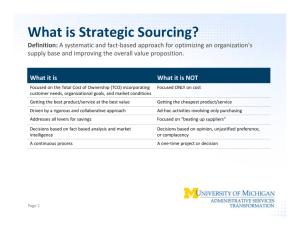

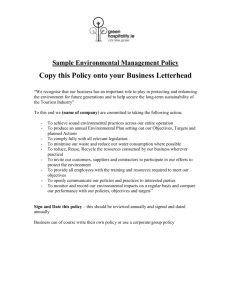

Graph 1: The four main classes of inter

advertisement

Hugues Poissonnier Grenoble Ecole de Management International Sourcing and Sustainable Development through Industrial Upgrading : The Case of Inter Organizational Control Practices developed by French Clothing Retailers Abstract In this paper, the problem of sustainable development in the context of inter-organizational relationships is investigated. To do so, we focus our analysis on the link between international sourcing practices and industrial upgrading opportunities offered to the suppliers and study the case of the apparel industry which is one of the most globalised ones with different operations being spread around different locations. The importance of textiles and clothing for the trade development of developing countries has been indeed widely described. In a context of great competition, in which time, price and quality of the products are more and more important, sourcing practices have evolved during the recent years. Those evolutions can be described in terms of sourcing geography or relationships. Meanwhile, the clothing sector in developed countries has been at the forefront of efforts to raise the social and environmental standards of trade. We assume that, to understand and analyze those evolutions, as well as the question of development opportunities linked to international trade, one of the main important questions that have to be tackled is the question of interorganizational control. Studies focused on the concept of global commodity chains (GCC) are used as a theoretical frame of reference. The concept of GCC is indeed very useful to analyze the evolutions and the impacts of inter-organizational relationships for distributors and producers, putting the questions of power and control at the heart of the analysis. The management of inter-organizational relationships by French clothing retailers is analyzed and described as an example of the evolutions of sustainable development practices that are implemented today. Key words Sustainable development, International sourcing, Industrial upgrading, Inter-organizational control, Clothing 1 Introduction The degree of international dispersal observable in the clothing and textile sectors explains the interest that is given to questions linked to sustainable development in researches that have been conducted recently (Gibbon, 2000, 2001; Gereffi, 1999; Henderson & al., 2002; Palpacuer & Poissonnier, 2003; Palpacuer & Parisotto, 2003;…). Being an industrializing industry, the clothing industry is frequently chosen by countries as a way to develop. The evolution of apparel production in the East Asian Tigers could be taken as a benchmark by producers located in developing countries. One should however remember that the East Asian nations present specificities that, to a certain extent, explain their growth and the upgrading of the firms. The first one is linked to their colonial and post-colonial experiences. Because of the geopolitics of the 1950s and 1960s, they received massive foreign assistance from the United States, while regional investments from Japan were increasing (Kessler, 1999). Moreover, historically speaking, the period in which their development occurred coincided with a great expansion in world trade in manufactured commodities while international competition among producers was not as important as today. In spite of this, the way in which East Asian producers have been networked to and embedded in GCCs has undoubtedly been a key determinant in their successful economic development. The question that arises is then the one of the potential developing countries have to make their developmental trajectory match the one of the East Asian countries by producing garments. The recent removal of the quota system (termination of the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing) and the implementation of a quota-free environment should translate into substantial and tangible benefits for the development of developing and least-developed countries (Hotopp & al., 2005). However, the implications of changes in retailers’ global sourcing practices are sometimes dramatic for suppliers (Gibbon, 2000; Agndal & Axelsson, 2002). We assume that the nature of the relationships between distributors and suppliers can be seen as a key determinant for the industrial upgrading opportunities that are given to suppliers. Retailers in developed countries have then an obvious responsibility in the development of their suppliers and their countries. The way retailers use or abuse of their power (in terms of bargaining as well as in terms of control) structures the learning possibilities and industrial upgrading opportunities that are offered to suppliers. Cherret (1994) explains for example how partnering can be a source of upgrading by allowing the development of competitive advantages. Nevertheless, it should not be forgotten that there are examples of negative effects linked to partnering which can notably prevent suppliers to develop new and successful relationships (Donada, 1997). As important actors in the globalization process, clothing distributors should then not ignore the questions of their suppliers’ industrial upgrading opportunities and of sustainable development. We assume that, by their decisions, retailers are able to expand or reduce exports of “sustainable goods and services” from the developing countries and to develop what could be called “sustainable purchasing”. The question we will tackle in this paper is then the following: How does the definition of inter-organizational control practices structure the industrial upgrading opportunities that are given to suppliers? 2 The implications of globalization for the retailers and their sourcing practices have been largely tackled in the literature (Arnold, 1989; Alguire & al., 1994; Amin, 1994; Araujo & al., 1999, Bensaou, 1999; Cho & Kang, 2001; Clark, 2002; Trent & Monczka, 2002) but few studies focus on these implications for the suppliers and their countries (even if we should mention the interesting study conducted by Ernst (2000)). We start by an analysis of the links between international trade and sustainable development in the clothing industry, insisting on the importance of inter-organizational control and relying on an analysis based on the global commodity chain ( I ). We then present a study of control practices developed by French distributors drawing on a brief presentation of the French clothing retail market that explain the dominant form of relationships and control practices that are set on suppliers. The most important evolutions (development of outsourcing practices, geography of sourcing, formalization of control practices,…) are addressed in this section. We then insist on the implications of the situations described on the upgrading opportunities offered to the suppliers ( II ). I ) International trade and sustainable development in the clothing sector: the importance of the question of inter-organisational control Whether it is working conditions or environmental problems, clothing retailers are under pressure to demonstrate responsible practices along their supply chains. This ethical imperative is driven by the accelerating globalisation of sourcing, which is opening up new opportunities for textile and garment producers in the developing world. We will first explain our choice of the apparel industry which is one of the oldest and largest export industries in the world (Dickerson, 1991) (1.1). We will then describe industrial upgrading as a privileged way for developing countries suppliers to develop (1.2) and highlight the relevance of an analysis based on the GCC perspective (1.3). 