Memorandum is often used by intentionalist historians to prove that Hitler had planned the Second World War and some of the events which led to it. However structuralist historians would argue that the document shows no such plans. They would also contend that Britain and France's appeasement of Hitler (in his remilitarization of the Rhineland in March 1936 and the Anschluss of Austria in March 1938) had given him the confidence to exploit the situations and to move on to Czechoslovakia and Poland. This appeasement only seemed to have ended when war was declared on Hitler by Britain and France on 3 September 1939. Sudetenland- After 1933, the Sudeten-German party (SdP) pursued a policy of escalation. Party leader Konrad Henlein had secretly formed a pact with the Nazi Party now ruling in Germany and would gradually increase his demands so that Hitler could reap the fruits of the conflict. Immediately after the Anschluss of Austria into the Third Reich in March 1938, Hitler made himself the advocate of ethnic Germans living in Czechoslovakia, triggering the "Sudeten Crisis". The Nazis, together with their Sudeten German allies, demanded incorporation of the region into Nazi Germany to escape oppression. While the Czechoslovakian government mobilised its troops, the Western powers urged it to comply with Germany believing that they could prevent or postpone a general war by appeasing Hitler. Conference at Yalta- wartime meeting from February 4, 1945 to February 11, 1945 between the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union — Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and Joseph Stalin, respectively.Roosevelt was lobbying for Soviet support in the Pacific War concerning the invasion of the Empire of Japan; Churchill was pressing for free elections and democratic institutions in Eastern Europe (specifically Poland), while Stalin was attempting to establish a Soviet sphere of influence in Eastern Europe which the Soviets thought was essential to Soviet national security. There was an agreement that the priority would be the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany. After the war, Germany would be split into four occupied zones, with a quadripartite occupation of Berlin as well, prior unification of Germany. Potsdam conference - Issuance of a statement of aims of the occupation of Germany by the Allies: demilitarization, denazification, democratization and decartelization. Division of Germany and Austria respectively into four occupation zones (earlier agreed in principle at Yalta), and the similar division of each's capital, Berlin and Vienna, into four zones. Agreement on the prosecution of Nazi war criminals. Reversion of all German annexations in Europe after 1937, these included Sudetenland, Alsace-Lorraine, Austria and the westmost parts of Poland Adolf Hitler: dictator of Germany and leader of the Nazi party leading up to and during World War II. Winston Churchill: prime minister of Great Britain during World War II. Predicted the Cold War long before it happened. Rapallo Conference: convened by the Allies during World War I in 1917 after their defeat in Italy at the Battle of Caporetto by Germany. This was significant because the conference resolved to form a "supreme allied council" at Versailles to coordinate the action plan of the Allies. Benito Mussolini: fascist leader in Italy leading up to and during World War II. He originally did not like Hitler and tended toward the Allies, until the Allies rebuffed Italy's aggression in Abyssinia. Allied Powers – The alliance of the USA, Britain, the USSR and others against Germany and the other Axis powers in WWII. Its primary leaders were President Franklin Delano Roosevelt of the US, Prime Minister Winston Churchill of Britain, and Josef Stalin of the Soviet Union. France and China were later considered Allied Powers. Josef Stalin – The General Secretary of the Soviet Union from 1922 -1953, consolidated power as a dictator from 1928 onwards. Killed many of his own people in “purges.” Initially made a treaty with Hitler but after the German invasion, joined the Allied Powers in WWII. Franklin D. Roosevelt – The President of the U.S. from 1933-1945. Instituted his New Deal policy of government programs in response to the Great Depression. Served during America’s entrance into WWII after Pearl Harbor. Died in office in his 4th term. Harry S. Truman – President of the U.S. from 1945-1953. Served as vice-president under FDR, succeeded to the Presidency after FDR’s death. Concluded victory against Germany in WWII. Forced Japanese surrender by using the newly invented atomic bomb at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Under Truman, the Marshall Plan provided economic aid for the rehabilitation of Europe, while the Truman Doctrine shifted America foreign policy regarding communism and the USSR to a policy of containment. Comintern - The Communist International was an organization intended to fight "by all available means, including armed force, for the overthrow of the international bourgeoisie and for the creation of an international Soviet republic as a transition stage to the complete abolition of the State." It was founded in 1919 but dissolved in 1943 to reassure the USSR’s allies. NSC-68 - Signed by Harry Truman in 1950, this backed up Kennan’s policy of containment with significant peacetime military spending (up to 20% GDP) to protect the US and its allies from Soviet aggression anywhere in the world. Berlin Blockade – In 1948, Stalin closed off Berlin to the West after the proposal of a separate West German state and the introduction of currency to the area which the USSR had no control over. The Berlin Airlift came in response, forcing Stalin to lift the blockade and halting Soviet territorial expansion in Western Europe.