View/Open

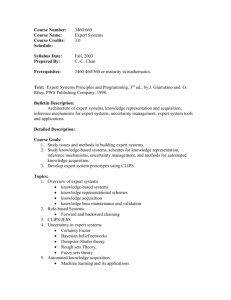

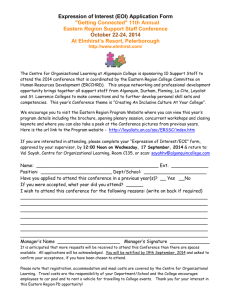

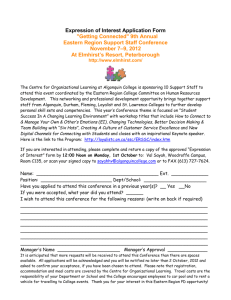

advertisement