Searching in Vain for the Golden City: Anti

advertisement

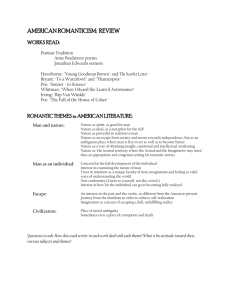

Krautwurst 1 Karen Krautwurst English 200 Dr. Rob Hale April 29, 2003 Searching in Vain for the Golden City: Anti-Religious Symbolism and Metaphor in "Eldorado" "The idea that God is dead is not new to the student of American literature" (Broussard v). Theological discussion of American literature has found a growing interest in the literary critical canon, though some American works lend themselves more toward this approach than others. Traditionally, the poetry and prose of Edgar Allan Poe has not been studied in this vein, "perhaps because of a popular conviction that he was the last literary man in the world we should expect to find among the prophets" (Forrest 5). Because of his professed atheistic beliefs, Poe's work has only been reluctantly viewed in a religious context. However, it is possible to analyze certain texts in light of his views to discover greater depths of meaning; such is the case in his poem, "Eldorado." Despite the popular estimation that "Eldorado" is an allegorical work about the Gold Rush, greater meaning can be found if it is read with regard to religious representation as a comment on the author's theological convictions. Poe's use of biblical symbolism and religious metaphor in "Eldorado" illustrate his own view of religion as a futile quest. In order to understand Poe's stand on religion as it is revealed in "Eldorado," one must become familiar with his views through a study of his biography. As revealed in N. Bryllion Fagin's biography of the poet, Edgar Allan Poe was born on January 19, 1809 in Boston, Massachusetts. His parents were both actors, but ultimately provided very little inspiration to Poe; his father disappeared when he was still young, and his mother passed away shortly after. Krautwurst 2 As a result, young Edgar was unofficially adopted by Mr. John Allan and affixed his surname to what would eventually become Poe's famous designation (4-5). Relations between John Allan and Poe became strained after Poe's one-year jaunt at the University of Virginia, where the structure of University life proved not to his liking, and he racked up an excess of gambling debts. He joined the army in 1827 under the name Edgar A. Perry, and served for a period at the rank of Sergeant Major before being honorably discharged to attend West Point Academy. Again, the rigidity of the regimented academy stifled Poe, and he was court-martialed and dismissed after less than a year of attendance (Fagin 5-6). This pattern of deviation from regimented routine may have laid the initial groundwork for Poe's tendency to shy from the structure of religion. The general consensus on Poe's religious convictions is that they were non-existent. He professed in personal correspondence to be an atheist although, according to Augustus Hopkins Strong, his atheism was "an atheism of the heart, rather than an atheism of the head. He lacked the will to believe. The secret of professed atheism is really a dislike for the character and the requirements of God" (182). Poe's independent nature rebelled against the mandates of organized religion, specifically the Christian doctrines which provide the framework for the faith. Arrogance and an inflated sense of self-esteem likely also contributed to Poe's resistance to religion. The basis of religious belief is a blind acceptance of that which cannot be proven and which is ultimately greater than any known entity. Poe was unwilling to accept something so great. In his own words, "'My whole nature utterly revolts […] at the idea that there is any Being in the universe superior to myself!" (Strong 183). Such a statement may seem to be quite an overestimation of egoism, but Poe's confidence in his own magnanimity was no greater than the Krautwurst 3 common Christian's regard for his God. As such, it is reasonable to suggest, as Strong does, that Poe's extreme confidence in himself replaces any confidence in a god because "theism humbles man's pride, implies his dependence, as a creature and as a sinner" (182). Poe's own self-labeling as an atheist is slightly incorrect by most accounts. He often invoked the name of God in his writing. He also seemed to hold a belief in the existence of a soul, even that the soul lives on beyond the expiration of the body, but the organization of religion, as well as the submissiveness to a supreme being required to maintain such a faith, remained elusive to Poe. His faith, as it were, was reliant on the workings of his own mind and spirit. Though he rebelled against structure