Key concepts in anthropology: ethnocentrism and

advertisement

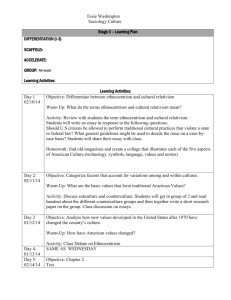

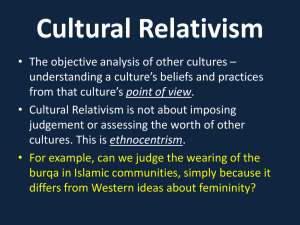

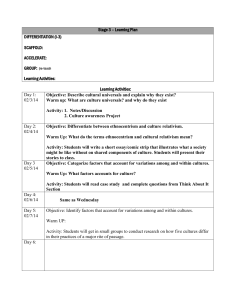

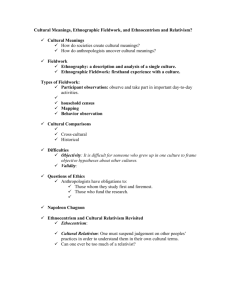

Key concepts in anthropology: ethnocentrism and cultural relativism The primary way that anthropologists gather information is to spend time with the people they want to better understand. They do what is called participant observation fieldwork, spending time with a group of people and living with them for a year or more. Anthropologists work to understand people’s lives from the perspective of the people with whom they are living. In order to better understand people in culture groups, anthropologists work hard to be aware of their own prejudices and assumptions. The more the anthropological researcher judges a group based on the researcher's own cultural beliefs, the less likely the anthropologist will be able to see a whole and accurate picture of the group she/he is observing. As such, there are two ideological concepts that are part of the foundation of cultural anthropology. Ethnocentrism: judging another culture solely by the values and standards of one’s own culture. Ethnocentrism is the belief that one’s own culture (religion, ways of doing things, beliefs, economic system, political system, etc. etc.) is superior. All people, to some extent, are ethnocentric. They have to be in order to get along with other people in their groups. Humans are group animals. They cannot survive without other people. As such, they need to cooperate with each other. “We can’t carry on without that sense of conviction and commitment” (Karp 2001: 25). If we did not believe in the rules and philosophies of our own groups, social cohesion would be difficult. Ethnocentrism, then, is about survival. Our culture provides the ‘filters’ by which we see the world (Raybeck 1996: 2). Through those filters characteristics of other cultures can be particularly upsetting to Americans. For example: - most U.S. students are horrified by cruelty to animals - we feel most societies don’t treat women well enough - we are strict about being on time - we look to the future so we can’t understand why other people feel cursed or constrained by their history. - we talk straightforwardly when we criticize or say no, so we think people in other cultures ‘beat around the bush’. - we value the individual over the group. - we are afraid of germs When we encounter other people who do not believe or behave according to our assumptions, we become frustrated. Ethnocentrism is normal, but also dangerous. 1 Extremes of ethnocentrism are destructive and ugly. They include racism, war, genocide, culturecide, etc. etc. World War II and its atrocities were about ethnocentrism. Darfur is about ethnocentrism. The Rwandan Genocide in 1994, when the Hutus participated in mass killing of an estimated 800,000 Tutsis and pro-peace Hutus, was about ethnocentrism. The Euro-American taking of land from and killing of thousands of Native Americans was about ethnocentrism. The Iraq war is about ethnocentrism. Extreme ethnocentrism leads to hatred, Nazi death camps, the Trail of Tears (removal of the Cherokee from Tennessee and Georgia to Oklahoma). If you see your own culture as superior, you are then able to see other people as less than yourself, or wrong, and to justify negative behavior toward them. A good anthropologist puts her/his sense of ethnocentrism on hold, working to understand people through a sense of cultural relativism. Cultural relativism is the understanding that a group’s knowledge, social systems, beliefs and ways of doing things are relative to that group’s environment, history, and circumstances. To comprehend one aspect of a culture group is to realize that it is part of a whole and cannot be understood without knowing more about that whole. Remember, culture is integrated and each cultural characteristic or practice is connected with other facets of culture. Anthropologists realize that every culture has a logic that makes sense to its own members. For the sake of scientific accuracy, anthropologists must suspend judgment in order to understand the logic and dynamics of other cultures. Anthropologists are not usually moral relativists and are not required to approve of all cultural practices. However, it is possible to understand another culture’s practices without approving of them. Most anthropologists draw the line between relativism and judgment at human rights. But everyone has their own beliefs about human rights, and forcing our version of ‘human rights’ on another group can sometimes be quite complex and even destructive. The moderate doctrine of cultural relativism: - avoid ethnocentrism - judge or analyze a group only in the context of their own history and culture, not yours. 2 - avoid comparing cultures to each other. You can’t demonstrate that “people in Japan are more polite than people in Hong Kong” because politeness is not comparable between the two cultures. Each has its own kind of politeness (Omohundro 2008:359). Extreme relativism can be problematic, just as extreme ethnocentrism is problematic. Extreme relativism involves taking the view that there are no universals by which to judge our own or another culture. It is like saying there are no rights or wrongs or no moral benchmarks outside of culture by which to judge. The extreme of this way of thinking is a kind of moral anarchy. In truth, “we require some ethical foundation in order to say, for example, that genocide (“ethnic cleansing”) is bad, that torture is bad, and so on” (Omohundro 2008: 359). Extreme cultural relativism would be to say that we cannot judge what happened in Nazi Germany or Rwanda because “it was just their culture”. Anthropologists generally understand that: 1) Ethnocentrism and racism are wrong. 2) Cultural, linguistic, religious, and other kinds of diversity are good. 3) Societies and ethnic groups have the right of self-determination, of ownership of their cultural heritage and property, and of instruction of their own children. 4) Anthropology should work to increase public understanding of culture in general and public knowledge and appreciation of other cultures in particular. 5) All humans share a common humanity. Omohundro, John 2008. Thinking Like an Anthropologist. Boston:McGraw Hill. 3