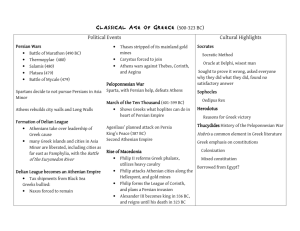

Assess the reasons for the victory of the Greeks in the Persian War

advertisement

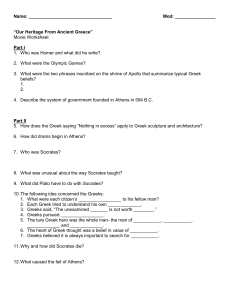

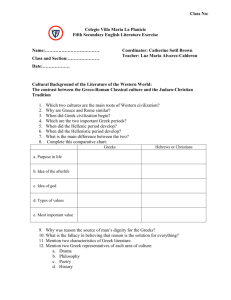

Assess the reasons for the victory of the Greeks in the Persian War 480-479B.C.E Herodotus claims that the Persian defeat of the invasion of 480-479 B.C.E was due to their inferior arms and equipment. He also states that Xerxes ‘had many men, but few soldiers’. However, the merit of the leadership of Themistocles, Eurybiades, Leonidas and Pausanias as well as the superior skill of the Greeks cannot be ignored. From the product of their athletic lifestyles also came part of the reason for their victory. Patriotism in fighting for their own land and country, liberty and their morale also attributed to their success. Though the Persians had the ten thousand immortals, cavalry and archers, most of the army was a disorganised amount of different nationalities. Ionian Greeks were forced to fight against their own kin, Egyptians, Phoenicians, Thebans, Thespians, Macedonians, Bactrians, Indians as well as men from Cyrpus, Caria, Lycia and other medizing countries under Persian control were in their army and navy. In arming these men, they had leather helmets, bronze helmets as well as javelins, spears, axes, bows, short swords and hide-covered wicker shields. The Immortals, however, were armed with a covering of metal scales under a loose fitting tunic as well. This was shallow protection as compared to the Greeks. The Greeks wore bronze helmets, breastplates, and greaves, using short swords and spears while holding hoplite shields. Contrasted with the hoplite was the Greek cavalrymen, who were few in number, wore no armour and carried no shield and used spears or javelins. Also in the Greek ranks were the peltastai, light-armoured troops who were mainly used for scouting or raiding in a hit-and-run tactic. The tactic of using the archers on the Persian side proves that they were more used to a ranged attack, whereas Greeks were well-renowned for their abilities in a close-up attack. Greek formations included the phalanx in which each hoplite held his shield over his left side and the right side of his neighbour. The long lances of the rear rank projected beyond the shields of the front rank to confront the enemy. Once the formation was broken, however, the advantage was lost. Another tactic was the wing formation, used in Marathon in a previous invasion. The triremes were also evident and important in the success of the Greeks over the Persians. They had three rows of oarsmen drawn from the thetes class of society, who were usually highly trained professionals. These ships were light and unstable, so the rowers were expected to throw javelins and sling stones from a sitting position. The crew also included 200 archers and hoplites to repel enemy boarders. At the front of the ship was a bronze ram for breaking oars of other ships and possibly bashing in holes into enemy ships. In a naval battle, a formation called the kyklos was used. This was a defensive tactic adopted by outnumbered sleets and formed a circle with the rams pointing outward. The military leaders from Thermopylae, Artemisium, Salamis, Plataea and Mycale were praised for their successes in these battles and the tactics used. During the meeting of the Greek forces in 480, they had decided to defend narrow mountain passes to further their own advantage. Leonidas led his Spartan men and many Athenian men to defend the pass at Thermopylae while Eurybiades and Themistocles were stationed at Artemisium to keep the Persians away in a combined effort. Themistocles’ decree suggests that these battles were merely delaying actions to reduce the numbers of the enemy and give Athens time to evacuate their city. This explains why so few Spartans were present at Thermopylae – only 300 amongst the 7000 Greek troops. Another reason for so little Spartans was that there was a festival on during this time in the city-state, as well as the fact that the Spartans were unlikely to have subjected their main army in Boeotia. Themistocles’ decree suggests a bold and daring plan in which both Athens and Sparta were to carry out their agreed tasks – the Athenians sacrificing their city and Leonidas giving his life. Herodotus tells us of the honour paid to the Spartans who defended Thermopylae: ‘Go tell the Spartans you who read, We took their orders and are dead.’ Prior to this, Themistocles had left messages for the Ionian greeks to change sides and join the Athenians. These are called the Trozen inscriptions and were of great import at the time. Themistocles part in the Persian invasion of 480-479 can not be undermined in that it was he who convinced the Athenians to spend the profit from the silver minds at Laurium on triremes. In this, he was able to hold out at Salamis in one of the most momentous turning points in the war. Having abandoned the battle at Artemisium due to the fall of Leonidas’ troops, Xerxes then marched south. The evacuation of Athens was complete and the ships from Artemisium lay off the island of Salamis. Many of the Greek alliance were in favour of defending only the Peloponnese, but as Plutarch states, Themistocles did not agree as the sea around the Peloponnese was wide and it would give the Greek’s a major disadvantage due to their smaller numbers. The narrow bay of Salamis offered the natural protection that the Greek navy needed. Plutarch claims that Themistocles deliberately chose the time of day ‘when the wind usually blows fresh from the sea’. Plutarch further states that the breeze did not disturb the Greek fleet, as those ships were small and lay low in the water, but the breeze caught the Persian vessels, which were ‘difficult to manoeuvre with their high decks and towering sterns, and swung them around broadside.’ After the battle of Salamis, Xerxes returned home to the Asian continent and left Mardonius in charge of the destruction of Greece. Following this was the battle at Plataea where Pausanias, Leonida’s nephew, led the army. Herodotus tells us that the Spartans ‘dispatched a force of 5000 Spartan troops, each man attended by seven helots’. The battle at Plataea involved a lot of retreating to more advantageous areas and waiting for the other side to attack, which nerved the Spartans, but eventually Pausanias positioned himself near the foothills closer to Plataea. This also gave them better access to a water supply and some protection from Persian attacks. IN surprise, Mardonius engaged his troops, whose sight of the Greeks were obscured by the hills and they believed that they had them on the run. At this point the Greek allies of the Persians, the Thebans and Boetians, cut off the Athenians of the left and there they fought a pitched battle. When the Boetians realised their defeat was imminent, they retreated. At Mycale, a Greek fleet of 250 ships were led by the Spartan king Leotychides. This was the first offensive battle led by the Greeks against the Persians. Other reasons for this battle included an attempt to liberate the Ionian Greeks, to incite revolt amongst them, to prevent the Persian troops from joining Mardonius at Plataea and to ensure that no further Persian invasions occurred. Greek spies from Samos, the headquarters of the Persian fleet reported that the Persian ships were in poor condition. Upon reaching Samos, the Greeks discovered that the Persians had sailed to Mycale and pursued them. Herodotus asserts that ‘this day saw the second Ionian revolt from Persian domination.’ however, Mycale occurred about the same time as Plataea so historians discount this claim. Patriotism, liberty, morale and their athletic lifestyle also contributed to the Greek success. The Ionian revolt led to the Athenians learning of Persian tactics as well as realising the threat to their own land by Persian allied Greek tyrants. Athens had only recently engaged in the rule of democracy, though still developing from plutocracy they had disbanded the tyranny that had held them. This incited them to help in the Ionian revolt as well as defend their country with a strong patriotism. As the Persian’s invaded, it became more evident that the knowledge of the land assisted in the Greek success. Salamis. Examples of this are Thermopylae and In fighting in their own land did the Greeks use this advantage to its fullest. The stamina in which the Greeks under took these battles leant itself very much to their lifestyle. The Olympic Games is a clear indication of this widespread belief in the athletic. At the games at Olympia was included a hoplite event in which a runner would run with heavy armour on or carrying a hoplite shield on their arm. The Spartans also had a lifelong military regime in which their skills became superior and renowned. The performance of the hoplites and the Athenian Pheidippides is honoured in today’s society with the ‘marathon races’. The hoplites ran, carrying about 32kg of armour into battle. After hard fighting, they hurried back to Athens more than 33km away to prepare another resistance to Persian landing. Phiedippides ran from Athens to Sparta, covering 245km in two days in an vain attempt to summon help. The morale gained by the battle of Marathon was one of the most uplifting events for the Greeks as the small amount of Plataeans and Athenians were able to drive back Persian attack in 490 under the leadership of Miltiades. The battles in which the Greeks undertook in 480-479 were successful in driving back the Persians due to their superior skills, armour, patriotism, unity as well as their belief in liberty and their own morale gained at Marathon and Salamis.