Acute Abdomen - Fraser Health Authority

advertisement

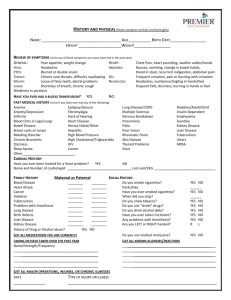

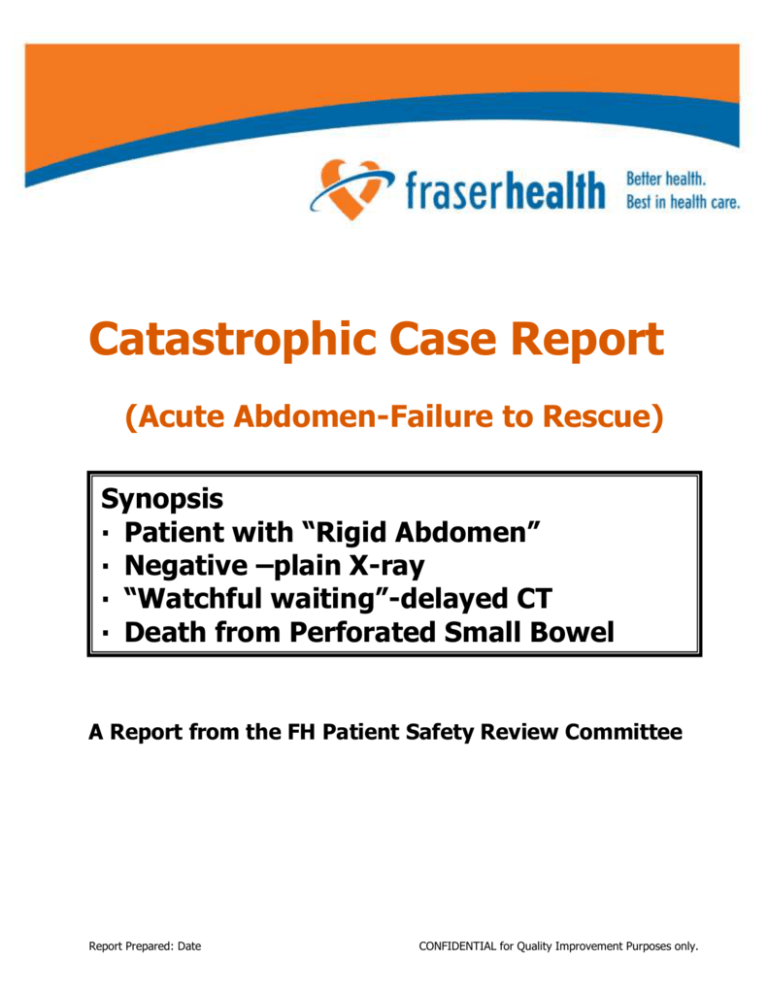

Catastrophic Case Report (Acute Abdomen-Failure to Rescue) Synopsis ∙ Patient with “Rigid Abdomen” ∙ Negative –plain X-ray ∙ “Watchful waiting”-delayed CT ∙ Death from Perforated Small Bowel 8 month old child: ∙ Temp 40.3°C . . . HR 199 A∙Report from the FH Patient Safety Review Committee Looks well ∙ No Treatment, discharged ∙ Sudden Death 48 hours later Report Prepared: Date CONFIDENTIAL for Quality Improvement Purposes only. ACUTE ABDOMEN-PERFORATED VISCUS-THE ROLE OF CT AND ANTIBIOTIC CHOICE Executive Summary-Briefing Case Summary A patient was sent to the ER with presumptive diagnosis of “Perforated Viscus.” The patient had a board-like abdomen and elevated WBC with severe pain. Abdominal plain films were normal and were repeated after the gastric insufflation of 500cc air by an NG tube. A second set of films was also negative. The patient was admitted overnight for observation and prescribed Morphine, Cefazolin and Metronidazole. During the night there was progressive development of sepsis. The patient had a CT scan of the abdomen the following morning. This demonstrated a small amount of free intraperitoneal air and thickening of the mid small bowel wall. The patient was taken to the OR and died immediately after resection of a perforated segment of small bowel. Pathology revealed a small bowel lymphoma with perforation. Cause of death was sepsis secondary to bowel perforation and peritonitis. Background The ‘Acute abdomen’ is a general term applied to patients presenting with severe, acute abdominal pain. In these cases, the examining physician searches for the etiology with some urgency as they often require surgical intervention. The clinician "makes a serious and thorough attempt at diagnosis by means of the history, physical examination and ancillary diagnostics." Two concerns stood out in the review. Why was an abdominal CT not performed when plain films were negative? Why was Cefazolin/Flagyl chosen as antibiotic coverage? This patient presented with a “Rigid Abdomen” and early surgical intervention was likely the preferred approach. Diagnostic Laparotomy is a valuable tool. In Surgical practice delays for diagnostic work ups should be weighed against the risk of catastrophic septic complications in the Acute abdomen. CT SCAN IN ACUTE ABDOMEN CT has become the front line diagnostic tool to aid history and physical exam in the evaluation the acute abdomen. Despite good clinical skills, there are times and circumstances where CT is essential in the disposition and management of a patient. This is especially true when the clinical presentation is confusing. In some cases of acute appendicitis or diverticulitis with abscess formation, the accurate diagnosis of the problem can lead to non-operative image-guided, percutaneous therapy. In free perforations (as in this case), ischemic bowel or a closed loop small bowel obstruction, the rapid diagnosis by CT may facilitate surgery. Plain abdominal films have limited utility (may reveal ileus, bowel obstruction, free air, ascites or interstitial gas. CT has supplanted plain films in the Acute Abdomen. The advantages of CT include versatility and a wide margin of error. It provides a global survey of the abdomen, presents useful surgical anatomy and has high sensitivity in detecting pneumoperitoneum CONFIDENTIAL for Quality Improvement Purposes only. Page A ANTIBIOTIC CHOICES FOR INTRA-ABDOMINAL INFECTIONS (possible perforated viscus) This patient was given a standard cocktail of Cefazolin and Flagyl for possible perforated viscus. A random survey of Emergency Physicians, Surgeons and Internists revealed a variable approach to empiric treatment of “Acute Abdomen”. A review of the literature and consultation with local experts has facilitated development of the following guideline to antibiotic choices in Intra-abdominal infections. Background Intra-abdominal infection is often triggered by GI perforation leakage of gastrointestinal contents with development of generalized peritonitis or abscess in the abdominal cavity. The majority of intra-abdominal infections are characteristically ‘secondary bacterial peritonitis.’ Hollow viscus perforation accounts for 60-80% of all reported cases of secondary peritonitis. Surgical intervention is often required expeditiously to improve patient outcomes. Summary Antibiotic regimens for intraabdominal infections based on FHA Formulary Low-risk patients Antibiotic Regimen (average doses listed)a Cefazolin 1 g IV Q8H Or Cefuroxime 750 mg IV Q8H Plus Metronidazole 500 mg IV Q8-12H Gentamicin 2.5 mg/Kg mg IV Q8Ha Plus Metronidazole 500 mg IV Q8-121H Or Clindamycin 600 mg IV Q8H b High-risk patients (always consider confounding factors such as immune status, sepsis, etc.) Drug cost per day $11.22 $8.85 $3.66 $8.31 $7.14 $3.66 Ertapenem 1g IV Q24H $49.95 Ticarcillin/Clavulinate 3.1g IV Q6H Cetriaxone 1 g IV Q24H Plus Metronidazole 500 mg IV Q8-12H $38.44 $34.00 $3.66 Gentamicin 2.5 mg/Kg mg IV Q8Ha Plus Metronidazole 500 mg IV Q8-12H Or Clindamycin 600 mg IV Q8H b (+/- Ampicillin 1G IV Q6H) $8.31 $7.14 $3.66 $3.00 Ciprofloxacin 400 mg IV Q12Hc Plus Metronidazole 500 mg IV Q8-12H $66.00 $3.66 Piperacillin/tazobactam 3.375 mg IV Q6H $62.28 Imipenem/cilastatin or Meropenem 500 mg IV Q6H $97.52 CONFIDENTIAL for Quality Improvement Purposes only. Page B Catastrophic Case Report Acute Abdomen: Diagnostic Imaging and Antibiotic Choices Brian McGowan, MD; Lily Cheng, PharmD The ‘acute abdomen’ is a general term applied to any patient presenting with severe, acute abdominal pain. In these cases, the examining physician searches for the etiology with some urgency, as these patients often require either hospital admission and/or surgical intervention. Evaluation of these patients starts with "making a serious and thorough attempt at diagnosis, usually predominantly by means of the history and physical examination." A recent FH case illustrates some of the difficulties encountered in managing these cases. CASE REPORT A patient was sent to the ER by a clinic physician with presumptive diagnosis of “Perforated Viscus.” The patient had a board-like abdomen severe pain and elevated WBC. Abdominal plain films were normal and were repeated after the gastric insufflation of 500cc air by an NG tube. The second set of films was also negative at about midnight. The patient was admitted for observation and prescribed Morphine, Cefazolin and Metronidazole. During the night there was progressive development of sepsis. The patient had a CT scan of the abdomen the following morning. This demonstrated a small amount of free intraperitoneal air and thickening of the mid small bowel wall. The patient was taken to the OR and died immediately after resection of a perforated segment of small bowel was removed. Pathology revealed a small bowel lymphoma with perforation. Cause of death was sepsis secondary to bowel perforation and peritonitis. CASE REVIEW Two concerns stood out in the review. Why was an abdominal CT not performed when plain films were negative? Why was Cefazolin/Flagyl chosen as antibiotic coverage? These questions will be looked at separately but should not take away from the dominant concern. This patient presented with a “Rigid Abdomen” and early surgical intervention was likely the preferred approach. Diagnostic Laparotomy is a very valuable tool in the General Surgeons practice and watchful waiting or protracted delays for diagnostic work up should not delayed needed Surgery. “Rigid Abdomen” - early surgical intervention was likely the preferred approach.” CT SCAN IN ACUTE ABDOMEN CT has become the front line diagnostic tool to aid history and physical exam in the evaluation the acute abdomen. Despite good clinical skills, there are times and circumstances where CT is essential in the disposition and management of a patient. This is especially true when the clinical presentation is confusing. In some cases of acute appendicitis or diverticulitis with abscess formation, the accurate diagnosis of the problem can lead to non-operative, image-guided, percutaneous therapy. In small perforations (as in this case), ischemic bowel or a closed loop small bowel obstruction, the rapid diagnosis by CT may facilitate