and doctrine, without them his religious concepts "are dangerously near being repulsive, and often they are an expression, not so much of hope, as of despair" (Bailey 45). Poe viewed religion as a futile quest for man to justify his own existence. Poe's poem "Eldorado" can be read in view of this conviction as a statement condemning the search for God as futile. The legendary city of Eldorado itself, to which the poem directly refers, is a metaphor for God or the path to Him and His salvation. It is sought at great length, but remains elusive as time passes without results. There are two characters in "Eldorado"—a "gallant knight" (2) and a "pilgrim shadow" (15). These two images are significant in reading the poem as a commentary against religion. Traditionally, the knight is a questing figure of subservience. He serves his king, loyal to the point of blind battling. The image of servitude casts the knight as a metaphor for the loyal Christian, a servant of God. The knight's subservience is to an unnamed liege lord; the loyal Christian servant's it to Christ the King. Krautwurst 4 Poe uses the knight, in addition to representing the metaphorical good Christian, to interject a small part of himself into the poem. Though Poe, by most accounts, did not actively seek God or spiritual guidance, shades of his life are shown in the character of the knight. Most tellingly is the knight’s solitude. Fagin reports that, orphaned at a young age and adopted by an upper class gentleman, Poe was often very isolated. Taken from a background as the son of actors and placed in an aristocratic setting, Poe often felt that “he was among ladies and gentlemen on sufferance only, that he did not belong among them and never could” (34). Poe’s seclusion from his immediate circle is reflected in his knight’s apparently long and solitary journey. The pilgrim shadow in "Eldorado" is a figure of uncertainty. The connotations of "shadow" and "shade" which are both used to describe the character invoke images of wavering certainty and illusion. The pilgrim shadow's purpose in the poem is to provide guidance for the lost knight—to show him the way to Eldorado. Poe chooses a questionable and intangible guide for his knight, insinuating that those who would guide man toward God are insubstantial if not outright false. In the first stanza of the poem, Poe describes his knight journeying, "In sunshine and in shadow" (3). This line sets up the contrast between light and dark, or perhaps more precisely, knowledge and uncertainty. The knight perseveres through both sunshine and shadow; the loyal Christian maintains his faith through both times of surety and doubt. The entire first stanza characterizes the knight, and the metaphorical Christian, as steadfast and committed. Poe incorporates the image of the knight "singing a song" (5) as he continues on his quest, which could be compared to the Christian worship songs and hymns. Krautwurst 5 In the second stanza of "Eldorado," Poe begins to make his point about the futility of a religious quest. His knight, who began the poem "gailey bedight" (1) and "singing a song" (5) is now growing old and weary. He has traveled without any sign of Eldorado: And o'er his heart a shadow Fell as he found No spot of ground That looked like Eldorado. (9-12) The quest is turning up no evidence of that which the knight seeks. The metaphor of the shadow in this stanza is one of doubt and despair. It is, "clearly a figurative word, referring to the dark weights that oppress the soul…" (Sanderlin 189). As no proof of his "Eldorado" is found, dark disbelief begins to creep into the heart of the questor. Poe's message is that religion is founded on a basis of trust without proof, and eventually every man will need that unavailable proof to ground his faith. Without it, he cannot keep doubt at bay. In the third stanza, Poe's knight encounters the pilgrim shadow as his strength wavers. The shadow is a metaphor for some form of spiritual leader. His strength fading, the knight pleads for answers, "'Shadow,' said he/ 'Where can it be-/ This land of Eldorado?'" (16-18). The knight cannot travel further on his own, so he seeks guidance from the phantom shepherd; the dedicated Christian cannot persevere relying only on the faith in his weak heart, so he must plead for guidance from some other source. In this case, Poe makes the source of enlightenment one that is questionable, for its very form is immaterial. The knight/Christian seeks solid proof from an insubstantial source; the probability of gaining any information that is trustworthy or useful is gravely doubted. The