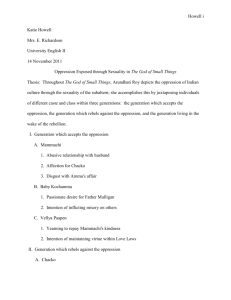

The Creative Use of Language in The God of Small Things

advertisement

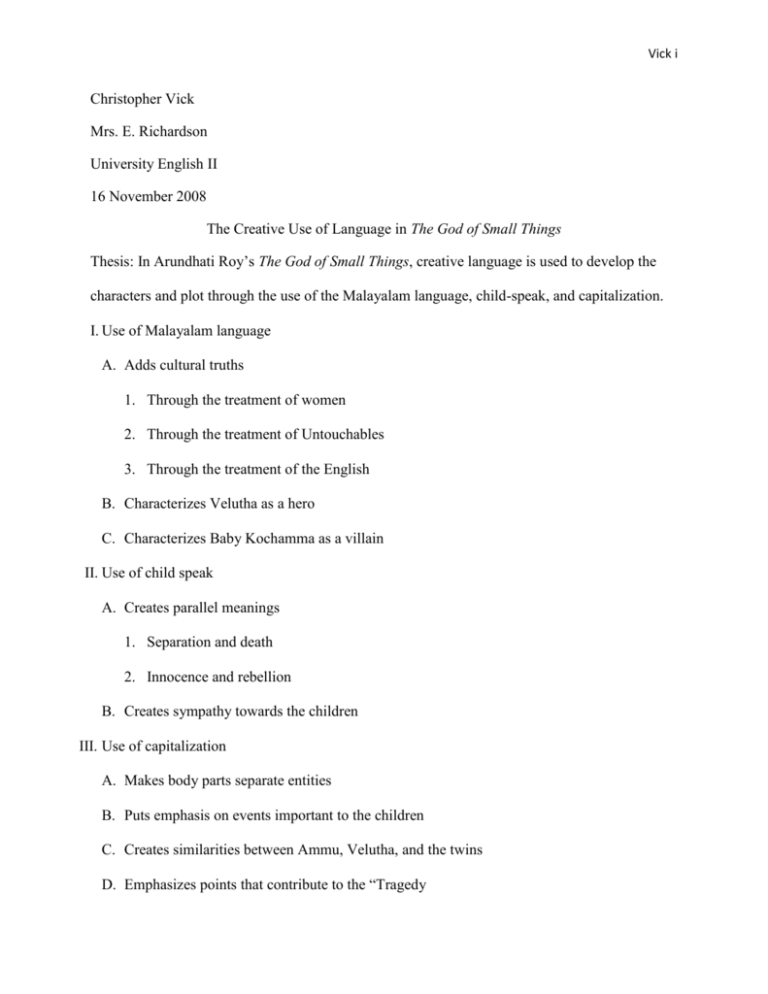

Vick i Christopher Vick Mrs. E. Richardson University English II 16 November 2008 The Creative Use of Language in The God of Small Things Thesis: In Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things, creative language is used to develop the characters and plot through the use of the Malayalam language, child-speak, and capitalization. I. Use of Malayalam language A. Adds cultural truths 1. Through the treatment of women 2. Through the treatment of Untouchables 3. Through the treatment of the English B. Characterizes Velutha as a hero C. Characterizes Baby Kochamma as a villain II. Use of child speak A. Creates parallel meanings 1. Separation and death 2. Innocence and rebellion B. Creates sympathy towards the children III. Use of capitalization A. Makes body parts separate entities B. Puts emphasis on events important to the children C. Creates similarities between Ammu, Velutha, and the twins D. Emphasizes points that contribute to the “Tragedy Vick 1 Christopher Vick Mrs. E. Richardson University English II 14 November 2008 Creative Use of Language in The God of Small Things Arundhati Roy’s novel The God of Small Things, a Booker Prize winner, centers around the tragic events that unfold over the course of just a few days in fictional Kerala, Ayemenem, India. It explores the depths of how a combination of small events can build up and affect people’s personalities and lives in drastic ways. The story revolves around a set of fraternal twins, Estha and Rahel, and their immediate family: Ammu, Chacko, Pappachi, Mammachi, Baby Kochamma, Margaret Kochamma, Sophie Mol, and Velutha. The plot moves multiple times from the present, where Estha and Rahel are meeting for the first time in twenty-odd years, to the past, to recount a “Tragedy” that occurred. This “Tragedy” comes into full effect when a series of completely disconnected, yet unfortunate, events come together. These events result in Sophie Mol’s drowning, Velutha’s brutal murder at the hands of the police, Estha’s deportation, and Ammu’s disgrace. In the midst of these happenings, Roy employs clever use of creative language to characterize the family and show the reader how their personalities contribute to the “Tragedy.” In The God of Small Things, creative language is used to develop the characters and plot through the Malayalam language, the use of capitalization, and child-speak. Firstly, the Malayalam language is used to develop certain characters and aspects of their lives. The language is mainly used by the more traditional and older Indian family members: Pappachi, Mammachi, Baby Kochamma, and the lower class. Its use also helps lay the foundation for the treatment of the weak: women, children, and lower caste members. Its uses Vick 2 not only show the differences in education, but in how the Indians would glorify English, both the language and the people. In the case of Baby Kochamma, however, the differences in the language and culture fuel her rage against Ammu and Velutha. Because the Indians thought much more highly of the English than themselves, many of them feel that using the English language will help give them some sort of superiority. Pappachi, Ammu’s father, Rahel and Estha’s grandfather, dies before the time of the novel. However, Ammu makes several references back to him, of how cruel he was, and of his idolizing of the English. For example, when Ammu divorced her husband, she told Pappachi it was because he was trying to whore her out for money. Pappachi “would not believe her story – not because he thought well of her husband, but simply because he didn’t believe that an Englishman, any Englishman, would covet another man’s wife” (Roy 42). This shows how Pappachi idolized the English, and would hear nothing bad about them, even if it concerned his own daughter. He was also extremely strict as a husband. When Mammachi first began lessons on the violin, they “were abruptly discontinued when Mammachi’s teacher . . . made