aar 4812 / boligens teori og historie

advertisement

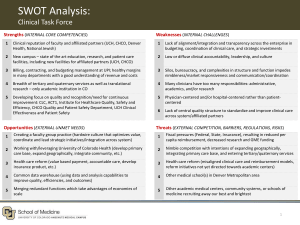

AAR 4812 / Theory and history of housing 06. September 2013 Critical voices I - Structuralism and low-dense movement As we have seen, during the first decades after the second WW, aspects of modernism such as industrialisation, mass production and standardisation had a great impact on cities all around the world. This happened clearly as a response to housing shortage and bad living conditions for the growing urban population – set back by the war. And technically it led to an improved housing standard for thousand if not millions of people. Still – more and more critical voices was heard both within and outside the architectural profession. In fact, most of the ideas and theories that have marked the architectural debate after the war in one way or another were critical to aspects and results of the modern movement and it approach to housing and urban planning. In the rest of this lecture and the next, I will present some of these critiques. Ideological confrontation with modernism CIAM (Congres Internationaux d’Architecture) – the organisation gathering the modernists who dominated the debate, and with the swiss historian and theorist Sigfried Gideon as a secretary – was established in 1928. They had several meetings before the second WW, among others the one in Frankfurt, arranged by Ernst May in 1929 with ‘Dwelling for the existence minimum’ was the topic. And on a boat in the Mediterranean in 1933 where they agreed on the so called Athen-charter which advocated the zoning of the city 1 according to four different functions: living, working, recreation and transportation. (Lund, 2001:60). After the world war, several young architects believed the CIAM became too dogmatic and questioned among others things their approach to the city. They still worked within the organisation and in 1959 a group, who named themselves Team 10, organised a conference in Otterloo (Netherlands) which gained a great impact on the future debate. Not at least because the discussions were publicised in a book later on (Team 10 Primer). Among the participants were Aldo van Eyck, Alison & Peter Smithson, Kenzo Tange, Oskar Hansen, Louis Kahn, Arne Korsmo and Ralph Erskine. A diverse group with rather different approaches and viewpoints. Common for them was however that they were critical to the direction that modern architecture and urban planning had taken. It was regarded as too static and custom-made (tailor-made) for only one purpose at the time (Guttu:223). Slide xx: critique Situationism Slide: alternative utopies This term is used to designate utopian, revolutionary ideas where changeability played an important role: ”ephemeral, temporary, multiinterpretable architecture” (Bosma, 2000:46) A lightness in urban design – often illustrated as megastructures. Presented as an alternative to the functional poverty that marked the modern movement – open spaces in the city should offer situations for action and activities. They had confidence in the creativity of the masses, quite a different approach to the role of the planner within modernism – as the omniscient expert – who knows best on behalf of the masses. The nomadic life was furthermore regarded as part of modern life – but an issue that was not taken care of in conventional urban planning. ‘The dynamic labyrinth’ was the ultimate urban 2 concept: ”The occupier as the produces of space. The architect has, at most, a supporting role as an intermediary between consumer and producer” (ibid:52) Examples: Constant Nieuwenhuys / Debord: New Babylon "Town planning is not industrial design, the city is not a functional object, aesthetically sound or otherwise; the city is an artificial landscape built by human beings in which the adventure of our life unfolds.” Constant Nieuwenhuys, 1960 A theoretical model, a global, post-revolutionary state which emphasizes the nomadic way of life rather then static, individual settlements. They imagine a society where all production of commodities is fully automatic, where leisure is more important than work and where all land is collectivized: ”The act of creating is more important than the product created, and the act of travelling outweighs arriving at one’s destination. Life has the features of a road movie” (Bosma, 2000:51). Home ludens,( ‘the playing man’) is what characterize humans in the post-industrial period where work no longer is important. Archigram London based group consisting of 6 architects (1960s): Peter Cook, Dennis Crompton, Ron Herron, Michael Webb, Warren Chalk. They established a Magazine with the same name: representing an enthusiastic and disrespectful critique of conventional modern planning (NO Lund, 2001:158). Marked by popular culture and fascinated by technological structures, according to Nils Ole Lund ”beruset av forbrugersamfundets tilbud om den totale utfoldelse” (ibid): “elated by the consumer societies offer on total display” Combination of science-fiction and cartoons. No normal cities but a, but a conglomerate of towers, cranes, pipes, refinery and oil drilling platforms translated into a city. 3 Slide - Walking city: Architecture is not regarded as fixed physical frames (shelter) but rather as structures linking individuals to the society. Slide - Plug-in city: A fast changing and mechanized world – best expressed thorugh the idea of the ”Plug-in” city (Peter Cook) Slide - Instant city: The city as a mobile technological system floating in the air in balloons with temporary structures (performance spaces) over underdeveloped, sad and grey urban areas. The situationists did not build