Getting Started Rock Climbing

advertisement

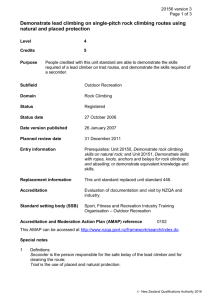

Getting Started Rock Climbing For physical fitness, fun and, yes, adrenaline, nothing beats rock climbing. Despite its daredevil reputation, rock climbing can be enjoyed safely by any reasonably fit person with proper instruction and equipment. But keep in mind that professional instruction is essential for any beginner—especially if you are heading outdoors. It takes more than reading an article and viewing videos to make you a climber! Indoor Sport Climbing This can be at a climbing gym, sports club or even a home climbing wall. Indoor walls have artificial hand and foot holds placed in sequence to create routes of varying difficulty. Route setters can move holds easily, creating an endless number of fresh, new climbs. Routes can be low-angled, vertical or overhanging, with fun curves, caves and roofs. Indoor sport climbing offers a great way for beginners to get started: A gym is often convenient—there are hundreds of dedicated climbing gyms across the U.S. and many more climbing walls in local athletic clubs. It offers a safe, controlled environment to practice. It's not dependent on the weather. You can climb in areas where no outdoor climbing sites are available. Handholds and footholds are clearly visible. It allows you to try the sport with rented gear before investing in your own. There are routes for all levels of ability. If you have a fear of heights, indoor climbing can be less daunting than climbing outside. Beginner or expert, rock climbing gets you fit, fast. No matter what your level of expertise, climbing the walls at an indoor gym makes you stronger, leaner and more graceful. Outdoor Rock Climbing Outdoor climbing is not as predictable as indoor climbing, but it comes with a near-guarantee of beautiful scenery, great exercise and unbeatable camaraderie. It can be divided into several categories. Bouldering: This requires the least amount of time and equipment. Basically, bouldering is close-to-the-ground climbing without a rope, going only as high as you can jump off without risking serious injury. Beginners can traverse (move along the rock horizontally, parallel to the ground), thus working on strength and movement without going so high as to risk a serious fall. For bouldering, all you need are climbing shoes, a crash pad (to cushion your landing if you jump or fall off the rock) and perhaps a chalk bag. You can also bring along friends to "spot" you. Sport climbing: Climbing got easier and safer in the 1990s with the addition of pre-placed bolts. This "clip-and-go" style of climbing allows the leader to progress upwards without the worry of placing protection. A "bolted" climb requires only a rope, quickdraws (described below), shoes and a chalk bag. It refers to routes that have permanent or pre-placed anchors and protection where you can attach your rope. Traditional ("trad") climbing: Trad climbing is true adventure. A trad route is one that has few permanent anchors. The lead climber protects himself from a catastrophic fall by placing protection, nuts or camming devices, into fissures in the rock. The second climber removes the protection, and it's then placed again for further pitches. Carabiners and quickdraws are used to connect the rope into the protection. Other types of climbing: such as soloing, ice climbing or big-wall climbing; are outside the scope of this article. Climbing Route Ratings Routes are rated by the hardest move on the route. In the U.S., the Yosemite Decimal Rating System is most commonly used to classify climbing difficulty. Climbing Route Classifications Class 1 Walking an established flat, easy trail. Class 2 Hiking a steep incline, scrambling, maybe using your hands. Class 3 Climbing steep a hillside, moderate exposure, a rope may be carried but not used, and hands are used in climbing. A short fall could be possible. Class 4 It is steeper yet, exposed and most people use a rope due to the potential of long falls. Class 5 Climbing is technical and belayed roping with protection is required. It is not for a novice. Any fall from a Class 5 could be fatal. Class 5 sub-categories 5.1-5.4 Easy Climbing a steep section that has large hand and foot holds. 5.5-5.8 Intermediate Small foot and handholds. Strength and rock climbing skills required. Low to vertical terrain. 5.9-5.10 Hard Not for beginners. Technical, vertical and may have overhangs. Rock shoes required. 5.11-5.12 Hard to Difficult Not for beginners. Technical, vertical and may have overhangs. Rock shoes required. 5.13-5.15 Very Difficult Not for beginners. Technical, vertical and may have overhangs. Rock shoes required. To further define a route's difficulty, a subclassification system of letters (a, b, c or d) is used for climbs 5.9 and higher. For instance, a route rated 5.10a is easier than one rated 5.10d. Some guidebooks use a plus (+) or minus (-) rating instead of the letters. Basic Climbing Gear Here's an overview of indispensable climbing gear. If you start out at a gym or climb with a guide, all the necessary equipment is usually provided. But eventually you'll want to get your own. Tip: Be safe. Always inspect your gear before climbing—whether you own it or rent it. While climbing equipment has some of the most stringent manufacturing safety standards in the world, frequent use inevitably results in some wear and tear. The advantage of buying your own gear is that you know its