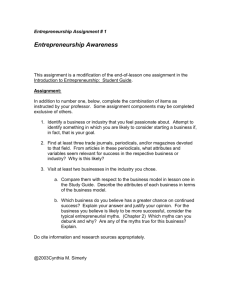

ASSESSING ENTREPRENEURIAL CHARACTERISTICS

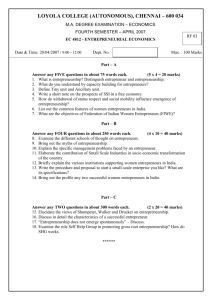

advertisement