Down

advertisement

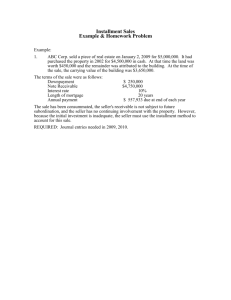

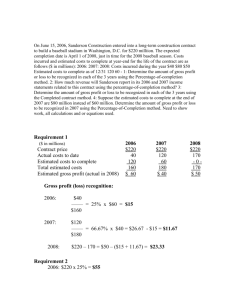

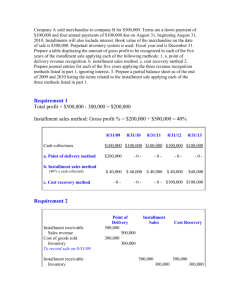

CHAPTER 5 Income Measurement and Profitability Analysis Overview The timing of revenue recognition is critical to income measurement. Revenue affects income, and, under the matching principle, expenses are recognized in the period in which the related revenues are recognized, so revenue recognition determines the recognition of some expenses as well. The focus of this chapter is revenue recognition. We also continue our discussion of financial statement analysis. Learning Objectives ● LO5-1 Discuss the timing of revenue recognition, list the two general criteria that must be satisfied before revenue can be recognized, and explain why these criteria usually are satisfied when products or services are delivered. ● LO5-2 Discuss the principal/agent distinction that determines the amount of revenue to record. ● LO5-3 Describe the installment sales and cost recovery methods of recognizing revenue and explain the unusual conditions under which these methods might be used. ● LO5-4 Discuss the implications for revenue recognition of allowing customers the right of return. ● LO5-5 Identify situations requiring recognition of revenue over time and demonstrate the percentage-of-completion and completed contract methods of recognizing revenue for long-term contracts. ● LO5-6 Discuss the revenue recognition issues involving multiple-deliverable contracts, software, and franchise sales. ● LO5-7 Identify and calculate the common ratios used to assess profitability. ● LO5-8 Discuss the primary differences between U.S. GAAP and IFRS with respect to revenue recognition. Lecture Outline Part A: Revenue Recognition I. Revenue Recognition in General A. FASB definition: “Revenues are inflows or other enhancements of assets of an entity or settlements of its liabilities (or a combination of both) from delivering or producing goods, rendering services, or other activities that constitute the entity’s ongoing major or central operations.” In other words, revenue tracks the inflow of net assets that occurs when a business provides goods or services to its customers. (T5-1) B. The realization principle requires that two criteria be satisfied before revenue can be recognized: Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-1 1. The earnings process is judged to be complete or virtually complete. 2. There is reasonable certainty as to the collectibility of the asset to be received. C. Staff Accounting Bulletin No.’s 101 and 104 summarized the SEC’s views on revenue recognition. The bulletins provide additional criteria for judging whether or not the realization principle is satisfied: 1. Persuasive evidence of an arrangement exists. 2. Delivery has occurred or services have been rendered. 3. The seller’s price to the buyer is fixed or determinable. 4. Collectibility is reasonably assured. D. IFRS revenue recognition concepts focus on transfer of economic benefits. IFRS allows revenue to be recognized when the following conditions have been satisfied: 1. The amount of revenue and costs associated with the transaction can be measured reliably, 2. It is probable that the economic benefits associated with the transaction will flow to the seller, 3. (for sales of goods) the seller has transferred to the buyer the risks and rewards of ownership, and doesn’t effectively manage or control the goods, 4. (for sales of services) the stage of completion can be measured reliably. These requirements are similar to U.S. GAAP, and revenue typically is recognized at a similar point under IFRS and U.S. GAAP. (T5-2) II. Revenue Recognition at Delivery A. While revenue usually is earned during a period of time, revenue often is recognized at one specific point in time when both revenue recognition criteria are satisfied. B. It is important to determine whether a seller is a principal of an agent. (T5-3) 1. A principal has primary responsibility for delivering a product or service, and typically is vulnerable to risks associated with delivering the product or service and collecting payment from the customer. If the seller is a principal, it should recognize as revenue the gross (total) amount received from a customer. 2. An agent does not have primary responsibility for delivering a product or service, and typically is not vulnerable to risks associated with delivering the product or service and collecting payment from the customer. If the seller is an agent, it should recognize as revenue only the commission it receives for facilitating the sale. C. Revenue from the sale of products usually is recognized at the point of product delivery, but can be delayed past delivery if material uncertainties exist or allowed prior to delivery for long-term contracts. (T5-4, T5-5) D. Service revenue often is recognized over time, in proportion to the amount of service performed. If there is one final service that is critical to the earnings process, revenues and costs are deferred and recognized after this service has been performed. III. Revenue Recognition after Delivery A. Significant uncertainties about cash collection could cause a delay in recognizing revenue from the sale of a product or a service. (T5-4, T5-5) B. Installment sales © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-2 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e 1. Revenue recognition for most installment sales takes place at the point of delivery, because reliable estimates of potential uncollectible amounts can be made. 2. When exceptional uncertainty exists, two accounting methods are available: a. The installment sales method. b. The cost recovery method. 3. The installment sales method recognizes gross profit by applying the gross profit percentage on the sale to the amount of cash actually received. (T5-6) 4. The cost recovery method defers all gross profit recognition until cash equal to the cost of the item sold has been received. (T5-7) C. Right of Return (T5-8) 1. When the right of return exists, revenue cannot be recognized at the point of delivery unless the seller is able to make reliable estimates of future returns. In most retail situations, reliable estimates can be made and revenue and costs are recognized at point of delivery. 2. Otherwise, revenue and cost recognition is delayed until the uncertainty is resolved. IV. Revenue Recognition prior to Delivery A. It often is desirable to recognize revenue over time for long–term contracts. (T5-4, T5-5) The types of companies that make use of long-term contracts are many and varied, although they are most prevalent in the construction industry. (T5-9) In these situations, there are two methods of accounting for revenue and expense recognition: 1. The completed contract method. 2. The percentage-of-completion method. B. Much of the accounting is the same under both of these methods (T5-10, T5-11) 1. All costs of construction are recorded in an asset (inventory) account called construction in progress. 2. Period billings are credited to billings on construction contract, a contra account to the construction in progress account. This serves to reduce the carrying value of the physical asset (construction in progress) when a financial asset (accounts receivable) is also recognized; otherwise the project would be double-counted on the balance sheet. 3. Construction in progress is debited for the amount of gross profit recognized. The same total amount of gross profit is recognized under the two methods – the only difference is timing. (T5-11, T5-12) C. The completed contract method is equivalent to recognizing revenue at the point of delivery, that is, when the project is complete. 1. No revenues or expenses are recognized until the project is complete. (T5-11, T5-12) 2. The completed contract method does not properly portray a company's performance over the construction period and should only be used in unusual situations when forecasts of costs to complete the project are highly uncertain. D. The percentage-of-completion method allocates a fair share of a project's revenues and expenses to each reporting period during construction. How is that fair share determined? (T5-13) 1. The allocation of project profit is accomplished by estimating progress to date. 2. Progress to date (the percentage of completion) can be estimated as the proportion of the project's cost incurred to date divided by total estimated costs, by project Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-3 milestones, or by relying on an engineer's or architect's estimate. The “cost to cost” approach is most common. 3. To determine periodic gross profit (revenues less expenses), the percentage of completion is multiplied by estimated gross profit to determine gross profit earned to date, and then the current period's gross profit is determined by subtracting from this amount the gross profit recognized in previous periods. 4. Periodic revenues are determined by multiplying the percentage of completion by the total contract price and then subtracting revenue recognized in prior periods. In most cases, the cost of construction equals the construction costs incurred during the period. (T5-14) E. Balance sheet effects: Construction in progress is compared to billings on construction contract. (T5-15) 1. A debit balance indicates costs (plus profits for the percentage-of-completion method) in excess of billings and is reported as an asset. 2. A credit balance indicates billings in excess of costs (plus profits for the percentage-ofcompletion method) and is reported as a liability. F. Long-term contract losses 1. A loss could occur on a profitable project if the estimated costs to complete were underestimated in prior periods. 