history. Climbing Harness Unless you are bouldering, you need a climbing harness. A harness consists of 2 basic parts: Waistbelt: This sits over the hips and must fit snugly. Leg loops: One loop goes around each leg. Many harnesses conveniently offer adjustable or removable leg loops. Your harness allows you to tie into the rope safely and efficiently. All harnesses have a front tie-in point designed specifically for threading the rope and tying in. Generally the tie-in point is different than the dedicated belay loop. Buckling your harness correctly is essential for safety. Fit tip: Test if the waistbelt is tight enough by opening your hand and slipping it between your body and the harness. Then make a fist. If the harness is fitting properly, you should not be able to pull your fist back out. If it slips out, the waistbelt is too loose. The right harness model depends on the type of climbing you plan on doing. There are multipurpose, alpine, big wall and competition varieties of harnesses. Rock Climbing Shoes Climbing shoes protect your feet while providing the friction you need to grip footholds. Most styles are quite versatile, but your climbing ability and where you climb are both factors in choosing the correct shoe. Rock shoes should fit snugly but not painfully tight. The general rule is that the harder you climb, the closer-fitting the shoe should be. Tip: Because rock shoes are so form-fitting, they aren't comfortable for walking long distances. If the hike from your car to the base of your climbing area involves some scrambling on rock slabs, wear "approach shoes." These are lightweight, durable shoes with high-friction rubber soles and rands. Trail or road approaches can be handled by lightweight hiking boots or even running shoes. Climbing shoes are for climbing only— change into them once you reach the start of the climb. Climbing Helmet When climbing outdoors, you should always wear a helmet made specifically for climbing. Climbing helmets are designed to cushion your head from falling rock and debris, as well as provide protection in the case of a fall. They are generally not worn in a climbing gym since it's a controlled environment. A helmet should feel comfortable, fit snugly but not too tight and sit flat on your head. Helmets have a hard, durable protective shell and an internal strapping system that consists of the harness, headband and chin strap. The internal harness keeps the helmet in the proper position on top of your head. The chin strap adds additional security—especially if you accidently become inverted. Many helmets are adjustable, so you can dial in a custom fit. Carabiners These strong, light metal rings with spring-loaded gates connect the climbing rope to pieces of climbing protection such as bolts, nuts and camming devices. They are also used to make quickdraws and to rack (attach) your gear to your gear slings. You need at least a dozen carabiners on most climbs. They come in a few basic shapes: Oval: A basic 'biner that can be used for just about any climbing situation. D-shape: Stronger carabiners because the D shape can withstand more outward force. Asymmetrical D-shape: Smaller at one end to reduce weight, and the shape tends to push the rope to the solid side of the carabiner. Carabiners also come in different gate styles: Straight: Spring-loaded, opens easily when pushed, rotates closed. Bent: Designed for easy clipping, but should not be used for protection. Locking: Used when a single carabiner is needed and for extra protection, as in belaying. Wire: Uses a loop of stainless-steel wire for a gate. Belay Device This is used to control the rope in order to secure a climber's progress. Used correctly, a belay device can be used to can catch a fall, lower a climber, play the rope out as the climber advances or reel in the rope to provide tension. There are several styles—tubular, self-braking and figure-8. Quickdraws A quickdraw consists of 2 carabiners connected by a sling (also called a runner). While you can fashion your own from webbing and carabiners, pre-stitched 'draws greatly increase speed and efficiency when clipping bolts, making them essential for sport climbing. Pre-stitched quickdraws are convenient for clipping onto bolts, ropes and gear. Climbing Ropes Brain excluded, no piece of equipment is more important to a climber than the rope. You can fall up to 50 feet in about 2 seconds, A climbing rope is your lifeline and a very specialized piece of gear. There are different qualities of rope, and where and what you are climbing will determine which rope is best for you. The 2 basic categories of rope: Dynamic: This is a rock climbing rope because it has elasticity worked into it. It's designed to absorb the energy of a fall—even though the force of a fall can be very large. Static: This is a relatively stiff rope that, unlike dynamic rope, does not have much elasticity. It is used for rappelling and rescues. Care tip: Protect your rope. Don't step on it. It's a good idea to use a rope bag to keep the rope off of the dirt. Store it neatly coiled in a clean, cool place away from chemicals and out of the sun (as you should with all climbing gear). Always check ropes and slings for cuts and abrasion before you climb. Climbing Protection Often simply called "pro," these devices are used in traditional climbing to secure a climbing rope to the rock. Placed properly in a crack or hole, they prevent a climber from falling any significant