1.1 ) The choice of the clothing industry The clothing industry has been long seen as a stepping-stone to industrialization. Apparel is indeed a typical starter industry for countries engaged in export-oriented industrialization. It has played this role of industrializing industry in Europe during the 19th century, as well as in East Asia more recently (during the 1970s). According to Palpacuer & al. (2005), the sector played four important roles in these countries’ economic development. The first one is linked to the fact that it absorbed large magnitudes of unskilled labour. Secondly, the goods it produce are aimed at satisfying elementary needs for large segments of the domestic population. Thirdly, despite low investment requirements, it served to build capital for more technologically demanding production in other sectors. To conclude, it financed imports for more advanced technologies by generating export earnings (as well as by substituting imports). Producers’ innovation capacities are also very important. Gereffi (1999) insists on the relevance of the East-Asia suppliers’ capacity to move from the mere assembly of imported inputs to a more domestically integrated and higher value-added form of exporting. Several other reasons can be found to explain this historical role. One of them is linked to the low entry barriers in terms of skills and capital requirements in the apparel industry. The ease of transportation, due to the light and non-perishable nature of garment products is another one, which allow many developing countries to produce for export markets. They are then able to find abroad the customers who do not exist inside the country’s frontiers. 3 In spite of this historical role of the clothing industry, the question of its new industrializing potential should be tackled. Since the 1990s, powerful forces are transforming clothing retail in most of the developed countries (Bailey, 1993; Rollins & al., 2002). Fashion cycles are shortening, new entrants are shaking established actors and e-commerce promises to deliver further shocks. To respond to those evolutions and anticipate the next ones, retailers have engaged themselves in a process of bringing down costs and improving quality. To do so, they rationalise their supply base. During the recent years, externalization has developed as well as competition in terms of price, time and quality of the products. Being globally competitive has become a greater necessity for the producers and several authors have showed how the clothing industry was dominated by retailers located in developed countries (Appelbaum & Gereffi, 1994; Chacon, 2000; Gibbon, 2001). Those last ones set the terms of trade for price, quality and delivery within the supply chain in what we could call a “buyers market”. That is why, in spite of the historical examples we have mentioned, two questions should be addressed: is it today as easy as in the past to succeed in the clothing industry for a producer and is the eventual growth still a sufficient condition to serve as a means of domestic capital accumulation and to favour sustainable development? Before answering these questions, we will present industrial upgrading as a possible way to engage in sustainable development. 1.2 ) Industrial upgrading as a way to engage in sustainable development The main idea we develop in this paper is that the nature of the relationships between distributors and suppliers can be seen as a central determinant for the industrial upgrading opportunities that are given to suppliers. Distributors in developed countries have then an obvious responsibility in the development of their suppliers, for themselves and their countries. First of all, we will present the benefits of subcontracting as they are described in the literature. We will then tackle the issue of the links between international trade and sustainable development, insisting on the role of industrial upgrading. We will then conclude this section by a presentation of the dimensions and conditions of industrial upgrading. The benefits of international subcontracting Watanabe (1971, 1978) showed how local producers could gain benefits from international subcontracting. Working on relationships between Japanese lead firms and their subcontractors, the author describes different kinds of benefits, in terms of accessing distant markets and obtaining know-how. Hakansson & al. (1999) confirm the positive effects of “learning by doing” that were described by Arrow (1962). Another way of learning results of the “organizational transmissions” that are described by Kalika & al. (1998) which consist of making the organizational structures evolve to be more efficient. Such transfers have been pointed out by Kessler (1999) and Bair & Gereffi (2002) in the context of Nafta. On the other side, Dussel & al. (1997) argue that there are several limits at considering foreign partners as teachers, owing to the fragility of business relationships. International trade and sustainable development As stated in the “Brundtland Commission Report” of 1987, Our Common Future, sustainable development is development which “meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. A distinction is generally made between three great dimensions of sustainable development which are the social, the 4 environmental and the economical concerns. However, the Brundtland Report argues that those three dimensions are linked and that the best way to fight against environmental degradation is to facilitate the development of nations. Poverty is indeed the most important contributor to environmental degradation, as it encourages the overuse of scarce environmental resources to meet survival needs. That is why the reduction of trade barriers can be seen as a good way to limit “pollution of poverty” by generating the resources needed for environmental protection. Trade, in a way, contributes to saving people from the vicious cycle of having to degrade their environment to survive (Sorensen, 2001). According to this, we can consider that a strong link exists between trade, the economic growth it permits and development from both a social and environmental point of view. Moreover, actions carried out by NGO develop and could be analysed as a response to problems that are linked to globalization. One of the most important problem that legitimate NGOs’ actions is the one of sweatshops, which has been largely tackle in the literature (Firoz & Ammaturo, 2002; Harrison & Scorse, 2006), as well as the problem of child labor (Bachman, 2000). Thus creating conditions for free international trade is key to raising the standard of living of the current generation and to allowing future generations to enjoy environmental resources which will be better protected (Sorensen, 2001). If it is a necessary condition, we assume it should not be considered as a sufficient condition. Industrial upgrading is not that easy for producers in the clothing industry since the diffusion of recent changes. For a better understanding of these difficulties, several dimensions of industrial upgrading should be distinguished. The dimensions and conditions of industrial upgrading Upgrading means enhancing the relative competitive position of a firm, which can be achieved in different areas (Schmitz & Knorringa, 2000). Firms can upgrade their processes (“doing things better”) or products (“making better things”). They can also move into higher value added stages in the chain like design or marketing (Schmitz & Knorringa, 2000), which is called “functional upgrading” by Humphrey & Schmitz (2000). More generally speaking, four great dimensions of industrial upgrading have been distinguished in the literature. The first one is called service-based upgrading and consists of performing a broader range of services beyond simple assembly, including product design, inventory management or management of production sourcing. The second can be called volume-based upgrading. It gives the possibility to reduce unit production costs on the basis of scale economies. We can then speak about process-based upgrading which allow a reduction of inventories and waste through the adoption of lean production systems. Then, the product-based upgrading can be defined as suppliers’ ability to manufacture higher quality products for higher price market segments. Several authors have tackled the question of the determinants of success in inter-firm relationships (Ford, 1980; Ford & Hakansson, 2002) defining this success in terms of maintenance of the relationship. The role of the nature of the relationship while explaining the differences between learning opportunities linked to inter-firm relationships has then been largely pointed out. As Ring & Van de Ven (1992, 1994) note, trust between partners is essential for the structuring of cooperative relationships. Van de Ven (1976) presents trust as the most important conditions for the maintenance of relationships among organizations. Their findings are confirmed by several studies (Ganesan, 1994; Mohr & Spekman, 1994; Monczka & al., 1995; Zaheer & al., 1998). Trust is also presented as having powerful effects on performances improvement (Dyer & Chu, 2003). 