2. An estimated loss on a long-term contract is fully recognized in the first period that the loss is anticipated, regardless of the revenue recognition method used. (T5-16) 3. Recognized losses on long-term contracts reduce the construction in progress account. G. IFRS: IAS No. 11 governs revenue recognition for long-term construction contracts. (T5-17) 1. Like U.S. GAAP, the international standard requires the use of percentage-ofcompletion accounting when estimates can be made precisely. 2. Unlike U.S. GAAP, the international standard requires the use of the cost recovery method rather than the completed contract method when estimates cannot be made precisely enough to allow percentage-of-completion accounting. a. Under the cost recovery method, contract costs are expensed as incurred, and an exactly offsetting amount of contract revenue is recognized, such that no gross profit is recognized until all costs have been incurred. b. Under both the cost recovery and completed contract methods, no gross profit is recognized until the contract is essentially completed, but revenue and construction costs will be recognized earlier under the cost recovery method than under the completed contract method. V. Industry-Specific Revenue Issues A. Multiple-element arrangements (T5-18) 1. If a software arrangement (sale) includes multiple elements, the revenue from the arrangement should be allocated to the various elements based on the relative fair values of the individual elements (Vendor-specific objective evidence”). 2. More generally, if an arrangement contains multiple elements, revenue should be allocated to individual deliverables if that qualify for separate revenue recognition (e.g., they must have value on a stand-alone basis). Otherwise, revenue is delayed until © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-4 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e completion of later deliverables. The revenue is allocated based on relative selling prices, and those prices can be estimated if they are not available. 3. IFRS: IAS No. 18 is the general revenue recognition standard in IFRS. There is not much guidance about multiple-element contracts or industry-specific revenue recognition in IFRS. B. In a franchise sale, the fees to be paid by the franchisee to the franchisor usually comprise (1) the initial franchise fee, and (2) continuing franchise fees. (T5-19) 1. GAAP requires that the franchisor has substantially performed the services promised in the franchise agreement and that the collectibility of the initial franchise fee is reasonably assured before the fee can be recognized. 2. Continuing franchise fees are paid to the franchisor for continuing rights as well as for advertising and promotion and other services over the life of the agreement and are recognized by the franchisor as revenue in the period received, which corresponds to the periods the services are performed. Part B: Profitability Analysis I. Activity Ratios (T5-20) A. Activity ratios measure a company's efficiency in managing its assets. B. The asset turnover ratio measures a company's efficiency in using assets to generate revenue and is calculated by dividing a company's net sales or revenues by the average total assets available for use during the period. C. The receivables turnover ratio offers an indication of how quickly a company is able to collect its accounts receivable. 1. The ratio is calculated by dividing a period's net credit sales by the average net accounts receivable. 2. An extension of this ratio is the average collection period, which is computed by dividing 365 days by the receivable turnover ratio. D. The inventory turnover ratio measures a company's efficiency in managing its investment in inventory. 1. The ratio is calculated by dividing the period's cost of goods sold by the average inventory balance. 2. An extension of this ratio is the average days in inventory, which is computed by dividing 365 days by the inventory turnover ratio. II. Profitability Ratios (T5-21) A. Profitability ratios assist in evaluating various aspects of a company's profit-making activities. B. The profit margin on sales measures the amount of net income achieved per sales dollar and is computed by dividing net income by net sales. C. The return on assets (ROA) indicates a company's overall profitability. 1. It is calculated by dividing net income by average total assets. 2. The return on assets can also be computed by multiplying the profit margin on sales by the asset turnover. D. The return on shareholders' equity measures the return to suppliers of equity capital. It is calculated by dividing net income by average shareholders' equity. Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-5 III. DuPont Framework (T5-22) A. The DuPont Framework helps identify how profitability, activity, and financial leverage trade off to determine return to shareholders. In equation form, it is: Return on equity = Profit margin X Net income Ave. total equity = Net income Total sales X Asset turnover Total sales Ave. total assets X Equity multiplier X Ave. total assets Ave. total equity B. Because profit margin and asset turnover combine to equal return on assets, the DuPont framework can also be written as: Return on equity = Return on assets Net income Ave. total equity = Net income Ave. total assets X Equity multiplier X Ave. total assets Ave. total equity Appendix: Interim Reporting A. Interim reports are issued for periods of less than a year, typically as quarterly financial statements. B. With only a few exceptions, the same accounting principles applicable to annual reporting are used for interim reporting. C. Complete financial statements are not required for interim reporting, but certain minimum disclosures are required: 1. Sales, income taxes, extraordinary items, cumulative effect of accounting principle changes, and net income. 2 Earnings per share. 3 Seasonal revenues, costs, and expenses. 4. Significant changes in estimates for income taxes. 5. Discontinued operations, extraordinary items, and unusual or infrequent items. 6. Contingencies. 7. Changes in accounting principles or estimates. 8. Significant changes in financial position. SUPPLEMENT: WHERE WE’RE HEADED A. Core revenue recognition principle: An entity shall recognize revenue to depict the transfer of goods or services to customers in an amount that reflects the consideration the entity expects to be entitled to receive in exchange for those goods or services.” Note: for many transactions, applying this principle will yield the same accounting as would applying the realization principle, but the conceptual underpinnings are very different. (T5-23) B. Key steps in applying the principle: 1. Identify a contract with a customer. © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-6 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e 2. 3. 4. 5. Identify the separate performance obligations in the contract. Determine the transaction price. Allocate the transaction price to the separate performance obligations. Recognize revenue when (or as) the entity satisfies each performance obligation. (T5-23) C. Step 1: Identify the contract. For purposes of applying revenue recognition criteria, a contract needs to have the following characteristics: (T5-24) 1. Commercial substance. The contract is expected to affect the seller’s future cash flows. 2. Approval. Each party to the contract has approved the contract and is committed to satisfying their respective obligations. 3. Rights. Each party’s rights are specified as to the transferred goods and services. 4. Payment terms. The terms and manner of payment are specified. 5. Performance. A contract does not exist if each party can terminate a wholly unperformed contract without penalty. A contract is wholly unperformed if no party has satisfied any of their obligations. D. Step 2: Identify separate performance obligations (T5-25) 1. A performance obligation is separate if it is distinct, which is the case if: i. the seller regularly sells the good or service separately, or ii. a buyer could use the good or service on its own or in combination with goods or services the buyer could obtain elsewhere. 2. A bundle of goods and services is treated as a single performance obligation if both of the following two criteria are met: i. The goods or services in the bundle are highly interrelated and the seller provides a significant service of integrating the goods or services into the combined item(s) delivered to a customer. ii. The bundle of goods or services is significantly modified or customized to fulfill the contract. iii. Example: many construction contracts. 3. If multiple distinct goods or services have the same pattern of transfer to the customer, the seller can treat them as a single performance obligation as a practical expediency. 4. Examples of separate performance obligations: (T5-26) i. Options to receive additional goods or services that provide a material right (but not a right of return). ii. Extended Warranties (but not warranties for latent defects). E. Step 3: Determine the transaction price (T5-27) 1. Include uncertain consideration, estimated as either i. most likely amount ii. probability weighted amount (T5-28) 2. Uncollectible accounts: i. Ability to estimate bad debts does not figure into whether to recognize revenue. ii. Treat bad debts as a contra-revenue (like sales returns) rather than as an expense. Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-7 3. Consider the time value of money if a contract has a significant financing component. (T5-29) i. Assume not significant if payment within one year. ii. Applies to prepayments (impute interest expense) and receivables (impute interest revenue). F. Step 4: Allocate the transaction price. (T5-30) 1. To separate performance obligations 2. Note: this approach is like current accounting for multiple-element arrangements. i. Allocate the transaction price to the separate performance obligations in proportion to the standalone selling price of the goods or services underlying those performance obligations. ii. Can use estimated selling prices. If can’t estimate, use the residual method. (T5-31) 3. If contract gets modified subsequently, reallocate transaction price to each separate performance obligation. G. Step 5: Recognize revenue when (or as) performance obligations are satisfied. (T5-32) 1. Basic idea: Satisfy performance obligations (and so recognize revenue) when transfer control to the buyer. 2. Satisfy over time if either: i. The seller is creating or enhancing an asset that the buyer controls as the service is performed, or ii. The seller is not creating an asset that that the buyer controls or that has alternative use to the seller, and either: 1. The customer receives and consumes a benefit as the seller performs. 2. Another seller would not need to re-perform the tasks performed to date if that other seller were to fulfill the remaining obligation. 3. The seller has the right to payment for performance even if the customer could cancel the contract. iii. “Integrating products and services” with interrelated risks and significant modification (as in long-term construction contracts) are viewed as a single performance obligation. iv. Amount recognized is limited to amount reasonably assured to be entitled to receive. PowerPoint Slides A PowerPoint presentation of the chapter is available at the textbook website. Teaching Transparency Masters The following can be reproduced on transparency film as they appear here, or you can use the disk version of this manual and first modify them to suit your particular needs or preferences. © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-8 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e DEFINITION AND REALIZATION PRINCIPLE According to the FASB, “Revenues are inflows or other enhancements of assets of an entity or settlements of its liabilities (or a combination of both) from delivering or producing goods, rendering services, or other activities that constitute the entity’s ongoing major or central operations.” In other words, revenue tracks the inflow of net assets that occurs when a business provides goods or services to its customers. The realization principle requires that two criteria be satisfied before revenue can be recognized: The earnings process is judged complete or virtually complete (the earnings process refers to the activity or activities performed by the company to generate revenue). There is reasonable certainty as to the collectibility of the asset to be received (usually cash). T5-1 Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-9 INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL REPORTING STANDARDS Revenue Recognition Concepts. IAS No. 18 governs most revenue recognition under IFRS. Similar to U.S. GAAP, it defines revenue as “the gross inflow of economic benefits during the period arising in the course of the ordinary activities of an entity when those inflows result in increases in equity, other than increases relating to contributions from equity participants.” IFRS allows revenue to be recognized when the following conditions have been satisfied: 1. The amount of revenue and costs associated with the transaction can be measured reliably, 2. It is probable that the economic benefits associated with the transaction will flow to the seller, 3. (for sales of goods) the seller has transferred to the buyer the risks and rewards of ownership, and doesn’t effectively manage or control the goods, 4. (for sales of services) the stage of completion can be measured reliably. Note: These general conditions typically will lead to revenue recognition at the same time and in the same amount as would occur under U.S. GAAP, but there are exceptions (e.g., multiple-deliverable contracts). More generally, IFRS has much less industry-specific guidance that does U.S. GAAP, leading to fewer exceptions to applying these revenue recognition conditions. T5-2 © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-10 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e IS THE SELLER A PRINCIPAL OR AN AGENT? Principal: Has primary responsibility for delivering a product or service, Typically is vulnerable to risks associated with delivering the product or service and collecting payment. If the company is a principal, the company should recognize as revenue the gross (total) amount received from a customer. Agent: Does not have primary responsibility for delivering a product or service, Is not vulnerable to risks associated with delivering the product or service and collecting payment. If the company is an agent, the company should recognize as revenue the net commission it receives for facilitating the sale. T5-3 Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-11 RELATION BETWEEN EARNINGS PROCESS AND REVENUE RECOGNITION METHODS Illustration 5-2 In most situations, the revenue recognition criteria are satisfied at the point of product delivery. T5-4 © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-12 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e REVENUE RECOGNITION Nature of the Revenue Usually Recognize Revenue for: Sale of a Product Sale of a Service Revenue Recognition Prior to Delivery, Because: Dependable estimates of progress are available. Each period during the earnings process (e.g., long-term construction contract) in proportion to its percentage of completion (percentage-of-completion method) Not applicable Dependable estimates of progress are not available. At the completion of the project (completed contract method) Not applicable Revenue Recognition at Delivery When product is delivered and title transfers As the service is provided or the key activity is performed • Payments are significantly uncertain When cash is collected (installment sales or cost recovery method) When cash is collected • Reliable estimates of product returns are unavailable When critical event occurs that reduces product return uncertainty Not applicable • The product sold is out on consignment When the consignee sells the product to the ultimate consumer Not applicable Revenue Recognition After Delivery, Because: Illustration 5-3 T5-5 Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-13 INSTALLMENT SALES METHOD The installment sales method recognizes gross profit by applying the gross profit percentage on the sale to the amount of cash actually received. On November 1, 2013, the Belmont Corporation, a real estate developer, sold a tract of land for $800,000. The sales agreement requires the customer to make four equal annual payments of $200,000 plus interest on each November 1, beginning November 1, 2013. The land cost $560,000 to develop. The company’s fiscal year ends on December 31. Illustration 5-1 Gross Profit Recognition Date Nov. 1, 2013 Nov. 1, 2014 Nov. 1, 2015 Nov. 1, 2016 Totals Cash Collected $200,000 200,000 200,000 200,000 $800,000 Cost Recovery ($560/$800=70%) $140,000 140,000 140,000 140,000 $560,000 Gross Profit ($240/$800=30%) $ 60,000 60,000 60,000 60,000 $240,000 T5-6 © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-14 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e INSTALLMENT SALES METHOD (continued) Journal Entries Nov. 1, 2013 To record installment sale Installment receivables ................................................... Inventory..................................................................... Deferred gross profit .................................................. 800,000 560,000 240,000 Nov. 1, 2013 To record cash collection from installment sale Cash ................................................................................ 200,000 Installment receivables ............................................... 200,000 To recognize gross profit from installment sale Deferred gross profit ...................................................... 60,000 Realized gross profit................................................... 60,000 T5-6 (continued) Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-15 COST RECOVERY METHOD The cost recovery method defers all gross profit recognition until cash equal to the cost of the item sold has been recovered. On November 1, 2013, the Belmont Corporation, a real estate developer, sold a tract of land for $800,000. The sales agreement requires the customer to make four equal annual payments of $200,000 plus interest on each November 1, beginning November 1, 2013. The land cost $560,000 to develop. The company’s fiscal year ends on December 31. Illustration 5-1 Gross Profit Recognition Date Nov. 1, 2013 Nov. 1, 2014 Nov. 1, 2015 Nov. 1, 2016 Totals Cash Collected $200,000 200,000 200,000 200,000 $800,000 Cost Recovery $200,000 200,000 160,000 -0$560,000 Gross Profit $ -0-040,000 200,000 $240,000 T5-7 © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-16 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e COST RECOVERY METHOD (continued) Journal Entries Nov. 1, 2013 To record installment sale Installment receivables ........................................ 800,000 Inventory .......................................................... 560,000 Deferred gross profit ........................................ 240,000 To record cash collection from installment sale Nov. 1, 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016 Cash ..................................................................... 