surgery. CONFIDENTIAL for Quality Improvement Purposes only. Page C CT TECHNIQUES IN THE ACUTE ABDOMEN Plain abdominal films have limited utility but can reveal the presence of an ileus or bowel obstruction, free intraperitoneal air, ascites and interstitial gas. CT is supplanting plain films as the imaging procedure of choice in the Acute Abdomen. The advantages of CT include versatility and a wide margin of error. It provides a global survey of the abdomen, presents useful surgical anatomy and detects pneumoperitoneum. There are five possible CT techniques in the evaluation of a patient with an acute abdomen: Plain CT; IV contrast; Oral and IV contrast; Rectal and IV contrast; Oral, rectal and IV contrast. Plain CT is the fastest, but most limited of the techniques. Some radiologists use this technique very effectively. It is important to at least have a working Differential Diagnosis in the patient evaluated for acute abdominal pain. The ideal strategy for CT in the acute abdomen is IV and oral contrast (occasionally with rectal contrast). With this technique, blood vessels and the bowel are opacified, extravasation is identified, abnormal enhancement can be detected (less inherent body contrast (fat) is useful for delineating margins). This technique can be time consuming and the patient must be cooperative with reasonable renal function and there can be contrast media reactions. IV contrast alone is convenient but with thin patients, bowel details are limited as fat is relatively absent. Rectal contrast alone yields a focused exam and is effective in diagnosing colonic disorders such as diverticulitis and appendicitis, but limits evaluation of the remainder of the exam. CT-THE ACUTE ABDOMEN: COMMON DIAGNOSIS Appendicitis In most patients, especially in men, the clinical diagnosis of acute appendicitis is straightforward and does not necessarily require imaging confirmation unless the presentation is atypical. In patients with a confusing clinical picture, especially in the aged and females, the diagnosis can be very difficult. The differential diagnosis of findings in the right lower quadrant is important and includes, right sided diverticulitis, renal colic, PID, infectious or inflammatory disease and carcinoma of the Cecum or Appendix. Asians have a higher incidence of right-sided diverticulitis. In an early retrospective study of 100 patients with atypical or non-specific clinical presentation, the sensitivity and specificity was 98% and 83% respectively. A diseased appendix was present in 45/50 and appendicoliths in 17/60 (an appendicolith is diagnostic). Recent studies have noted an increased incidence in perforations and complications when patients are required to have a CT scan prior to Appendectomy. The CT diagnosis of acute appendicitis is based upon detecting one or two positive findings. The abnormal appendix is visualized as a distended, fluid-filled, thickwalled tubular shaped structure located to the right of the midline from the subhepatic space to the pelvis. It is often associated with soft tissue changes in the peri-cecal fat. CT studies have confirmed that some cases of acute appendicitis can resolve with conservative treatment. Smouldering acute appendicitis or missed acute appendicitis with rupture can have the appearance of a tumour. It is also important to note that CT can guide management in patients with complicated appendicitis. In one four-year study of 70 patients with suspected peri-appendiceal inflammatory masses, three management groups were created. Those patients with a peri-appendiceal phlegmon of small abscesses were initially treated with antibiotics alone. Those with well-defined peri-appendiceal abscesses were treated with CT guided percutaneous catheter drainage with complete resolution in almost all. Lastly, those patients presenting with multilocular/ multi-compartmental abscesses were immediately explored and drained. CONFIDENTIAL for Quality Improvement Purposes only. Page D Bowel Obstruction Plain films of the abdomen detect small bowel obstruction in about 60-70% of cases. Differentiating ileus from incomplete or subacute bowel obstruction can be extremely difficult. The