Block III

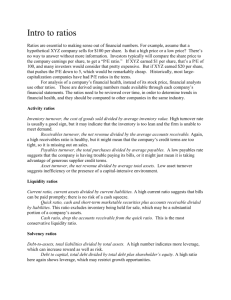

advertisement