200,000 Installment receivables .................................... 200,000 To recognize gross profit from installment sale Nov. 1, 2013 and 2014 No entry Nov. 1, 2015 Deferred gross profit ........................................... Realized gross profit ........................................ 40,000 40,000 Nov. 1, 2016 Deferred gross profit ........................................... 200,000 Realized gross profit ........................................ 200,000 T5-7 (continued) Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-17 RIGHT OF RETURN When the right of return exists, revenue cannot be recognized at the point of delivery unless the seller is able to make reliable estimates of future returns. In most retail situations, reliable estimates can be made and revenue and costs are recognized at point of delivery. Otherwise, revenue and cost recognition is delayed until the uncertainty is resolved. Disclosure of Revenue Recognition Policy — Intel Corporation Notes: Revenue Recognition We recognize net product revenue when the earnings process is complete, as evidenced by an agreement with the customer, transfer of title and acceptance, if applicable, as well as fixed pricing and probable collectibility. … Because of frequent sales price reductions and rapid technology obsolescence in the industry, we defer product revenue and related costs of sales from sales made to distributors under agreements allowing price protection and/or right of return until the distributors sell the merchandise. Illustration 5-8 T5-8 © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-18 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e COMPANIES ENGAGED IN LONG-TERM CONTRACTS Company Oracle Corp. Type of Industry or Product Computer software, license and consulting fees Lockheed Martin Corporation Aircraft, missiles and spacecraft Hewlett-Packard Information technology Northrop Grumman Newport News Shipbuilding Nortel Networks Corp Networking solutions and services to support the Internet SBA Communications Corp Telecommunications Layne Christensen Company Water supply services and geotechnical construction Kaufman & Broad Home Corp. Commercial and residential construction Raytheon Company Defense electronics Foster Wheeler Corp. Construction, petroleum and chemical facilities Halliburton Construction, energy services Allied Construction Products Corp. Large metal stamping presses Illustration 5-11 T5-9 Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-19 COMPLETED CONTRACT AND PERCENTAGE-OFCOMPLETION METHODS: AN EXAMPLE At the beginning of 2013, the Harding Construction Company received a contract to build an office building for $5 million. The project is estimated to take three years to complete. According to the contract, Harding will bill the buyer in installments over the construction period according to a prearranged schedule. Information related to the contract is as follows: 2013 Construction costs incurred during the year Construction costs incurred in prior years Cumulative construction costs Estimated costs to complete at end of year Total estimated and actual construction costs Billings made during the year Cash collections during year 2014 2015 $1,500,000 $1,000,000 $1,600,000 -01,500,000 1,500,000 2,500,000 2,500,000 4,100,000 2,250,000 1,500,000 -0- $3,750,000 $1,200,000 1,000,000 $4,000,000 $2,000,000 1,400,000 $4,100,000 $1,800,000 2,600,000 Illustration 5–12 T5-10 © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-20 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e JOURNAL ENTRIES 2013 BOTH METHODS: Construction in progress Cash, materials, etc. To record construction costs. 2014 2015 1,500,000 1,000,000 1,600,000 1,500,000 1,000,000 1,600,000 Accounts receivable Billings on construction contract To record progress billings. 1,200,000 2,000,000 1,800,000 1,200,000 2,000,000 1,800,000 Cash Accounts receivable To record cash collections. 1,000,000 1,400,000 2,600,000 1,000,000 1,400,000 2,600,000 COMPLETED CONTRACT: Construction in progress (gross profit) Cost of construction Revenue from long-term contracts To record gross profit. Billings on construction contract Construction in progress To close accounts. 900,000 4,100,000 5,000,000 5,000,000 5,000,000 PERCENTAGE-OF-COMPLETION: Construction in progress (gross profit) 500,000 125,000 275,000 Cost of construction 1,500,000 1,000,000 1,600,000 Revenue from long-term contracts 2,000,000 1,125,000 1,875,000 To record gross profit. Billings on construction contract Construction in progress To close accounts. 5,000,000 5,000,000 Illustrations 5-12a-c T5-11 Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-21 A COMPARISON OF THE TWO METHODS — INCOME RECOGNITION Gross profit recognized: 2013 2014 2015 Total gross profit Percentage-ofCompletion Completed Contract $500,000 125,000 275,000 $900,000 -0-0$900,000 $900,000 T5-12 © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-22 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e CALCULATING GROSS PROFIT UNDER THE PERCENTAGE-OF-COMPLETION METHOD 2013 2014 2015 Contract price $5,000,000 $5,000,000 $5,000,000 Construction costs: Construction costs incurred during the year Construction costs incurred in prior years Cumulative construction costs to date Estimated costs to complete at end of year Total estimated and actual construction costs $1,500,000 -0$1,500,000 2,250,000 $3,750,000 $1,000,000 1,500,000 $2,500,000 1,500,000 $4,000,000 $1,600,000 2,500,000 $4,100,000 -0$4,100,000 $1,250,000 $1,000,000 $900,000 X X X $1,500,000 $3,750,000 = 40% _________ $2,500,000 $4,000,000 = 62.5% __________ $4,100,000 $4,100,000 = 100% _________ $ 500,000 $ 625,000 $ 900,000 Total gross profit (estimated for 2013 & 2014, actual in 2015): Contract price minus total estimated and actual costs Multiplied by: Percentage-of-completion: Actual costs to date divided by the estimated total project cost Equals: Gross profit earned to date Minus: Gross profit recognized in prior periods - 0_________ (500,000) __________ (625,000) _________ $ 500,000 $ 125,000 $ 275,000 Equals: Gross profit recognized in current period Ilustration 5-12d, T5-13 Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-23 REVENUE AND COST OF CONSTRUCTION: PERCENTAGE-OF-COMPLETION METHOD 2013 Revenue recognized in 2013 ($5,000,000 x 40%) Cost of construction Gross profit 2014 Revenue recognized to date ($5,000,000 x 62.5%) Less: Revenue recognized in 2013 Revenue recognized in 2014 Cost of construction Gross profit 2013 Revenue recognized to date ($5,000,000 x 100%) Less: Revenue recognized in 2013 and 2014 Revenue recognized in 2015 Cost of construction Gross profit $2,000,000 1,500,000 $ 500,000 $3,125,000 (2,000,000) $1,125,000 1,000,000 $ 125,000 $5,000,000 (3,125,000) $1,875,000 1,600,000 $ 275,000 Illustration 5-12e T5-14 © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-24 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e BALANCE SHEET PRESENTATION Balance Sheet (End of year) 2013 Percentage-of-completion: Current assets: Accounts receivable Costs and profit ($2,000,000) in excess of billings ($1,200,000) Current liabilities: Billings ($3,200,000) in excess of costs and profit ($3,125,000) $ 200,000 800,000 Completed contract: Current assets: Accounts receivable Costs ($1,500,000) in excess of billings ($1,200,000) Current liabilities: Billings ($3,200,000) in excess of costs ($2,500,000) $ 200,000 300,000 2014 $800,000 75,000 $800,000 700,000 Illustration 5-12f T5-15 Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-25 LONG-TERM CONTRACT LOSSES An estimated loss on a long-term contract is fully recognized in the first period that the loss is anticipated, regardless of the revenue recognition method used. Construction costs incurred during the year Construction costs incurred in prior years Cumulative construction costs Estimated costs to complete at end of year Total estimated and actual construction costs 2013 2014 2015 $1,500,000 $1,260,000 $2,440,000 -01,500,000 $1,500,000 2,760,000 $2,760,000 5,200,000 2,250,000 2,340,000 -0- $3,750,000 $5,100,000 $5,200,000 Comparison of Periodic Gross Profit (Loss) Gross profit (loss) recognized: 2013 2014 2015 Total project loss Percentage-ofcompletion Completed Contract $500,000 (600,000) (100,000) $(200,000) -0$(100,000) (100,000) $(200,000) T5-16 © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-26 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL REPORTING STANDARDS Long-Term Construction Contracts. IAS No. 11 governs revenue recognition for long-term construction contracts. Like U.S. GAAP, IAS No. 11 requires use of percentage-of-completion accounting when estimates can be made precisely. Unlike U.S. GAAP, IAS No. 11 requires use of the cost recovery method rather than the completed contract method when estimates cannot be made precisely enough to allow percentage-of-completion accounting. Under the cost recovery method, contract costs are expensed as incurred, and an exactly offsetting amount of contract revenue is recognized, such that no gross profit is recognized until all costs have been incurred. Under both the cost recovery and completed contract methods, no gross profit is recognized until the contract is essentially completed, but revenue and construction costs will be recognized earlier under the cost recovery method than under the completed contract method. To see the difference, here is a version of Illustration 5-12B that compares cost and gross profit recognition under the two methods: COMPLETED CONTRACT: Construction in progress Cost of construction Revenue To record gross profit. COST RECOVERY: Construction in progress Cost of construction Revenue To record gross profit. 