the mistake of telling Pappachi that his wife was exceptionally talented and in his opinion, concert class” (49). Again, this shows his cruelty as a husband, not allowing his wife any sort of fame or skill that would set her above him. Baby Kochamma’s references to Malayalam are the causes for her hatred toward Ammu and Velutha. When the family is on their way to Cochin to see The Sound of Music and to pick up Margaret Kochamma and Sophie Mol, they have to go through a communist march. There, Rahel sees Velutha. When the marchers get to their car, they open it and harass Baby Kochamma. They tell her to “say ‘Inquilab Zindabad!’ ‘Inquilab Zindabad,’ Baby Kochamma whispered. ‘Good girl.’ The crowd roared with laughter” (77). Uttering the phrase, which means Vick 3 ‘Long Live the Revolution,’ completely humiliates Baby Kochamma in front of all the marchers. It is stated that “Baby Kochamma focused all her fury at her public humiliation on Velutha . . . She began to hate him” (78). Because she tries to be highly dignified, being embarrassed greatly angers her. Because Rahel sees Velutha in the crowd and announces it, she turns all her rage against the marchers toward Velutha, in a way to somehow get revenge against all of them. The twins often speak in both languages, both for fun and because they are instructed to. When preparing for Sophie Mol, the twins are made to speak in English so the family seems more educated. Baby Kochamma “eavesdropped relentlessly on the twins’ private conversations, and whenever she caught them speaking in Malayalam, she levied a small fine” (36). Baby Kochamma feels it important to appear impressive to the English. However, when they were younger, they had “asked what cuff-links were for—‘To link cuffs together,’ Ammu told them” (50). This simple logic thrilled the twins, and it “gave them an inordinate (if exaggerated) satisfaction, and a real affection for the English language” (50). This shows that the twins genuinely enjoy the English language, and do not speak it to seem impressive, as Baby Kochamma and Pappachi do. The Malayalam language is most often used by the Untouchables and communist party members. When Rahel accuses Velutha of lying about being a communist because of his smile, he replies, “‘That’s only in English! . . . In Malayalam my teacher always said that ‘Smiling means it wasn’t me’” (169). While this shows that Velutha is playful towards the children, another look will show the relevance of it towards the caste system in India. Rahel and Estha were given an English education, while Velutha, an Untouchable, was taught in Malayalam. The various workers who work in Mammachi’s Paradise Pickles factory also speak mostly in Malayalam, as well as the dominating Communist party. Vick 4 Kochu Maria, the maid of Mammachi’s house, also speaks only in Malayalam, and often is confused when the children speak English to her. After Ammu reads Julius Caesar to Estha and Rahel, Estha would reenact the scene before Kochu Maria. She “was sure that Et tu was an obscenity in English and was waiting for a suitable opportunity to complain about Estha to Mammachi” (80). Because of her ignorance, she misinterprets all English said to her, and immediately thinks that it is an insult. It is because she is uneducated in the language that she does this, and it shows how she is an insecure, defensive person. “Velutha” means ‘white’ in Malayalam, which contrasts his dark complexion. The theme of whiteness in the novel is one of “privilege and exclusion . . . activated by the coming of the white/blond child Sophie Mol into the brown world of India and the black world of its Untouchables” (Dooley screen 4) This is further shown when Rahel sees Velutha in the crowd of communists. She states she sees “Velutha marching with a red flag. In a white shirt and mundu with angry veins in his neck. He never usually wore a shirt” (68). This white shirt he does not usually wear symbolizes his uniqueness as an Untouchable. Because of the meaning of his name, and what whiteness in the novel stands for, Velutha is seen as a major character towards the good, and