distance. Types of protection include cams, chocks and nuts, often referred to by trade names such as Stoppers, Hexcentrics or Friends. In an earlier climbing era, pitons were used most often. There are 2 basic types of pro, both of which come in a variety of sizes: Active: These have movable parts, such as a spring-loaded camming device (SLCD) that can adapt to fit a variety of cracks. Passive: These are made from a single piece of metal and have no movable parts, such as a Hexcentric. A beginning climber is most likely to start out top-roping at a climbing gym or outdoors on routes with permanent anchors on top. Learning to set anchors and place protection adds an exciting dimension to the sport and makes you a safer, more wellrounded climber. Other Gear Considerations Clothing: Wear clothing that is not restrictive and won't get in the way of you or the rope. It should breathe and manage moisture so you stay warm or cool while climbing. If you climb outdoors, always plan for changing conditions. Chalk: Just like gymnasts, climbers use chalk to improve their grip. Chalk absorbs perspiration on your hands. Chalk is carried in a small pouch slung from your waist by a lightweight belt. Crash pads: A must for bouldering, these dense foam pads are placed under the climber to cushion a fall or jump. Belaying Belaying—the technique used to stop another climber's fall—is an essential part of climbing. It is a specific method of moving rope through a belay device as your climbing partner ascends, letting it out when needed and braking if they fall. Belaying is one of the first things a novice climber should learn. The belayer is positioned below the climber (or above on a multipitch or walk-off route). The belay device is attached to the belayer's harness, with the rope winding through the device and then extending to the other climber. The belay device and rope are both attached to a locking carabiner. Tip: If you are belaying, avoid standing directly under the climber in case of falling rock (or dropped gear). The belayer puts one hand on the rope strand going up and the other hand on the strand going down. The brake hand is kept in a closed fist. As the climber ascends, slack is created in the rope. The belayer's job is to keep pulling in rope to eliminate any slack. Be a safe climber and master this fundamental before your partner leaves the ground! And always climb with someone who is confident in his or her own belay skills. Tip: Always pay attention to the climber you are belaying. Be alert and ready for a fall. Communication between belayer and climber is a key to safety and teamwork. Top-roping Top-roped climbing is when your rope is anchored from above. You are belayed by your partner who is usually standing below you at the base of the pitch or, less commonly, above you at the top of the pitch. When top-roping single-pitch climbs from the ground, the belayer holds one end of the rope and pulls in slack, keeping the rope taunt. The rope goes up through the anchor on top of the climb, then loops back to a secure knot tied to your harness. Top-roping allows beginners to learn without distractions. Without the task of clipping bolts or placing protection, you can focus on movement and using your feet and hands more efficiently. Top-roping is also a great way for advanced climbers to push their climbing limits or practice a set of moves before leading a climb. The climber attaches to the rope using a follow-through figure-8 knot with a simple overhand knot to keep any excess rope (the "tail") out of the way. Before starting the climb, partners should always double-check each other's knots, harness buckles and locking 'biners to ensure the system is perfect. It is important to communicate with each other when top-roping. Climbers rely on a checklist of commands for safety. Here's a typical scenario: Climber: "Belay on?" Belayer: "Belay is on." Climber: "Climbing." Belayer: "Climb on." Climber: "Take." Belayer: "Show me your hands." Climber: "Ready to lower." Belayer: "OK, lower." Climber: "Off belay." Belayer: "Belay off." Basic Climbing Technique There are many different climbing techniques. The most important rule is to climb safely by getting competent or professional instruction beforehand. As a novice, you may think climbing requires really strong arms and fingers. In fact, the real power in climbing comes from your legs. If you keep the weight on your feet instead of gripping and holding yourself with your arms, you won't tire as quickly. Other good practices: Keep your heels lower than your toes. Use the friction of your climbing shoes. Use your hands for balance. Drop your heels to help put weight on your feet. Move fluidly. Safety Tips Be careful and alert. Use the right kind of equipment. Seek professional instruction. Take a class, hire a guide or go with an experienced climber. Don't overexert yourself. Stay within your limits. If you're injured, wait until you're healed before climbing again. Avoid areas where there is a lot of loose rock. If you displace a rock or drop a piece of equipment, yell "Rock!" to warn others. If someone else yells "rock," don't look up. You don't want to get smacked in the face. Test foot and handholds before using them. Don't climb in bad weather. Watch out for birds, snakes or other critters residing in handholds. Always safety-check your harness, rope, belay device and knots before climbing. Wear a helmet when climbing. Know and trust your belayer.