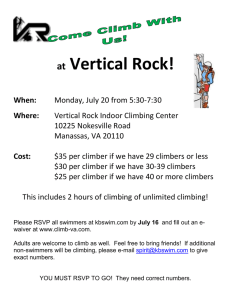

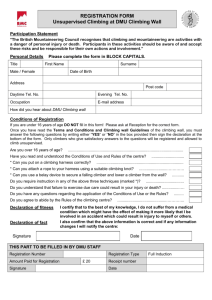

Stone Age Climbing Gym 2010 Advertisement

advertisement