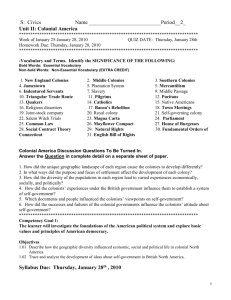

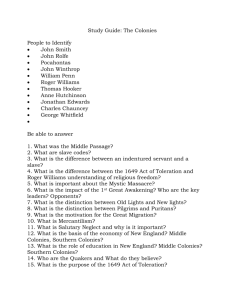

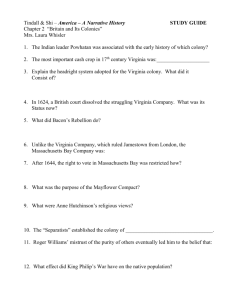

Early Colonization Timeline 1430 Portuguese start voyages down

advertisement