fourth and final stanza of "Eldorado" gives the shadow's answer to the knight's plea: Krautwurst 6 'Over the Mountains Of the Moon Down the Valley of the Shadow Ride, boldly ride' The shade replied'If you seek for Eldorado!' (19-24). Line 19 makes reference to the Mountains of the Moon, also known as the, "Montes Lunae of antiquity, at the foot of which the Nile is supposed to rise" (Leeds 44). The mountains were widely alluded to by geographers, but they were believed to be no more than a legend because no travelers had ever actually come across them (Leeds 44). Poe's use of this particular image is significant in characterizing the knight's quest for something false. According to Leeds, "it seems likely that the poem's allusion to the Mountains of the Moon, in keeping with that to Eldorado, functions ironically to call up an image of the impossible quest…." (44). Poe's next allusion, "Down the Valley of the Shadow" (21) is an obvious biblical reference to Psalms 23:4, "Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death." In the Bible, the valley of the shadow of death is a reference to dark fear, set up in contrast to the safe, guiding light of God. The verse goes on, "Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil; for thou art with me" (Holy Bible, Psalms 23.4). The dark foreboding of the "valley of the shadow" is immediately soothed with the promise of salvation from God's presence. In Poe's "Eldorado" however, there is no counteracting light. The knight is instructed only to ride into the Valley of the Shadow, not promised comfort. The knight's guide tells him to "Ride, boldly ride" (22) through these two allusions. The word "boldly" seems especially significant given the nature of both references. The knight is Krautwurst 7 being instructed to travel unhesitantly through places of uncertainty and fear in order to reach his destination. Poe's metaphors all work together to make a very ominous claim—that to seek religious conviction, the dedicated Christian must keep on without thinking, without questioning, through skepticism and dread. One must not expect a definite destination—it may not exist. One must not expect a balm for fear—it will not be there. If the religious stop to question their beliefs, they may lose all conviction. The final line of the poem, "If you seek for Eldorado" (24) contains the all-important final choice. The conditional word "if" must not be discounted. The knight, and his metaphorical counterpart, the Christian, faces a choice of dedication. The path he must follow has been laid out for him, but he need not pursue it. The shade implies that the severity of the knight's quest is such that he must consider carefully the strength of his conviction. As stated by Sanderlin, "the shade may well be declaring, 'Ride, boldly ride, if you seek for Eldorado. Your gallantry is laudable, but in the end you will merely continue your search beyond the grave, becoming another pilgrim shade like me'" (191). In essence, the pilgrim shadow's point is a reflection of Poe's—the quest is futile, however noble the journey may be. Throughout "Eldorado" Poe uses metaphor and symbolism to make a negative statement about the quest for religious satisfaction. At face value, his writing would support his own theory that he was an atheist. Digging deeper, however, one gains the impression that Poe's aversion to religion was one of frustrated attempts rather than blatant dismissal. The quest of the knight, after all, starts out optimistic. Is Poe the knight, desirous of Eldorado but destined to fail? If so, then his religious convictions, rather than being non-existent, would be better interpreted as stunted by the shadows of his lifetime. Rather than travel the despairing and uncertain path, Poe chose to return without a glimpse of Eldorado. Krautwurst 8 Works Cited Bailey, Elmer James. Religious Thought in the Greater American Poets. New York: Books for Libraries Press, 1968. Broussard, Louis. The Measure of Poe. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1969. Fagin, N. Bryllion. The Histrionic Mr. Poe. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1949. Forrest, William Mentzel. Biblical Allusions in Poe. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1928. Holy Bible: King James Version. American Bible Society: New York, 1992. Leeds, Fredric M. "The Mountains of the Moon in 'Eldorado'." Poe Studies 10 (1977): 44. Sanderlin, W. Stephen. "Poe's Eldorado Again." Modern Language Notes 71 (1956): 189-92. Strong, Augustus Hopkins. American Poets and Their Theology. Philadelphia: The Griffith and Rowland Press, 1916.