Week 12 Lecture Notes Inventory

advertisement

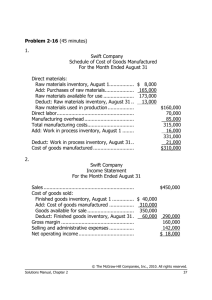

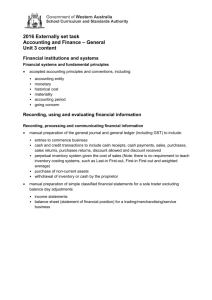

Week 5 Lecture Notes Accounting for Inventory Introduction to Inventory Inventory (or stock) is the term used for goods bought or manufactured for resale but which are as yet unsold. Inventory enables the timing difference between production capacity and customer demand to be smoothed. The value of inventory according to AASB102 Inventories is the lower of cost and net realisable value. The cost of inventory includes all costs of purchase, conversion (i.e. manufacture) and other costs incurred in bringing the inventory to its present location and condition. Costs of purchase therefore include import duties and transportation, less any rebates or discounts. Costs of conversion include direct labour and an allocation of both fixed and variable production overheads (overheads are covered in chapter 13, weeks 7 & 8). Special methods of calculating inventory value apply to construction contracts, agriculture and commodities trading. As students would have learned in financial accounting (see Chapter 6 of the text) the matching principle requires that business adjusts for changes in inventory in its Income Statement (the ‘cost of goods sold’) and in its Balance Sheet (inventory is a current asset). The cost of goods sold is calculated as shown in the following example: $ Opening inventory (at beginning of period) 12,000 Plus purchases (or cost of manufacture) 32,000 = Stock available for sale 44,000 Less closing inventory (at end of period) 10,000 = Cost of goods sold 34,000 For a retailer, inventory is the cost of goods bought for resale. For a manufacturer, there are three different types of inventory Raw materials Work in progress Finished goods Manufacturing firms purchase raw materials (unprocessed goods) and undertake the conversion process through the application of labour, machinery and know-how to manufacture finished goods. The finished goods are then available to be sold to customers. Work-in-progress consists of goods that have begun but have not yet completed the conversion process. Flow of costs Figures 1 and 2 show in diagram form the flow of costs from purchasing to sales for a retail organisation (Figure 1) and for a manufacturer (Figure 2). Page 1 Figure 1: The flow of costs in purchasing Inventory Finished Goods Increases inventory Cost of sales Purchases Sales Decreases inventory Increases cost of sales Figure 2: The flow of costs in manufacturing Inventory Raw materials Purchases Increases inventory Issued to production Decreases inventory Inventory Work in progress Cost of sales Increases inventory Production labour Increases inventory Production overhead Increases inventory Completed production Decreases inventory Sales of finished goods Inventory Finished goods Increases inventory Decreases inventory Page 2 Increases cost of sales Figure 3: The flow of costs in backflush costing Inventory Raw materials Purchases Increases inventory Completed production Decreases inventory Inventory Finished goods Cost of sales Increases inventory Conversion costs Increases inventory Sales of finished goods Decreases inventory Increases cost of sales Page 3 Cost formulas for inventory Inventory valuation is important as the determination of the cost of inventory affects both: Cost of sales in the Income Statement, and The inventory valuation in the Balance Sheet. The valuation of inventory is therefore an important link between financial accounting and management accounting. The cost of inventory items that are not interchangeable or are segregated for specific projects are assigned by the specific identification of their individual costs. So for example, a component purchased for a specific job with a cost of $600 but unused, would be valued at $600. However, if inventory items are similar and cannot be differentiated, costs are assigned by using either the weighted average cost or first-in, first-out (FIFO) methods. The last-in, first-out (LIFO) method, common in the United States, is not acceptable in Australia or the UK. Inventory valuation under Weighted Average method Under the weighted average method, the cost of each item is determined from the weighted average of the cost of similar items at the beginning of a period and the cost of similar items purchased or produced during the period. A product is purchased on three separate occasions: Units Unit price Total cost 5,000 $1.20 $6,000 2,000 $1.25 $2,500 3,000 $1.27 $3,810 10,000 $12,310 Calculate the cost of 6,000 units sold and the value of inventory using the weighted average method. The weighted average cost is $12,310/10,000 or $1.231 per unit. The cost of goods sold is 6,000 @ $1.231 = $7,386 The value of inventory is 4,000 @ $1.231 = $4,924 Page 4 Inventory valuation under FIFO FIFO assumes that items of inventory purchased or produced first are sold first, so that those remaining in inventory are those most recently purchased or