5 1.3 ) The relevance of an analysis based on Global Commodity Chains (GCC) In this section, we will present the GCC (also called Global Value Chain) approach. After a focus on the central role of control in this approach, we will describe the main international differences that can be seen in the clothing industry in terms of GCC. The GCC approach During the recent years, several transformations affected many industries. The manufacturing process is becoming more and more trans-national (Abernathy & al., 1999). Hopkins and Wallerstein (1994) define commodity chains as “a network of labor and production processes whose end result is a finished commodity”. For Gereffi (1999), a commodity chain refers to “the whole range of activities involved in the design, production, and marketing of a product”. Gibbon (2003) confirms those approaches by describing networks of production, distribution and marketing of particular products or groups of products. A global commodity chain could thus be viewed as “a microcosm of the capitalist world economy” (Kessler, 1999). The GVC approach is very useful for highlighting the role of power relations in shaping the distribution of value across the range of countries and firms participating in GVCs (Kaplinsky, 2000). It can also be used to assess the development potential that such chains might offer to suppliers located in developing countries. The idea that is developed here is that the structure and dynamics of GCCs have important implications for suppliers’ ability not only to enter these chains, but also to engage in a process of “industrial upgrading”. According to Gereffi (1999), developing countries producers need access to the chains’ lead firms to upgrade (North American or Western Europe firms). These access to the world’s main markets can be direct, by becoming a supplier, or indirect, by becoming a second-tier supplier. Gereffi (1999) explains that producers that gain access have good prospects for upgrading within production and then into design, marketing and branding. The central role of control The importance of the question of control in inter-firm relationships has been pointed out by several authors in dyadic context as well as in network (Otley, 1994; Heide, 1994; Hopwood, 1996; Birnbirg, 1998; Van der Meer-Kooistra & Vosselman, 2000; Cox & al., 2001; Dekker, 2004). The main components of a commodity chain can be defined as comprising an inputoutput structure, a specific geography and an internal governance structure. It is the emphasis on this last element which differentiate the GCC analysis from other analysis of international commodity trade. The notion of “internal governance structure” was elaborated in relation to the distinction between “buyer-” and “producer-driven” commodity chains (Gereffi, 1999). According to this conception, the nature of specific categories of leading agents determine both input-output structures and chain geographies (Gibbon, 2003). “Producer-driven” commodity chains are those in which large manufacturers play the central role in coordinating production networks whereas “buyer-driven” chains are observable in industries in which large retailers, branded marketers, and branded manufacturers play the pivotal roles in the coordination process. The garment chains are governed by global buyers and supplied by local producers from developing countries. The GCC approach is then well adapted to study the way relationships between distributors and producers are designed and governed. This approach reveals that the international dispersion of production across countries is predominantly organised by firms located in developed countries (Palpacuer & Poissonnier, 2003). The GCC analysis allows 6 Gereffi (1994, 1999) to describe clothing as a sector characterized by a high concentration of profits and control in the functions of marketing/distribution and retailing, and by the outsourcing of production on the basis of “buyer driven” networks of independent manufacturers, located mainly in developing countries. Dicken (1998) gives a representation of the textiles-clothing production chain highlighting the buyer-driven nature of the apparel commodity chain (figure 1). Figure 1: The textiles-clothing production chain Materials Processes End-users HOUSEHOLD GOODS Furnishings, Carpets, etc. 25% Natural fibres Raw cotton, wool, etc. YARN PREPARATION Spinning FABRIC MANUFACTURE Weaving/knitting,55 finishing DESIGN PREPARATION PRODUCTION 50% Standardized garments Chemical fibres Wood, oil, natutal gas Clothing industry Textile industry Chemical plants & petrochemical refineries PRODUCTION OF ARTIFICAL FIBRES a. cellulosics b. synthetics DISTRIBUTION Retail/wholesale operations Fashion garments 25% INDUSTRIAL GOODS Belting,upholstery for auto industry, etc. Source: Dicken (1998). The GCC approach put into evidence the asymmetry in bargaining position between leading global buyers and manufacturers from developing countries. Doing this, it offers a good starting point for discussing the circumstances in which buyers promote or hold back the upgrading of local producers (Schmitz & Knorringa, 2000). The more buyer-driven the chain is, the more the retailers are able to capture and control key segments of the chain, and the more, doing this, they determine the way in which industrial clusters develop and production networks are formed (Kessler, 1999). It is then possible to explore which type of chains are more likely to allow the various type of upgrading that would strengthen the competitiveness of producers from developing countries. International differences between the functioning of Global Commodity Chains Gereffi (1999) distinguishes different sourcing patterns for retailers in the US upper marketsegment (production by flexible enterprises based mainly in developed countries) and for branded marketers of basic clothing, many of whom had own-owned factories in the US and who were sourcing heavily from the Caribbean meanwhile. 7 Gibbon (2003) explains that deep segmentation exists between US-, EU- and Japanese endmarkets, giving the complex patchwork of international trade agreements (the Multifibre Arrangement and its successor, the Lomé Convention, NAFTA, and the EU’s Customs Union with Turkey, as well as its preferential trade arrangements (PTAs) with most Central and Eastern European and North African countries,…) a strong power of explanation. Moreover, Palpacuer & al. (2005) show that differences can be seen inside the European market between French, UK and Scandinavian markets. According to Gibbon (2001, 2002), the EU market for clothing is indeed itself internally segmented between member countries. This segmentation is undoubtedly linked to differences in terms of national cultures that have been highlighted by several authors (Black, 2001; Lane & Bachman, 1996). It can also be explained by the fact that their consumption trends and retail structures differ greatly as Whitley (1996, 1999) noted, insisting on the role of differences in terms of “Business Systems”. The first part of this paper was focused on the presentation of the links between international trade and sustainable development in the clothing industry. It allowed us to explain to what extent industrial upgrading of the producers could be considered as a good way to engage in sustainable development. Insisting on the importance of the question of control, we explained the relevance of an analysis based on Global Commodity Chains. The empirical focus, that we can now present, is the control practices developed by French retailers. The understanding of those control practices is indeed to provide a highlighting on industrial upgrading opportunities given to their suppliers by French retailers. II ) A study of control practices implemented by French retailers This study is aimed at exploring the upgrading opportunities that are given to suppliers in relation to the evolution of sourcing and control practices that are implemented by French retailers. After a presentation of the French clothing retail market (2.1), we will describe the methodology used (2.2) as well as the most important results we have found (2.3). 