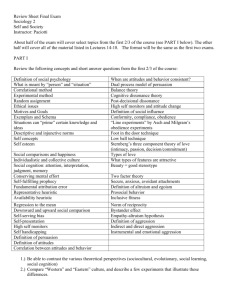

Program - Mississippi State University

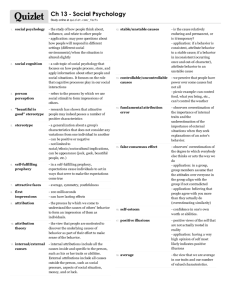

advertisement