many projects – they were rather artistic visions publicized in magazines and exhibitions. But became all the same important in the professional debate in the 60s. With their freshness and radical approach they managed to call attention to some of the weaknesses of the modern movement – the idea that buildings and cities are static entities with a range of use given once and for all. These ideas were followed up by several other architects – who were more down to earth and aimed to influence the production of new housing in ‘real life’. Learning from the vernacular Bernard Rudofsky: Architecture without architects (ref. F. Scott’s article) On one hand – modernists inspired by images of Mediterranean hill towns. Rudofsky, himself a modernist – an architect working with the modernist vocabulary - became an outspoken critic of the modern movement. The exhibition at MOMA 1965 – was an attack on the state of modern architecture. Vernacular architecture offered an alternative to the condition of architecture: cultural homogenization and monotony rising from an increasing degree of commercialisation of the built environment. He was (according to Scott) much occupied 4 with the sensuality and richness of vernacular architecture. But also with how it’s temporality and sometimes even movability was relevant to the nomadic existence of modern man (just like the situationalists): “the nomad represented an alternative strategy of occupying territory” (Scott, p218) Structrualism: Open form / open building / flexibility Oskar Hansen (Emphasised the interplay between society and indivduals in mass production) The Polish architect Oskar Hansen gave a presentation at the CIAM Otterloo 1959 conference on open form: ”The open form in architecture – the art of great number” (Den åpne form i arkitekturen – det store antalls kunst”). Starting point – the problem of great numbers. 1. ”In spaces which are defined by a great number of similar forms and monotonous lines – which are impossible to experience – we will feel lonely and abandoned” 2. ”Time is today an more important factor than ever before, and we can no longer make use of fixed elements. Our creations are obsolete (out dated) the moment they are created. (…) They do not open up for the essential: Respect for the individual and for the spontaneity of each one of them” ”Open form is characterised by an enlargement of subjective element on the expense of the objective. The new system utilize the industrial production system giving the specialists responsibility for the objective elements (the closed, fixed form) while the subjective elements are left to the users’ initiative. (…) Open form means adapting space to human needs and movements” (Lund) 5 From the lecture by Oscar Hansen ”På sporet af den åbne forms elementer” (‘On the track of the elements of open form’) (quoted and translated from Lund, 2001:62-63) Hansen had mainly three objections against functionalism (according to N O Lund): 1. That individual need are not sufficiently considered - Some decisions should be left to the individual, the product should be possible to adapt to specific needs 2. That changing needs and user patterns are not sufficiently considered - It should be possible to supplement or substitute existing functions with new ones within the same structure (the functional margin) 3. That architecture was adapted to a specific way of life (formal critique) - It should be possible to add new forms without disturbing the totality Open form – still a living idea – and basis for the establishment of Bergen School of Architecture, by Svein Hatløy Ny? Lucien Kroll: La Mémé (1970-72) Student accommodation Lueven outside Brussels NJ Habraken: Supports (1961/1972): ‘Open building’ The Dutch architect and researcher NJ Habraken published early in the 1960s the book ”Supports: an alternative to mass housing”. With this he became a pioneer for a movement named ’open building’. It has quite a lot in common with Oskar Hansen’s ‘open form’ but focused more on the production system and not so much on user influence and formal variation and spontaneity: 6 • A building consists of several layers. Necessary to separate between ”support” and ”infill”: Some should be fixed and some changeable • User and residents should have influence on their home environment • Acknowledging that production of houses involve several actors and professions. Architects work in teams • The meeting between different technical systems should be designed in a way which makes it possible to replace one system with another with a similar function • Acknowledging that the built environment is continuously changing – and the need to comprehend these changes • The built environment is a result of a continuous design process in which the surroundings change step by step. Habraken was (still is) a spokesman for a critical approach to modernism which has been named ”structuralism”, where it was important to include the human scale, open of for changes, regard buildings more as living organisms etc. Flexibility and adaptability became important issues. Furthermore, Habraken was an advocate for involving users and residents in the design process. He proposed to do this by introducing a systematic division between elements decided by the designers and mass produced commodities / products among which the users could choose (Guttu, 2003:224) Ideales: Changeability, variation and incompleteness – as a contrast to the mass produced satellite towns which were perceived as too static, authoritarian and alienating (fremmedgjørende) – without any user influence. Even within a system of mass production of housing, Habraken