CT findings of a small bowel obstruction include the presence of small bowel dilatation (a lumen of greater than 2.5 cm) and the presence of a transition point (e.g. collapsed distal bowel). In one series, there was about 95% sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of a small bowel obstruction. About 50% of patients with a strangulating obstruction are not clinically diagnosed pre-operatively. CT findings of a closed-loop and strangulating intestinal obstruction are helpful in many of these cases. When a small bowel obstruction is present, ischemic changes of the small bowel can occur even without strangulation or entrapment. In one study of patients with this type of ischemic bowel there were no false negative CT diagnoses but there were 12 false positives (specificity was 61%). CT is highly sensitive but not as specific. Acute Diverticulitis CT has become the imaging procedure of choice in the diagnosis and management of patients with acute diverticulitis. Recent studies have demonstrated CT sensitivity of 97% and a specificity of 100%. Importantly, alternative diagnoses are often identified on CT in over half of the patients thought to have diverticulitis pre scan. Ultrasound has about 85% sensitivity and specificity. The CT typically reveals wall thickening, peri-colic fat changes and abscess formation. Other findings include fistulae, bowel or ureteric obstruction and peritonitis. Localized abscess formation is seen in 35-50% of patients. If an abscess is detected, it is common practice to percutaneously treat if technically feasible. The objective is percutaneous resolution of the abscess so the patient will avoid surgery. Other Causes of Acute Abdominal Pain Detected on CT Ischemic bowel is a common cause of acute abdominal pain in the aged vasculopath patient. No imaging procedure is reliable for these cases but CT is probably the imaging procedure of choice. Unfortunately CT is limited because the most common findings: bowel dilatation, thickening of the bowel wall and a negative scan do not exclude the diagnosis of ischemic bowel. With the increasing use of CT in the evaluation of any patient with acute abdominal pain, there are a number of findings unexpectedly detected. A perforated duodenal ulcer is not uncommonly diagnosed on a CT. Most of these patients have a pneumoperitoneum as well as soft tissue changes adjacent to the stomach and/or duodenum. Acute cholecystitis is also found on CT. Patients are usually sent to CT because of confusing findings including non-localized right-sided abdominal pain. The query in these cases is acute appendicitis vs. acute cholecystitis or some other cause. CONFIDENTIAL for Quality Improvement Purposes only. Page E ROLE OF CT IN THE EVALUATION OF THE ACUTE ABDOMEN In one review of 40 admitted patients with “Acute Abdominal pain NYD”, CT showed intestinal obstruction in about 40%. Other CT diagnosis included peritonitis, inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, mesenteric ischemia, pancreatitis, cholecystitis and hemo-peritoneum. The pre-CT clinical diagnosis was correct 17.5% of the time while the post-CT diagnosis was accurate 60% of the time. In another retrospective study, 91 patients admitted with acute abdominal pain and initially treated conservatively were scanned because of a failed response to initial conservative therapy. Most of these patients were evaluated within 24 hours. Clinical diagnosis was correct in about 60% while CT was correct 85% of the time. CT findings changed therapy in 25 patients; surgery instead of medical therapy was performed in 15 more cases. As a final comment to this discussion I asked an FH CT Radiologist to sum up their suggested approach. They replied: “In my take of the radiology literature, the consensus is that CT with IV contrast medium offers the most "bang for the buck". In most cases oral and rectal contrast medium do not add much more (and are time consuming). Non IV contrast studies may be fine in people with intra-abdominal fat, but in thin people the images may be hard to interpret. Of course, any CT is better than none or just plain radiographs. In patients with "typical" appendicitis”, the