acts against the evils of the caste system. Twinkle B. Manavar states “in Roy's novel The God of Small Things, the 'God' is definitely Velutha, who can perhaps be called the hero of the novel” (screen 2). The meaning of his name in Malayalam is meant to show the purity and disgust with society that lies in Velutha, despite his extremely dark skin. His wearing of the white shirt shows his belief that the Marxist communists will make things better for the Untouchables. Another creative language use is child-speak. Because the story is told mostly from the twins’ perspectives, particularly Rahel’s, many words and actions are altered in their views. They Vick 5 split words into syllables, read backwards, create rhymes and songs, and use logic that would make no sense to anyone but a child. Yet some also create an underlying, dark meaning that can also be interpreted. A repeated phrase throughout the novel is one that states Ammu and the grown twins’ ages as “not old. Not young. But a viable, die-able age” (5). Rahel repeatedly thinks this twisted rhyme to refer to the potential their age, thirty-one, has, yet also how fragile it can be, in the case of Ammu, and how easily things can change. Another phrase with dark undertones is how the children split the word “divorce” into “die-vorce” (124). This symbolizes how fatal divorce in the Indian culture could be, because once a woman divorces, they are supposed to remain sexually chaste for the rest of their lives. Its dark, underlying meaning also becomes evident when Ammu breaks this rule of society by having an affair with Velutha, which ends in Velutha’s death. “Later” also becomes “Lay. Ter” to emphasize the syllables, and to show the children’s reluctance for “later,” which is always the time they are told they will be punished (139). During uncomfortable situations, the children will refer to themselves by nicknames they’ve made up, and will recite rhymes and songs in their head. A clear example is when Velutha is beaten by the police. The children think of themselves as “Mrs. Eapen and Mrs. Rajagopalan, Twin Ambassadors of God-knows what,” which are characters they pretended to be earlier with Velutha (293). They also chant a little poem in their heads: “Blood barely shows on a Black Man.(Dum dum) It smells though, Sicksweet. Like old roses on a breeze. (Dum dum)” (293). The children do this to detach themselves from the experience, so it seems more like pretending than real life. They do not want to face the fact that a man they loved has been killed in front of them, so they fall back into this childish world. The same thing happens when the Vick 6 children lie and say Velutha kidnapped them. Estha thinks “Little Man. He lived in a cara-van. Dum dum” and refers to himself as “Ambassador E. Pelvis. With saucer-eyes and a spoiled puff. A short ambassador . . . on a terrible mission . . .” (303). Estha does not want to scapegoat Velutha, but Baby Kochamma has informed him that if he doesn’t, all of them will go to jail. Not all uses of the child-speak have darker meanings, however. Many of their uses show simple childish ignorance or playfulness. The children will often read words backwards for fun, which is something they’re often chided for doing. When they insult a friend of Baby Kochamma’s, the woman tells her “that she had seen Satan in their eyes. nataS ni rieht seye” (58). Their habit of reading backwards shows that the children ignore much of what the adults around them say, because they do not view it as important in their views. They are also ignorant of certain spellings. When Ammu calls in Rahel for her afternoon nap, her “heart sank. Afternoon Gnap. She hated those” (174). Because of their delight in the English language, and their discovery of silent letters, the children will stick in silent letters in unusual places. They will also run words together, referring to an owl as “a Nowl,” and the sentence “Hello, all” as “Hello wall” (185; 136). These simple, silly mistakes that the children make in pronunciation and spelling are meant to create sympathy towards them. They are used to show the