believed that it could be possible to achieve an interplay between 7 house and resident: ”..the anonymous client can also use architecture to develop a personal form of housing” (Bosma, 2000:65). A grid system was used as a basis (both on building and area level) – buildings were seen as a stage in a continuous development process – where all parts in principle may grow. Construction system: Seperation between permanent constructions and changeable elements (furnishing, equipment, non bearing inner walls etc) – open for individual variation within fixed frames, a certain (limited) kind of user participation. Structuralism also led to several examples of module-construction. Slide: Habitat 67 By combining the modules in different ways, adding and subtracting it opened up for individual variations. It aimed create a greater accordance between the physical and the social structures. Furthermore one tried to recreate a kind of a village quality with repetetive elements and various combinations and groupings of the modules in different kinds of rows and clusters. Habitat 67 is a well known example. Built for the world exhibition in 1967. Made up by concrete modules in a manner that should create vertical spatial diversity – with a density similar to a high rise building – but with much more variation and individuality. Gives associations to a kind of mountain village. Should provide privacy, fresh air, sun and other suburban qualities in an urban situation. Planned to be 1000 units – but ended up with only 158. became too expensive and technically complicated. Slide: pueblos 8 Slides: Skjettenbyen Norway: Hultberg & Seablom (1966-7) (adapted from Guttu, 2003:225): Residents regarded as an individualised diversity – not only as member of a standard nuclear family A new role of planners introduced, their task was more organisation and adaption rather than designing all details Idea of users’ co-determination Low-dense structures as alternative to both detached houses and high rise buildings Preconditions (according to Guttu, 2003:226) Mass production o Unknown users, the dwelling had to be adapted after completion Without assumptions o Within the modernist tradition, the architects start with ‘clean sheets’, they redefine the basic housing needs – aiming to break with locked-in conceptions” (ibid) Trust in technology o Provided possibilities for equality and creativity among residents The strict physical structure – a condition for individual display o Individual display should not get out of control – happen within the restrictions of the totality Slide 32: Critique of the flexibility idea Slide 33: Herman Herzberger 9 Slide 35 Community and Privacy Alexander & Chermayeff (1963) In Community and Privacy Christopher Alexander and Serge Chermayeff (1963) were spokesmen for the establishment of a clear hierarchi of levels between the really public and the very private – they criticized modernism for not taking seriously peoples’ need to protect their privacy in an urban context: ”We are interested, principally, in establishing the integrity of those places where the smaller human scales of immediate experience are possible” (p.121) Urban – Public: arealer som det offentlige / samfunnet eier i fellesskap: Byrom, parker, veier osv Urban – Semi – Public: Offentlig arealer men under kontroll og med begrenset tilgjengelighet og åpningstid. F.eks bibliotek, skoler, sykehus ++ Group – Public: Der hvor en boliggruppe møter offentligheten. Postkasser, søppelhenting, diverse service, tilgang for brannbiler og lignende Group – Private: Sekundære arealer felles for flere husholdninger. Inngang, trappeoppgang, felles gårdsrom / uteplass osv Family – Private: Kontrollert av den enkelte husholdning: Familieaktiviteter – måltider, underholdning, hygiene, vedlikehold Individual – Private: En eget rom – stedet for individuell tilbaketrekning Slide: historical and vernacular examples of the same hierarchi Show historical and vernacular examples where the transitions from the public to the private is clearly and considerately articulated. One move sequentially from the publicly accessible areas to continuously more private. 10 This knowledge might have been lost in many contemporary urban housing projects – characterised by high degree of transparency with glass walls which almost dissolve the difference between private and public – indoor and outdoor. Or it might be that the ideas of Alexander and Chermayeff – which came to have great influence on much of the housing in the 70s – no longer have the same validity. Slides: Example, privacy and community Siedlung Halen, Sveits (1962) Atelier 5. 81 units. Dalen Hageby Meek borettslag 1970-tallet: User participation In the 60s open form was expressed through a constructive and functional flexibility (structuralism), while in 70s the focus was more on participation in the design and building process. Slide 60: Cultural shift Slide 61: From high-rise to low-rise Slide 62: Direct user participation – instead of adaptation through ‘planned flexibility’. Real power and influence on own residential situation Involvement and democracy became important issues in the student movement by at the end of the 1960s. In several cities, students and artists occupied urban areas threatened by demolishing and fought for the preservation and for their right to influence their own environment – with simple means. This was a protest against the alienation they regarded as a result of modern city planning. Fight for self- determination, and for the freedom to choose how to live to 11 control ones own life. Protest against capitalists that made profit on ordinary peoples housing