chapter 5

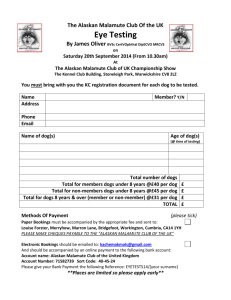

advertisement