produced. Using the same information: Units Unit price 5,000 $1.20 2,000 $1.25 3,000 $1.27 10,000 Total cost $6,000 $2,500 $3,810 $12,310 Calculate the cost of 6,000 units sold and the value of inventory using the FIFO method. Under FIFO, the 6,000 units sold come first from the original 5,000 purchased, and the balance of 1,000 from the second purchase of 2,000 units. The cost of goods sold is therefore: 5,000 @ $1.20 = $6,000 and 1,000 @ $1.25 = 1,250 Total = $7,250 The remaining inventory is the last purchased, i.e. 1,000 from the second purchase of 2,000 and 3,000 from the third purchase. The value of inventory is therefore: 1,000 @ $1.25 = $1,250 and 3,000 @ $1.27 = 3,810 Total $5,060 Note that depending on the method used, the cost of sales (and therefore profit) differs. If the 6,000 units were sold at a price of $2.00 Under weighted average the gross profit would be $4,614 ($12,000 - $7,386). Under FIFO the gross profit would be $4,750 ($12,000 – $7,250). Retail method The retail method is used for the measurement of inventory cost for retail organisations where there are large numbers of rapidly changing items with similar margins. The retail method of inventory valuation determines the cost of inventory by deducting an appropriate percentage profit margin from the sales value of inventory. Net realisable value Where the net realisable value is less than cost, this value should be used for inventory valuation. The net realisable value is the proceeds of sale, less any costs of disposal (e.g. transport, cleaning, etc.) The realisable value could be a discounted sales value, trade-in value, scrap value, etc. which is lower than the cost of purchase (or cost of production). Page 5 Methods of costing inventory in manufacturing There are different types of manufacturing and it is important to differentiate alternative methods of production to which different methods apply for the calculation of cost of sales and the value of inventory: Custom: Unique, custom products produced singly, e.g. a building. Batch: A quantity of the same goods produced at the same time (often called a production run), e.g. textbooks. Continuous: Products produced in a continuous production process, e.g. oil and chemicals, soft drinks, etc. For custom and batch manufacture, costs are collected through a job costing system that accumulates the cost of raw materials as they are issued to each job (either a custom product or a batch of products) and the cost of time spent by different categories of labour. To each of these costs overhead is allocated to cover the fixed and variable manufacturing overheads that are not included in materials or labour (overhead will be explained in Chapter 13). When a custom product is completed, the accumulated cost of materials, labour and overhead is the cost of that custom product. For each batch the total job cost is divided by the number of units produced (e.g. the number of copies of the textbook) to give a cost per unit (i.e. cost per textbook). For continuous manufacture a process costing system is used, under which costs are collected over a period of time, together with a measure of the volume of production. At the end of the accounting period, the total costs are divided by the volume produced to give a cost per unit of volume. Under a process costing system, materials are issued to production, but as labour hours cannot be allocated to continuously produced products, conversion costs comprise the production labour and production overhead. In process costing, equivalent units measure the resources used in production relative to the resources necessary to complete all units. Examples of job and process costing are in the next section. In both cases, two important documents record the costs being incurred: Material issues: record the quantity of material issued from raw materials to production. Timesheets: record the number of hours worked by production labour to convert the raw material to finished goods. Backflush costing The introduction by many manufacturing companies of Just-in-Time (JIT) is intended to bring components from suppliers to the assembly line as they are required for production, rather than for the manufacturer to hold large quantities of raw materials to meet future production requirements. JIT has resulted in a significant reduction in inventories and so inventory valuation becomes less relevant. Under traditional costing approaches, each material issues transaction is recorded separately. Backflush costing aims to eliminate detailed transaction processing. Rather than tracking each movement of materials, the output from the production process determines (based on bills of materials and standard costs) the amount of Page 6 materials to be transferred from raw materials to finished goods. Importantly, under backflush costing there is no separate accounting for work in progress. The timing of the recording of costs is based on a trigger point. In its simplest version, backflush costing transfers