2.1 ) A presentation of the French clothing retail market : recent evolutions and implications for the suppliers In this section, we will first present the industry structure which will help to the understanding of the evolution of sourcing patterns addressed in the second time. The industry structure: the importance of hyper-markets and the rise of specialised chains Two major transformations can be observed in the French clothing retail sector since the mid1990s. The first one consists of a concentration of the hyper- and super-market segment resulting from mergers and acquisitions. The second one takes the form of a great development of specialised chains which characteristic is to sell their own branded products on the market. Hyper-markets entered the French clothing market during the 1960s and gained important market shares during the following decades. Even if their main activity still remains selling food, hyper- and super-markets have diversified their product offering to include textiles and clothing to the point that the top ten French clothing retailers include three hyper- and supermarkets, with Carrefour and Auchan in the two first positions. In recent years, the growth of large sports and discount chains such as Decathlon and Kiabi also boosted concentration 8 levels in the industry. In spite of these evolutions, concentration levels remains relatively low in France compared with the situation of the UK (Gibbon, 2002). The rise of specialized chains is the second major transformation that occurred in the French clothing market during the recent years. Many of these chains which appeared during the 1980s have their origins in the North of France (Camaïeu, Pimkie, Promod,…), while others, such as Naf Naf developed out of the Sentier in Paris. These specialized chains include smallstore chains such as Etam, Promod and Camaïeu in women’s wear, Celio, Brice and Jules in men’s wear, DPAM or Jacadi in children’s wear, and large-store chains that are either discounters such as Kiabi or La Halle, or sport chains such as Decathlon and Go Sport. According to Palpacuer (2004), the persistence of low concentration levels in the French clothing retail market can be explained by the importance of small specialized chains on the one hand and of family and management controlled ownership on the other. In spite of this, we can mention the rising concentration among the largest retailers and an important evolution in their capital structure witnessing a strategic shift towards “financialization” (Lazonick & O’Sullivan, 2000). Conditions are then set for important transformations to occur in French-driven GCCs. The evolution of sourcing patterns of French retailers The evolutions of the French retail scene involve new patterns in terms of sourcing. The necessity to develop specific products in terms of design, color,… has increased the need for quick turns that favour geographical proximity (Abernathy & al., 1999). Several authors have pointed out the effects of just-in-time purchasing both on the functioning of purchasing departments (Droge & Germain, 1997) and on buyer-seller relationships (Gilbert & al., 1994). Meanwhile, the increasing necessity to reduce costs involves an extent in sourcing geography and more concretely the increase of imports from Asia at the expense of Western European and Mediterranean countries (Monczka & Trecha, 1988). Several dominant orientations of sourcing strategy can be described. As noted by Palpacuer & Poissonnier (2003), the largest retailers, offering standardised products (hyper-markets and discount chains), are seeking to develop direct relationships with garment manufacturers, avoiding contacts with intermediaries such as importers and agents. The aim of “going direct” is explicitly associated with the rising importance of collections in these firms’ market strategies, and motivated their establishment of overseas buying offices in the late 1990s. Continuing the internationalisation of sourcing and increasing “reassorts” (replenishment for successful products) are the dominant orientations of women’s and children’s wear specialized chains. Another dominant orientation is to centralise and rationalise sourcing activities, witnessing the degree of informal and unstructured way of sourcing traditionally developed by French retailers (Palpacuer & Poissonnier, 2003). According to these strategies and to the recent shifts we have described, three buying methods are used by French retailers, corresponding to distinct distributions of production roles between buyers and sellers within the clothing chain: - “traditional buying” consists of acquiring a final product that has been designed and manufactured by an outside provider without retailer input; - buying a final product externally manufactured according to specifications provided by retailers; - arranging for outside product manufacturing by providing product specifications, fabrics and components to a “CMT” (Cut, Make and Trim) supplier. 9 The development of retailers’ own product collections and marketing strategies is associated with a shift away from the first buying form (Palpacuer & Poissonnier, 2003). This enables retailers to develop a better control on operations process, and on their suppliers and shape new kinds of global chains associated, as we will see in the next part, with new kinds of upgrading opportunities for the suppliers. As the authors note, French retailers’ sourcing networks appear to remain simultaneously more open and less closely integrated than those developed by leading American firms. This situation might offer greater industrial upgrading potential for suppliers working with French retailers than for those serving Anglo-Saxon markets, where established preferred supplier positions are protected by high entry barriers. Palpacuer & al. (2005) give three main explanations for the differences between sourcing practices observable in France, UK and Scandinavia, highlighting the origins of the specificities of the French retailers’ sourcing patterns we have described. First of all, the authors point out the role of the industrial structure. In a country in which larger firms exist, buyers are hypothesized to have more bargaining power in relation to suppliers. Even if the degree of concentration is not so high in France, retailers are the ones who design production networks. Secondly, the enterprise type seems determinant. Large chain stores are indeed characterised by the presence of a wide range of product types, many of which have short life cycles. They are also strongly interested in establishing a common “handwriting” across product in order to create differences in customers’ mind. These characteristics conduct these chains to ensure a high degree of internal coordination in their sourcing. Super or hypermarkets, selling products with longer life cycles and selecting suppliers on the basis of price rather that style, are more likely to attach less importance to ensuring such coordination. The authors give a third great factor of explanation which is ownership structure and show that publicly listed companies exhibit higher propensities toward out-sourcing of “non-core” competences owing to the doctrines of “shareholder value” requirements. After this presentation of the French clothing retail scene, we will describe the methodology we have used in constructing configurations of control modes aimed at understanding the different types of upgrading opportunities offered to their suppliers by French retailers. 2.2 ) Methodology: the construction of a taxonomy of inter-organisational control modes Starting from the relevance of the nature of inter-organizational control modes in explaining upgrading opportunities offered to suppliers, and from the existence of different types of inter-organizational relationships, we built a methodology consisting on the construction of a taxonomy of inter-organizational control modes. This last one is aimed at making configurations of inter-organizational control appear. A configuration can be defined as a constellation of variables or characteristics that commonly occur together and form a global configuration (Miller, 1986). The construction of the configurations of inter-organizational control draws on interviews completed with 17 French retailers in 2002/2003. The initial sampling aimed at selecting retailers in each retail channel category, included mail order, hyper- and super-markets, specialised chains, and department stores, with sales above Eu. 80 mn. Interviews were obtained with sourcing managers from 17 out of a resulting population of 30 retailers. The sourcing managers were the persons who were the most susceptible to give us precious information on different kinds of subjects. The wish for confidentiality, particularly important in the clothing industry, was another argument that led us to interview the sourcing managers: they were the only ones knowing what they were allowed to say or not say. 10 Five out of seventeen retailers interviewed belong to the top 10 category, including hypermarkets, discount chains and one mail order company. Others belong to the dynamic