children’s ignorance of not only language, but of the world around them, because they are so young. And that they should take no blame for the “Tragedy” that occurs, even though parts of it are their fault. A final creative language device is the use of capitalization. Throughout the novel, Roy uses unique capitalization as a device to emphasize special events, particularly ones that lead up to the “Tragedy.” With it, objects become “Objects,” events become “Events,” and deeper meanings are created. These capitalizations often show people’s reactions to the objects and Vick 7 events, particularly the children’s, Ammu’s, and Velutha’s. Because the story is seen mostly through Rahel’s adolescent eyes, the uses often show events that are important to the children, and not necessarily to the adults. The “Events” that are emphasized also show the important steps in the plot that eventually lead to the climax. From the beginning of the novel, a “Tragedy” is referenced to repeatedly. It quickly comes to the attention of the reader that this tragedy is in fact “The Loss of Sophie Mol” (17). The phrase is capitalized to show the reader the importance of the event. Even though it appears in the very beginning of the novel, the “Loss” is referred to by future Rahel repeatedly to emphasize the point that it is an important “Event.” The uses also show the small events that are important to the children, but not the adults. When the family is using the restrooms, Estha had to go into the men’s room by himself. He thinks: “To piss in the pot would be Defeat. To piss in the urinal, he was too short. He needed Height” (92). The capitalization of the words “defeat” and “height” simply show small moments of importance to Estha. He wants to be able to use the urinal himself, and to not would be admitting “Defeat.” To do it he needed something extra, which is “Height.” Because the story is seen through Rahel’s eyes, and the capitalizations refer mostly to the children’s views, it’s important to note when the adults use the unique capitalization. When an adult does use it, it shows how that person identifies with the children. The two adults that use it the most are Ammu and Velutha, because they share a weakness with the kids: they have almost no rights in the Indian society. The children are weak because of their youth, Ammu because she is a woman, and Velutha because he is an Untouchable. These four characters are also regarded as the four major heroes of the novel. The capitalizations used link them together. Vick 8 When the family, with Margaret Kochamma and Sophie Mol, return home, “Rahel looked around her and saw that she was in a Play. But she had only a small part” (164). The adults around her are all acting; they’re pretending to be a perfect family in front of Margaret and Sophie. Rahel knows they’re acting, perhaps because she is a child and doesn’t act herself. She also regrets her small part in the play, because she is a child and is used to the attention she regularly receives. She develops a jealous tendency towards Sophie Mol, the main actress in the “Play.” Interestingly, Ammu also decides to not act. The cook begins sniffing Sophie Mol’s hands, to which Chacko explains that it’s her way of kissing. Margaret then asks “do the Men and Women do it to each other too?” to which Ammu sarcastically replies, “that’s how we make babies” (170). This is one of the few times the unique capitalization is used without any context towards the children. It shows Ammu’s reluctance to be a part of the cold, fake, upper-class of India, due to the abuse she experienced living with Pappachi. It is said “she did exactly nothing to avoid quarrels and confrontations. In fact, it could be argued that she sought them out, perhaps even enjoyed them” (173). Velutha also uses the unique capitalization when speaking to Rahel. When she makes the statement that they aren’t “Playing,” he replies “that is Exactly Right. . .we’re not even Playing” (173). Velutha is the other adult character who periodically uses the capitalization. His use of them shows that he, as a Communist Untouchable working