the cost of materials from suppliers, and conversion costs, to finished goods inventory when production of finished goods is complete (the trigger point). In a modified version, trigger points occur when raw materials are purchased and when finished goods are completed. The modified version is shown in Figure 3. Job costing illustration Helo Pty Ltd manufactures components for helicopters. It does so in batches of 100 components. Each batch requires 500 kgs of rolled and formed steel, which takes 15 hours of labour. During the course of a month, the following transactions take place: Purchase of steel 1,000kgs @ $12/kg Issue of steel to production 500 kgs Direct labour to roll and form 500 kgs steel 15 hours @ $125/hour Overhead allocated at completion of production of 100 components $2,000. 60 of the components manufactured in the batch were sold for $130 each. At month end, 500 kgs of steel has been issued to production and 7 hours have been worked. The job is incomplete. Calculate the value of work in progress at month end. Work in progress will comprise Materials: Steel 500 kgs @ $12/kg Labour: 7 hours @ $125 Work in progress $6,000 875 $6,875 After completion of the job, calculate: The unit cost of production The gross profit The value of inventory. Page 7 The job cost for the production of a batch of 100 components is as follows: Materials: Steel 500 kgs @ $12/kg $6,000 Labour: 15 hours @ $125 1,875 Overhead 2,000 Total job cost $9,875 Cost per component $98.75 ($9,875/100) The cost of sales of the 60 components sold is $5,925 (60 @ $98.75). The sales income is $7,800 (60 @ $130) and the gross profit is $1,875. The stock of finished goods is $3,950 (40 @ $98.75). The stock of raw materials is the cost of 500 kgs of steel that has been purchased but remains unused at its purchase cost of $12/kg, a value of $6,000. Job costing and work in progress for services Whilst inventory may be thought of as only relating to manufacturers and retailers, it also relates to professional service firms. Accountants and lawyers are examples of firms with large work in progress inventories covering work carried out on behalf of clients but not yet invoiced. PLC Accountants have been conducting ABC Limited’s audit. At month end 15 partner hours and 60 audit hours have been allocated to ABC’s work, which has not been invoiced. The hourly cost rates used by PLC are $200/hour for partners and $80/hour for managers. Calculate the work in progress for PLC at month end. Work in progress: 15 partner hours @ $200 60 audit hours @ $80 Total $3,000 4,800 $7,800 Page 8 Process costing illustration Voxic Ltd manufactures lubricants. It does so in a continuous production process 24 hours per day, 7 days per week. During the course of a month, raw materials costing $140,000 were purchased and 100,000 litres of lubricant were produced. Materials issued to production cost $75,000 and conversion costs incurred were $55,000. 80,000 litres of lubricant were sold for $1.50/litre. At the end of month, calculate: The unit cost of production The gross profit The value of inventory. The cost of production for the month was $130,000 (materials $75,000 + conversion $55,000). As 100,000 litres were produced, the cost per litre is $1.30 ($130,000/100,000 litres). The cost of sales for the 80,000 litres sold was $104,000 (80,000 @ $1.30). Sales proceeds were $120,000 (80,000 @ $1.50) and gross profit was $16,000. Finished goods inventory is $26,000 (20,000 litres unsold @ $1.30). Raw materials inventory is valued at $65,000 ($140,000 purchased less $75,000 issued). Process costing with partially completed units – weighted average method Kazoo produced oils on a process basis during a month. The opening work in progress was 7,000 units, consisting of materials $12,000 and conversion costs $30,000. 12,000 units commenced production during the month. The closing work in progress was 4,000 units, 75% complete. The cost of materials issued to production during the month was $140,000. The conversion costs for production during the month were $80,000. Calculate: The number of units completed The equivalent units in WIP The cost per unit, using the weighted average method The cost of work in progress and finished goods at month end. Note: In process costing examples, unless you are advised otherwise, materials are assumed to be added at the beginning of the process, and conversion costs are added uniformly throughout the process. Page 9 Opening WIP Units commenced Closing WIP Completed Units 7,000 12,000 19,000 4,000 15,000 Cost per unit: Opening WIP $ Material Conversion Total 12,000 30,000 $42,000 Cost for month $ 140,000 80,000 Total $ 152,000 110,000 $262,000 Completed units WIP Equivalent units Total equivalent units Cost per equivalent unit1 $ 15,000 15,000 4,000 3,0002 19,000 18,000 $8.00 $6.11 $14.11 Work in progress: Materials 4,000 @ $8 $32,000 Conversion 3,000 @ $6.111 $18,333 $50,333 Finished goods: 15,000 units @ $14.111 Total costs $211,666 $262,000 Note: If a FIFO method of costing and inventory valuation is used, a variation to this calculation is necessary. However, the FIFO method will not be examined in AFX9550 for process costing with partially completed units. 