subsector of specialised chains, in the men’s wear, women’s wear, children’s wear or discount segments. Table 1 presents the firms characteristics: Table 1: sample characteristics ______________________________________________________________________ Firm Interviewed (retail category) Hypermarket Hypermarket Mail Order Group Discount Chain Discount Chain Discount Chain Men’s wear Chain Women’s wear Chain Women’s wear Chain Women’s wear Chain Women’s wear Chain Women’s wear Chain Women’s wear Chain Children’s wear Chain Children’s wear Chain Children’s wear Chain Ownership Date Private, family control Public subsidiary, public retail group Private, family control Private, family control Private, family control Subsidiary Public, management control Public, management control Public Public Public Private, family control Private, family control Public Private, management control Private January 2002 October 2002 January 2002 April 2003 February 2002 January 2002 April 2002 March 2002 February 2002 January 2002 April 2003 April 2003 May 2003 November 2003 March 2002 April 2002 March 2002 Clothing sales (Meuros) _ 1.500-2.000 2.000-2.500 1.000-1.500 600-700 180-200 500-600 450-500 350-400 200-250 250-300 1000-1500 450 150-200 100-150 50-100 Interviews with sourcing managers were conducted in a non-directive way. The main topics covered during discussions included: what we have called “demographic variables” referring to characteristics of retailers, their suppliers’ important characteristics, the nature of environmental pressures that existed on the retailers, in order to explain differences in terms of control practices, and of course, control in internal context as well as in inter-organizational relationships. The main important results of our study are presented in the next paragraph. 2.3 ) Results: the existence of different types of inter-organizational control modes and the upgrading opportunities associated to them First of all, we will describe the four great control modes we have been able to distinguish. We will then present the consequences of the four control modes in terms of industrial upgrading for the suppliers. Finally, we will tackle the impacts of the development of a dominant control mode implemented by French distributors. The existence of four great control modes A first analysis of the interviews made with sourcing managers, based on the use of the software of lexical analysis Alceste, allowed us to determine two great dimensions for segmenting our sample. These two dimensions are control formalism and time perspective in which the relationship is engaged. Four control configurations can be distinguished on this basis: “Clan”, “Rule”, “Market” and “Feel”. 11 Graph 1 presents these configurations. Graph 1: The four main classes of inter-organizational control Long term (partnership) Clan Rule Informal Formal Feel Market Short term The configuration of “Clan” refers to a control mode relying on trust between the retailer and its supplier and characterise six over our seventeen retailers studied. The configuration of “Rule” has been encountered in three cases and describes a control type between partners (in the sense that relationships have several years of existence) that is very formalized, the suppliers’ performances being measured with many criteria. The “Market” control is linked to the threatening of the end of the relationship in the case of bad results and has been observed in six cases. The configuration of “Feel” regroups two firms and refers to a great opportunism in the supply base shaping, with a strong importance given to prices. The creation of variables has then be a central element for the development of our knowledge of the configurations. Several variables have thus been defined in order to make configurations of inter-organizational control appear through the study of the links between all these variables. We have then created variables aimed at defining control practices and their determinants. Table 2 presents the variables (and the cuttings aimed at studying the links between variables) that have been constructed for the study of the links between the variables on the basis of the Fisher exact test of independence. This test is aimed at calculating an exact probability value for the relationship between two dichotomous variables, as found in a two by two crosstable. It works in exactly the same way as the Chi-square test for independence, being more accurate if there is a small value (less than five) in one of the cells, as it was the case for our study. 12 Table 2: Cuttings aimed at studying the links between variables _ Limit value X1 X2 n _ _ Variables Demographic variables Date of creation Starting date for international sourcing Number of outlets Turn-over Place of the firm before 80 / after 80 before 92 / after 92 < 200 / > or = 200 < 450 / > or = 450 Paris / Other places 9 10 8 9 11 8 7 9 8 6 17 17 17 17 17 Suppliers’ characteristics : Selection mode for the suppliers Average size of the suppliers Closeness of the suppliers Nature of the suppliers Definition of the suppliers’ performance Very formal/Less formal Small / Big Close / Far away Subcontractor /Supplier Price / Other or mix 9 9 7 7 9 8 8 10 10 8 17 17 17 17 17 Relational strategy and control : Position/supplier sharing Share of French fabrication Maximal production capacity used Indiff. Or fav. / Non fav. Weak (< 30%)/ Strong < 33% 11 11 7 6 6 10 17 17 17 Nature of environmental pressures : Nature of the most important shareholder Shareholders expectations Competitive stability on the market segment Price positioning NGO interventions Familial / Institutional Perpetuity / Return on inv. Stable / Unstable High or Medium / Low Yes / No 9 8 7 7 5 8 9 10 10 12 17 17 17 17 17 Internal structure : Buyer competence + Negotiation / + Product Integration of stylists in the sourcing structure Important / Weak 9 10 8 7 17 17 Internal control : Buyer formation Evaluation system Frequency of buyer evaluation 7 10 8 10 7 9 17 17 17 important / marginal Individual / Collective < 6 months The study of the links between the variables allowed us to highlight the most important characteristics that are associated to the four control modes. Tables 3 and 4 present these characteristics. Some of them result from the calculation of a statistical link (ST). The others, that are not linked from a statistical point of view, have been determined in an analytical way (AN), drawing on our knowledge and understanding of the French retail sector. 13 Table 3: The most important characteristics associated to the four control modes Market Rule Clan Flair Frequency of buyer evaluation ST High High Weak Weak Buyer formation ST Marginal Important Important Marginal Evaluation system AN Individual Collective Collective Individual « Relation and control – Buyer » Selection mode ST Formal Formal Non Formal Non Formal Performance definition ST Price Other or mix Other or mix Price Suppliers’ proximity ST Far away Far away Close Close Suppliers’ size AN Big Big Small Small « Relation and control – Supplier » Competitive stability ST Unstable Stable Stable Unstable Price positioning AN Low prices Low prices High prices High prices Shareholders’ nature AN Institutional Institutional Familial Familial Outlets number (size) ST > 200 > 200 < 200 < 200 Beginning of int. sourcing AN Before 92 Before 92 After 92 After 92 « explaining factors » Table 3 puts into evidence the three main dimensions along which differences have emerged between the different control modes. The first dimension concerns control that is set on the buyers themselves. This control has been described as being coherent with the control observable in the context of inter-organizational relationships (Poissonnier, 2005). The second dimension reveals differences in terms of inter-organizational control. More accurately, formalization of the selection, performance definition and especially the role of price in this selection, suppliers’ proximity revealing the degree of adoption of lean-retailing principles and suppliers’ size are the most important variables allowing a segmentation of the firms investigated on the basis of the dominant control mode they develop. The third dimension presents factors explaining differences in control practices both in intra- and interorganizational contexts. The variables presented in table 3 reveal the importance of ownership structure (“shareholders’ nature”), factors linked to competition (competitive stability, price positioning) and “demographics factors” (outlet number and experience in international sourcing). Table 4 provides another highlighting of the main differences between the four types of control chains, being more accurate on coherence between internal and external control and control dynamic. It also provides information about the emblematic type of firm that are more likely to develop each type of control. 