900,000 4,100,000 5,000,000 1,500,000 900,000 1,000,000 1,600,000 1,500,000 1,000,000 2,500,000 T5-17 Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-27 SOFTWARE AND OTHER MULTIPLE-ELEMENT ARRANGEMENTS If a software arrangement (sale) includes multiple elements, the revenue from the arrangement should be allocated to the various elements based on “VSOE” (vendor-specific objective evidence) of the individual elements. More generally, for multiple-element arrangements, revenue should be allocated to individual deliverables that qualify for separate revenue recognition. Otherwise, revenue is delayed until completion of later deliverables. Revenue is allocated according to the deliverables’ relative selling prices. These can be estimated if items aren’t sold separately. T5-18 © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-28 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e FRANCHISE SALES On March 31, 2013, the Red Hot Chicken Wing Corporation entered into a franchise agreement with Thomas Keller. In exchange for an initial franchise fee of $50,000, Red Hot will provide initial services to include the selection of a location, construction of the building, training of employees, and consulting services over several years. $10,000 is payable on March 31, 2013, with the remaining $40,000 payable in annual installments which include interest at an appropriate rate. In addition, the franchisee will pay continuing franchise fees of $1,000 per month for advertising and promotion provided by Red Hot, beginning immediately after the franchise begins operations. Thomas Keller opened his Red Hot franchise for business on September 30, 2013. Initial Franchise Fee March 31, 2013 To record franchise agreement and down payment Cash ................................................................................ 10,000 Note receivable ............................................................... 40,000 Unearned franchise fee revenue ................................. 50,000 Sept. 30, 2013 To recognize franchise fee revenue Unearned franchise fee revenue ..................................... Franchise fee revenue ................................................. 50,000 50,000 Continuing Franchise Fees To recognize continuing franchise fee revenue Cash (or accounts receivable) ........................................ 1,000 Service revenue .......................................................... 1,000 Illustration 5-16 T5-19 Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-29 ACTIVITY RATIOS Activity ratios measure a company's efficiency in managing its assets. Asset turnover ratio = Net sales Average total assets Receivables turnover ratio = Net sales Average accounts receivable (net) = 365 Receivables turnover ratio = Cost of goods sold Average Inventory Average collection period Inventory turnover ratio Average days in inventory = 365 Inventory turnover ratio T5-20 © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-30 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e PROFITABILITY RATIOS Profitability ratios assist in evaluating various aspects of a company's profit-making activities. Profit margin on sales = Net income Net sales Return on assets = Net income Average total assets Return on shareholders' equity = Net income Average shareholders' equity T5-21 Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-31 DUPONT FRAMEWORK The DuPont Framework helps identify how profitability, activity, and financial leverage trade off to determine return to shareholders: Return on equity Net income Avg. total equity = Profit margin X Net income = Total sales X Asset turnover Total sales Avg. total assets X Equity multiplier Avg. total assets X Avg. total equity Because profit margin and asset turnover combine to equal return on assets, the DuPont framework can also be written as: Return on equity Net income Avg. total equity = = Return on assets Equity multiplier X Net income Avg. total assets Avg. total assets X Avg. total equity T5-22 © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-32 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e THE NEW REVENUE RECOGNITION FRAMEWORK CORE REVENUE RECOGNITION PRINCIPLE An entity shall recognize revenue to depict the transfer of goods or services to customers in an amount that reflects the consideration the entity expects to be entitled to receive, in exchange for those goods or services. KEY STEPS IN APPLYING THE PRINCIPLE 1) Identify a contract with a customer. 2) Identify the separate performance obligations in the contract. 3) Determine the transaction price. 4) Allocate the transaction price to the separate performance obligations. 5) Recognize revenue when (or as) the entity satisfies each performance obligation. T5-23 Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-33 STEP 1: IDENTIFY THE CONTRACT For purposes of applying revenue recognition criteria, a contract needs to have the following characteristics: Commercial substance. The contract is expected to affect the seller’s future cash flows. Approval. Each party to the contract has approved the contract and is committed to satisfying their respective obligations. Rights. Each party’s rights are specified with regard to the goods or services to be transferred. Payment terms. The terms and manner of payment are specified. Performance. A contract does not exist if each party can terminate a wholly unperformed contract without penalty. A contract is wholly unperformed if no party has satisfied any of their obligations. T5-24 © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-34 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e STEP 2: IDENTIFY SEPARATE PERFORMANCE OBLIGATIONS A performance obligation is accounted for as separate if it is distinct, which is the case if either: The seller regularly sells the good or service separately, or A buyer could use the good or service on its own or in combination with goods or services the buyer could obtain elsewhere. A bundle of goods and services is treated as a single performance obligation if both of the following two criteria are met: 1. The goods or services in the bundle are highly interrelated and the seller provides a significant service of integrating the goods or services into a combined item(s) for the customer. 2. The bundle of goods or services is significantly modified or customized to fulfill the contract. Example: many construction contracts. If multiple distinct goods or services have the same pattern of transfer to the customer, the seller can treat them as a single performance obligation as a practical expediency. Examples of separate performance obligations: Options to receive additional goods or services that provide a material right (but not a right of return). Extended Warranties (but not warranties for latent defects). T5-25 Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-35 STEP 2 EXAMPLE TrueTech Industries manufactures the Tri-Box System, a multiplayer gaming system allowing players to compete with each other over the Internet. The Tri-Box System has a wholesale price of $270 that includes the physical Tri-Box module as well as a one-year subscription to the Tri-Net of Internet-based games and other applications. TrueTech sells one-year subscriptions to the Tri-Net separately for $50 to owners of Tri-Box modules as well as owners of other gaming systems. TrueTech does not sell a Tri-Box module without the initial one-year Tri-Net subscription, but estimates that it would charge $250 per module if modules were sold alone. CompStores purchases 1,000 Tri-Box Systems at the normal wholesale price of $270. What separate performance obligations exist in the TrueTech contract? Illustration 5-21 T5-26 © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-36 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e STEP 2 EXAMPLE (continued) What separate performance obligations exist in the TrueTech contract with CompStores? Although TrueTech does not sell the module separately, the module would have a function to the buyer in combination with games and subscription services the buyer could obtain elsewhere. The Tri-Net subscription is sold separately. Therefore, the contract has two separate performance obligations: (1) delivery of Tri-Box modules and (2) fulfillment of Tri-Net subscriptions via access to the Tri-Net network over a one-year period. Illustration 5-21 T5-26 (continued) Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-37 STEP 3: DETERMINE THE TRANSACTION PRICE Include uncertain consideration, estimated as either most likely amount probability weighted amount Uncollectible accounts: Ability to estimate bad debts does not figure into whether to recognize revenue. Treat bad debts as a contra-revenue (like sales returns) rather than as an expense. Consider the time value of money if a contract has a significant financing component. Assume not significant if payment within one year. Applies to prepayments (impute interest expense) and receivables (impute interest revenue). T5-27 © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-38 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e STEP 3 EXAMPLE: UNCERTAIN CONSIDERATION TrueTech enters into a contract with ProSport Gaming to add ProSport’s online games to the Tri-Net network. ProSport will pay TrueTech an up-front $300,000 fixed fee for six months of featured access, as well as a $200,000 bonus if Tri-Net users access ProSport products for at least 15,000 hours during the six month period. TrueTech estimates a 75% chance that it will achieve the usage target and earn the $200,000 bonus. TrueTech would make the following entry at contract inception to record