surgeon may choose to take the patient to OR without a CT scan. Often though, there is enough time to get CT so that there are no surprises for the surgeon. In children and young women, US may be the first line imaging, even though not as sensitive or specific as CT. Of course, one may get a non diagnostic US and then still need to resort to CT.” ANTIBIOTIC CHOICES FOR INTRA-ABDOMINAL INFECTIONS (possible perforated viscus) This patient was given a standard cocktail of Cefazolin and Flagyl for possible perforated viscus. A random survey of 15 Emergency Physicians, Surgeons and Internists revealed a variable approach to empiric treatment of “Acute Abdomen”. A review of the literature and consultation with local experts has facilitated development of the following guideline to antibiotic choices in Intra-abdominal infections. Background Intra-abdominal infection is characterized by the presence of gastrointestinal contents or pus in the form of abscess or generalized peritonitis, in the abdominal cavity. Important differences exist between intraabdominal infection and peritonitis. Peritonitis is classified as primary, secondary and tertiary. Primary peritonitis is infection without an evident infectious source, whereas secondary peritonitis is caused by leaked gastrointestinal, genitourinary or other infected fluids in the peritoneal space. Tertiary peritonitis is less welldefined, characterized by persistent or recurrent infections with low virulence organisms and is usually associated with a systemic inflammatory response syndrome. The majority of intra-abdominal infections are characteristically ‘secondary bacterial peritonitis.’ They are typically caused by a loss of gastrointestinal wall integrity secondary to trauma, surgery or intrinsic disease. Hollow viscus perforation accounts for 60-80% of all reported cases of secondary peritonitis. Surgical intervention is often required expeditiously to improve patient outcomes. Microbiology Antibiotic therapy is dictated by common GI tract micro organisms. Intra-abdominal infections are usually polymicrobial, involving aerobic and anaerobic enteric organisms. The bacteria isolated depend on the level of the perforation. The upper GI tract flora has a higher likelihood of gram-positive organisms along with gram- CONFIDENTIAL for Quality Improvement Purposes only. Page F negative organisms; whereas the lower tract flora is mostly gram-negative and anaerobic. Escherichia (E.) coli is the most commonly encountered enteric aerobe, and Bacteroides (B.) fragilis is the most frequent anaerobe. (Table 1) Table 1. Micro organisms isolated from intraabdominal infections Gram-positive aerobic and facultative Gram-negative aerobic and facultative Anaerobic Micro organisms Enterococcus sp. Non-enterococcal Streptococcus sp. Staphylococcus sp. Escherichia coli Enterobacter sp. Klebsiella sp. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Other gram-negative enteric bacilli Bacteroides fragilis Other Bacteroides sp. Clostridium sp. Peptostreptococcus Streptococcus Low-Risk versus High-Risk Infections Community-acquired intra-abdominal infections are often low-risk infections, (e.g. perforated appendicitis, diverticulitis). Omental walling and localization of abscess may occur in visceral perforation, causing “localized” peritoneal irritation. Infections with general peritonitis, SIRS/sepsis, nosocomial infections and infections in immunocompromized hosts are high risk. In community-acquired infections, the common aerobic and anaerobic enteric flora are usual, with less concern about Enterococcus species. Nosocomial infections may involve more resistant gram-negative organisms, such as Pseudomonas sp., Enterococcus sp, MRSA and Candida sp. Antibiotic Therapy The goal of antibiotic therapy is to eradicate infection, prevent recurrent infection, reduce surgical wound complications and control bacteremia/sepsis. The use of empiric broad-spectrum antimicrobial coverage is recommended to cover aerobic organisms, facultative Enterbacteriacae and anaerobic organisms, such as B. fragilis. The Infectious Disease Society of America and the American Surgical Infection Society