14 Table 4: Main differences between the four types of control chains Market Rule Clan Feel Internal – external coherence Strong Strong Very Strong Weak Previous conditions observed Institutional investors, Low prices High social pressures (ethics) Director’s culture (family firm) Central role of the buying director Control dynamic Strong , towards Rule Stable Strong, towards Rule Very strong Emblematic type of firm Low prices chain Hypermarket High quality chain New chain, low or middle quality chain. Our first result is linked to the confirmation of the existence of several types of interorganizational controls. This result is original considering the abundant literature on interorganizational control. Rule, Market and Clan have been largely described as interorganizational control types. Celly & Frazier (1996) point out the existence of two great kinds of coordination efforts in channel relationships: outcome-based and behaviour-based which are very similar to what we have called “Market” and “Rule”. Several authors have described a control mode close to what we have called “Clan”, referring to culture (Ray, 1986) or trust (Adler, 2001). Markets, bureaucracies and clans, as they are described by Ouchi (1980) are also very close to our three main control modes. The originality of our findings lays in the presentation of a fourth control modes, called “Feel”. This reveal the existence of a great social embeddedness of the industry in France in which retailers traditionally develop social relationships. The importance of this specificity tend to decrease while rationalisation of sourcing practices develops. We have thus noted a very strong dynamic of evolution of these control modes. Consequences of the four control modes on upgrading opportunities The distinction between price- (that are associated to Market and Feel as control modes) and quality-driven chain (associated to Rule and Clan) highlights the question of the consequences of the implementation of each control modes on upgrading opportunities for the suppliers. As Schmitz & Knorringa (2000) argues, the more product quality matters, the greater the buyers’ interest in upgrading the producers. Buyers more interested in quality are more aware of the cost of changing partners for the sake of price advantages. They prefer indeed stable relations allowing suppliers to improve the quality of their products. “Market” and “Feel”, because of short time perspective, do not allow important upgrading opportunities which needs time and stable relationships. They engage however suppliers in reducing costs in order to propose a price as lowest as possible. But even if suppliers succeed in this action, the stability of the relationship is not sure because of the fact that a small change rate variation can largely modify sourcing portfolios, the apparel industry being an industry in which comparative advantages as defined by Ricardo are often more important than competitive advantages as defined by Porter. Pressures forcing suppliers to focus on achieving greater economies of scale imply greater specialization and narrows the range of 15 opportunities for learning that are given to suppliers. Upgrading opportunities that are given to suppliers are then more and more threatened “Clan” and “Rule” are the control modes allowing the best upgrading opportunities for suppliers. In addition to stable relationships, Rule rely on the transmission of requirements engaging suppliers in learning by doing. “Clan” create a more partnership climate favouring initiatives and innovation from suppliers. Retailers adopting this control mode are waiting suppliers to develop innovative propositions, for instance by offering design services to their clients. It is then possible to distinguish two different forms of learning opportunities that are given to suppliers depending on the control mode chosen by their retailers. Rule give rise to narrow but more structured learning experiences while “Clan” seems to favour broader but more diffuse learning experiences that are more dependant to the supplier’s own innovative orientation and capacities. In a way, suppliers can learn more while controlled through “Clan” if they are “pro-active” in their learning process while “Rule” allows a more “re-active” learning process. The type of upgrading favoured by the development of “Rule” Traditionally, the dominant control mode implemented by French retailers was the “Clan” (Poissonnier, 2005). Our study shows that the more developing control mode is “Rule”. This evolution have strong impacts on the upgrading opportunities that are given to suppliers. The positive evolution for suppliers is linked to the creation of partnerships, which can be explained by the necessity for retailers to wait for a return on investment after a longer selection process. This development of “Rule” is both cause and consequence of the implementation of a core-periphery model. More and more, lead-firms co-ordinate complex production networks by differentiating between core suppliers with whom they maintain stable relationships and peripheral suppliers operating on the basis of market-based, shortterm links with their clients (Palpacuer, 1997, 2000). This is coherent with the findings of Dyer & al. (1998) who presented supplier segmentation as the next “best practice” in supply chain management. In this situation, it becomes more and more important for suppliers to enter the core suppliers if they are to succeed in upgrading. Another important finding is that retailers always prefer helping their suppliers in upgrading within the sphere of production rather than into non-production activities such as design and marketing. The reason is clear and is linked to the fact that marketing and design are part of the buyers’ own guarded core competence as Schmitz & Knorringa (2000) noted. Sustainable development is then still (and even more) allowed but concerns only a few suppliers defined as core-suppliers while the others experience more and more difficulties to take their place in international business. Conclusion The main goal of our research was to identify the conditions under which trade based growth could become a vehicle for genuine industrial upgrading and sustainable development for suppliers’ countries. We have addressed this question using a global commodity chains framework. According to Gereffi (1999), the linkage to a GCC is a necessary condition for learning, and then upgrading, to occur. Our literature review confirmed that trade-based learning mechanisms have strong effects on differences in industrial upgrading between CEE economies (Hotopp & al., 2005). 16 In the first time, the construction of a taxonomy of inter-organizational control modes was made to take the diversity of practices implemented by French retailers into account. Four great control modes have been pointed out: “Market”, “Rule”, “Clan” and “Feel”. We have then studied the characteristics of these four control modes and the dynamic of their evolution, as well as their most important factors of explanation. It enabled us to present an accurate view of the French retailers’ practices in terms of inter-organizational control and to conclude on the upgrading opportunities offered to their suppliers. Several points should receive a greater attention. First of all, we have pointed out the growing influence of ownership structures and NGO actions on the functioning of GCCs. Institutional investors tend to favour the setting up of “Market” control. Campaigns from development organisations such as the American “Global Watch” or the European “Clean Clothes Campaign” have then proved a potent force for change, particularly to tackle “sweatshop” conditions in garment production. Jones (1999) explains that this kind of pressures are to increase social responsibility. These new pressures favour “Rule” based control, because retailers can not take risks any more in terms of social considerations. Doing this, they offer new upgrading opportunities to their suppliers as we have explained. In spite of the dominant position of retailers, suppliers could then receive advises allowing a strengthening of their position. Gereffi & Tam (1998) explain that the “ecology” of a commodity chain is