receipt of the cash: Cash 300,000 Unearned Revenue 300,000 Two possibilities to estimate the uncertain consideration: Probability-Weighted Amount A probability-weighted transaction price would be calculated as follows: Possible Amounts $500,000 ($300,000 + 200,000) Prob. X 75% = $300,000 ($300,000 + 0) X 25% = Expected contract price at inception Expected Amounts $375,000 75,000 $450,000 Most Likely Amount The most likely amount of bonus is $200,000, so a transaction price based on the most likely amount would be $300,000 + 200,000, or $500,000. Illustration 5-22 T5-28 Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-39 STEP 3 EXAMPLE: UNCERTAIN CONSIDERATION (continued) In this case, it is likely that TrueTech would use the estimate based on the most likely amount, $500,000, because only two outcomes are possible, and it is likely that the bonus will be received. In each successive month, TrueTech would recognize one month’s revenue based on a total transaction price of $500,000, reducing unearned revenue and recognizing bonus receivable: Unearned revenue($300,000 ÷ 6 months) Bonus receivable (to balance) Revenue ($500,000 ÷ 6 months) 50,000 33,333 83,333 After six months, TrueTech’s Unearned revenue account would be reduced to a zero balance, and the Bonus receivable would have a balance of $200,000 ($33,333 x 6). At that point TrueTech would know if the usage of ProSport products had reached the bonus threshold and would make one of the following two journal entries: If TrueTech receives the bonus: Cash If TrueTech does not receive the bonus: 200,000 Revenue 200,000 Bonus receivable 200,000 Bonus receivable 200,000 T5-28 (continued) © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-40 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e STEP 3 EXAMPLE: TIME VALUE OF MONEY On January 1, 2013, TrueTech enters into a contract with GameStop Stores to deliver four Tri-Box modules that have a fair value of $1,000. Prepayment Case: GameStop pays TrueTech $907 on January 1, 2013 and TrueTech agrees to deliver the modules on December 31, 2014. GameStop pays significantly in advance of delivery, such that TrueTech is viewed as borrowing money from GameStop and TrueTech incurs interest expense. Receivable Case: TrueTech delivers the modules on January 1, 2013 and GameStop agrees to pay TrueTech $1,000 on December 31, 2014. TrueTech delivers the modules significantly in advance of payment, such that TrueTech is viewed as loaning money to GameStop and TrueTech earns interest revenue. The fiscal year-end for both companies is December 31. The time value of money in both cases is 5%. Illustration 5-23 T5-29 Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-41 STEP 3 EXAMPLE: TIME VALUE OF MONEY (continued) The following table compares TrueTech’s accounting for the contract between the two cases (ignoring the entry for cost of goods sold): Prepayment (payment before delivery) January 1, 2013 When prepayment occurs: Cash Unearned revenue Receivable (payment after delivery) 907 December 31, 2013: Accrual of year 1 interest expense: Interest expense ($907 x 5%) 45 Unearned revenue 907 45 December 31, 2014 When subsequent delivery occurs: Interest expense ($952 x 5%) 48 Unearned revenue 952 Revenue 1,000 January 1, 2013 When delivery occurs: Accounts receivable Revenue 1,000 1,000 December 31, 2013: Accrual of year 1 interest revenue: Accounts receivable 50 Interest revenue ($1000 x 5%) 50 December 31, 2014 When subsequent payment occurs: Cash 1,103 Interest revenue ($1050 x 5%) 53 Accounts receivable 1,050 T5-29 (continued) © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-42 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e STEP 4: ALLOCATE THE TRANSACTION PRICE TO SEPARATE PERFORMANCE OBLIGATIONS Note: this approach is like current accounting for multipleelement arrangements. Allocate the transaction price to the separate performance obligations in proportion to the standalone selling price of the goods or services underlying those performance obligations. Can use estimated selling prices. If contract gets modified subsequently, reallocate transaction price to each separate performance obligation. T5-30 Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-43 STEP 4 EXAMPLE Recall the initial data for the TrueTech example from Illustration 5-20: The Tri-Box System has a wholesale price of $270, which includes the physical Tri-Box console as well as a one-year subscription to the TriNet of Internet-based games and other applications. Owners of Tri-Box modules as well as other game consoles can purchase one-year subscriptions to the Tri-Net from TrueTech for $50. TrueTech does not sell a Tri-Box module without the initial one-year Tri-Net subscription, but estimates that it would charge $250 per unit if it chose to do so. CompStores orders 1,000 Tri-Boxes at the normal wholesale price of $270. Because the standalone price of the Tri-Box module ($250) represents 5/6 of the total fair values ($250 ÷ [$250 + 50]), and the Tri-Net subscription comprises 1/6 of the total ($50 ÷ [$250 + 50]), we allocate 5/6 of the transaction price to the Tri-Boxes and 1/6 of the transaction price to the TriNet subscriptions. Accordingly, TrueTech would recognize the following journal entry (ignoring any entry to record the reduction in inventory and the corresponding cost of goods sold): Accounts receivable Revenue ($270,000 x 5/6) Unearned revenue ($270,000 x 1/6) 270,000 225,000 45,000 TrueTech then converts the unearned revenue to revenue over the one-year term of the Tri-Net subscription as that revenue is earned. Illustration 5-24 T5-31 © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-44 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e STEP 4 EXAMPLE (continued) Assume the same facts as Illustration 5-24, except that there is no basis on which to estimate the value of the one-year Tri-Net subscription. In that case, the value of the subscription would be estimated using the residual method as follows: Total price of Tri-Box with Tri-Net subscription Estimated price of Tri-Box sold without subscription Estimated price of Tri-Net subscription: $270 250 $ 20 Based on these relative standalone selling prices, if CompStores orders 1000 Tri-Boxes at the normal wholesale price of $270, TrueTech would recognize the following journal entry (ignoring any entry to record the reduction in inventory and corresponding cost of goods sold): Accounts receivable Revenue (1,000 x $250) Unearned revenue $1,000 x $20) 270,000 250,000 20,000 TrueTech would convert the unearned revenue to revenue over the oneyear term of the Tri-Net subscription. Illustration 5-25 T5-31 (continued) Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-45 STEP 5: RECOGNIZE REVENUE AS PERFORMANCE OBLIGATIONS ARE SATISFIED In general: Satisfy a performance obligation, and so recognize revenue, when transfer control to the buyer. Satisfy over time if either: The seller is creating or enhancing an asset that the buyer controls as the service is performed, or The seller is not creating an asset that that the buyer controls or that has alternative use to the seller, and either: o The buyer simultaneously receives and consumes a benefit as the seller performs the service. o Another seller would not need to re-perform the tasks performed to date if that other seller were to fulfill the remaining obligation. o The seller has the right to payment for performance even if the buyer could cancel the contract. “Integrating products and services” with interrelated risks and significant modification (as in long-term construction contracts) are viewed as a performance obligation. Amount recognized is limited to amount reasonably assured to be entitled to receive. If don’t satisfy over time, satisfy at a point in time, when transfer control. T5-32 © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-46 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e Suggestions for Class Activities 1. Real World Scenario The following is an excerpt from an article that appeared in the August 25, 2002 edition of The Seattle Times: When Cutter & Buck revealed two weeks ago that it padded sales figures in 2000 by recording $5.8 million in shipments that were mostly returned, the news came as a surprise to many investors. But it wasn’t the first time the Seattle sportswear retailer’s shipping and accounting practices have been called into question. Shortly before co-founder Joey Rodolfo left in 1997, he accused the company of shipping orders months before customers were expecting them, a method of prematurely booking sales. Some customers and former employees say early shipments persisted for years after Rodolfo raised the issue. And late last week, Chief Executive Fran Conley said an internal investigation has found that early shipments were “more extensive than I had known” and may force the company to further restate sales figures. Shipping and booking orders ahead of schedule to meet short-term sales goals — a practice sometimes called channel stuffing — is not, by definition, illegal. But by essentially borrowing from future sales to claim bigger current sales and profit, it can be used to boost a company’s bottom line and create a misleading appearance of growth for investors. Suggestions: This article provides a good way to introduce the topic of channel stuffing. When a company stuffs the channel, it ships inventory ahead of schedule filling its distribution channels with more product than is needed. Since companies often record sales as soon as they ship products, channel stuffing can make it appear that business is booming. Is this practice legal? Is it an acceptable practice according to GAAP? Is it an ethical practice? Points to note: Channel stuffing is not an uncommon practice. There are many examples you can find for your students. A text case references the Sunbeam incident that occurred in the late 90s. More recent examples include Microsoft, Novell, Network Associates, and AOL. GAAP do not address channel stuffing specifically. The key is whether or not the practice leads to excessive future sales returns that are not adequately provided for by the seller. There may be an issue with respect to the legality of the practice if it can be shown that the practice resulted in misleading information to the investing public. And there are ethical dimensions to the practice as well. Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-47 2. Research Activity Probably most of your students have purchased merchandise via the Internet. You can buy the products of many companies on line. Some of these companies, such as Amazon.com, often act merely as intermediaries between the manufacturer and the consumer. Revenue recognition for this type of transaction has been controversial. If Amazon sells something to a customer for $100 that costs $80, the profit on the transaction is clearly $20. But should Amazon recognize $100 in revenue and $80 in cost of goods sold (the gross method), or should it recognize only the $20 in gross profit (the net method)? Suggestions: Discuss with your class the implications of one reporting method versus the other. Why should it make a difference? What factors might dictate whether or not Amazon should recognize the transaction gross versus net? Have them access Amazon’s most recent financial statements using Edgar (at http://www.sec.gov/edgar.shtml). Or, you can show them Amazon’s disclosure note and discuss the contents of the note. The following is a portion of the company’s revenue recognition disclosure note that appeared in its 2010 financial statements: We recognize revenue from product sales or services rendered when the following four criteria are met: persuasive evidence of an arrangement exists, delivery has occurred or services have been rendered, the selling price is fixed or determinable, and collectability is reasonably assured. Revenue arrangements with multiple deliverables are divided into separate units and revenue is allocated using estimated selling prices if we do not have vendorspecific objective evidence or third-party evidence of the selling prices of the deliverables. …. We evaluate whether it is appropriate to record the gross amount of product sales and related costs or the net amount earned as commissions. Generally, when we are primarily obligated in a transaction, are subject to inventory risk, have latitude in establishing prices and selecting suppliers, or have several but not all of these indicators, revenue is recorded at the gross sales price. If we are not primarily obligated, and do not have latitude in establishing prices, amounts earned are determined using a fixed percentage, a fixed-payment schedule, or a combination of the two, we generally record the net amounts as commissions earned. © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-48 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e 3. Google Analysis Have students, individually or in groups, go to the most recent Google annual report using Edgar which can be located at: http://www.sec.gov/edgar.shtml. Ask them to: 1. Compute the receivables turnover ratio, the profit margin on sales, the return on assets ratio, and the return on shareholders' equity ratio for the most three years. Are there any discernible trends? How might they be interpreted? 2. Read the "Revenues" section of "Management's Discussion and Analysis of Results of Operations and Financial Condition." Has there been any significant shift over the last three years in the company's service revenue mix? 3. Use Edgar to locate the most recent annual report information for Yahoo, Google’s competitor. Using the most recent annual report information for both companies, compare the receivables turnover ratio, the profit margin on sales, the return on assets ratio, and the return on shareholders' equity ratio. Are there any differences in the way the companies recognize revenue? 4. Note: another peer comparison of this nature is Federal Express vs. United Parcel Service. 4. Professional Skills Development Activities The following are suggested assignments from the end-of-chapter material that will help your students develop their communication, research, analysis and judgment skills. Communication Skills. In addition to Communication Case 5-15, Judgment Case 5-14 can be adapted to ask students to choose one of the two alternatives and write a memo supporting their position. Communication Case 5-5, Judgment Case 5-4, and IFRS Case 5-17 do well as group assignments. Research Case 5-6 and Ethics Case 5-8 create good class discussions. Problem 512 and Analysis Case 5-21 are suitable for student presentation(s). Research Skills. In their careers, our graduates will be required to locate and extract relevant information from available resource material to determine the correct accounting practice, perhaps identifying the appropriate authoritative literature to support a decision. Research Cases 5-11, 5-12 and 5-13 and Real World Cast 5-21 provide an excellent opportunity to help students develop this skill, as does the Air France-KLM case. Analysis Skills. The “Broaden Your Perspective” section includes Analysis Cases that direct students to gather, assemble, organize, process, or interpret data to provide options for making business and investment decisions. In addition to Analysis Case 5-21; Exercises 5-23, 5-24, 525, and 5-26; Problems 5-11, 5-12, 5-13, and 5-14, and Judgment Case 5-17 also provide opportunities to develop and sharpen analytical skills. Judgment Skills. The “Broaden Your Perspective” section includes Judgment Cases that require students to critically analyze issues to apply concepts learned to business situations in order to Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-49 evaluate options for decision-making and provide an appropriate conclusion. In addition to Judgment Cases 5-2, 5-3, 5-4, 5-9, 5-10, 5-13, 5-14, and 5-22 Real World Case 5-1 also requires students to exercise judgment. 5. Ethical Dilemma The chapter contains the following ethical dilemma: ETHICAL DILEMMA The Precision Parts Corporation manufactures automobile parts. The company has reported a profit every year since the company’s inception in 1977. Management prides itself on this accomplishment and believes one important contributing factor is the company’s incentive plan that rewards top management a bonus equal to a percentage of operating income if the operating income goal for the year is achieved. However, 2013 has been a tough year, and prospects for attaining the income goal for the year are bleak. Tony Smith, the company’s chief financial officer, has determined a way to increase December sales by an amount sufficient to boost operating income over the goal for the year and earn bonuses for all top management. A reputable customer ordered $120,000 of parts to be shipped on January 15, 2014. Tony told the rest of top management “I know we can get that order ready by December 31 even though it will require some production line overtime. We can then just leave the order on the loading dock until shipment. I see nothing wrong with recognizing the sale in 2013, since the parts will have been manufactured and we do have a firm order from a reputable customer.” The company’s normal procedure is to ship goods f.o.b. destination and to recognize sales revenue when the customer receives the parts. You may wish to discuss this in class. If so, discussion should include these elements. Step 1—The Facts: Precision Parts Corporation has reported profits since its inception and given top management bonuses when the operating income goal is achieved. In 2013, however, the company does not expect to achieve its profit goal. Tony Smith, the CFO, wants to record a sale in 2013 that will not be shipped until January 2014, so that management will receive bonuses for achieving the profit goal. The CFO is attempting to manipulate the recognition of revenue. The company's normal procedure is to recognize sales revenue when goods are shipped f.o.b. destination. Although sales revenue may be recognized when production ends if certainty of collection exists, nothing in the case indicates that there is reasonable certainty as to the collectibility of the revenue at the end of production. © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-50 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e Step 2—The Ethical Issue and the Stakeholders: The ethical issue or dilemma is whether Tony Smith's obligation to top management to show a profit is greater than his obligation to provide information that is not misleading to users of financial statements. Stakeholders include Tony Smith, CFO, other corporate managers, auditors, present and future creditors, and current and future investors. Step 3—Values: Values include competence, honesty, integrity, objectivity, loyalty to the company, and responsibility to users of financial statements. Step 4—Alternatives: 1. Record the parts sales revenue in 2013. 2. Record the parts sales revenue in 2014, when the goods are shipped. Step 5—Evaluation of Alternatives in Terms of Values: 1. Alternative 1 illustrates loyalty to the company and other top managers. 