1 2 Total cost divided by total equivalent units 4,000 units, 75% complete at end of month = 3,000 equivalent units Page 10 Long term contract costing Long term contract costing is a method of job costing that applies to large units that are produced over a long period of time, e.g. construction projects. Because of the length of time the contract takes to complete, it is necessary to apportion the profit over several accounting periods. Although the goods that are the subject of the contract have not been delivered, AASB111 Construction Contracts requires that revenue and costs be allocated over the period in which the contract takes place (e.g. the construction period). The stage of completion method is the most common method to be applied to long term contracts. Under this method, profit recognised is the proportion of work carried out, taking into account any known inequalities at the various stages of the contract. The costs incurred in reaching the relevant stage of completion are then matched with income. However, where the outcome of a contract is not known with reasonable certainty, no profit should be reflected, although losses should be recognised as soon as they are foreseen. Long term contracts will frequently allow for progress payments to be made by a customer at various stages of completion. For construction contracts, there will typically be an architect’s certificate to support the stage of completion. Contracts may also include a retention value, a proportion of the total contract price that is retained by the customer and not paid until a specified period after the end of the contract. Macro Builders has entered into a 2 year contract to construct a building. The contract price is $1.2 million, with an expected cost of construction of $1 million. After 1 year, the following costs have been incurred: Material delivered to site $500,000 Salaries and wages paid 130,000 Overhead costs 170,000 The architect certifies the value of work completed to the contractual stage for a progress payment as $600,000. Macro estimates that it will cost $250,000 to complete the contract over and above the costs already incurred. Calculate: The anticipated profit on the contract The amount of profit that can be considered to have been earned to date. Page 11 Costs of construction: Material delivered to site Salaries and wages paid Overhead costs Less work not certified Cost of work certified Anticipated profit: Cost of work certified Work not certified Estimated cost to complete Contract price Anticipated profit $500,000 130,000 170,000 $800,000 200,000 $600,000 $600,000 200,000 250,000 1,050,000 1,200,000 $150,000 Expected cost of construction $1,000,000 (or $1,050,000) Percentage complete 60% ($600,000/$1,000,000) Take up profit of 60% of $150,000 = $90,000 Management accounting statements The collection and analysis of financial data on manufacturing activities, adjusted by the valuations of inventory for raw materials, work in progress and finished goods, results in a manufacturing statement and cost of goods sold statement produced for management accounting purposes. Manufacturing statement Direct material: Raw material inventory at beginning of period Purchases of raw materials Raw material available for use Less raw material inventory at end of period Raw material usage in production Direct labour Manufacturing overhead: Factory rental Depreciation of plant & equipment Light & power Salaries & wages of indirect labour Total manufacturing costs Add work in progress inventory at beginning of period Less work in progress inventory at end of period Cost of goods manufactured Page 12 50,000 150,000 200,000 40,000 160,000 330,000 50,000 30,000 10,000 60,000 150,000 640,000 100,000 740,000 60,000 680,000 Cost of goods sold statement Finished goods inventory at beginning of period Cost of goods manufactured Goods available for sale Less finished goods inventory at end of period Cost of goods sold Income statement Sales Less cost of goods sold Gross profit Less selling and administrative expenses Net profit 160,000 680,000 840,000 120,000 720,000 1,000,000 720,000 280,000 150,000 130,000 Included in the Notes to the Accounts would be a breakdown of the valuation of inventory in the current assets section of the Balance Sheet. This would show: Inventory raw materials Inventory work in progress Inventory finished goods Total 40,000 60,000 120,000 220,000 Concluding comments It is essential to value inventory for financial reporting purposes. However, as chapters 10, 11 & 12 have shown, inventory costs may not be suitable for decision making purposes. The assumptions and limitations of costs based on accounting standards have to be understood and questioned in terms of their relevance for day to day decision making. Page 13