dynamic, being dependent on the strategic actions of firms and groups of firms. According to Gereffi (1996, 1999), commodity chains are largely “buyer-driven” in the apparel industry. We agree these conception that gives the central role to retailers in generating or not the conditions for sustainable development of their suppliers. However, several examples of responses used by suppliers to improve their conditions can be mentioned. Choi & al. (2002) explain how horizontal relationships between suppliers are determinant for the strengthening of the suppliers’ role in the shaping of their relationships with retailers. This idea is confirmed by Cossentino & al. (1996), showing how industrial districts in Italy give power to participating producers. The growing concentration of buying power in France, like in most developed countries, and the tendency of large retailers to establish fewer but closer relationships with apparel manufacturers has increased competition among apparel suppliers all over the world (Kessler, 1999). But if they are to succeed in developing, suppliers have to be aware of the necessity to develop horizontal as well as vertical relationships. In a way, the answer is always interorganizational fostering the sharing of knowledge and enabling the raising of the quality of production to world class standards which is a key determinant for success. Our findings however confirm those of Schmitz & Knorringa (2000) arguing that suppliers face greater obstacles in upgrading through developing design and marketing competences than in production upgrading. The situation of the apparel industry we have described, presenting the French retailers’ sourcing and inter-organizational control practices is probably not a-typical for labour intensive export sectors in developing countries. Through our case study, we have tackled the question of the trade’s potential for lifting broad swatches of people out of poverty. In so doing, we have studied new challenges facing producers in developing countries in our more and more globalized world. The question of the answers that could be given to those new challenges remains an open and interesting question. 17 Bibliography Abernathy F., Dunlop J., Hammond J. & Weil D. (1999), A stitch in time: lean retailing and the transformation of manufacturing, New York, Oxford University Press. Adler P. S. (2001), Market, Hierarchy and Trust: The Knowledge Economy and the Future of Capitalism, Organization Science, vol. 12, p. 215-234. Agndal H. & Axelsson B. (2002), Internationalisation of the Firm – The Influence of Relationship Sediments, Proceedings of the Inaugural Meeting of the IMP Group Asia on Culture and Collaboration in Distribution Networks, Perth, 11-13 December. Alguire M. S., Frear C. R. & Metcalf L. E. (1994), An Examination of the Determinants of Global Sourcing, The Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 9, n° 2, p. 62-74. Amin A. (1994), Post Fordism, Blackwell. Appelbaum R. & Gereffi G. (1994), Power and profits in the apparel commodity chain, in Bonacich E., Cheng L., Chinchilla N., Hamilton N. & Ong P. (Eds.), Global production: the apparel industry in the Pacific Rim, p. 42-62, Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Araujo L., Dubois A. & Gadde L. E. (1999), Managing Interfaces with Suppliers, Industrial Marketing Management, vol. 28, n° 5, p. 497-506. Arnold U. (1989), Global Sourcing: An Indispensable Element in Worldwide Competition, Management International Review, 29, n° 4, p. 14-28. Arrow K. (1962), The Economic Implications of Learning by Doing, Review of Economic Studies, 29, June, p. 155-173. Bachman S. L. (2000), The Political Economy of Child Labor and its Impacts on International Business, Business Economics, 35, 3, p. 30-41. Bailey T. (1993), Organizational innovation in the apparel industry, Industrial Relations, vol. 32, n° 1, p. 30-48. Bair J. & Gereffi G. (2002), Nafta and the apparel commodity chain: Corporate strategies, interfirm networks, and industrial upgrading, in Gereffi G., Spener D., & Bair J. (Eds), Free trade and uneven development: The North American apparel industry after Nafta, p. 32-52, Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Bensaou B. M. (1999), Portfolios of buyer-supplier relationships, Sloan Management Review, vol. 40, n° 4, Summer, p. 35-44. Birnbirg J. G. (1998), Control in interfirm co-operative relationships, Journal of Management Studies, vol. 35, Issue 4, Juillet 1998, p. 421-428. Black B. (2001), National culture and industrial relations and pay structures, Labour, vol. 15, n° 2, P. 257-277. Celly K. S. & Frazier G. L. (1996), Outcome-Based and Behavior-Based Coordination Efforts in Channel Relationships, Journal of Marketing Research, vol. 33, May, p. 200-210. Chacon F. (2000), International Trade in Textiles and Garments : Global Restructuring of the Sources of Supply in the United States in the 1990s, Integration and Trade, Mai-Août 2000, p. 17-45. Cherret K. (1994), Gaining Competitive Advantage through Partnering, Australian Journal of Public Finance, vol. 53, n° 1. Cho J. & Kang J. ( 2001), Benefits and Challenges of Global Sourcing: Perceptions of US Apparel Retail Firms, International Marketing Review, vol. 18, n° 5, p. 542-561. 18 Choi T. Y., Wu Z., Ellram L. & Koka B. R. (2002), Supplier-supplier relationships and their implications for buyer-supplier relationships, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, Mai 2002, p. 119-130. Clark K. (2002), Making global sourcing right, Chain Store Age, vol. 78, Iss. 12, p. 122-124. Cossentino F., Pyke F. & Sengenberger W. (1996), Local and regional response to global pressure: the case of Italy and its industrial districts, Research Series 103, Geneva, International Institute for Labour Studies. Cox A., Ireland P., Lonsdale C., Sanderson J. & Watson G. (2001), Supply Chains, Markets and Power: mapping buyer and supplier power regions, Routledge, London. Dekker H. C. (2004), Control of inter-organizational relationships: evidence on appropriation concerns and coordination requirements, Accounting Organization and Society, vol. 29, p. 27-49. Dicken P. (1998), Global Shift: Transforming the World Economy, 3 rd edn, New York and London: The Guilford Press. Dickerson K. G. (1991), Textiles and Apparel in the International Economy, New York : Macmillan Publishing Company. Donada C. (1997), Fournisseurs : pour déjouer les pièges du partenariat, Revue Française de Gestion, JuinJuillet-Août 1997, p. 94-105. Droge C. & Germain R. (1997), Effects of just-in-time purchasing relationships on organizational design, purchasing department configuration, and firm performance, Industrial Marketing Management, n° 26, p. 115-125. Dussel E., Duran C. R. & Piore M. J. (1997), Learning and the limits of foreign partners as teachers’, paper presented at “Global Production, Regional Responses, and Local Jobs : Challenges and Opportunities in the North American Apparel Industry”, Duke University, 7-8 November. Dyer J. H. & Chu W. (2003), The Role of Trustworthiness in Reducing Transaction Costs and Improving Performance: Empirical Evidence From the United States, Japan and Korea, Organization Science, vol. 14, n° 1, p. 57-68. Dyer J. H., Cho D. S. & Chu W. (1998), Strategic supplier segmentation: The next “best practice” in supply chain management, California Management Review, vol. 40, n° 2, p. 57-77. Ernst D. (2000), Global production networks and the changing geography of innovation systems : implications for developing countries, East-West Center Working Paper, 9, Honolulu: East-West Center. Firoz N. M. & Ammaturo C. R. (2002), Sweatshop labour practices: the bottom line to bring change to the new millennium case of the apparel industry, Humanomics, Patrington, vol. 18, Issue ½, p. 29-45. Ford D. & Hakansson H. (2002), How should companies interact in business networks ?, Journal of Business Research, 55, p. 133-139. Ford D. (1980), The development of buyer-seller relationships in industrial market, European Journal of Marketing, vol 14, n° 5/6, p. 339-354. Ganesan S. (1994), Determinants of long-term orientation in buyer-seller relationships, Journal of Marketing, vol. 58, n° 2, p. 1-19. Gereffi G. (1999), International trade and industrial upgrading in the apparel commodity chain, Journal of International Economics, n°48, p. 37-70. Gereffi G. (1996), Global Commodity Chains: New Forms of Coordination and Control Among Nations and Firms in International Industries, Competition and Change, vol. 4, p. 427-439. 