2. Alternative 2 exhibits the values of competence, honesty, integrity, objectivity, and responsibility to users of the financial statements. Step 6—Consequences: Alternative 1 Positive consequences: Tony would enable other top managers to receive bonuses and permit the company to meet their operating income goal. Negative consequences: Users of the financial statements would be misinformed. Users of financial statements may sue the company upon learning the truth if the amount of revenue is material and affects their financial decisions. Auditors may refuse to give a positive opinion on the fair presentation of the financial statements. Tony may lose the respect of the rest of top management and his job. Alternative 2 Positive consequences: Users of financial statements would receive more relevant and reliable reported revenue. Tony would maintain his integrity. He may receive praise for being honest and keep his job. Negative consequences: Tony may incur the disfavor of the rest of top management for not enabling others to receive a bonus. He may lose the trust of other managers and lose his job. Step 7—Decision: Student(s) must decide their course of action. Instructors Resource Manual © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-51 Assignment Chart Questions 5-1 5-2 5-3 5-4 5-5 5-6 5-7 5-8 5-9 5-10 5-11 5-12 5-13 5-14 5-15 5-16 5-17 5-18 5-19 5-20 5-21 Brief Exercises 5-1 5-2 5-3 5-4 5-5 5-6 5-7 5-8 5-9 5-10 5-11 5-12 5-13 5-14 5-15 5-16 5-17 5-18 © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-52 Learning Objective(s) 1 1 2 3 3 3 4 1 5 5 5,8 5 5 6 6,8 6 7 7 7 1 8 Est. time Topic (min.) Revenue recognition criteria 5 Revenue recognition at point of delivery 5 Principal or agent Installment sales 5 Installment sales and cost recovery methods 5 Deferred gross profit—installment sales method 5 Right of return 5 Consignment sale 5 Service revenue 5 Percentage-of-completion and completed contract methods 5 IFRS; cost recovery method for long-term contracts 5 Billings on construction contract 5 Estimated loss on construction project 5 Software sales 5 IFRS; multiple-deliverable arrangements 5 Franchise fee revenue recognition 5 Activity ratios 5 Profitability ratios 5 DuPont framework 5 Interim reports [based on Appendix] 5 Interim reports [based on Appendix] 5 Learning Objective(s) 1 2 3 3 3 4 5 5 5 5,8 5 6 6,8 6 7 7 7 7 Est. time (min.) 5 10 10 10 10 5 10 10 5 10 10 10 10 5 5 10 10 10 Topic Point of delivery recognition Principal or agent Installment sales method Cost recovery method Installment sales method Right of return Percentage-of-completion method; profit recognition Percentage-of-completion method; balance sheet Completed contract method IFRS; cost recovery method for long-term contracts Long-term contract accounting; loss on entire project Multiple-deliverable contracts IFRS; multiple deliverable contracts Franchise sales Turnover ratios Profitability ratios DuPont framework Inventory turnover ratio Intermediate Accounting, 7/e 5-1 5-2 5-3 5-4 5-5 Learning Objective(s) 1 2 3 3 3 5-6 1,3 5-7 3 5-8 5-9 5-10 3 1,3 3,4,5 5-11 5 5-12 5,8 5-13 5 5-14 5 5-15 5 5-16 5-17 5-18 5-19 5-20 5-21 5-22 5-23 5-24 5-25 5-26 5 5 6 6 6,8 6 2,4,5,6,7 7 7 7 7 5-27 1 5-28 1 5-29 1 5-30 8 Exercises Instructors Resource Manual Est. time (min.) Service revenue 15 Principal or agent 10 Installment sales method 20 Installment sales method; journal entries 15 Installment sales; alternative recognition methods 15 Journal entries; point of delivery, installment sales, and cost 25 recovery methods Installment sales and cost recovery methods; solve for 10 unknowns Installment sales method and repossession. 20 Real estate sales; gain recognition 15 Percentage-of-completion, installment, and cost-recovery methods, right of return, codification Percentage-of-completion and completed contract methods 20 IFRS; long-term contract; percentage of completion and 30 completed contract methods Percentage-of-completion method; loss projected on entire 30 project Completed contract method; loss projected on entire 20 project Income (loss) recognition; percentage-of-completion and 50 completed contract methods compared Percentage-of-completion method; solve for unknowns 25 Percentage-of-completion, codification 10 Revenue recognition; software 10 Revenue recognition; Multiple-deliverable contracts 15 IFRS; multiple-deliverable contracts 15 Revenue recognition; franchise sales 10 Concepts; terminology 15 Inventory turnover; calculation and evaluation 10 Evaluating efficiency of asset management 10 Profitability ratios 10 DuPont framework 10 Interim financial statements; income tax expense [based on 10 Appendix] Interim reporting; recognizing expenses [based on 10 Appendix] Interim financial statements; reporting expenses [based on 10 Appendix] Interim financial statements; reporting expenses under IFRS [based on Appendix] Topic © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-53 CPA Review Questions Learning Objective(s) 1 3 3 5 5 5 1,8 5,8 6,8 1,8 5-1 5-2 5-3 5-4 5-5 5-6 5-7 5-8 5-9 5-10 Topic Revenue recognition upon delivery Installment sales method Installment sales method Percentage-of-completion method Percentage-of-completion method Percentage-of-completion method Revenue recognition criteria under IFRS Percentage-of-completion method under IFRS Multiple-element contracts under IFRS Interim financial statements under IFRS Est. time (min.) 3 3 3 2 3 3 3 3 3 3 CMA Review Questions Learning Objective(s) Topic Est. time (min.) 5-1 5-2 5-3 1 5 5 Revenue recognition upon delivery and bad debts Percentage-of-completion method Percentage-of-completion method 3 3 3 Problems 5-1 5-2 5-3 5-4 5-5 5-6 5-7 5-8 5-9 5-10 5-11 5-12 5-13 Learning Objective(s) 2 2 2 2 5 5 5,8 5 5 2,6 7 7 7 5-14 7 5-15 1 Est. time Topic (min.) Income statement presentation; installment sales method 25 [Chapters 4 and 5] Installment sales and cost recovery methods 30 Installment sales; alternative recognition methods 30 Installment sales and cost recovery methods, multiple years 30 Percentage-of-completion method 45 Completed contract method 40 IFRS; Construction accounting 40 Construction accounting; loss projected on entire project 25 Percentage-of-completion and completed contract methods 45 Franchise sales, installment sales method 25 Calculating activity and profitability ratios 20 Use of ratios to compare two companies in the same 40 industry; Johnson and Johnson, Pfizer Creating a balance sheet from ratios; chapters 3 and 5 50 Use of ratios to compare two companies in the same 40 industry; chapters 3 and 5 Interim financial reporting [based on Appendix] 15 Star Problems © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-54 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e Cases Real World Case 5-1 Judgment Case 5-2 Judgment Case 5-3 Judgment Case 5-4 Communication Case 5-5 Research Case 5-6 Research Case 5-7 Ethics Case 5-8 Judgment Case 5-9 Judgment Case 5-10 Research Case 5-11 Research Case 5-12 Judgment Case 5-13 Judgment Case 5-14 Communication Case 5-15 IFRS Case 5-16 Learning Objective(s) 1 1 1 1 1 5 1 1 1,2 1 4 1 1,5 5 5 1,5,8 IFRS Case 5-17 Trueblood Accounting Case 5-18 5,8 6 Trueblood Accounting Case 5-19 Real World Case 5-20 Real World Case 5-21 Analysis Case 5-22 Judgment Case 5-23 Integrating Case 5-24 6 6 2 7 7 7 Air France-KLM Case 8 Instructors Resource Manual Est. time Topic (min.) Revenue recognition and earnings management; Sunbeam 20 Revenue recognition 15 Revenue recognition for initial and monthly fees 15 Revenue recognition; trade-ins 20 Revenue recognition 20 Long-term contract accounting 45 Earnings management techniques for revenues 30 Revenue recognition 15 Revenue recognition ; installment sales 20 Revenue recognition; SAB 101 questions, codification 20 45 Revenue recognition; right of return; Hewlett Packard, Advanced Micro Devices, codification Earnings management: gross vs. net and EITF 99-19; 30 Google, codification Revenue recognition, service sales 15 Revenue recognition; long-term construction contracts 15 Percentage-of-completion and completed contract methods 50 IFRS; Comparison of revenue recognition in Sweden and 15 the U.S.A.; Vodafone IFRS; Construction accounting 30 Revenue recognition for a multiple-element software 60 contract Revenue recognition for multiple-element contracts 45 50 Revenue recognition; franchise sales; Jack in the Box Principal or agent; Orbitz and priceline.com 60 Evaluating profitability and asset management 60 Relationships among ratios, chapters 3 and 5 30 Using ratios, chapters 3 and 5 45 IFRS, deferred revenue, multiple-element contracts; Air France-KLM 45 © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-55 Supplement Est. time Questions 5-22 5-23 5-24 5-25 5-26 5-27 Topic Five steps to recognizing revenue Characteristics of separate performance obligations Options as separate performance obligations Allocating transaction price Satisfying performance obligation for a good Continuous revenue recognition Brief Exercises 5-19 5-20 5-21 5-22 5-23 5-24 5-25 (min.) 5 5 5 5 5 5 Est. time Topic (min.) Difinition of a contract Separate performance obligations Separate performance obligations Uncertain consideration Allocating transaction price Long-term contracts Time value of money 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 Est. time Exercises 5-31 5-32 5-33 5-34 5-35 5-36 5-37 5-38 Topic Options Separate performance obligation, option Separate performance obligation, licensing Uncertain consideration Uncertain consideration Satifying performance obligation Satisfying performance obligation Time value of money (min.) 15 15 15 15 15 15 10 15 Est. time Problems Topic 5-16 Upfront fees, separate performance obligations 5-17 Satisfying performance obligations 5-18 Uncertain consideration 5-19 Uncertain consideration Star Problems © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2013 5-56 (min.) 45 45 30 45 Intermediate Accounting, 7/e