Workers and Their Organisations

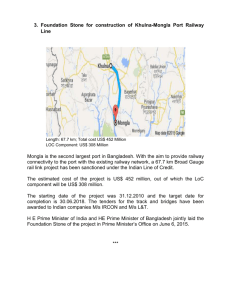

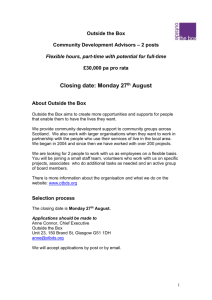

advertisement