for the factory Union, and the God of Small Things himself, identifies with the innocent children, and that he can partially see the world as they do: innocent and yet cruel, big and yet small, and full of potential for both life and death. Another important part of what the capitalization of the words does is that it helps create the characters while also furthering the plot by emphasizing the Events that lead up to the “Death of Sophie Mol” and subsequent actions. When the family is on their way to pick up Sophie Mol Vick 9 from the airport, they leave a day early to catch a screening of The Sound of Music. There, Estha meets a drink vendor, who he calls the Orangedrink Lemondrink Man. When Estha is molested by the Orangedrink Lemondrink Man, the hand he is forced to use becomes a capitalized entity. The scene directly following says: “He held his sticky Other Hand away from his body. It wasn’t supposed to touch anything” (100). Throughout the rest of the book, the hand is always referred to as his “Other Hand.” As a child, Estha is unaware of how to respond to the situation; however, he is aware that what he did is shameful. He repeatedly makes references to Sophie Mol, growing jealous that she never “ever held strangers’ soo-soos” (101). The capitalization of his “Other Hand” shows Estha’s need to separate the guilty body part from himself, to disassociate the bad from him because he believes it will, in turn, make him a bad person. Chris Fox explains that the event traumatizes Estha because of “the betrayal of the child's trust in the adult and the treachery of, in this case, Estha's own painfully learned social politeness . . . functions to make him unwillingly complicit” (screen 3). The situation is made even worse when the man flirts with Ammu, and he reveals that he knows where they live. Because of what happened with the Orangedrink Lemondrink Man, Estha decides that “it’s Best to be Prepared…because Anything can Happen to Anyone” (Roy 189). The uses of these capitalizations show Estha’s paranoia that the Orangedrink Lemondrink Man will return for him. He and Rahel locate an old boat by the river and, with Velutha’s help, repair it. They then begin stealing food, clothing, and toys from the house and storing it in the boat, to be “Prepared” in case “Anything Happens.” The children’s preparation is one of the actions that contributes to the “Tragedy.” After Ammu is locked in a room because Mammachi discovers her affair with Velutha, she yells at the children in her grief and blind anger to leave her. Estha then decides “that though it was dark and Vick 10 raining, the Time Had Come for them to run away, because Ammu didn’t want them anymore” (250). And, because of what the Orangedrink Lemondrink Man did, they were ready. As the scene unfolds, with the flipping of the boat as the three children attempt to cross the river, it becomes obvious that the “Time that Had Come” is, in fact, the “Loss of Sophie Mol.” The capitalizations of these two phrases show the climax of the story. However, as Scott Trudell points out, “Sophie Mol’s actual drowning is an accident, an understated tragedy in which she simply vanishes in the river” (screen 1). It becomes aware that, at the time, the actual “Loss of Sophie Mol” that has been mentioned since the beginning of the book is merely a passing moment. It is the results of the “Loss” that are the real “Tragedy.” The “Loss of Sophie Mol” is not the only result of Estha and the Orangedrink Lemondrink Man’s actions. In fact, her death leads to more chaotic, darker results. The house that Rahel and Estha take refuge in, called the History House, is also the place Ammu goes to have her affair with Velutha. Unknown to the children, Velutha hides in the house as well, waiting for Ammu, because he doesn’t know she has been locked up. Baby Kochamma, with her rage against Velutha, lies to the police in an effort to save the family’s reputation. She says “he had tried to. . .to force himself on her niece,” and that he kidnapped the children and killed one (245). The police then went to the History House, sneaked in, and beat