supports the use of targeted emperic therapy for the treatment of intra-abdominal infections. (Table 2) Monotherapy and combination therapy are comparable in efficacy. A recent Cochrane Evidenced based review/meta-analysis demonstrated that all antibiotic regimens had equivocal clinical success. CONFIDENTIAL for Quality Improvement Purposes only. Page G Table 2. IDSA and Surgical Infection Society Guidelines Antibiotic Regimen Single Therapy Low Risk Cefoxitin High Risk Imipenem/cilastatin or Meropenem Ertapenem Combination Therapies a b c Ticarcillin/clavulanate Piperacillin/tazobactam Aminoglycosidea + metronidazoleb Aminoglycosidea +Metronidazoleb Cefazolin or Cefuroxime + Metronidazole Ciprofloxacina + Metronidazoleb Ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin or moxifloxacinc + Metronidazoleb 3rd or 4th gen Cephalosporin + Metronidazoleb Aminoglycoside = gentamicin, or tobramycin; Clindamycin may be used as an alternative. There have been reports of increasing resistance of B fragilis to clindamycin, cefoxitin and fluoroquinolones. Fluoroquinolones have shown increasing resistance of E.coli and B. fragilis. Please review susceptibility patterns prior to starting fluoroquinolones and follow up with culture & sensitivity reports. Recommendations based on Antibiotics on Fraser Health Formulary Based on the evidence of comparable efficacy, choice of antibiotic therapy should be dictated by local antibiogram data, possible adverse effects, cost, preparation time and health care provider time. Of note, there have been recent reports of increasing rates of B. fragilis resistance to clindamycin, cefotetan, cefoxitin and fluoroquinolones. As well, there is increased rates of E.coli resistance to Fluoroquinolones. (contact your local Pharmacy Department or Microbiology Department for the 2007 FHA Antibiograms.) In general, most patients can be empirically started on a cephalosporin plus anti-anaerobic agent. In patients with a penicillin allergy, an aminoglycoside plus anti-anaerobic agent can be used. Recommendations for the antibiotic regimens available on the Fraser Health Formulary are listed in Table 3. 1) In low-risk patients with community-acquired intraabdominal infections, empirical coverage against Enterococcus sp. and Pseudomonas sp. is not necessary. 2) In high-risk patients and in patients with anticipated prolonged hospital stay, extended coverage against most Gm (-) aerobic/facultative anaerobic organisms is recommended. Several risk factors associated with treatment failure and increased mortality have been identified in the literature. These high-risk features include advanced age, poor nutritional status, a low serum albumin concentration, pre-existing medical disorders such as significant cardiovascular disease, a higher APACHE II score, and the presence of resistant microorganisms. These patients should have extended coverage for Pseudomonas sp. Coverage for Enterococcusl sp. is not routinely recommended, but should be considered in patients that are at higher risk of health care associated infections or when guided by microbial culture results. CONFIDENTIAL for Quality Improvement Purposes only. Page H Duration of Therapy The optimal duration of therapy for intraabdominal infections remains controversial. In prospective, randomized studies, the duration is usually determined at the discretion of the investigators and may range from 3 to 14 days or longer if needed. Based on limited clinical data and expert opinion, the Surgical Infection Society recommends treatment to be limited to no more than 5 to 7 days for most patients with complicated intraabdominal infections. In general, antibiotics should be continued until the resolution of clinical signs of infection, including normalization of temperature, WBC count and return of gastrointestinal function. If there is persistent or recurrent evidence of infection after 5 to 7 days of therapy, then appropriate diagnostic investigations should be undertaken. Table 3. Antibiotic regimens for intraabdominal infections based on FHA Formulary availability Low-risk patients Antibiotic Regimen (average doses listed)a Cefazolin 1 g IV Q8H Or