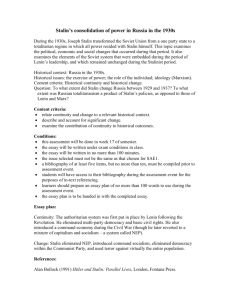

Long-term problems faced by Russia before the outbreak of World

advertisement