needs etc. Examples: Christiania i København. + Berlin. In Trondheim: Bakklandet and later Svartlamon Examples: Developments (architect led?) where future residents took part in the planning and design process Ralph Erskine: Byker Development (1969-81) Wikipedia: Its Functionalist Romantic styling with textured, complex facades, colourful brick, wood and plastic panels, attention to context and relatively low-rise construction represented a major break with the Brutalist high-rise architectural orthodoxy of the time. Municipal Dreams in Housing, Newcastle: The principle of consultation was fulfilled in two main ways – through a pilot scheme involving 46 households working with architects in the design of their future homes and, more significantly, by shop-front offices in the middle of redevelopment to which residents could drop in. (They did – in large numbers – though often to raise concerns that the architects themselves were powerless to deal with.) How real and effective this consultation process actually was is open to question. One critical observer concluded that ‘the real power to decide what should be done, and when, lay outside the community, in the Civic Centre’.(2) Perhaps this was inevitable given the constraints of finance and law and the politics of competing priorities. A clearer-cut and more objective criticism lies in the failure to fulfil the first object of the scheme – the preservation of the Byker community. A population of 12,000 in 1968 was reduced to around 4400 in 1979. Of new homes, only about half went to locals. Years of planning blight, long delays in construction, a slow pace of demolition and the sheer disruption of redevelopment had forced around 5000 households out of the area. 12 The build quality was poor and major refurbishment has been necessary. This has been costly (the more so now given the estate’s listed status) and ongoing. Most significantly, the community has changed. This is not principally the result of some malign social engineering in the scheme itself. Much more it results from social and economic shifts that have damaged working-class communities – and social housing in particular – across the country. As traditional local industries – notably the shipbuilding staple of Tyneside – declined in the 1980s, unemployment on the estate reached 30 per cent. It remained three times the national average (at almost 12 per cent) in the early 2000s. Unsurprisingly, levels of deprivation and complaints of antisocial behaviour rose accordingly. So it’s a mixed picture. There is certainly much to celebrate in Byker – the vision which inspired it, the daring and decency of its overall design, even a continuing record of community involvement, flawed though it has been The failings and shortfalls are undeniable too. Some of these may have been avoidable but reflect an eternal reality of investment never quite matching aspiration. Others seem to have resulted from intractable social dynamics – though, in this case, we shouldn’t forget the political choices which helped forge these apparent inevitabilities. Selegrend 1, Bergen (1974) (Tinggården 1, Vandkunsten (1978)) The naked city (Asger Jorn / Guy Debord) Sosialistisk / systemkritisk innfallsvinkel: De som er mest direkte berørt av planleggingen har verken makt eller midler (tools) til å påvirke omgivelsene etter sine behov og ønsker. Et byområde er 13 geografisk-økonomisk enhet, men gir også et bilde av de som bor der: ”psycho-geography”. ”The naked city”: 19 fragmenter av Paris sin byplan (Jardin de luxemborg, Gare de lyon, les halles etc) klippet ut og forbundet med røde piler. Resultatet av denne fragmenteringen er det de kaller for et ”psycho-geographical” kart over byen som en form for sosial kropp(sosialt fenomen?) med subjektive følelsesmessige verdier og unike atmosfærer. Både en kritikk av tradisjonell kartlegging av byens funksjoner og en undersøkelse av sammenhengen mellom ulike urbane elementer – ved å sette dem sammen på en ny måte. C. Alexander (1977): ”Pattern language” Alexander har en veldig rasjonell tilnærming til arkitektur og bygde omgivelser, og inngår sånn sett tydelig i modernismens fagtradisjon. Men han regnes også som en representant for strukturalismen. Han foreslår et system av mønstre, en orden, som strukturerer fysiske omgivelser på samme måte som vi finner det i naturen, i levende strukturer. Og han er opptatt av prosesser: Han sammenligner og finner inspirasjon i biologiske prosesser når han beskriver kulturelle og sosiale prosesser som former menneskelige omgivelser og bygninger. Målet er å utvikle omgivelser der mennesker og menneskelig målestokk er utgangspunktet, og som gir rom for menneskelige behov og vekstmuligheter. Pattern language – mønsterspråk - er basert på en hypotese om at mennesker har en universell evne til å kommunisere gjennom omgivelser som er parallell til deres kommunisere gjennom talespråk. Et sett av mønstre blir til et mønsterspråk når et mønster leder videre til nye mønster. Han er blant annet kritisk til den måten boliger og omgivelser produseres på (industrielt), som han mener motarbeider den levende 14 prosessen som er en forutsetning for å skape menneskelige omgivelser. Også kritiske til den funksjonsdelte Byen i en tekst som heter ”the city is not a tree” – argumenterer for at den levende byen må ha en struktur som muliggjør overlappende nettverk av funksjoner. I ”pattern language” foreslår han en rekke mønstre for fysiske omgivelser – helt fra bynivå og ned til det enkelte rom. Det er ikke ment som et statisk system, hver kultur, hver kontekst skaper sine mønstre og mønstrene må utvikles av menneskene som skal bruke dem. 15