Cefuroxime 750 mg IV Q8H Plus Metronidazole 500 mg IV Q8-12H Gentamicin 2.5 mg/Kg mg IV Q8Ha Plus Metronidazole 500 mg IV Q8-121H Or Clindamycin 600 mg IV Q8H b High-risk patients (always consider confounding factors such as immune status, sepsis, etc.) Drug cost per day $11.22 $8.85 $3.66 $8.31 $7.14 $3.66 Ertapenem 1g IV Q24H $49.95 Ticarcillin/Clavulinate 3.1g IV Q6H Cetriaxone 1 g IV Q24H Plus Metronidazole 500 mg IV Q8-12H $38.44 $34.00 $3.66 Gentamicin 2.5 mg/Kg mg IV Q8Ha Plus Metronidazole 500 mg IV Q8-12H Or Clindamycin 600 mg IV Q8H b (+/- Ampicillin 1G IV Q6H) $8.31 $7.14 $3.66 $3.00 Ciprofloxacin 400 mg IV Q12Hc Plus Metronidazole 500 mg IV Q8-12H $66.00 $3.66 Piperacillin/tazobactam 3.375 mg IV Q6H $62.28 Imipenem/cilastatin or Meropenem 500 mg IV Q6H $97.52 a Average doses listed; may modify as appropriate to tailor to the needs of the patient. Consult local clinical pharmacist for assistance b There have been reports of increasing resistance of B fragilis to clindamycin, cefoxitin and fluoroquinolones. c There have been reports of increasing resistance of E. coli to fluoroquinolones. Local antibiogram patterns should be reviewed prior to starting Fluoroquinolones, and culture and sensitivities should be followed. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Many thanks to Dr. Yasemin Arikan and members of the FHA Infectious Diseases Subcommittee for their review and feedback. CONFIDENTIAL for Quality Improvement Purposes only. Page I REFERENCE MATERIALS 1. Mindelzun RE, Jeffrey RB The acute abdomen: current CT imaging techniques. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 1999; 20:63-6 2. Malone AJ Unenhanced CT in the evaluation of the acute abdomen: the Community Hospital experience. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 1999; 20:67-76 3. Lane MJ, Mindelzun R Appendicitis and its mimickers. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 1999; 20:77-85 4. Balthazar EJ, Liebeskind ME, Macari M Intestinal ischemia in patients in whom small bowel obstruction is suspected: evaluation of accuracy, limitations, an clinical implications ofCT in diagnosis. Radiology 1997; 205:519-522 5. Maglinte DDT, Balthazar EJ, Kelvin FM, Megibow AJ The role of radiology in the diagnosis of smallbowel obstruction. AJR 1997; 168:1171-1180 6. Taourel P, Baron MP, Pradel J, Fabre JM, Senterre E, Bruel JM Acute abdomen of unknown origin: impact of CT on diagnosis and management. Gastrointes Radiol. 1992; 17:287-291 7. Siewert B, Raptopoulos V CT of the acute abdomen: findings and impact on diagnosis and treatment. AJR 1994; 163:1317-1324 8. Siewert B, Raptopoulos V, Mueller MF, Rosen MP, Steer M Impact of CT on diagnosis and management of acute abdomen inpatients initially treated without surgery. AJR 1997; 168:173-178 9. Federle M Focused appendix CT technique: a commentary. Radiology 1997; 202:20-21 10. Rao PM CT of diverticulitis and alternative conditions. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 1999; 20:86-93 11. Bohnen JMA. Antibiotic therapy for abdominal infection. World J Surg 1998;22:152-57. 12. Farthmann EH, Schoffel U. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of intraabdominal infections (IAI). Infection 1998;26:329-334. 13. Levison ME, Bush LM. Peritonitis and other intraabdominal infections. In Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Raphael D (eds): Principles and practice of infectious diseases. Churchill Livingstone, Philadelphia 2000. 14. Nathens AB, Rotstein OD. Antimicrobial therapy for intraabdominal infection. Am J Surg 1996;172(Suppl 6A):1S-6S. 15. Mazuski JE, Sawyer RG, Nathens AB, et al. The surgical infection society guidelines on antimicrobial therapy for intraabdominal infections: evidence for the recommendations. Surg Infect 2002;3(3):175233. 16. Solomkin JS, Mazuski JE, Baron EJ, et al. Guidelines for the selection of anti-infective agents for complicated intra-abdominal infections. 17. Wong, PF, Gilliam AD, Kumar S, et al. Antibiotic regimens for secondary peritonitis of gastrointestinal origin in adults. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006;1 CONFIDENTIAL for Quality Improvement Purposes only. Page J