19 Gereffi G. (1994), The organization of buyer-driven global commodity chains: How US retailers shape overseas production networks, In Gereffi G. & Korzeniewicz M. (Eds.), Commodity Chains and Global Capitalism, Praeger Publishers. Gereffi G & Tam T. (1998), Industrial upgrading through organizational chains: dynamics of rents, learning by doing, and mobility in the global economy, paper presented at the 93rd Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association, San Fransisco, California, 21-25 August. Gibbon P. (2003), The African Growth and Opportunity Act and the Global Commodity Chain for Clothing, World Development, vol. 31, n° 11, p. 1809-1827. Gibbon P. (2002), At the cutting edge ? Financialisation and UK clothing retailers’ global sourcing patterns and practices, Competition and Change, 6, p. 289-308. Gibbon P. (2001), At the Cutting Edge : UK Clothing Retailers and Global Sourcing, Center for Development Research Working Papers, August 2001, Copenhagen, p. 1-36. Gibbon P. (2000), “Back to the Basics” through Delocalisation: The Mauritian Garment Industry at the End of the Twentieth Century, Center for Development Research Working Papers, October 2000, Copenhague, p. 1-66. Gilbert F. W., Young J. A. & O’Neal C. R. (1994), Buyer-seller relationships in just-in-time purchasing environments, Journal of Business Research, vol. 29, February 1994, p. 111-120. Hakansson H., Avila V. & Pedersen A-C (1999), Learning in Networks, Industrial Marketing Management, vol. 28, n° 5, p. 443-452. Harrison A. & Scorse J. (2006), Improving the Conditions of Workers? Minimum Wage Legislation and AntiSweatshop Activism, California Management Review, vol. 48, n° 2, winter. Heide J. B. (1994), Interorganizational governance in marketing channels, Journal of Marketing, vol. 58, January 1994, p. 71-86. Henderson J., Dicken P., Hess M., Coe N. & Yeung H. (2002), Global production networks and the analysis of economic development, Review of International Political Economy, 9, 3, p. 436-464. Hopkins J. K. & Wallerstein I. (1994), Commodity Chains: Construct and Research, in Gereffi G. & Korzeniewicz M. (eds.) Commodity Chains and Global Capitalism, Westport, CT: Praeger. Hopwood A. (1996), Looking across rather up and down: on the need to explore the lateral processing of information, Accounting Organizations and Society, vol. 21, p. 589-590. Hotopp U., Radosevic S. & Bishop K. ( 2005), Trade and Industrial Upgrading in Countries of Central and Eastern Europe, Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, vol. 41, n° 4, July-August 2005, p. 20-37. Humphrey J. & Schmitz H. (2000), Governance and Upgrading: Linking Industrial Cluster and Global Value Chain Research, IDS Working Paper, n° 120, Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex, Brigthon. Jones M. T. (1999), The institutional determinants of social responsibility, Journal of Business Ethics, Jun 99, vol. 20, Issue 2, p. 163-179. Kalika M., Guilloux V. & Laval F. (1998), Structuration des entreprises et relations d’affaires internationales, Sciences de Gestion, XXXII, n° 8, 9, Septembre 1998. Kaplinsky R. (2000), Globalization and unequalization : what can be learned from value chain analysis ?, Journal of Development Studies, 37, 2, p. 117-146. 20 Kessler J. A. (1999), The North American Free Trade Agreement, emerging apparel production networks and industrial upgrading : the southern California/Mexico connection, Review of International Political Economy, 6, 4, Winter 1999, p. 565-608. Lane C. & Bachman R. (1996), The social constitution of trust: supplier relations in Britain and Germany, Organization Studies, 17/3, p. 365-395. Lazonick W. & O’Sullivan M. (2000), Maximizing shareholder value : A new ideology for corporate governance, Economy and Society, 29, 1, p. 13-35. Miller D. (1986), Configurations of strategy and structure : toward a synthesis, Strategic Management Journal, vol. 7, n° 3, p. 233-249. Mohr D. C. & Spekman R. E. (1994), Characteristics of partnership success: partnership attributes, communication behavior, and conflict resolution techniques, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 15, p. 135-152. Monczka R. M., Callahan T. J. & Nichols E. L. (1995), Predictors of relationships among buying and supplying firms, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, vol. 25, n° 10, p. 45-59. Monczka R. M. & Trecha S. J. (1988), Cost-Based Supplier Performance Evaluation, Journal of Purchasing & Materials Management, Spring, vol. 24, issue 1, p. 2-7. Otley D. (1994), Management control in contemporary organizations: toward a wider framework, Management Accounting Research, vol. 5, p. 289-299. Ouchi W. G. (1980), Markets, Bureaucracies and Clans, Administrative Science Quarterly, March 1980, vol. 25, p. 129-141. Palpacuer F., Gibbon P. & Thomsen L. (2005), New Challenges for Developing Country Suppliers in Global Clothing Chains: A Comparative European Perspective, World Development, vol. 33, n° 3, p. 409-430. Palpacuer F. (2004), The global sourcing patterns of French clothing retailers: Determinants and implications for suppliers’ industrial upgrading, Workshop and Conference, University of North Carolina: Chapel Hill, October, 15-16th. Palpacuer F. & Parisotto A. (2003), Global production and local jobs: Can global production networks be used as levers for local development? Global Networks, 3, 2, p. 97-120. Palpacuer F. & Poissonnier H. (2003), The global sourcing networks of french clothing retailers : organizational patterns and opportunities for supliers’industrial upgrading, Working paper, Danish Institure for International Studies, Center for Development Research, Copenhagen November 2003, 32p. Palpacuer F. (2000), Competence-based strategies and global production networks: A discussion of current changes and their implications for employment, Competition and Change, 4, p. 353-400. Palpacuer F. (1997), Development of core-periphery forms of organizations: some lessons from the New York garment industry, Discussion papers, International Institute for Labour Studies, 31 p. Poissonnier H. (2005), Proposition d’un cadre d’analyse du contrôle inter-organisationnel fondé sur la chaîne de contrôle : une étude centrée sur la filière THD, Thèse de Doctorat soutenue le 2 décembre 2005, Université Montpellier II. Ray C. A. (1986), Corporate Culture : The Last Frontier of Control ?, The Journal of Management Studies, Mai 1986, p. 287-298. Ring P. S. & Van de Ven A. H. (1994), Developmental processes of cooperative interorganizational relationships, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 19, n° 1, p. 90-118. 21 Ring P. S. & Van de Ven A. H. (1992), Structuring cooperative relationships between organizations, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 13, p. 483-498. Rollins R. P., Porter K. & Little D. (2002), Modelling the changing apparel supply chain, International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, vol. 15, n° 2, p. 140-156. Schmitz H. & Knorringa P. (2000), Learning from Global Buyers, The Journal of Development Studies, vol. 37, n° 2, Décembre 2000, p. 177-203. Sorensen J.-E. (2001), Trade, Environment and Sustainable Development, World Summit for Sustainable Development, United Nations University Centre, 3-4 September. Trent R. J. & Monczka R. M. (2002), Pursuing competitive advantage through integrated global sourcing, Academy of Management Executive, May 2002, vol. 16, issue 2, p. 66-80. Van de Ven A.H. (1976), On the Nature, Formation and Maintenance of Relationships among Organizations, Academy of Management Review, vol. 1, October, p. 24-36. Van der Meer – Kooistra J. & Vosselman G. J. (2000), Management control of interfirm transactional relationships: the case of industrial renovation and maintenance, Accounting, Organizations and Society, vol. 25, p. 51-77. Watanabe S. (1978), Technological Linkages between Formal and Informal Sectors of Manufacturing Industry, Working Paper, n° 34, Technology and Employment Programme, WEP 2-22, ILO, Geneva. Watanabe S. (1971), Subcontracting, Industrialisation and Employment Creation, International Labour Review, vol. 104, n° 1 & 2. Whitley R. (1999), Divergent capitalisms : the social structuring and change of business systems, New York, Oxford University Press. Whitley R. (1996), Business Systems and Global Commodity Chains : Competing or Complementary Forms of Economic Organisation?, Competition & Change, 1996 Vol. 1, p. 411-425. Zaheer A., Mc Evily B. & Perrone V. (1998), Does trust matter? Exloring the effects of interorganizational and interpersonal trust on performance, Organization Science, vol. 9, n° 2, March-April, p. 141-159. 22