Velutha senseless. They then examined “their Work, abandoned by God and History, by Marx, by Man, by Woman and (in the hours to come) by Children, lay folded on the floor” (294). This quotation, and its capitalizations, show how the Untouchable Velutha is abandoned by God, his fellow men and women, and the children in his time of most need. The police realize that Velutha had not kidnapped the children, because of the toys and food they had with them. So they hide the Vick 11 evidence, and Baby Kochamma convinces the children to lie and say that Velutha had kidnapped them. So, in the end, not even “History” itself would know what really happened to Velutha. Another result of the “Tragedy” and another use of capitalization is Estha being “Returned.” After Sophie Mol’s funeral, “Estha was Returned. Ammu was made to send him back to their father” (10). This deporting of Estha back to his father is the final capitalized “Event” of the book. It is said that, in both of them: “Childhood tiptoed out. Silence slid in like a bolt. Someone switched off the light and Velutha disappeared” (303). It is the final point of the twin’s childhood, the last time they are together until they reunite when they are thirty-one. It is the final “Event” that makes Estha become mute, and Rahel become quiet, which were their ways of coping. It is in this moment that the final punishments are given: Velutha is dead, Ammu has been cast out from society, and the children are separated. The God of Small Things explores the depths of human love, and hatred. The language employed develops the characters beautifully: compassion, hatred, fear, sympathy, disgust, and love are all felt through the words. The use of the Malayalam language helps create the stark contrast of cultures, and how much the Indian culture is being replaced with the English, but not necessarily for the better. The unique use of capitalization helps characterize the children and their innocence, but also to show the reader the important Events that lead up to the “Tragedy.” Child-speak helps to further show the children’s views toward the Events and other characters, and also creates important foreshadowing. The God of Small Things is a novel that shows the world how a single person or a single action can completely change the lives of many. The novel underscores how the big things can add and pile up to overwhelm humans, and blind them, but that it’s in the small things where God truly lies. Vick 12 Works Cited Dooley, Deborah A. “Literary Contexts in Novels: Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things.” Literary Contexts in Novels: Arundhati Roy’s ‘The God of Small Things’ (2007): 1. Literary Reference Center. EBSCOhost. Mississippi U for Women Lib., Columbus, MS. 22 Sep. 2008 <http://search.ebsohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lfh&AN=27264907&site=ehostlive>. Fox, Chris L. “A Martyrology of the Abject: Witnessing and Trauma in Arundhati Roy's The God of Small Things.(Critical Essay).” Ariel. July-Oct. 33.3-4 (2002): 35. Literature Resource Center. EBSCOhost. Mississippi U for Women Lib. Columbus, MS. 12 Nov. 2008 <http://galenet.galegroup.com.libprxy.muw.edu/servlet/LitRC?&srchtp=adv&c=1&ste=7 8&stab=2048&tbst=asrch&tab=2&ADVST1=RN&bConts=2050&ADVSF1=A13665394 3&docNum=A136653943&locID=mag_u_muw>. Manavar, Twinkle B. “Velutha: The Downtrodden in Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things.” The Critical Studies of Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things (1999): 12429. Literature Resource Center. EBSCOhost. Mississippi U for Women Lib. Columbus, MS. 12 Nov. 2008 <http://galenet.galegroup.com.libprxy.muw.edu/servlet/LitRC?vrsn=3&oldim=1&locID= mag_u_muw&ste=135&docNum=H1100067253>. Roy, Arundhati. The God of Small Things. New York: Harper, 1998. Trudell, Scott. “Critical Essay on The God of Small Things.” Novels for Students 22 (2006). Literature Resource Center. EBSCOhost. Mississippi U for Women Lib., Columbus, MS. Vick 13 23 Sept. 2008 <http://galenet.galegroup.com.libprxy.muw.edu/servlet/LitRC?vrsn=3&oldim=1&locID= mag_u_muw&ste=135&docNum=H1420067561>.